-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Reclaimed: Sites of Conflict, Industry and Population Change in Japan

Danielle S. Willkens is the 2015 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Spring is beginning to make an appearance in Japan. Although the evenings are still cool in central Honshu, the days are getting warmer and some of the sakura [cherry blossoms] are blooming, complementing the deep purple flowers of the plum trees that signify the end of winter. This month, my travels have taken me to islands within the Seto Inland Sea, sites along Osaka Bay, and southern cities in the island of Kyushu. Although I’m fully taking advantage of the incredible public transportation systems in Japan, walking a half-marathon has become a daily occurrence. To fully absorb the scale and organization of a city, I found that walking between architectural sites, museums, and gardens is the best. Walking provides serendipitous opportunities for discovery: an interesting alleyway, an Edo-era merchant house tucked between contemporary, low-rise residential buildings, or the chance to observe the quotidian elements of a place such as the distinctive metal covers for each city’s water, sewer, and power access (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A collage of Japan’s creative metal covers for elements of urban infrastructure.

This month I have been able to explore several projects by some of Japan’s most famous, contemporary architects: Tadao Ando (b.1941), Akira Kuryu (b.1947), Kengo Kuma (b.1954), Hiroshi Sembuichi (b.1968), and SANAA [partners Kazuyo Sejima (b.1956) and Ryue Nishizawa (b.1966)]. With a wealth of projects in the nation, I decided to focus my work on their museums and other tourist-centric sites; thankfully, this also allowed for an aligned study of projects with unique material applications and ambitious environmental performance qualities (Figures 2-4).

Figures 2-4. As one of the first structures built next to the Kobe harbor following the devastating earthquake in 1995, Ando’s Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of Art (2002) features a large urban plaza and several outdoor rooms.

After spending a few weeks exploring impeccably detailed concrete buildings and structures that interlace the built and natural environments through the use of performative screens and passive strategies for environmental conditioning, I discovered that many projects from the last few decades very successfully respond to the celebrated heritage of adjacent sites and, consequently, enhance the visitor’s experience. For example, the sloping elements of Ando’s Museum of Literature (1991; annex 1996) in Himeji serve as a bridge between a library, museum, and a preserved bokeitei [traditional home] while the concrete promontory and open structural frames direct views to the mountains and towards the city’s most iconic architectural site: the Himeji Castle (Figures 5-7).

Figures 5–7. Views of Ando’s Museum of Literature in Himeji.

Of the more than 3,000 castles that once dominated the Japan’s mountainous landscape, only twelve authentic tenshu [main towers or keeps] remain (Figures 8 and 9).1 A majority of these castles were lost during the Azuchi-Momoyama (1575–1600) and Edo (1603–1876) periods, destroyed by natural disasters or purposeful dismantlement to prevent rival daimiyō from mounting an attack on the ruling government. Castle numbers dwindled further in the modern era due to the cost of maintenance and lack of interest in preserving remnants of the samurai past.2 Grassroots efforts in the early 20th century saved several structures but others perished amid the bombings of World War II (Figures 8–10).

Figure 8. A view of Matsumoto Castle (1590–1614) in Nagano Prefecture. Threatened by destruction, the local townspeople purchased the castle in 1877 and funded the first major restoration in 1913.

Figure 9. A view of the tsukimi-yagura [moon viewing room] at Matsumoto Castle.

Figure 10. A view of one of the castle’s shachihoko, a mythical creature with the head of a tiger and the body of a fish. Its upturned posture at the end of the gable signified the creature expelling water and thereby protecting the castle from fire.

