-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Spanish Itineraries, Part 1: Barcelona to Ronda

The first part of my travels in Spain led me from Barcelona to Malaga, Granada, Cordoba, Seville, and Ronda. Later in the fellowship year, I will report from Madrid and northern Spain, yet at this stage, Barcelona and Andalusia are the focus.

Barcelona, a city I have long wanted to visit, is not related to my research on medieval Islamic architecture, and hence my itinerary began with a destination draws most visitors to Barcelona: the Sagrada Familia. This enormous church, begun by Barcelona architect Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926) in 1883 remained unfinished at its creator’s death and is still a work in progress scheduled to be completed in 2026, although it was consecrated in 2010. In its present stage, the building appears rough and unfinished on the outside, while in the interior appears complete. The central nave with its vault (Figure 1) evokes Gothic architecture and, at the same time, the bone structure of a large animal. The stained glass windows in the side aisles (Figure 2) appear Gothic at first sight while in their details, they again connect to the organic structure of the interior.

Figure 1: Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, vault of central nave (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, stained glass windows in aisle

On the exterior, the sculpted program evolves in a variety of styles ranging from neo-Gothic to the angular figures created by Josep Maria Subirachs (1927–2014), such as the Veronica (Figure 3) on the so-called Passion Façade, on which the Catalan sculptor work from 1986 until 2009.

Figure 3: Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Veronica on Passion Façade (P. Blessing)

Gaudí‘s work is present throughout Barcelona; his most well-known residential building is the Casa Battló, a structure that from far evokes bones, and hence carries the nickname Casas dels Osos (House of Bones). Rather than the Casa Battló itself, however, the contrast between its architecture and that of adjoining Casa Amatller with its neo-Gothic façade, porte cochère, and interior courtyard is striking (Figure 4). Both buildings were completed within years of each other: Gaudí’s Casa Battló in 1906, and Casa Amatller, a work of Josep Puig i Catafalch (1867–1956), in 1900. The tensions inherent in the contrast between the two buildings are part of the larger discussion around Modernista architecture in Barcelona, a topic to be explored in more detail.

Figure 4: Casa Amatller (left) and Casa Battló, Barcelona, details of facades (P. Blessing)

Moving from the center of Barcelona to the hilly area of Montjuic, the Museu Nacional de Arte de Catalunya was one of the centerpieces of my stay. Particularly impressive was the large collection of Romanesque wall paintings from churches in the wider region of Barcelona. Examples include the full decoration of the church of Santa Maria de Taull (c. 1123), which are carefully displayed—just as the other paintings in the collection—in a structure replicating the original architecture (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The author in front of the apse from Santa Maria de Taull (A. Yaycioglu)

The move from Barcelona to Andalusia meant a change at many levels: weather, landscape, food, and architecture. For the remainder of this post, I will focus on the remains of Islamic architecture and their later adaptation into Christian structures in some cases.

After a long train journey from Barcelona, Malaga was the first stop. Dominating this costal city stands the Alcazaba, a fortification that includes a palace last expanded in the fourteenth century when Malaga was under Nasrid rule. Due to the smaller size, the fortifications are always evident while moving through the palace. In the interior, the palace is in many ways an Alhambra on a smaller scale, with a series of courtyards, gardens, and miradors. Water runs through large parts of the complex (Figures 6 and 7) and is gathered in pools that produce mirror effects (Figure 8).

Figures 6, 7, 8: Water courses in the Alcazaba, Malaga (P. Blessing)

Decoration consists of stucco (Figure 9) and carved wood, and sequences of intersecting arches in various shapes and sizes, some elaborately decorated, are used to create varied viewpoints (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 9: Detail of stucco decoration, Alcazaba, Malaga (P. Blessing)

Figures 10 and 11: Details of arches, Alcazaba, Malaga (P. Blessing)

