-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Byzantium in Istanbul, or: Istanbul is Constantinople (among other things)

Just hours before I sat down to write this text on March 19, 2016, another suicide bomb claimed victims in Turkey, this time on İstiklal Caddesi, a lively shopping street at the center of Istanbul’s European side. Last week, an attack in one of Ankara’s main public transportation hubs pointed to further troubles, and it is now clearer how soon they are to some. So far, I have only very occasionally touched upon the political reality of the Middle East, and increasingly Europe. Yet now, as I continued research in Turkey and observe how the situation develops locally, I am both at a loss for words. I feel that it is callous to write about architectural history without the larger context of a country that increasingly slides into violence and uncertainty. I ambitiously wanted to write about Bursa, the first Ottoman capital, as well, but given recent events do not have the stomach to venture into a description of monuments that are, on the one hand, ethereally beautiful and, on the other hand, include mausolea and graveyards. I may return to this later, with distance if possible, but for now the first paragraph of my original text below stands without actual continuation.

Last month, I wrote about the transformation of Constantinople to Istanbul (although the shifts in naming were not as simple as this sentence suggests). I did not, however, say much about Byzantine architecture in Istanbul, nor did I venture into other cities. This post will do just that: first, it will present Byzantine monuments extant in Istanbul and second, it will show how in Bursa, the first Ottoman capital from 1326 to c. 1368, Byzantine architecture became part and parcel of the new dynasty’s patronage.

Figure 1: View of restored section of city walls near the Topkapı (not to be confused with the palace) tramway station, extra muros (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: City walls and highway at Ayvansarayı (P. Blessing)

In Istanbul, a main feature of the Byzantine city that is still preserved are parts of the walls, although heavily restored in some (Figure 1) and badly preserved in other sections (Figure 2). Restoration and urban renewal projects close to the walls have caused controversy in recent years: the entire neighborhood of Sulukule, heavily populated by Roma communities, was demolished and inhabitants relocated. In recent months, the vegetable gardens (bostanlar) that existed along the walls for centuries, providing subsistence to local families and produce to some of Istanbul’s markets, were bulldozed. Often, historical photographs of the walls are now the only reliable sources to study certain sections; the photographs taken by Nicholas V. Artamonoff in the 1930s and 1940s are examples (Figure 3).

Figure 3: General view of the Wall of Manuel Komnenos looking from the city. Market garden, orchards, and shed in foreground, Photographer: Nicholas V. Artamonoff, Date: January 1938, Negative Number: RA415, Reaccession Number:

ICFA.NA.0240, Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection, Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

Similarly, former Byzantine churches have often undergone a series of restorations and transformations, from church to mosque, from mosque to museum, and sometimes back to mosque. Many of these monuments are located in an area between the land walls and the Süleymaniye Mosque. They date from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries, although the ruins of the sixth-century Hagious Polyeuktos (Figure 4) can bee seen close to the sixteenth-century Şehzade Mosque and the aqueduct of Valens (Figure 5). The site was excavated in the 1930s, and sculpture is on view at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, while spolia have been part of the Church of St. Marc in Venice since the thirteenth century (Figure 6). This is one of the instances where several stations of my travels this year form a whole, displaying connections that are not easily understood without first-hand experience.

Figure 4: remains of large-scale sculpture from Hagios Polyeuktos, photograph taken in August 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 5: aqueduct of Valens, Şehzade Mosque, near photograph taken in August 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: spolia from Hagios Polyeuktos, now on St. Mark’s Cathedral, Venice (P. Blessing)

Moving away from Hagios Polyeuktos towards the city wall, the next site of interest is the church of the Pantokrator Monastery, known as Zeyrek Mosque since the late fifteenth century (Figure 7). Close by is the Fatih Mosque, one of the monuments that I wrote about in February.

Figure 7: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque (front) and Fatih Mosque (P. Blessing)

The Pantokrator Church, or rather churches since it was planned as an assembly of structures from the start, was built under the patronage of John II and Eirene Komnenos 1118–36. A main function was that of imperial mausolea, as more of a dozen imperial burials were located there. The structure was restored in a long-term project under the director of Prof. Zeynep Ahunbay, Prof. Metin Ahunbay, and Prof. Robert Ousterhout, beginning in 1997–98, and continued in several seasons until 2005–06. At that point, the Directorate of Pious Foundations (Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü) took over the project, which has been continuing in stages (Figures 8, 9, and 10), and it is currently not accessible.

