-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Spanish Itineraries Part 2: Madrid, Toledo, Zaragoza

With this month’s blog post, I am back in Spain, this time in Madrid and the surrounding areas. While in Toledo and Zaragoza, Islamic monuments are part of the discussion, I will generally also focus on the museums that I visited in all three cities although of course, given especially the large number of such institutions in Madrid, this will not be a complete account.

In Madrid, the central railway station at Puerta de Atocha quickly became a focal point, as high-speed trains are an easy way to travel around the country. The old station building with its courtyard full of plants (Figures 1 and 2) is particularly attractive, even though the platforms are actually in a new annex building. The way from Madrid to Zaragoza leads eastwards, through landscapes dominated by agriculture and small towns.

Figures 1 and 2: Puerta de Atocha railway station, Madrid (P. Blessing)

Once arrived in Zaragoza, nothing around the modern train station betrays the view to come: only minutes away, surrounded by apartment buildings likely built in the 1960s and 1970s, is the Aljafería (Figure 3). The palace was built during the Taifa period (after the downfall of the Umayyad caliphate in Spain) by the local Islamic ruler, Ahmad I ibn Sulayman Sayf al-Dawla Imad al-Dawla al-Muqtadir (r. 1049–82). The building now serves as the regional parliament of Aragon. The exterior, with its fortified aspect, does not point to the interior with its garden courtyard, arches, and stucco decoration (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3: Aljafería, Zaragoza, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 4: Aljafería, Zaragoza, courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 5: Aljafería, Zaragoza, view through arcades at south side of the courtyard (P. Blessing)

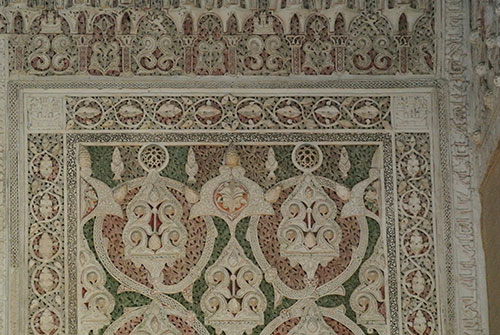

In the interior, the structure strongly evokes the architecture of Umayyad Cordoba, and especially of the palace city of Madinat al-Zahra: gardens, intersecting arches, stucco with vegetal and geometric motives abound (Figures 6 and 7). The mosque of the Aljafería, a small room to the side of a large hall used for receptions and gatherings, contains references to the Great Mosque of Cordoba in details of the decoration, and in the deep niche of the miḥrāb that forms a small room on its own (Figures 8 and 9). Theses references, at the core of a fortified complex reflect the context of a period in which aspirations to the Umayyad caliphate ran high, and conflicts between local rulers forced the construction of strong walls.

Figures 6 and 7: Details of stucco decoration, Aljafería, Zaragoza (P. Blessing)

Figures 8 and 9: Mosque and miḥrāb, Aljafería, Zaragoza (P. Blessing)

In Toledo, reference to Cordoba are present in an earlier monument, the Bab Mardum Mosque, built in 999, and rededicated as the church of El Cristo de la Luz after the Reconquista of the city in 1085 (Figures 10 and 11). The entrance section of the building consists of the original mosque, a small building with each bays, each covered with a different cross-ribbed vault (Figure 12). An extension was added to the eastern end of the mosque to create the church; wall paintings adorn the apse (Figure 13 and 14), and were added the late twelfth thirteenth century, notably showing inscriptions expression blessings in Arabic.

Figures 10 and 11: Exterior views, Bab Mardum Mosque/ El Cristo de la Luz, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figure 12: Vaults of mosque section, Bab Mardum Mosque/ El Cristo de la Luz, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figures 13 and 14: details of wall paintings apse, Bab Mardum Mosque/ El Cristo de la Luz, Toledo, during restoration in March 2014 (P. Blessing)

In style, the paintings are similar to those in the church of San Román in Toledo, built in the early thirteenth century (Figures 15 and 16). The church contains a large collection of Visigothic art, comparable to that in the National Museum of Archaeology in Madrid (on which more later). The church and museum reopened in 2015, and the objects on view present a detailed overview of the early medieval archaeological heritage of the region (Figure 17).

