-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Mighty Mumbai: Urbs Primus in Indus

Mar 6, 2015

by

Amber N. Wiley, 2013 Brooks Travelling Fellow

Palimpsest. Microcosm. Hybrid. Pluralist. Diasporic. Cosmopolitan. Third world. Postindustrial. Postcolonial. Post-Independence. Global. Hypermodern. Slum. Polynuclear. Agglomeration. (Con)fusion. Bombay. Mumbai.

“Mombay.” I kept typing it. “Mombay.” When I was looking for articles on Mumbai and had little luck typing “Mumbai” I decided to search instead for “Bombay.” The city only officially changed its name in 1996 after the Hindu nationalist party Shiv Sena won elections in the state of Maharashtra. Literary scholar Rashmi Varma characterizes this act as “provincializing the global city.”1 Much of the literature I read discussed architectural and urban trends in “Bombay.” Somewhere along the way, however, “Mombay” was all my brain could manage. Bollywood, a nickname for the Indian film industry, is a portmanteau of the words “Bombay” and “Hollywood.” Bollywood is still Bollywood almost twenty years after the city name changed. Most Indians I spoke to still referred to Mumbai as Bombay. I came across the keywords above in the literature on the city, and my research on Mumbai has led me to understand the city as all these things, but not just any one of these things.2 Most scholars I have consulted agree – more research must be undertaken to understand and analyze the city on its own terms. In many ways, the city I experienced was indeed “Mombay:” the hybrid provincial capital of Maharashtra and the global millennial city.

Figure 1. Null Bazaar in Bhuleshwar neighborhood of Mumbai.

Roots of Mumbai

The human occupation of the area we know as Mumbai dates back to prehistory. The region that forms metropolitan Mumbai was originally an archipelago of seven islands with fishing villages settled by the indigenous Koli. The patron goddess of the Koli fishermen was Mumba Devi. It is from this goddess that the city derives its current name. The area was successively ruled by separate Buddhist, Hindu, and Muslim kingdoms until the Portuguese gained control in 1534. The architectural heritage from these various political and religious entities includes the Buddhist Kanheri and Mahakali caves, the Buddhist and Hindu Jogeshwari Caves, the Hindu Walkeshwar Temple, the Buddhist and Hindu Elephanta Caves, and Portuguese forts and churches. The name Bombay is a derivation of Bombaim, or “Good Bay,” the Portuguese name for the settlement.

Figure 2. Mumba Devi Temple in Bhuleshwar.

Most of my reading, however, focused on the time period after Portuguese rule. Many architectural histories began with the Portuguese handing over Bombay as part of the wedding dowry for Catherine de Braganza to Charles II of England in 1661. The English East India Company leased the islands from 1668 until 1757 when the company took over rule in the region. The East India Company continued to expand into the subcontinent and gain further autonomy until the Indian Rebellion of 1857. From 1858 to 1947 Bombay was under control of the British Raj.

On Hybridity and Pluralism

After writing my preceding entry on Harar and Goa I realized “hybridity” might not be the word I needed to describe the conditions I experienced in both regions. “Pluralist” is. This is an important distinction, not just given over to semantics, because it helps encapsulate the architectural variety. There were aspects of various cultures that remained distinct and clearly identifiable as belonging different architectural traditions. Catholic churches of Goa. Egyptian mosque in Harar. Indian merchant houses in Harar. Portuguese villas in Goa. Italian municipal buildings in Harar. These carry the ambitions and messages of each cultural entity in architectural program, form, and function. Hybridity can only truly be found in the small decorative details – the woodwork in Goa, for instance, or the use of a certain color palette in Harar.

Architectural pluralism is also central to the understanding of the urban fabric of Mumbai. This is a direct result of the city’s position as a “factory” in the English East India Company. The Company sought to bring merchants, traders, and artisans of high standing from various castes and religions to the city, and therefore offered a freedom of cultural and religious tradition. This included Armenians, Hindu and Jain Banias, Muslim Bohras and Khojas, Jews, Parsis, and Gujaratis.3 The architecture of Mumbai reflects the cultural autonomy of these various groups.

Figure 3. David Sassoon Library (1870), Army and Navy Building (1890), and Watson’s Hotel (1869) in Kala Ghoda.

Sassoon was a Baghdadi Jew, businessman, and philanthropist responsible for funding many projects in Bombay, including the Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue. The expansive parking lot in front of this row of buildings is the former site of the statue of King Edward VII, the Prince of Wales (also financed by Sassoon). The statue was called “Kala Ghoda” or Black Horse. The neighborhood derived its name from the statue, which was removed to the Byculla Zoo.

Figure 4. Jain temple, Bhuleshwar.