Reclaiming a significant element of the nation’s built heritage, the Japanese government championed the preservation of extant castles by sponsoring the reconstruction of several fortified sites and even working to elevate one site, Himeji Castle (1577–1602), to UNESCO World Heritage Status (Figures 11 and 12). Located in a strategic location between western Japan and central Honshu, Himeji is the best-preserved castle from the 17th century and visitors arriving to the city by train are immediately presented with a striking view of the fortification: the station was designed on axis with the castle. Although smaller projects were initiated in the 1930s, the castle’s first major restoration occurred between 1956 and 1964, during the Shōwa Era, and another was completed between 2009 and 2015. The most recent project proved that a substantial restoration must be undertaken every fifty years to ensure the integrity of the castle’s walls, roof, and earthen embankments. Although the nation purposefully destroyed castles in the early 20th century, both local and national agencies are now dedicated to the preservation of this building type. Additionally, there is a growing tourist infrastructure around castle sites that typically includes museums, reinvented sōgamae [outer enclosure] and guruwa [bailey] with souvenir shops and food trucks, and even costumed samurai wandering the grounds to take photographs with visitors.

Figure 11. After World War II, several castles were reconstructed in concrete. From left to right: Osaka Castle (1583; demolished 1868; reconstructed 1931–1953), Okayama Castle (c.1590; demolished 1945; reconstructed 1965), and Hiroshima Castle (1591; abandoned 1874; demolished 1945; reconstructed 1957).

Figures 12 and 13. Views of the Himeji Castle and its interior, comprised of substantial wooden structural members.

In addition to reclaiming defensive architecture of the Warring States and Edo periods, Japan is actively promoting sites associated with industrial development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Located mainly near coastal sites, intensive research and restoration projects for several industrial heritage sites began in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Despite an unsuccessful application to the World Heritage Tentative List in 2007, a consortium effectively pursued listing again in 2009 and in 2015 twenty-three sites were elevated to the UNESCO World Heritage List status as a thematic group: Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining. The consortium produced an incredible record of maps, diagrams, and research articles, promoting visits to the associated sites through group tour programs and a rich website. During my mid-afternoon, weekday visit to the Nirayama Reverberatory Furnaces (1857), more than five buses disembarked at the small site. However, few visitors made the extra trek to see the preserved residence of Hidetatsu Egawa, located near the Nirayama Furukawa River.

Much like the everyday life around a castle from the 15th to the mid-19th century, many of the sites associated with Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution focused on the construction of defensive structures and the fabrication of weapons; only the methods, tools, and scale changed. Further connecting warring sites in Japan’s pre-modern and modern eras, are yuru-chara. These cartoonish mascots appear at the majority of Japan’s tourist sites, providing photo opportunities for playful shots with costumed characters and elevating souvenir sales. For example, the industrial site of the Nirayama Reverberatory Furnaces was transformed into an endearing character, with the towers as the body and a canon for a nose (Figure 14).

Figure 14. A collage of various mascots, ranging from a granite sculpture ‘Takamaru-kun’, the hawk-castle of Hirosaki (far left) and Tokyo SkyTree character (far right), to cartoons of mascots (clockwise from top left) for Shimane Prefecture, Nirayama Reverberatory Furnace. Hikone, Himeji Caslte, Kyoto Tower, and the Edo-Tokyo Museum.

While exploring projects by contemporary architects and World Heritage Sites, another theme emerged within examples of Japan’s architectural landscape: tourism as a way to reclaim and reinterpret the past while ensuring the preservation of certain sites in peril. In the 1990s, tourism in Japan was dominated by travel to theme parks, such as Tokyo Disneyland. But initiatives of the 2000s are ushering in some different tourist destinations: new buildings are framing Japan’s heritage, and architectural contributions, in imaginative ways while other sites are wrestling with some of the most challenging elements of the nation’s history. This month’s post will analyze several, disparate examples of Japan’s ‘reclaimed’ built heritage, ranging from sites that memorialize the impacts of a global war to those that celebrate industry and reveal the changing demographics of the nation.

Paper Cranes and Battleships

While in the process of brainstorming themes and associated sites for my application to the SAH Brooks Travelling Fellowship, I contemplated looking at contested sites: places that experienced feverous debates between the case for preservation versus the need for destruction. Within the list of potential destinations was the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial and the Genbaku [Atomic Bomb] Dome (Figures 15 and 16). As one of the only structures to survive the bomb, the Genbaku Dome was original designed by Jan Letzel as the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall (1915). After decades of ‘preserve or destroy’ debates following the initial preservation resolution of 1966, the Genbaku Dome was designated a World Heritage Site in 1996 and the site is labeled as an example of ‘conservation for peace.’