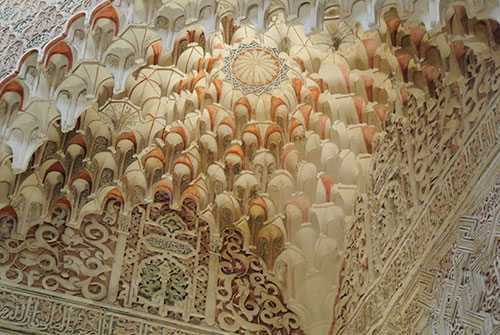

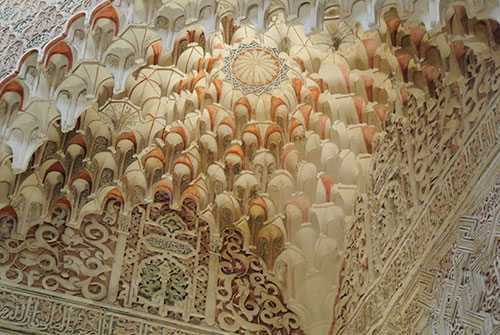

In Granada, the Alhambra (Figure 12) is an even more prominent focus both due to its location and size, and its prominence. Most striking while visiting are the differences in scale between the overall complex—fortifications, palaces, gardens all included—and the core of the structure, the so-called Nasrid palaces. In the latter, built in the early to mid-fourteenth century by a succession of Granada’s rulers, do we find the famous sections such as the Court of Myrtles (Figure 13), the Court of Lions (Figure 14), and the Hall of the Abencerrajes (Figure 15): structures that have nurtured fantasies of nostalgia since the nineteenth century, when the Alhambra once more came into public view after centuries of neglect.

Figure 12: Alhambra, Granada, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 13: Alhambra, Granada, reflection of the Comares Tower in the pool of the Court of Myrtles (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Alhambra, Granada, detail of fountain (copy or original), Court of Lions (P. Blessing)

Figure 15: Alhambra, Granada, Hall of the Abencerrajes, interior view of muqarnas dome (P. Blessing)

Within the Nasrid palaces, the effect is one of a structure at once intimate and geared to impress; nothing is left to chance, and the smallest element in the architectural decoration in stucco, wood, and tile is employed within the overall program. In the Comares Hall the stucco decoration, combining inscriptions with geometric and vegetal decoration, seemingly hangs from the walls in the guise of fabric (Figure 16). The inscriptions in the monument—Qur’an passages, Nasrid mottoes, but also verses describing the beauty of the palaces, at times making it speak—abound; the full texts are available in José Miguel Puerta Vílchez’s book Reading the Alhambra. In details of the varied techniques used to decorate different sections of the building, visual effects intersect in a complex combination of motifs and material properties (Figures 17 and 18). In addition, mirror images of buildings on water are a consistent feature across the complex, in the Courtyard of Myrtles, but also the Partal Palace (Figure 19).

Figure 16: Alhambra, Granada, Comares Hall, interior view (P. Blessing)

Figure 17: Alhambra, Granada, detail of tile dado in the Courtyard of Myrtles (P.Blessing)

Figure 18: Alhambra, Granada, detail of stucco on the Comares Façade (P.Blessing)

Figure 19: Alhambra, Granada, Partal (P. Blessing)

The historical center of Granada, at the foot of the Alhambra, offers a different view on the monument, but also the city. A souvenir industry focusing on the Islamic heritage of Andalusia has emerged: copies of stuccoes in the Alhambra are for sale, but also objects—ranging from crafts to kitsch—that would be equally at home in the tourist markets of Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey. Some restaurants offer halal meat dishes, catering to Muslim tourists, and part of a halal tourism industry that has picked up in the region in recent years.1 Not many Islamic monuments remain; among them, the fourteenth-century Madraza (Figure 20) is remarkable for its original painted decoration, carefully restored between 2007 and 2011. Contemporary to the Alhambra, this monument reflects what the stucco of the Nasrid palaces, which have lost most of their polychromy, would have looked like. Only the small mosque of this madrasa remains behind a Baroque façade.

Figure 20: Madraza, Granada, detail of painted muqarnas (P. Blessing)

In Cordoba, the main monument is of course the Great Mosque, founded in 784 by the Umayyad ruler of al-Andalus and expanded several times in the ninth and tenth century. After the Christian reconquest of Cordoba in 1236, the building became the city’s cathedral, a function it retains until today. In the sixteenth century, a large late Gothic cathedral was built into the center of the prayer hall, effectively destroying the unity of the columns. While standing within the mosque, it is still possible to find viewpoints that obscure the insertions, and provide the impression that a tenth-century visitor might have had (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Great Mosque, Cordoba, interior view (P. Blessing)

Figure 22: Great Mosque, Cordoba, maqsura, view of dome in front of central mihrab (P. Blessing)

The maqsura of the mosque, with the mihrab covered in gold mosaic remain intact (Figure 22). Even seen from the point in the prayer hall where the entrance would have been in 965, after the maqsura commissioned by Umayyad caliph al-Hakam II was completed (Figure 22). Nowadays, the interior of the mosque remains dark, yet this may in part be the effect of the transformation into a church, when the arcades opening into the courtyard were closed (Figure 23). Seen from across the Guadalquivir, the major river connecting Cordoba to Seville, where a major trade port was located in the Middle Ages, the cathedral appears above the original roof (Figure 24).