Figure 5. Mosque, Bhuleshwar. This mosque has classical details, including double-height Corinthian-inspired pilasters along the main façade.

I walked extensively throughout South Mumbai: 4 the Fort area, Kala Ghoda, Colaba, and Bhuleshwar. The Fort area and Kala Ghoda immediately took me back to London. The scale and uniformity of the structures, the cool, reserved face of classicism in the Fort and the dark, expressive Victorian Gothic spires. These were mixed in with the major Indo-Saracenic monuments erected at the end of the nineteenth century, and the Art Deco structures of the interwar years. The street scale in Bhuleshwar was much more intimate than that of other areas of South Mumbai. Part of this is due to the fact that Bhuleshwar is located in the high-density area previously known as “native town. As architectural historian Preeti Chopra notes:

The British viewed the city in terms of color and settlement pattern. In their eyes the Indians lived in what the British called the "native town" or "black town," characterized by its high population density and intricate network of streets. The Europeans lived in the "European quarter" or beyond the bazaars in spacious, low-density suburbs. In contrast, the complex mapping of the city by Indians included religious buildings, water tanks, statues, markets, and other localities inhabited by Bombay's diverse populations.5

One can find deliberately hybrid architectural design in its truest form in Mumbai. British architects developed and popularized the Indo-Saracenic style in the late nineteenth century. George Wittet, a major proponent of the style, was the architect of the Prince of Wales Museum, now known as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, and the Gateway of India. Both structures were erected to commemorate King George V and Queen Mary’s visit to India in 1911.

Figure 6. Interior view of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (Prince of Wales Museum). The interior details of the central hall are inspired by architecture from across the country.

British architects who traveled to India to find work in the late 1800s and early 1900s frequently wrote about the state of architecture in India and the need to create something at once traditional and modern. Articles appeared in the Journal of the Society of Architects with titles like “Characteristic Architecture for India: A Plea for the Saracenic Form,” (1909), “Government Architecture in the East: Indian Architects for India,” (1911), “Architects’ Difficulties in India: The Need of Trained Men,” (1912), “Indian Architecture, and Its Suitability for Modern Requirements,” (1913). These called for the study of traditional Indian architecture, and the necessity for training of architects on the subcontinent (as opposed to England) to promote a new and eclectic style of modern Indian architecture. Architects Magazine, a short-lived British periodical, featured articles on ventilating buildings in India and highlighted outstanding building design, such as the Grant Road residence of Parsi industrialist Jamsetji Nusserwanji (J. N.) Tata.6

Parsi Patronage

Parsi patronage of the building arts is one of the most fundamental points to understand the architectural heritage of late nineteenth and twentieth century Bombay. I spent all of my first day in Mumbai being whisked around the city in a cab trying to get technical support for my Apple products. Several of the stores and service centers that had what I needed were in the major shopping area near the Royal Opera House. When I pulled up to the Royal Opera House I oohed and awed. My cab driver stated the Parsis constructed the building. I was confused, as I never heard the term before. In my mind I decided he meant “Farsis,” and instead of saying Persian he accidentally said the language of Persians. I quickly learned of the small, well-connected community of Parsis who had migrated to Bombay from the Gujarati region, where they had settled after escaping persecution in Iran for the religious practice of Zoroastrianism.7 Initially traders, this community penetrated many aspects of commercial and industrial enterprise, and had a favored position in the British trade hegemony.

Figure 7. Maneckji Seth Agiary (1733), second oldest surviving Parsi fire temple. Kala Ghoda neighborhood.

The Parsi community was active in architectural patronage in Bombay due to the success of various business ventures. One of the most important was the involvement of Parsi entrepreneurs in the cotton production and export industry in the nineteenth century. The American Civil War and port blockades on the exportation of cotton from the South forced England to increase its importation of cotton produced in India. This cotton boom created great wealth and opportunity to turn economic capital into cultural capital. Members of the Parsi business community were some of the greatest patrons of British architects practicing in Bombay. As historian Christopher W. London notes, “The Parsis were not the only benefactors to contribute to the 19th century architectural fabric of the city, but they helped set the tone and they established the precedent.”8

While London highlights Parsi involvement in building Victorian Bombay, architectural historian Michael Windover shows how Parsi architectural patronage continued in the interwar years. Windover examines patronage of Art Deco structures in general, and cinemas more specifically. While Mumbai is widely known for its amalgamation of Victorian Gothic, Indo-Saracenic, and Art Deco structures, particularly in the historic Fort Area, the Parsi connection to placemaking should be highlighted more. Perhaps it is not emphasized because the community has long been a minority population, and today it has considerably declined. When the nomination of the Victorian and Art Deco ensemble of Mumbai to the World Heritage List does not once mention the Parsi involvement in creating this varied and impressive heritage, something is amiss.