Figures 15 and 16. Views of the Genbaku Dome, located only 160 meters from the hypocenter. The project recently underwent structural conservation to mitigate damage from a possible earthquake.

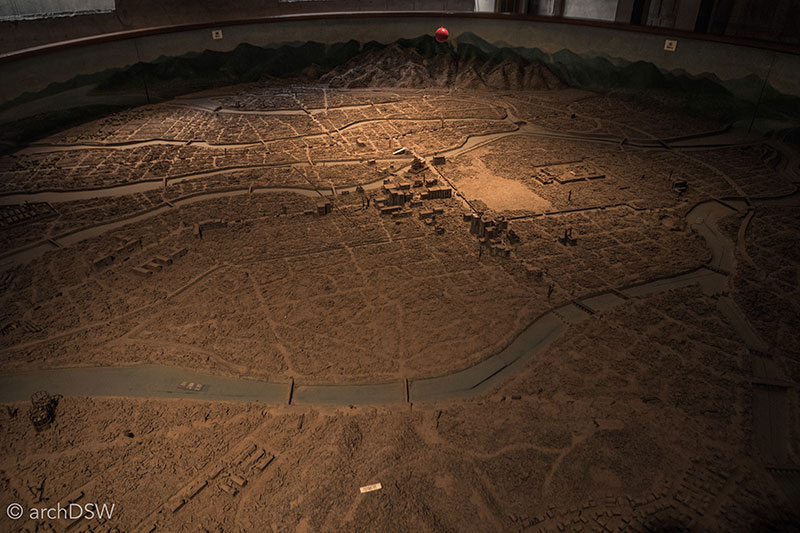

There were an estimated 350,000 people in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb “Little Boy” detonated at 8:15 am on August 6, 1945 (Figure 17). The hypocenter was near the Nakajima district; a densely populated and active island filled with Edo era buildings, located in the heart of downtown Hiroshima between the Motoyasu-gawa and Honkawa Rivers. The built features of this area made the Nakajima district the primary target: a set of distinctive wooden bridges and the T-shaped Aioi-bashi Bridge made an H-shaped formation at the northern end of this island. A site in the former Nakajima district was selected for a memorial and museum, to educate visitors about the impacts of nuclear war. Kenzo Tange (1913–2005) was commissioned to complete the project and the Hiroshima Peace Center and Memorial Park (1955) represented his first large-scale urban commission (Figures 18 and 19). The East Building of the museum is currently undergoing a substantial renovation and exhibit redesign as part of a comprehensive renovation project scheduled for completion in summer 2018. The noise from hammers and mechanical equipment provided the only soundscape for the Peace Memorial Park (Figures 20–22). It was, largely, a silent public space: a group of adolescent Japanese students quietly placed a chain of paper cranes at the Children's Memorial while others made their way from the museum to the Genbaku Dome.

Figure 17. A large-scale model in the Peace Museum illustrates the immediate destruction to the built environment.

Figures 18 and 19. The reinforced concrete structure and use of both piloti and beton brut at the Peace Museum reflect the influence of Le Corbusier’s work on Tange’s postwar architecture.

Figure 20. The Memorial Cenotaph (1952) in the Peace Memorial Park frames views between the Peace Museum and the Genbaku Dome.

Figure 21 and 22. Designed by Kazuo Kikuchi and Kiyoshi Ikbe for the grounds of the Peace Memorial Park, the Children’s Peace Monument (1958) memorializes the life of Sadako Sasaki (1943–1955). Sadako was a hibakusha, a person affected by the bomb, since exposure to radiation at age two eventually triggered Leukemia in her pre-teen years. Determined to beat the disease, she undertook a project to fold 1,000 paper cranes, a symbol of peace. In memory of Sadako and other children who were victims, visitors leave paper cranes in the protected acetate niches of the memorial.