Figure 23: Great Mosque, Cordoba, former entrances to prayer hall (P. Blessing)

Figure 24: Great Mosque, Cordoba, view from Torre de la Qalahorra (P. Blessing)

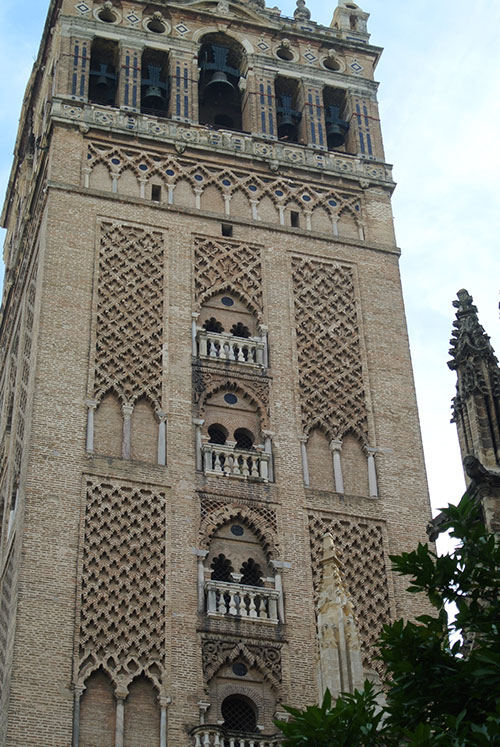

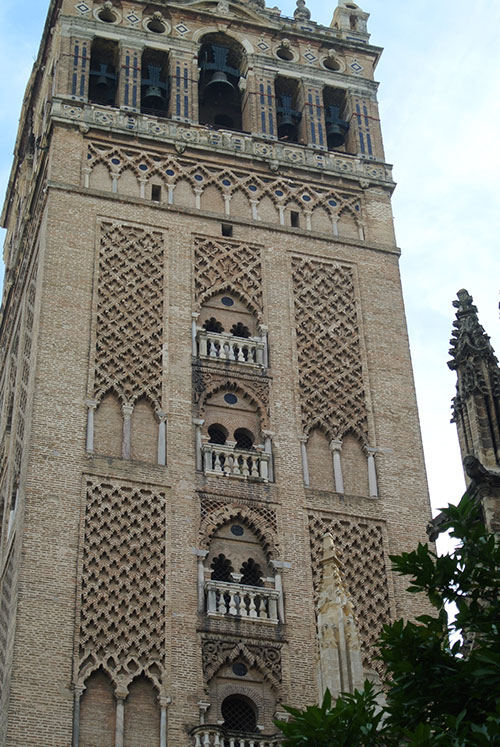

The question of transforming mosques into cathedrals is also pertinent in Seville. Here, the Great Mosque, an Almohad foundation begun in 1172, was transformed into a cathedral in 1248 and used largely unchanged until the early fifteenth century. At that point, the prayer hall was torn down and replaced by a Gothic cathedral (Figure 25). Nevertheless, several elements of the mosque remain: the minaret (Figure 26), known as Giralda, built in 1184, stands complete with only few additions and the walls of the courtyard remain largely intact (Figures 27 and 28). The Almohad architecture visible here will be a central topic in my November post from Morocco.

Figure 25: Cathedral, Seville, detail of vault (P. Blessing)

Figure 26: Giralda, Seville, as seen from mosque courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 27: View of mosque courtyard from Giralda (P. Blessing)

Figure 28: View across mosque courtyard (P. Blessing)

I leave the reader with an interior view of a less well-known monument, a fourteenth-century hamam in Ronda, a small mountain town between Seville and Malaga. It was one of the surprises that Andalusia had to offer on a trip on which I embarked well prepared for some sites, but as it turned out, not all.

Figure 29: Hamam, Ronda, interior view of main room (P. Blessing)

Irwin, Robert. The Alhambra (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004).

Khoury, Nuha. “The meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the tenth century,” Muqarnas 13 (1996): 80–98.

Puerta Vílchez, José Miguel. Reading the Alhambra: A Visual Guide to the Alhambra through Its Inscriptions (Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, 2011).

Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000).

Barcelona, a city I have long wanted to visit, is not related to my research on medieval Islamic architecture, and hence my itinerary began with a destination draws most visitors to Barcelona: the Sagrada Familia. This enormous church, begun by Barcelona architect Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926) in 1883 remained unfinished at its creator’s death and is still a work in progress scheduled to be completed in 2026, although it was consecrated in 2010. In its present stage, the building appears rough and unfinished on the outside, while in the interior appears complete. The central nave with its vault (Figure 1) evokes Gothic architecture and, at the same time, the bone structure of a large animal. The stained glass windows in the side aisles (Figure 2) appear Gothic at first sight while in their details, they again connect to the organic structure of the interior.