Figure 8: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 9: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figure 10: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in 2016 (P. Blessing)

Close to the walls, the Chora Church/Kariye Camii (Figure 11) built in the eleventh century and enlarged in 1316–21, has been a museum since the early 1930s. The mosaic decoration of the narthex and naos, and the frescoes in the fourteenth-century funerary chapel are the main attractions of the site. The patron of the fourteenth-century restoration of the church, Theodore Metochites, is shown at the feet of Christ (Figure 12), presenting the restored church—notably with the addition of the mosaics. The extensive program of the narthex, depicting scenes from the life of Christ and the life of the Virgin Mary, culminate in the figure of Christ Pantokrator in the southern dome (Figure 13) and of the Virgin and Child in the northern dome (Figure 14). In the funerary chapel, frescoes dating to c. 1320 show an elaborate program moving towards the Anastasis, and a terrifyingly creative rendering of the

Figure 11: Chora Church, exterior in 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 12: Chora Church, mosaic showing Theodore Metochites as donor (P. Blessing)

Figure 13: Chora Church, southern dome of narthex with Christ Pantokrator (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Chora Church, southern dome of narthex with Christ Pantokrator (P. Blessing)

[This is where I meant to move on to Bursa, but I will leave this for now. My April blog, planned as a text about Madrid and northern Spain, may return to Bursa instead].

Let me close with a paragraph on some issues indirectly connected to the Byzantine past of Istanbul. The first is the site of Eyüp up the Golden Horn outside the old walls, a landscape of Ottoman mosques, mausolea, and graveyards that are still in use today (Figure 15). At the center of this holy site is the tomb of a figure known as Abu Ayyub al-Ansari (Eyüp Sultan on Turkish); the narrative surrounding the tomb is closely connected to the time of Mehmed the Conqueror. According to legend, Abu Ayyub al-Ansari was companion of the Prophet Muhammad who died during the first Arab siege of Constantinople—and thus served as a (less successful) precedent of Mehmed the Conqueror’s conquest, now conveniently connected to early Islamic times. While the city was under siege just before the Ottoman conquest, Akşemsettin, a Sufi shaykh close to the sultan, found the Abu Ayyub al-Ansari’s previously unknown tomb. A mausoleum and mosque were established and the site firmly became part of Ottoman foundational lore.1 The current mosque is that built after a devastating earthquake in the eighteenth century (Figures 16 and 17), although much of the time decoration on the mausoleum consists of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century pieces (Figures 18 and 19).

Figure 15: View over Golden Horn and Eyüp from Pierre Loti Cafe (P. Blessing)

Figure 16: View of Eyüp Sultan Mosque, with graveyard in the foreground (P. Blessing)

Figure 17: Courtyard, Eyüp Sultan Mosque (P. Blessing)