Although the reconstructed castle, several parks, and religious sites in Hiroshima are popular tourist destinations, the city is dominated by ‘peace’ tourism. The train station and select sites provide walking tour maps of sites associated with the fallout of the atomic bomb and these associated sites charge a modest entry fee while others are free. Although the Peace Memorial Park, Museum and Genbaku Dome have been established memorial sites for more than fifty years, a few sites have recently undergone renovations and they serve as lesser known building-fragments-as-memorials and Peace Museums with rotating exhibits and artistic installations (Figures 23–26).

Figure 23. The stone façade of the Former Bank of Japan, Hiroshima Branch (1936) withstood the blast. Since the bomb detonated in the early morning hours, the bank was not yet open and the iron shutters were closed on the first and second floors, protecting the interior. The third floor, however, was largely destroyed. The integrity of the structure allowed banking operations to resume two days after the bombing and since the mid-1990s the building has been a cultural site for exhibitions and lectures.

Both the Fukuro-machi Elementary School (b.1872) and the Honkawa Elementary School (founded 1873; 1928 wing) were made of ferro-concrete and although heavily damaged in the blast, classes resumed in the portions of the buildings’ shells by the spring of 1946. Today, these small Peace Museums are both surrounded by active schools and at the Honkawa Elementary School visitors use a buzzer at the school's side gate to gain entrance to the registration office. Here, they are issued with visitor's passes and instructed to walk towards the small, one-story concrete structure, essentially a preserved corner of the former school, to enter the Peace Museum.

Figure 24. The ferro-concrete West Wing (1973) of the Fukuro-machi Elementary School survived the bomb and served as a first aid station and shelter for locals. Although the majority of students had been evacuated to four neighboring villages by April 1945, several teachers and approximately 100 students were in the school at the time of the bombing. During the 2002 restoration, the removal of layers of plaster revealed messages on old blackboards and in char along the walls of the stairs, hallways, and preserved classroom. A structural stabilization project from this restoration also revealed that the radiation from the blast carbonized the wooden blocking in the school’s walls.

Figures 25 and 26. The Honkawa Elementary School was Hiroshima’s first three-story ferro-concrete building and although it could hold nearly 1,000 students, the spring evacuations left only 400 students in the building at the time of the bomb. The site was designated a Peace City Memorial School by the Ministry of Education in 1950 and a new school was built in 1988, preserving a portion of the 1928 building as a museum.

One might think that Nagasaki, a city destroyed by an atomic bomb three days after Hiroshima, would have similar elements to Hiroshima. However, the overall layout, geography, and approach to interpretation at Nagasaki are palpably different from Hiroshima, as well as other Japanese cities. Streetcar lines crisscrossed cobblestone streets and passed over layered canal embankments (Figure 27). Western-style buildings and Christian churches, with neo-Gothic and neo-Romanesque forms, line steep and winding streets by the harbor, their landscapes enlivened with the early blossoms of colorful wildflowers and swaying palm trees (Figures 28 and 29). Throughout the downtown, there are several, bold, commercial and residential examples of postmodernism and these are inherently intriguing structures since Japan was introduced to classicism in the late 19th century. During the Meiji period (1868–1912), the nation was introduced to the professionalization of architecture while it negotiated challenges to traditional practices in building form and production as well as the rapid changes associated with the industrial revolution, ushering in a host of new technologies and building typologies.

Figure 27. A view of the streetcar network near the famous stone ‘Spectacles Bridge’ spanning Nagasaki’s canal.

Figure 28. A gatehouse in Glover Garden, a residential district influenced by Scottish merchant Thomas Blake Glover who played a key role in the development of Nagasaki’s harbor and trade infrastructure in the late 19th century.

Figure 29. Oura Catholic Church (1865) survived the atomic bomb and the adjacent structures, once a seminary and residence for missionaries, represent architectural hybrids akin to a Japanese-Charlestonian style.