Figure 8. Regal Cinema (1933) financed by Parsi film exhibitor Pramji Sidhwa and designed by Charles Stevens, whose father Frederick William Stevens designed Victoria Terminus (Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) Station.

Curating the City

Mumbai has little in the way of heritage conservation of its industrial infrastructure. For a city that was built on trade and industry, this may seem surprising. Imagine Liverpool, Glasgow, Detroit, or Pittsburgh without an emphasis on their industrial heritage. It would be hard to truly understand the evolution of those cities. As architectural historian Jyoti Hosagrahar notes, the nineteenth century:

Saw the rise of a new and broad category of institutional buildings, including courthouses, museums, libraries, banks, city halls, elite boarding schools, colleges, and post offices. Railway terminals, factories, bungalows, and a network of dak bungalows (inspection rest houses) were other types of buildings that transformed the landscape of the South Asian subcontinent in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet these buildings of the modern age did not find historians until recently and many still await them.9

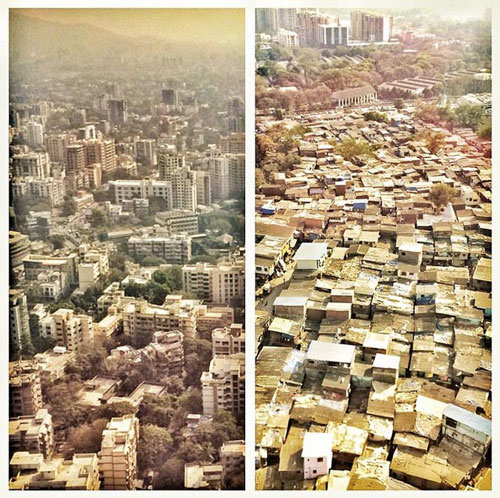

Perhaps this is because the areas in neighborhoods such as Girangaon and Parel surrounding former factories and cotton mills reveal the economic disparity that is modern Mumbai.10 It is at once the richest city in India, but more than half of its urban population lives in slums. These neighborhoods spread far beyond the boundaries of the Fort Area, upon which most of the architectural and heritage tourism is focused.

It is exceedingly important for historians to understand these economic conditions and disparities when making decisions about what and how to conserve. Mumbai in the millennium has moved beyond its colonial and industrial past, yet so much of the urban fabric in the historic core reveals these pasts to us.

Figure 9. Beyond South Mumbai the city continues to grow.

Bombay was the second most populous city in the British Empire after London. It was the “Urbs Primus in Indus.” As such historians have often tried to understand Mumbai in relation to both the history of British colonization and the rise of megacities in the Global South. Geographer Andrew Harris argues for new frameworks in understanding the city today, moving away from a Eurocentric approach to something more dynamic. He contends that we must:

Challenge conceptions of Mumbai as only a replicator or mimic of urbanisms fashioned elsewhere, whether in 19th-century Manchester or London or 21st-century Shanghai or Singapore. This involves greater acknowledgement of, and engagement with, Bombay’s specific socio-spatial formations of urban modernity and with the fundamental disjunctions into social experience and urban form shaped by colonization.11

I cannot say that I have succeeded in that attempt, as my frame of reference is mainly Western and therefore tied into the longer tradition that Harris maintains we most move away from. One way to think about this in a useful and theoretical way is to look at urban fabric of Mumbai – its past, present, and future, as parts of the kinetic and static city. Architect and urbanist Rahul Mehrotra put forth this proposition as a means to understanding and reconciling disparate aspects of the urban environment. Mehrotra asserts:

Today in our urban areas there exist two cities – the static and kinetic – two completely different worlds that cohabit the same urban space. The static city is represented through its architecture and by monuments built in permanent materials. The kinetic city that occupies interstitial space is the city of motion – the kuttcha city, built of temporary material.

In a way, Mehrotra’s conservation work in Mumbai through the Urban Design Research Institute speaks directly to the intellectual challenges put forth by Harris. Mehrotra is cognizant of two very important aspects of conservation in Mumbai. First, that the Victorian core represents the exclusion and repression of British colonization. Second, that while this is true, the cohesive face of the area is in fact a relief from the sprawling nature of the millennial megalopolis. He does not see these two points as contrary to the need for conservation, but as facts that need to be acknowledged in the planning process. This is the complexity of conservation in the post-colonial, post-industrial, post-Independence, millennial moment.

Figure 10. Souvenir coffee mugs at Starbucks in Kala Ghoda district, Mumbai. Image depicts Gate of India in New Delhi by Edwin Lutyens.