Figures 15 and 16: Interior views, San Román, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figure 17: Detail of display, San Román, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Moving further through the historical center of Toledo, the cathedral (Figure 18) dominates a large section. Built in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, with some later additions, it is one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in Spain, next to the one in Seville. The cathedral is the church of the archbishop of Toledo, the primate of Spain. Burials of the archbishops, some dating to the nineteenth century are located in the cathedral and several of the later ones are marked by cardinals’ hats suspended above them (Figure 19). This is a striking detail that I have not encountered elsewhere, and I have not found background about it so far. Also striking are the foliate arches in the triphorium of the apse (Figure 20), a clear connection to locally engrained forms seen in the Bab Mardum Mosque and Toledo’s Romanesque churches.

Figure 18: Cathedral, Toledo, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 19: Cardinal’s hat suspended above burial of Cardinal Juan de la Cruz Ignacio Moreno y Maisanove (d. 1884), archbishop of Toledo (1875–1884) in Toledo cathedral (P. Blessing)

Figure 20: Detail of triphorium in apse, cathedral, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Not far from the cathedral are two buildings that originally served as synagogues, later as churches, and are now accessible as museums testifying to the Sephardic Jewish heritage of Spain. Santa Maria la Blanca (Figures 21 and 22) was built in the late twelfth century and reconstructed after a fire in 1250; the building became a church in the late fourteenth century.

Figures 21 and 22: Interior views, Santa Maria la Blanca, Toledo (P. Blessing)

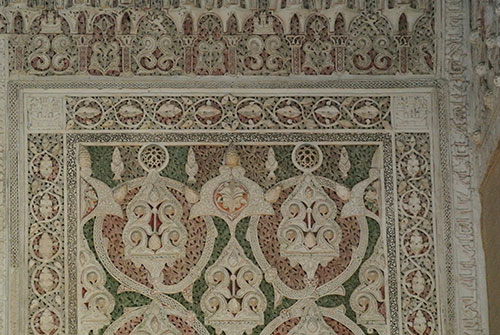

The synagogue of Samuel Ha-Levi, a councilor and treasurer at the court of Pedro I (the Cruel) of Aragon, was completed in 1357 and connected to the patron’s palace (no longer extant). The synagogue was turned into the church after the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492; first known as San Benito, the church’s dedication was to El Transito by the seventeenth century. The decoration of the monument (Figures 23 and 24) evokes that of the Alhambra, and is part of the Mudéjar style that was used in large parts of Spain in the fourteenth and fifteenth century, including the Alcazar of Seville and chapels added to the Great Mosque of Cordoba after its conversion to a church.

Figures 23 and 24: Details of interior stucco decoration, Synagogue of Samuel Ha-Levi, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Leaving Toledo, the train station itself is a striking sight (Figures 25 and 26). Built in 1917–1920, it is an example of Islamic revival architecture. (Readers may remember the city hall of Sarajevo from my August 2015 blog). Architect Narciso Clavería y Palacios was joined in the interior design and details of decoration by local master craftsmen Angel Pedraza, responsible for the tiles, and Julio Pascual Martínez who created metal work (Figures 27 and 28).

Figures 25 and 26: Views of main train station, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figures 27 and 28: Interior, main train station, Toledo (P. Blessing)

The high-speed train takes travellers to Madrid in just 30 minutes, back to Puerta de Atocha station. This would be a place to close, yet I promised a glimpse at Madrid and so here it is with an account of the Museo Arqueológico Nacional (MAN, National Archaeological Museum), reopened in spring 2014 after a major overhaul of its exhibition spaces. Extending over three floors in two connected section, the exhibition begins with pre-historic artifacts and ends with eighteenth-century objects. Even though the focus is largely on Spain, the museum also as a sequence of rooms dedicated to Pharaonic Egypt and the ancient Near East. In the parts dedicated to the history and archaeology, the Roman period and the Middle Ages are particularly strong. A carefully choreographed transition leads from Roman to late antique, Visigothic, and Umayyad all on one floor. Highlights of this section are mosaics (Figure 29), the Visigothic votive crowns found in Guarrazar near Toledo (Figure 30), and a model of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, suspended above the section presenting Umayyad architectural sculpture (Figure 31 and 32).

Figure 29: View of room with fourth- to fifth-century mosaics, MAN Madrid (P. Blessing).

Figure 30: Detail of votive crown of king Recceswinth I (r. 649–672) from the treasure of Guarrazar, MAN Madrid; part of the treasure is in Madrid (MAN and Royal Palace), and other pieces are in the Musée national du Moyen Age, Termes de Cluny in Paris. (P. Blessing)

Figures 31 and 32: Model of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, MAN Madrid (P.Blessing)

Even though the cut off after the Umayyad period to move on to Romanesque and Gothic Iberia on the floor above—and thus squarely into the realm of the Reconquista—gives room to pause, the presentation works remarkably well. It emphasizes the transitions from Roman to late antique Iberia, a world to which the Visigoths and, to some extent, the Umayyads belonged. The question remains whether Umayyad Spain was indeed a part of this late antique Mediterranean world throughout or whether, at least by the tenth century, it had rather absorbed to a large extent the cultural sphere of the Abbasid empire.