As a city dominated by the harbor, Nagasaki was home to the only international trade during the period of sakoku, Japan's self-imposed isolation from c.1639 to 1853. Nagasaki's early identification as the 'foreigner's city' of Japan was reinforced during my visit since the streets around the harbor were flooded with Australian and European tourists enjoying a shore break from the Queen Mary 2. The active and extensive harbor makes the city receptive to cruise ships, allowing visitors to see sites associated with the industrial revolution, international exchange, and the second atomic bomb (Figures 30 and 31).

Figure 30. Design by Akira Kuryu, National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims (2002) commemorates the lives of the estimated 70,000 who perished instantly when the bomb exploded at 11:02 am on August 9, 1945. In the Remembrance Hall, twelve luminescent, glazed pillars frame a view of the memorial column, holding the names of all identified victims. Beyond, the columnar axis positions viewers towards the bomb's hypocenter.

Figure 31. The pool and gentle cascades of water at the memorial site recall the intense thirst that bombing victims experienced after the blast. At night a field of fiber optics illuminates the pool, as seen here on the architect’s website. From certain angles, the pool reflects the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum (1996) and the Noguchi Taro Fine Arts Museum.

The Nagasaki Prefecture has nearly 1,000 islands; however, not all of these islands are quaint sites for fishing, swimming, or leisurely repose. Several islands were rough sites centered around industrial production, such as coal mining on Takashima and Hashima. Both islands were submarine coalmines: Takashima was the Mitsubishi Mining Company's main coalmine but Hashima, familiarly known as Gunkanjima [battleship island], has become more famous because of its architecture, engineering innovations, and complex history (Video 1 and Figure 32).3 Coal was discovered on Gunkanjima in 1810 and a mine was opened sixty years later. In 1890, the Mitsubishi Company purchased the mine and during nearly a decade of operations the submarine coalmine grew to include five shafts (1887, 1895, 1896, 1925, 1965) and ten tunnels, reaching depths of 1010 m below sea level. Although the main mountain and submarine mine form the core of the island, the habitable landscapes of Gunkanjima were largely manmade: the island was enlarged six times between 1893 and 1931 and these extensions tripled the original size of the island. Between its opening in 1891 and closure on January 15, 1974, it is estimated that more than 15.7 million tons of coal were excavated on the island.4

Video 1. Scenes from the passenger boat to Gunkanjima.

Figure 32. From this perspective is becomes clear how Hashima earned its nickname Gunkanjima [battleship island] since the densely-inhabited constructed concrete island has a distinctive ‘bow’ and protruding towers akin to a warship.

With arduous shift work and difficult conditions, miners received higher wages than the average Japanese worker and were, thus, willing to live on an isolated site, sharing only one telephone line for the entire complex and subsisting on strict fresh water rations. Although there were numerous operational restrictions on the island, it was also a site for innovations in architecture and engineering. The seawall protecting the site from typhoon damage was one of the most fortified in Japan and the built environment used space effectively. In 1960 when the island’s population peaked at 5,300 inhabitants, the island was the most densely populated in all of Japan. With limited space, building rooftops were used as playgrounds and reinvented as some of Japan’s earliest green roofs with plots for vegetable gardens. Natural light, too, was precious on the dense, urbanized island so the building program prioritized light and view for the residential buildings and school while placing commercial and service spaces, such as grocery stores, pachinko halls, communal baths in the lower levels and basements of buildings. Only senior officials for the mining company had private bathing facilities in their residences so the island had a network of public baths that used boiled seawater. Due to the coal dust, the miners had their own two-stage bathing complex: after exiting one of the two-story steel transportation cages in the mine, they would first submerge themselves fully in their uniforms before proceeding to a ‘clean’ bath.

