-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Bury the Lantern: The Other Side of Promoting Farm Electrification

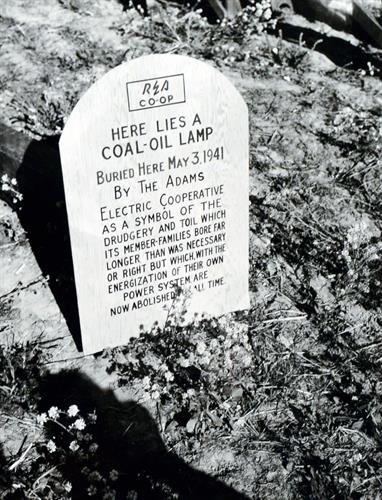

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, numerous farm communities across the United States gathered to enact lantern funerals, the ritualized interring of antiquated kerosene lamps. Cloaked in the guise of mourning, these parodic rites were actually celebrations of the arrival of electric lighting in the rural landscape. In some cases, the burial plot was marked with a tombstone such as the one seen in Figure 1, which explains that the “coal-oil lamp” has been “abolished for all time” by the advent of electricity. In this example, the tombstone was created for an electric cooperative receiving funding from the Rural Electrification Administration (or REA). REA had been founded in 1935 under the New Deal to promote the expedient spread of electricity to America’s farms and rural communities. At the time of its founding, only around 11% of US farms were connected to central station electricity. To address this lack, REA developed a system of making loans directly to farming cooperatives to fund the extension of existing electric lines or pay for the construction of new generating facilities.

Figure 1: Tombstone for a kerosene lamp. The epitaph reads, “Here lies a coal-oil lamp. Buried here May 3, 1941 by the Adams Electric Cooperative as a symbol of the drudgery and toil which its member-families bore far longer than was necessary or right but which, with the energization of their own power system are now abolished for all time.” Image Credit: Record Group 221, Records of the Rural Electrification Administration, Department of Agriculture. Rural Electrification Administration. Photographic Prints of Electrification and Telephone Improvements in the Rural United States, 1936 - 1964. National Archives Identifier: 540048, HMS Entry Number: 221-P.

At the upcoming SAH 2015 Annual Conference, as part of the panel “Architecture in a New Light” I presented a paper that explores how REA both encouraged and co-opted rural enthusiasm for electric lighting in its efforts to modernize the landscape of the American farm. This paper developed as a natural outgrowth of my dissertation, which examines the architecture and landscapes of rural electrification in the United States from 1935 to 1945. Combing through REA’s papers at the National Archives in Kansas City, I encountered dozens of pamphlets, advertisements, and wiring guides that constitute a print media discourse around rural lighting. REA and its partner corporations, including General Electric and Westinghouse, recognized that electric illumination represented a major transformation of farm life. In these publications, which date from the late 1930s and 1940s, lighting is shown as the harbinger of further electric modernization, part of a larger matrix of electric devices that comprise a comprehensive vision of all-electric farm living. This discourse of rural electric lighting and its promises for farm modernization more broadly are the focuses of my SAH paper. When I was invited to write this blog entry, I thought it would be interesting to examine the flip side—not the lionization of electricity, but the vilification of kerosene.

REA’s promotion of electric lighting was part of a institutional practice known as “load-building,” or encouraging farmers to adopt a range of electrified devices in order to ensure that cooperatives were using enough electricity for the government’s loans to be fruitful. Beyond aspiring to recoup government loans, REA hoped to spur the technological modernization of American farmsteads on a larger scale. In line with previous rural reform efforts, REA sought to bring the farmhouse up to an urban standard and to rationalize the farmstead following the efficient model of industrial production.[1] In REA publications, electric light was used as a synecdoche for technological modernity on the farm—a literal and figurative “enlightenment”of farm life. By contrast, the “old coal-oil lamp” was cast as the antithesis of these ideas.

In reality, the transition from kerosene to electric light was one of the most significant technological upgrades enabled by electrification. Many farmers already had access to other energy technologies that did not require central station electricity, such as batteries, liquid petroleum gas, and gasoline that powered radios, stoves, and engines. The switch to electricity from these technologies certainly represented a change, but not the same dramatic improvement that electric lighting offered over its predecessor. In the late 1930s, the majority of American agricultural populations still relied on kerosene lanterns for light both inside the farmhouse and on the farm. Dirty, arduous to maintain, and dangerous, these oil-burning lamps became a kind of symbol, as the tombstone epitaph in Figure 1 suggests, of all the “drudgery and toil” of pre-electrification farm living. One study by the American Society of Electrical Engineers Committee on Uses of Electric Light in Agriculture found that electric light saved farmers an hour and a half a day on average doing their chores, halving the required time with a coal-oil lamp.[2]

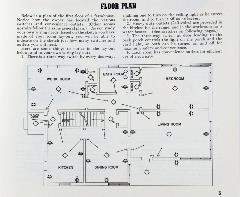

Figure 2: (left) Farmhouse Floor Plan with outlets and lighting, (right) Living Room lighting and wiring diagram showing light switches and convenience outlets. Image Credit: Planning Your Farmstead Wiring and Lighting. Washington, D.C: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Rural Electrification Administration, 1946.