Figure 1: Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, vault of central nave (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, stained glass windows in aisle

On the exterior, the sculpted program evolves in a variety of styles ranging from neo-Gothic to the angular figures created by Josep Maria Subirachs (1927–2014), such as the Veronica (Figure 3) on the so-called Passion Façade, on which the Catalan sculptor work from 1986 until 2009.

Figure 3: Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Veronica on Passion Façade (P. Blessing)

Gaudí‘s work is present throughout Barcelona; his most well-known residential building is the Casa Battló, a structure that from far evokes bones, and hence carries the nickname Casas dels Osos (House of Bones). Rather than the Casa Battló itself, however, the contrast between its architecture and that of adjoining Casa Amatller with its neo-Gothic façade, porte cochère, and interior courtyard is striking (Figure 4). Both buildings were completed within years of each other: Gaudí’s Casa Battló in 1906, and Casa Amatller, a work of Josep Puig i Catafalch (1867–1956), in 1900. The tensions inherent in the contrast between the two buildings are part of the larger discussion around Modernista architecture in Barcelona, a topic to be explored in more detail.

Figure 4: Casa Amatller (left) and Casa Battló, Barcelona, details of facades (P. Blessing)

Moving from the center of Barcelona to the hilly area of Montjuic, the Museu Nacional de Arte de Catalunya was one of the centerpieces of my stay. Particularly impressive was the large collection of Romanesque wall paintings from churches in the wider region of Barcelona. Examples include the full decoration of the church of Santa Maria de Taull (c. 1123), which are carefully displayed—just as the other paintings in the collection—in a structure replicating the original architecture (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The author in front of the apse from Santa Maria de Taull (A. Yaycioglu)

The move from Barcelona to Andalusia meant a change at many levels: weather, landscape, food, and architecture. For the remainder of this post, I will focus on the remains of Islamic architecture and their later adaptation into Christian structures in some cases.

After a long train journey from Barcelona, Malaga was the first stop. Dominating this costal city stands the Alcazaba, a fortification that includes a palace last expanded in the fourteenth century when Malaga was under Nasrid rule. Due to the smaller size, the fortifications are always evident while moving through the palace. In the interior, the palace is in many ways an Alhambra on a smaller scale, with a series of courtyards, gardens, and miradors. Water runs through large parts of the complex (Figures 6 and 7) and is gathered in pools that produce mirror effects (Figure 8).

Figures 6, 7, 8: Water courses in the Alcazaba, Malaga (P. Blessing)

Decoration consists of stucco (Figure 9) and carved wood, and sequences of intersecting arches in various shapes and sizes, some elaborately decorated, are used to create varied viewpoints (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 9: Detail of stucco decoration, Alcazaba, Malaga (P. Blessing)

Figures 10 and 11: Details of arches, Alcazaba, Malaga (P. Blessing)

In Granada, the Alhambra (Figure 12) is an even more prominent focus both due to its location and size, and its prominence. Most striking while visiting are the differences in scale between the overall complex—fortifications, palaces, gardens all included—and the core of the structure, the so-called Nasrid palaces. In the latter, built in the early to mid-fourteenth century by a succession of Granada’s rulers, do we find the famous sections such as the Court of Myrtles (Figure 13), the Court of Lions (Figure 14), and the Hall of the Abencerrajes (Figure 15): structures that have nurtured fantasies of nostalgia since the nineteenth century, when the Alhambra once more came into public view after centuries of neglect.

Figure 12: Alhambra, Granada, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 13: Alhambra, Granada, reflection of the Comares Tower in the pool of the Court of Myrtles (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Alhambra, Granada, detail of fountain (copy or original), Court of Lions (P. Blessing)

Figure 15: Alhambra, Granada, Hall of the Abencerrajes, interior view of muqarnas dome (P. Blessing)

Within the Nasrid palaces, the effect is one of a structure at once intimate and geared to impress; nothing is left to chance, and the smallest element in the architectural decoration in stucco, wood, and tile is employed within the overall program. In the Comares Hall the stucco decoration, combining inscriptions with geometric and vegetal decoration, seemingly hangs from the walls in the guise of fabric (Figure 16). The inscriptions in the monument—Qur’an passages, Nasrid mottoes, but also verses describing the beauty of the palaces, at times making it speak—abound; the full texts are available in José Miguel Puerta Vílchez’s book Reading the Alhambra. In details of the varied techniques used to decorate different sections of the building, visual effects intersect in a complex combination of motifs and material properties (Figures 17 and 18). In addition, mirror images of buildings on water are a consistent feature across the complex, in the Courtyard of Myrtles, but also the Partal Palace (Figure 19).