Not counting the ruinous structures related to the mine, the island has seventy-one crumbling buildings, built between 1916 and 1970 (Figures 33–36). The seven-story building labeled no. 30 on the island, known as ‘Glover’s House’ (1916), was Japan's first reinforced concrete apartment block. With a central courtyard to bring light to the inner apartments, this building was home to over 700 residents at one point and families shared cramped quarters in their 6-tatami mat apartments. With a growing population in the early 20th century, an elementary school opened in 1934 and a larger, seven-story building was constructed in 1958 (no. 70) to accommodate an elementary school and junior high as well as auxiliary spaces such as a library and auditorium. The two-story addition (no.71, built 1970) to this building was the last structure built on the island and it included a gymnasium as well as the only elevator on the island.

Figure 33. A view of building no. 30, ‘Glover’s House’, from the final viewing platform on the island.

Figure 34 and 35. Views of the island’s crumbing elementary and junior high schools

Figure 36. These trabeated concrete forms are the remnants of the coal storage area's conveyor belt.

Featured in Skyfall (2012) as the villain’s liar within a decaying, dystopian landscape, Gunkanjima was opened to tourists in 2009. With goals to raise awareness about the history of the island and generate revenue to initiate preservation projects, a handful of companies were given authorization to access the island through an advanced reservation system. Unpredictable, rough weather frequently cancels tours and those lucky enough to secure a successful tour are limited to a closely monitored experience on the island, relegated to a concrete and steel pathway that parallels the ruins of the original mine buildings on the southern side of the island. Both the tour of the island and the hour-long journey to and from the site are narrated but those wishing to explore the site in greater depth can visit the newly opened and interactive Gunkamjima Digital Museum (2015) near the ferry terminal. As the name implies, the museum uses cutting-edge technology to relay the history of mining on the island and explore the lives of the concrete island’s occupants: using captured footage from a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) and aerial photogrammetry, the team created an accurate digital model. This model, paired with Google Maps Street View footage and panoramic imagery, was also used to generate a virtual reality experience at the museum that allows visitors to 'walk through' portions of the island that are no longer safe or accessible.

Although much of the interpretation on the island focuses on architecture, engineering, invaluable contributions to the Japanese Industrial Revolution, and the spirit of Japanese citizens who thrived in the island’s unusual environment, there are few elements that fully address the darker sides of the island’s history. The lives lost in the precarious mines, accidents related to toxic gases and natural disasters, and the island’s role as a work camp during World War II elicited opposition to the site’s inclusion in the thematic UNESCO World Heritage listing for the Meiji Industrial Revolution. Nonetheless, the site was included.

As a site far from the viewshed of the Nagasaki harbor, Gunkanjima could easily be a ‘forgotten’ heritage site, or one documented only because of its deteriorated state; however, it seems clear that Nagasaki is dedicated to the preservation of the island. Interestingly, with goals for eventual restoration and extended tourism, the site is billed as something more than a ‘bucket list’ attraction: the Gunkanjima Concierge Company, one of the few tourist companies authorized to access the island, offers visitors a free visit to after three trips.

Art Islands

The reclaimed sites discussed thus far focus on urban areas however there is another series of projects in the Seto Inland Sea that cannot be overlooked in this brief analysis of reinvention projects in Japan: the ‘art islands’ of Inujima, Naoshima, and Teshima. Varying in scale and materiality, projects on these islands make use of the built and natural landscapes while addressing the declining population. At each of the site-specific projects, the physical environment plays an integral role, whether through the use topography, the adaptation of historic vernacular structures, or the influence of weather within an unpredictable, coastal climate (Videos 2 and 3).

Video 2. Scenes of rough seas and changing skies from the ferries and passenger boats between Naoshima, Teshima, and Inujima.

Video 3. Scenes from an electric bike on Naoshima.

Naoshima, perhaps the best known of the islands and the most developed in terms of its supporting infrastructure of hotels, hostels, cafes, and transportation options, consists of several projects by Tado Ando: the Benesse House Museum (1992) with several supporting galleries and hospitality structures built in the last decade, the Chichu Art Museum (2004) that contains installation-specific galleries for the work of Claude Monet, James Turrell and Walter De Maria, the Lee Ufan Museum (2010), and the Ando Museum (2013), a gallery that houses the architect’s sketches and models within an adapted wooden home from the early 20th century (Figure 37).5 In addition to the galleries, the island is home to an ever-growing collection of sculptures, installations, and the on-going work of the Art House Project. Initiated in 1998, this project transforms empty homes and deteriorating sites into works of art that emphasize experience and experimentation (Figures 38–43).