Recommended books:

Anderson, Glaire D. The Islamic Villa in Early Medieval Iberia: Architecture and Court Culture in Umayyad Córdoba (Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013).

Nickson, Tom. Toledo Cathedral: Building Histories in Medieval Castile (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015).

Robinson, Cynthia. In Praise of Song: the Making of Courtly Culture in al-Andalus and Provence, 1065-1135 A.D. (Leiden: Brill, 2002).

In Madrid, the central railway station at Puerta de Atocha quickly became a focal point, as high-speed trains are an easy way to travel around the country. The old station building with its courtyard full of plants (Figures 1 and 2) is particularly attractive, even though the platforms are actually in a new annex building. The way from Madrid to Zaragoza leads eastwards, through landscapes dominated by agriculture and small towns.

Figures 1 and 2: Puerta de Atocha railway station, Madrid (P. Blessing)

Once arrived in Zaragoza, nothing around the modern train station betrays the view to come: only minutes away, surrounded by apartment buildings likely built in the 1960s and 1970s, is the Aljafería (Figure 3). The palace was built during the Taifa period (after the downfall of the Umayyad caliphate in Spain) by the local Islamic ruler, Ahmad I ibn Sulayman Sayf al-Dawla Imad al-Dawla al-Muqtadir (r. 1049–82). The building now serves as the regional parliament of Aragon. The exterior, with its fortified aspect, does not point to the interior with its garden courtyard, arches, and stucco decoration (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3: Aljafería, Zaragoza, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 4: Aljafería, Zaragoza, courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 5: Aljafería, Zaragoza, view through arcades at south side of the courtyard (P. Blessing)

In the interior, the structure strongly evokes the architecture of Umayyad Cordoba, and especially of the palace city of Madinat al-Zahra: gardens, intersecting arches, stucco with vegetal and geometric motives abound (Figures 6 and 7). The mosque of the Aljafería, a small room to the side of a large hall used for receptions and gatherings, contains references to the Great Mosque of Cordoba in details of the decoration, and in the deep niche of the miḥrāb that forms a small room on its own (Figures 8 and 9). Theses references, at the core of a fortified complex reflect the context of a period in which aspirations to the Umayyad caliphate ran high, and conflicts between local rulers forced the construction of strong walls.

Figures 6 and 7: Details of stucco decoration, Aljafería, Zaragoza (P. Blessing)

Figures 8 and 9: Mosque and miḥrāb, Aljafería, Zaragoza (P. Blessing)

In Toledo, reference to Cordoba are present in an earlier monument, the Bab Mardum Mosque, built in 999, and rededicated as the church of El Cristo de la Luz after the Reconquista of the city in 1085 (Figures 10 and 11). The entrance section of the building consists of the original mosque, a small building with each bays, each covered with a different cross-ribbed vault (Figure 12). An extension was added to the eastern end of the mosque to create the church; wall paintings adorn the apse (Figure 13 and 14), and were added the late twelfth thirteenth century, notably showing inscriptions expression blessings in Arabic.

Figures 10 and 11: Exterior views, Bab Mardum Mosque/ El Cristo de la Luz, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figure 12: Vaults of mosque section, Bab Mardum Mosque/ El Cristo de la Luz, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figures 13 and 14: details of wall paintings apse, Bab Mardum Mosque/ El Cristo de la Luz, Toledo, during restoration in March 2014 (P. Blessing)

In style, the paintings are similar to those in the church of San Román in Toledo, built in the early thirteenth century (Figures 15 and 16). The church contains a large collection of Visigothic art, comparable to that in the National Museum of Archaeology in Madrid (on which more later). The church and museum reopened in 2015, and the objects on view present a detailed overview of the early medieval archaeological heritage of the region (Figure 17).

Figures 15 and 16: Interior views, San Román, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figure 17: Detail of display, San Román, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Moving further through the historical center of Toledo, the cathedral (Figure 18) dominates a large section. Built in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, with some later additions, it is one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in Spain, next to the one in Seville. The cathedral is the church of the archbishop of Toledo, the primate of Spain. Burials of the archbishops, some dating to the nineteenth century are located in the cathedral and several of the later ones are marked by cardinals’ hats suspended above them (Figure 19). This is a striking detail that I have not encountered elsewhere, and I have not found background about it so far. Also striking are the foliate arches in the triphorium of the apse (Figure 20), a clear connection to locally engrained forms seen in the Bab Mardum Mosque and Toledo’s Romanesque churches.