Figure 16: Alhambra, Granada, Comares Hall, interior view (P. Blessing)

Figure 17: Alhambra, Granada, detail of tile dado in the Courtyard of Myrtles (P.Blessing)

Figure 18: Alhambra, Granada, detail of stucco on the Comares Façade (P.Blessing)

Figure 19: Alhambra, Granada, Partal (P. Blessing)

The historical center of Granada, at the foot of the Alhambra, offers a different view on the monument, but also the city. A souvenir industry focusing on the Islamic heritage of Andalusia has emerged: copies of stuccoes in the Alhambra are for sale, but also objects—ranging from crafts to kitsch—that would be equally at home in the tourist markets of Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey. Some restaurants offer halal meat dishes, catering to Muslim tourists, and part of a halal tourism industry that has picked up in the region in recent years.1 Not many Islamic monuments remain; among them, the fourteenth-century Madraza (Figure 20) is remarkable for its original painted decoration, carefully restored between 2007 and 2011. Contemporary to the Alhambra, this monument reflects what the stucco of the Nasrid palaces, which have lost most of their polychromy, would have looked like. Only the small mosque of this madrasa remains behind a Baroque façade.

Figure 20: Madraza, Granada, detail of painted muqarnas (P. Blessing)

In Cordoba, the main monument is of course the Great Mosque, founded in 784 by the Umayyad ruler of al-Andalus and expanded several times in the ninth and tenth century. After the Christian reconquest of Cordoba in 1236, the building became the city’s cathedral, a function it retains until today. In the sixteenth century, a large late Gothic cathedral was built into the center of the prayer hall, effectively destroying the unity of the columns. While standing within the mosque, it is still possible to find viewpoints that obscure the insertions, and provide the impression that a tenth-century visitor might have had (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Great Mosque, Cordoba, interior view (P. Blessing)

Figure 22: Great Mosque, Cordoba, maqsura, view of dome in front of central mihrab (P. Blessing)

The maqsura of the mosque, with the mihrab covered in gold mosaic remain intact (Figure 22). Even seen from the point in the prayer hall where the entrance would have been in 965, after the maqsura commissioned by Umayyad caliph al-Hakam II was completed (Figure 22). Nowadays, the interior of the mosque remains dark, yet this may in part be the effect of the transformation into a church, when the arcades opening into the courtyard were closed (Figure 23). Seen from across the Guadalquivir, the major river connecting Cordoba to Seville, where a major trade port was located in the Middle Ages, the cathedral appears above the original roof (Figure 24).

Figure 23: Great Mosque, Cordoba, former entrances to prayer hall (P. Blessing)

Figure 24: Great Mosque, Cordoba, view from Torre de la Qalahorra (P. Blessing)

The question of transforming mosques into cathedrals is also pertinent in Seville. Here, the Great Mosque, an Almohad foundation begun in 1172, was transformed into a cathedral in 1248 and used largely unchanged until the early fifteenth century. At that point, the prayer hall was torn down and replaced by a Gothic cathedral (Figure 25). Nevertheless, several elements of the mosque remain: the minaret (Figure 26), known as Giralda, built in 1184, stands complete with only few additions and the walls of the courtyard remain largely intact (Figures 27 and 28). The Almohad architecture visible here will be a central topic in my November post from Morocco.

Figure 25: Cathedral, Seville, detail of vault (P. Blessing)

Figure 26: Giralda, Seville, as seen from mosque courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 27: View of mosque courtyard from Giralda (P. Blessing)

Figure 28: View across mosque courtyard (P. Blessing)

I leave the reader with an interior view of a less well-known monument, a fourteenth-century hamam in Ronda, a small mountain town between Seville and Malaga. It was one of the surprises that Andalusia had to offer on a trip on which I embarked well prepared for some sites, but as it turned out, not all.

Figure 29: Hamam, Ronda, interior view of main room (P. Blessing)

Suggested Readings:

Grabar, Oleg. The Alhambra (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978).Irwin, Robert. The Alhambra (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004).

Khoury, Nuha. “The meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the tenth century,” Muqarnas 13 (1996): 80–98.

Puerta Vílchez, José Miguel. Reading the Alhambra: A Visual Guide to the Alhambra through Its Inscriptions (Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, 2011).

Ruggles, D. Fairchild. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top