Figure 37. Photographs are not permitted in and around the majority of the island’s galleries, however this view showcases the approach to the Lee Ufan Museum that integrates elements of the coastal site, sculptures, and architecture.

Figure 38. A view of Yoyoi Kusama’s Red Pumpkin from the ferry at Naoshima’s Miyanoura Port.

Figure 39. The geometric Naoshima Pavilion (2015), made of steel, was designed by architect Suo Fujimoto as Naoshima’s ‘28th’ uninhabited island.

Figure 40. A fiberglass and wood bicycle pavilion marks Naoshima’s other port, Honmura, and provides a place for visitors to park their rented transportation while visiting the Art House Projects.

Figures 41 and 42. Two structures, the restored Go-o Shrine (c.1338–1573) and Hiroshi Sugimoto’s installation Appropriate Structures (2002), occupy this wooded, hilltop site. A set of thick, stacked glass stairs symbolically connects the material world with the spiritual one.

Figure 43. Some of the island’s inhabitants decorate their homes with their own artistic creations, such as these miniature pumpkins in homage of Kusama’s work.

Although similar in area to Naoshima, the ‘art island’ aspects of Teshima are primarily composed of smaller installations and collaborative projects, such as the special and environmental wonder of the Teshima Art Museum, the Yokoo House, and the Needle Factory (Figure 44). Like sites on Naoshima, the majority of the sites on Teshima prohibit both photography and sketching therefore visitors are fully immersed in the sensory experiences of the installations and repurposed structures. With these conditions in mind, it is easy to imagine how each site changes during different seasons and weather conditions, making the ‘art islands’ perpetually fascinating for both new and repeat visitors.

Figure 44. As a product of architect Ryue Nishizawa and artist Rei Naito, the Teshima Art Museum is a large and lofty concrete shell with an integrated water system that pushes droplets from weep holes in the polished concrete floor. Adjacent to the museum space is a small café and gallery.

As smallest of the art islands, Inujima is, arguably, the best example of the integration of architecture, art, and the environment through the Inujima Seirensho Art Museum (2008) and the Art House Project. The average age of residents on the island is eighty, therefore the projects were intended to revive the site and encourage a new pathway towards a sustainable future on the island known for its local stone and once dominated by a copper refinery.

Designed by Sambuichi, the Seirensho Art Museum utilizes the island’s signature stone and elements of the abandoned Edo era copper refinery, such as the preserved chimneystack and labyrinth of rooms formed by slag bricks (Figures 45–48). Composed of two galleries and two halls, the museum uses natural elements such as sun, wind, and light to manipulate temperatures and views within the building. These systems work with nature, instead of trying to forcefully, and mechanically, control it. Additionally, the changing environmental conditions within the pavilion activate elements of the installation, such as the Yukinori Yanagi’s Hero Dry Cell (2008). This piece suspends deconstructed building fragments from the abandoned home of writer Yukio Mishima’s (1925–1970), a critic of Japan’s industrial modernization and postwar cultural crisis.

Figures 45–48. Views of the low-lying new construction elements and the preserved sections of the Seirensho copper refinery.

Using existing, repurposed, and reinvented homes, the Art House Project was inaugurated by architect Kazuyo Seijima as a way for the island's inhabitants and visitors to have new interactions with the local landscape and vernacular architecture through the incorporation of new materials, pathways, and contemporary art installations. Three homes, with abbreviated names referencing the former owners (F-Art House, S-Art House, and I-Art House, 2010) and a steel pavilion were built on the island in 2010, but the experiment continues to grow with two additional homes (A-Art House and C-Art House, 2013), an installation at the site of a former stonecutter’s house, and a series of impromptu renovation and repurposing projects by locals, whether as new sites for art or small in-home cafes catering to visitors (Figures 49–57).