Figure 18: Cathedral, Toledo, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 19: Cardinal’s hat suspended above burial of Cardinal Juan de la Cruz Ignacio Moreno y Maisanove (d. 1884), archbishop of Toledo (1875–1884) in Toledo cathedral (P. Blessing)

Figure 20: Detail of triphorium in apse, cathedral, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Not far from the cathedral are two buildings that originally served as synagogues, later as churches, and are now accessible as museums testifying to the Sephardic Jewish heritage of Spain. Santa Maria la Blanca (Figures 21 and 22) was built in the late twelfth century and reconstructed after a fire in 1250; the building became a church in the late fourteenth century.

Figures 21 and 22: Interior views, Santa Maria la Blanca, Toledo (P. Blessing)

The synagogue of Samuel Ha-Levi, a councilor and treasurer at the court of Pedro I (the Cruel) of Aragon, was completed in 1357 and connected to the patron’s palace (no longer extant). The synagogue was turned into the church after the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492; first known as San Benito, the church’s dedication was to El Transito by the seventeenth century. The decoration of the monument (Figures 23 and 24) evokes that of the Alhambra, and is part of the Mudéjar style that was used in large parts of Spain in the fourteenth and fifteenth century, including the Alcazar of Seville and chapels added to the Great Mosque of Cordoba after its conversion to a church.

Figures 23 and 24: Details of interior stucco decoration, Synagogue of Samuel Ha-Levi, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Leaving Toledo, the train station itself is a striking sight (Figures 25 and 26). Built in 1917–1920, it is an example of Islamic revival architecture. (Readers may remember the city hall of Sarajevo from my August 2015 blog). Architect Narciso Clavería y Palacios was joined in the interior design and details of decoration by local master craftsmen Angel Pedraza, responsible for the tiles, and Julio Pascual Martínez who created metal work (Figures 27 and 28).

Figures 25 and 26: Views of main train station, Toledo (P. Blessing)

Figures 27 and 28: Interior, main train station, Toledo (P. Blessing)

The high-speed train takes travellers to Madrid in just 30 minutes, back to Puerta de Atocha station. This would be a place to close, yet I promised a glimpse at Madrid and so here it is with an account of the Museo Arqueológico Nacional (MAN, National Archaeological Museum), reopened in spring 2014 after a major overhaul of its exhibition spaces. Extending over three floors in two connected section, the exhibition begins with pre-historic artifacts and ends with eighteenth-century objects. Even though the focus is largely on Spain, the museum also as a sequence of rooms dedicated to Pharaonic Egypt and the ancient Near East. In the parts dedicated to the history and archaeology, the Roman period and the Middle Ages are particularly strong. A carefully choreographed transition leads from Roman to late antique, Visigothic, and Umayyad all on one floor. Highlights of this section are mosaics (Figure 29), the Visigothic votive crowns found in Guarrazar near Toledo (Figure 30), and a model of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, suspended above the section presenting Umayyad architectural sculpture (Figure 31 and 32).

Figure 29: View of room with fourth- to fifth-century mosaics, MAN Madrid (P. Blessing).

Figure 30: Detail of votive crown of king Recceswinth I (r. 649–672) from the treasure of Guarrazar, MAN Madrid; part of the treasure is in Madrid (MAN and Royal Palace), and other pieces are in the Musée national du Moyen Age, Termes de Cluny in Paris. (P. Blessing)

Figures 31 and 32: Model of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, MAN Madrid (P.Blessing)

Even though the cut off after the Umayyad period to move on to Romanesque and Gothic Iberia on the floor above—and thus squarely into the realm of the Reconquista—gives room to pause, the presentation works remarkably well. It emphasizes the transitions from Roman to late antique Iberia, a world to which the Visigoths and, to some extent, the Umayyads belonged. The question remains whether Umayyad Spain was indeed a part of this late antique Mediterranean world throughout or whether, at least by the tenth century, it had rather absorbed to a large extent the cultural sphere of the Abbasid empire.

Recommended books:

Anderson, Glaire D. The Islamic Villa in Early Medieval Iberia: Architecture and Court Culture in Umayyad Córdoba (Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013).

Nickson, Tom. Toledo Cathedral: Building Histories in Medieval Castile (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015).

Robinson, Cynthia. In Praise of Song: the Making of Courtly Culture in al-Andalus and Provence, 1065-1135 A.D. (Leiden: Brill, 2002).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top