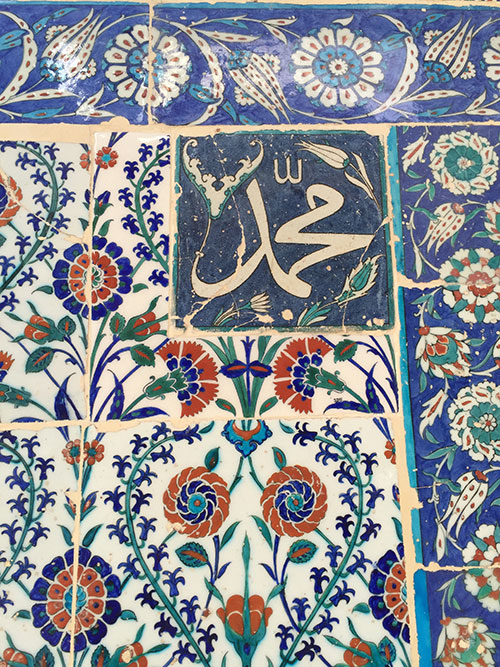

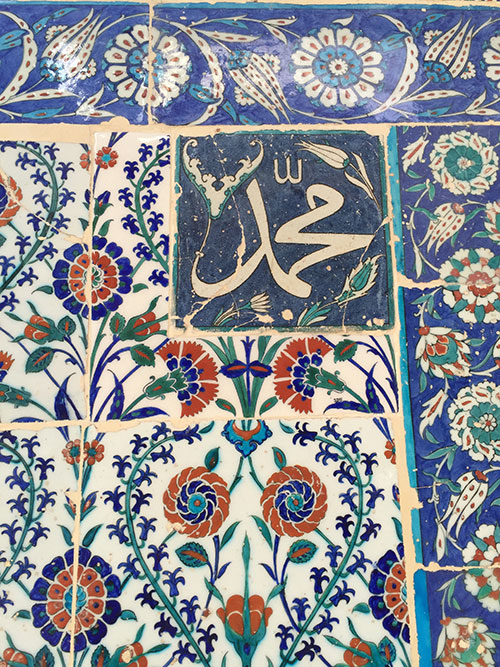

Figures 18 and 19: tiles on façade of mausoleum, Eyüp Sultan Mosque (P. Blessing)

Turning away from Eyüp and the Golden Horn, moving along the shore towards Eminönü, the neighborhoods of Fener and Balat are the most recent sites of the gentrification that has already taken over areas such as Beyoğlu and Cihangir in the last twenty years. Yet here, towering above neighborhoods full of historical buildings—some restored, others in ruins—is the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, a poignant reminder of the city’s history but also its present that is not just Turkish and Islamic (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Balat, view up the hill with Patriarchate at the top (P. Blessing)

1. For the details of various sources on these accounts and the early architectural history of the site, see: Kafescioglu, Constantinopolis/ Istanbul, pp. 45-52.

Last month, I wrote about the transformation of Constantinople to Istanbul (although the shifts in naming were not as simple as this sentence suggests). I did not, however, say much about Byzantine architecture in Istanbul, nor did I venture into other cities. This post will do just that: first, it will present Byzantine monuments extant in Istanbul and second, it will show how in Bursa, the first Ottoman capital from 1326 to c. 1368, Byzantine architecture became part and parcel of the new dynasty’s patronage.

Figure 1: View of restored section of city walls near the Topkapı (not to be confused with the palace) tramway station, extra muros (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: City walls and highway at Ayvansarayı (P. Blessing)

In Istanbul, a main feature of the Byzantine city that is still preserved are parts of the walls, although heavily restored in some (Figure 1) and badly preserved in other sections (Figure 2). Restoration and urban renewal projects close to the walls have caused controversy in recent years: the entire neighborhood of Sulukule, heavily populated by Roma communities, was demolished and inhabitants relocated. In recent months, the vegetable gardens (bostanlar) that existed along the walls for centuries, providing subsistence to local families and produce to some of Istanbul’s markets, were bulldozed. Often, historical photographs of the walls are now the only reliable sources to study certain sections; the photographs taken by Nicholas V. Artamonoff in the 1930s and 1940s are examples (Figure 3).

Figure 3: General view of the Wall of Manuel Komnenos looking from the city. Market garden, orchards, and shed in foreground, Photographer: Nicholas V. Artamonoff, Date: January 1938, Negative Number: RA415, Reaccession Number:

ICFA.NA.0240, Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection, Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

Similarly, former Byzantine churches have often undergone a series of restorations and transformations, from church to mosque, from mosque to museum, and sometimes back to mosque. Many of these monuments are located in an area between the land walls and the Süleymaniye Mosque. They date from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries, although the ruins of the sixth-century Hagious Polyeuktos (Figure 4) can bee seen close to the sixteenth-century Şehzade Mosque and the aqueduct of Valens (Figure 5). The site was excavated in the 1930s, and sculpture is on view at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, while spolia have been part of the Church of St. Marc in Venice since the thirteenth century (Figure 6). This is one of the instances where several stations of my travels this year form a whole, displaying connections that are not easily understood without first-hand experience.

Figure 4: remains of large-scale sculpture from Hagios Polyeuktos, photograph taken in August 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 5: aqueduct of Valens, Şehzade Mosque, near photograph taken in August 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: spolia from Hagios Polyeuktos, now on St. Mark’s Cathedral, Venice (P. Blessing)

Moving away from Hagios Polyeuktos towards the city wall, the next site of interest is the church of the Pantokrator Monastery, known as Zeyrek Mosque since the late fifteenth century (Figure 7). Close by is the Fatih Mosque, one of the monuments that I wrote about in February.