H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship Google Map

Recommended Readings

Arjun Appadurai, “Spectral Housing and Urban Cleansing: Notes on Millenial Mumbai,” Public Culture 12 no. 3 Fall 2000: 627-651

Arjun Appadurai, “Burning Questions: Arson and Other Public Works in Bombay,” ANY: Architecture New York 18, Public Fear: WHAT'S SO SCARY ABOUT ARCHITECTURE? (1997): 44-47

Bill Ashcroft, “Urbanism, Mobility and Bombay: Reading the Postcolonial City,” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 47 no. 5 (2011): 497-509

Manish Chalana, “Slumdogs vs. Millionaires,” Journal of Architectural Education 63 no. 2 (2010): 25-37

Sandip Hazareesingh, “Colonial Modernism and the Flawed Paradigms of Urban Renewal: Uneven Development in Bombay, 1900–25,” Urban History 28 no. 2 (August 2001): 235 - 255

Meera Kosambi and John E. Brush, “Three Colonial Port Cities in India,” Geographical Review 78 no. 1 (January 1988): 32-47

Rahul Mehrotra, “Constructing Cultural Significance: Looking at Bombay’s Historic Fort Area,” Future Anterior 1 no. 2 (2004): 25-31

Kaiwan Mehta, Alice in Bhuleshwar: Navigating a Mumbai Neighbourhood (New Delhi: Yoda Press, 2009)

Radhika Savant Mohit and H. Detlef Kammeier, “The Fort: Opportunities for an Effective Urban Conservation Strategy in Bombay,” Cities 13 no. 6 (1996): 387-398

Michael Pacione, “Mumbai,” Cities 23 no. 3 (2006): 229–238

Howard Spodek, “Studying the History of Urbanization in India,” Journal of Urban History 6 no 3 (May 1980): 251-295

Stuart Tappin, “The Early Use of Reinforced Concrete in India,” Construction History 18 (2002): 79-98

Michael Windover, “Exchanging Looks: ‘Art Dekho’ Movie Theatres in Bombay,” Architectural History 52 (2009): 201-232

1. See Rashmi Varma, “Provincializing the Global City: From Bombay to Mumbai,” Social Text 22 no. 4 (Winter 2004): 65-89.

2. I will refer to the city as “Mumbai” when discussing present context and “Bombay” in the historical context.

3. Partha Mitter, “The Early British Port Cities of India: Their Planning and Architecture Circa 1640-1757,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 45 no. 2 (June 1986): 102; Meera Kosambi, “Commerce, Conquest and the Colonial City: Role of Locational Factors in Rise of Bombay,” Economic and Political Weekly 20 no. 1 (January 5, 1985): 34. See also Frank Conlon, “Caste, Community, and Colonialism: "The Elements of Population Recruitment and Urban Rule in British Bombay: 1665-1830,” Journal of Urban History 11 no. 2 (February 1985): 181-208 and Amy Karafin, “Around Mumbai in 7 Faiths,” Lonely Planet September, 19 2012 http://www.lonelyplanet.com/india/mumbai-bombay/travel-tips-and-articles/77468.

4. This is only possible due to nineteenth century land reclamation projects.

5. Preeti Chopra, “Refiguring the Colonial City: Recovering the Role of Local Inhabitants in the Construction of Colonial Bombay, 1854-1918,” Buildings & Landscapes 14 (Fall 2007): 110.

6. Tata financed the construction of the Taj Mahal Hotel (1903).

7. See Gijsbert Oonk, “The Emergence of Indigenous Industrialists in Calcutta, Bombay, and Ahmedabad, 1850–1947,” Business History Review 88 (Spring 2014): 43–71 and Talinn Grigor, “Parsi Patronage of the Urheimat,” Getty Research Journal no. 2 (2010): 53-68.

8. Christopher W. London, “High Victorian Bombay: Historic, Economic and Social Influences on Its Architectural Development,” South Asian Studies 13 no. 1 (1997): 101.

9. Jyoti Hosagrahar, “South Asia: Looking Back, Moving Ahead-History and Modernization,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 61 no. 3 (September 2002): 358.

10. The mills in particular have a rich connection to the labor and freedom movements in India. For research on their history and potential for adaptive reuse see INTBAU India, “Mumbai Mills Report, Analysis & Conclusions of INTBAU India Workshop,” March 2005 and Alain Bertaud, “The Formation of Urban Spatial Structures: Markets vs. Design,” Marron Institute of Urban Management http://marroninstitute.nyu.edu/content/working-papers/the-formation-of-urban-spatial-structures.

11. Andrew Harris, “The Metonymic Urbanism of Twenty-first-century Mumbai,” Urban Studies 49 no. 13 (October 2012): 2966.