Figure 2: (left) Farmhouse Floor Plan with outlets and lighting, (right) Living Room lighting and wiring diagram showing light switches and convenience outlets. Image Credit: Planning Your Farmstead Wiring and Lighting. Washington, D.C: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Rural Electrification Administration, 1946.

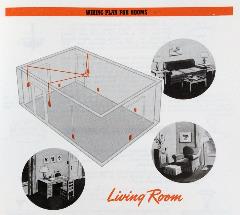

Additionally, depictions of rural spaces illuminated by kerosene lanterns were set in contrast to those bathed in the steady, even glow of electric light. Illustrations, such as the one in Figure 2, link electric lighting to a new kind of spatial order, showing the farm as a series of circuit diagrams as farm families were urged to plan ahead for future lighting purchases and additional electrified conveniences. The spaces of kerosene, by contrast, were shown as cluttered, dim, and uncomfortable. For example, the cartoon seen below, captioned “Born Thirty Years Too Soon,” depicts a family attempting to enjoy nighttime leisure, all relying on the glow provided by a single kerosene lamp (Figure 3). As one family member precariously hoists the lamp to search for a misplaced book, the rest of the family is thrown into darkness and frustration. The relatively small sphere of illumination provided by a single kerosene lamp was also dramatized in filmmaker Joris Iven’s 1940 documentary for REA, Power and the Land, which tells the story of one family’s transition to electric power. The first half of the film, which depicts pre-electrification life on the farm, charts the daytime task of scouring and maintaining kerosene lamps and gloomy, atmospheric evenings huddled around a single lamp (Figure 4). Although electric bulbs were in fact 16-20 times brighter than the kerosene lamps they replaced, REA reinforced and even exaggerated the magnitude of this change in print media and film, conflating kerosene with pre-modern spaces and electric lighting with modern ones.[3]

Figure 3: J.R. Williams, “Born Thirty Years Too Soon,” Rural Electrification News 1, no. 12 (August 1936): 24.

Figure 4: Film still from Power and the Land (director Joris Ivens for REA, 1940). Image Credit: Record Group 221, Records of the Rural Electrification Administration, Department of Agriculture. Rural Electrification Administration. Photographic Prints of Electrification and Telephone Improvements in the Rural United States, 1936 - 1964. National Archives Identifier: 540048, HMS Entry Number: 221-P.

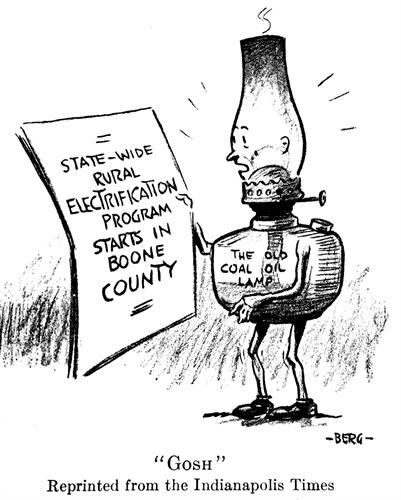

Personifications of the kerosene lantern, such as the one in Figure 5 or the actual lanterns buried as part of mock funerals went even further, suggesting that farmers who still burned kerosene embodied negative rural stereotypes of being behind-the-times, backwards, or stuck in their ways. Yet the burying of the kerosene lamp did not mean the end to this technology. Despite all of this negative publicity, most farm families still kept kerosene lanterns in case of a power outage, a relatively common occurrence during the early years of electrification. As with much of the electrification process, rural America’s conversion to electric light was selective and gradual.

Figure 5: Berg, “Gosh,” reprinted from the Indianapolis Times in Rural Electrification News 1, no. 7 (March 1936): 22.

Recommended Reading

Adams, Jane. The Transformation of Rural Life: Southern Illinois, 1890-1990. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.Brown, D. Clayton. Electricity for Rural America: The Fight for the REA. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1980.

Fitzgerald, Deborah K. Every Farm a Factory: The Industrial Ideal in American Agriculture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Jellison, Katherine. Entitled to Power: Farm Women and Technology, 1913-1963. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Kline, Ronald R. Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

Nye, David E. Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880-1940. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1990.

Tobey, Ronald C. Technology As Freedom: The New Deal and the Electrical Modernization of the American Home. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Sarah Rovang is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of Art & Architecture at Brown University. Her dissertation Modernization and Architecture Under the Rural Electrification Administration, 1935–1945,explores the intersection of electricity, architecture, and the rural landscape in the United States during the New Deal. Her work has been supported by fellowships from the New England Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians and the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami.

Sarah Rovang is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of Art & Architecture at Brown University. Her dissertation Modernization and Architecture Under the Rural Electrification Administration, 1935–1945,explores the intersection of electricity, architecture, and the rural landscape in the United States during the New Deal. Her work has been supported by fellowships from the New England Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians and the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami.

[1] See Kline, Jellison, and Fitzgerald in Recommended Reading below.

[2] “Electric Lights Save Farm an Hour and a Half a Day in Doing Chores,” Rural Electrification News 4, no. 7 (March 1939): 22.

[3] Lawrence C. Porter, “Good Lighting Inside and Outside the Farmhouse,” Rural Electrification News 3, no. 1 (September 1937): 3.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top