Figure 7: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque (front) and Fatih Mosque (P. Blessing)

The Pantokrator Church, or rather churches since it was planned as an assembly of structures from the start, was built under the patronage of John II and Eirene Komnenos 1118–36. A main function was that of imperial mausolea, as more of a dozen imperial burials were located there. The structure was restored in a long-term project under the director of Prof. Zeynep Ahunbay, Prof. Metin Ahunbay, and Prof. Robert Ousterhout, beginning in 1997–98, and continued in several seasons until 2005–06. At that point, the Directorate of Pious Foundations (Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü) took over the project, which has been continuing in stages (Figures 8, 9, and 10), and it is currently not accessible.

Figure 8: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 9: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figure 10: Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in 2016 (P. Blessing)

Close to the walls, the Chora Church/Kariye Camii (Figure 11) built in the eleventh century and enlarged in 1316–21, has been a museum since the early 1930s. The mosaic decoration of the narthex and naos, and the frescoes in the fourteenth-century funerary chapel are the main attractions of the site. The patron of the fourteenth-century restoration of the church, Theodore Metochites, is shown at the feet of Christ (Figure 12), presenting the restored church—notably with the addition of the mosaics. The extensive program of the narthex, depicting scenes from the life of Christ and the life of the Virgin Mary, culminate in the figure of Christ Pantokrator in the southern dome (Figure 13) and of the Virgin and Child in the northern dome (Figure 14). In the funerary chapel, frescoes dating to c. 1320 show an elaborate program moving towards the Anastasis, and a terrifyingly creative rendering of the

Figure 11: Chora Church, exterior in 2008 (P. Blessing)

Figure 12: Chora Church, mosaic showing Theodore Metochites as donor (P. Blessing)

Figure 13: Chora Church, southern dome of narthex with Christ Pantokrator (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Chora Church, southern dome of narthex with Christ Pantokrator (P. Blessing)

[This is where I meant to move on to Bursa, but I will leave this for now. My April blog, planned as a text about Madrid and northern Spain, may return to Bursa instead].

Let me close with a paragraph on some issues indirectly connected to the Byzantine past of Istanbul. The first is the site of Eyüp up the Golden Horn outside the old walls, a landscape of Ottoman mosques, mausolea, and graveyards that are still in use today (Figure 15). At the center of this holy site is the tomb of a figure known as Abu Ayyub al-Ansari (Eyüp Sultan on Turkish); the narrative surrounding the tomb is closely connected to the time of Mehmed the Conqueror. According to legend, Abu Ayyub al-Ansari was companion of the Prophet Muhammad who died during the first Arab siege of Constantinople—and thus served as a (less successful) precedent of Mehmed the Conqueror’s conquest, now conveniently connected to early Islamic times. While the city was under siege just before the Ottoman conquest, Akşemsettin, a Sufi shaykh close to the sultan, found the Abu Ayyub al-Ansari’s previously unknown tomb. A mausoleum and mosque were established and the site firmly became part of Ottoman foundational lore.1 The current mosque is that built after a devastating earthquake in the eighteenth century (Figures 16 and 17), although much of the time decoration on the mausoleum consists of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century pieces (Figures 18 and 19).

Figure 15: View over Golden Horn and Eyüp from Pierre Loti Cafe (P. Blessing)

Figure 16: View of Eyüp Sultan Mosque, with graveyard in the foreground (P. Blessing)

Figure 17: Courtyard, Eyüp Sultan Mosque (P. Blessing)

Figures 18 and 19: tiles on façade of mausoleum, Eyüp Sultan Mosque (P. Blessing)

Turning away from Eyüp and the Golden Horn, moving along the shore towards Eminönü, the neighborhoods of Fener and Balat are the most recent sites of the gentrification that has already taken over areas such as Beyoğlu and Cihangir in the last twenty years. Yet here, towering above neighborhoods full of historical buildings—some restored, others in ruins—is the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, a poignant reminder of the city’s history but also its present that is not just Turkish and Islamic (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Balat, view up the hill with Patriarchate at the top (P. Blessing)

1. For the details of various sources on these accounts and the early architectural history of the site, see: Kafescioglu, Constantinopolis/ Istanbul, pp. 45-52.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top