Figure 49. The deconstructed F-Art House currently houses Biota (2013) by Kohei Nawa.

Figures 50–52. The linear, acrylic gallery of the S-Art House is currently home to an installation called contact lens (2013) by Haruka Kojin that encourages visitors to see the existing built and natural landscapes from new perspectives.

Figure 53. As a circular version of the S-Art House, the A-Art House holds an installation, relfectwo (2013), by Kojin that is reminiscent of the vibrant wildflowers on the island.

Figure 54. The installation Ether (2015) by Chinatsu Shimodaira weaves a series of strings through the timber structure of the C-Art House.

Figure 55. A view of the former site of a stonecutter’s house, with Yusuke Asai’s Listen to the Voices of Yesterday Like the Voices of Ancient Times (2013–2016).

Figures 56-57. In addition to visitors, guides, and a few residents, the island had a number of active builders and gardeners working to develop new sites and productive plots of land.

It should be noted that trips to the art islands require some serious logistical planning and supporting funds. Many of the visitors to the islands were part of organized groups that coordinated ferry schedules, on-island transportation, entrance fees, and other necessities such as food and lodging. Although it is entirely feasible to coordinate visits to Iujima, Naoshima, and Teshima independently, be prepared to spend significant time prior to traveling: create a list of timetables to coordinate train travel to ports with the schedules of ferries or passenger boats. Weather in the Seto Inland Sea can be rough and water traffic prioritizes the local passengers, not tourists, so visitors need to arrive early to ports to purchase the proper tickets and receive numbered boarding cards.

New Sites; New Ruins

Beyond its natural beauty and scenic overlook, Mount Rokkō receives approximately 100,000 visitors a year. Comprised of architectural pilgrimage sites such as Sambuichi’s new Rokkō-Shidare (2010) as well as Ando’s projects at Rokkō Housing (1983; 1993; 1998) and the Chapel on Mount Rokkō (1986), the region is a distinct destination for architectural tourists.6

Figures 58–60. On sunny days, the wooden core of the observatory becomes a surface for the play of shadows from the steel skin. This video, by the architect, illustrates the way the building responds to the harsh winter climate.

Figure 61.The building’s core, designed to use the chimney effect for passive cooling, contains a spiraling entry path leading to an inner chamber.

This does not, however, ensure the ongoing maintenance of projects. Sadly, the hotel that once provided access to Ando’s Chapel, and commissioned the project as an exclusive on-site wedding chapel, has been abandoned and is quickly slipping into disrepair. A series of plastic partitions, chain link fencing and a concrete wall surround the entire complex, preventing access to the chapel (Figure 62). In fact, upon closer inspection and when moving away from prescribed paths and cafes on the mountaintop, it becomes clear that much of Mount Rokkō has been abandoned: the summer homes of Kobe residents, built in the 20th century as a place to escape the heat of summer in the city, are vacant, and several of the area’s hotels, built into the cliffside, are crumbling. As Japan reclaims its built heritage from the era of samurai and the Meiji Industrial Revolution, it will be critical that the sites of the recent past, especially those that helped ignite the careers of contemporary architects, are not forgotten.

Figure 62. One of the only accessible views of the Chapel on Mount Rokkō, as seen through a chain link fence.

Bibliography

Futagawa, Yukio, ed. Tadao Ando Details. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita, 1991.

Hashimoto, Atsuko, and David J. Telfer. "Transformation of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island): From a Coalmine Island to a Modern Industrial Heritage Tourism Site in Japan." Journal of Heritage Tourism 12 (2017): 107-24.

Hatakeyama, Naoya, and Ryūji Miyamoto, eds. Chichu Art Museum: Tadao Ando Builds for Walter De Maria, James Turrell, and Claude Monet. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2005.

Jodidio, Philip. Ando: Complete Works. Köln: Tasche, 2004.

———. Tadao Andō at Naoshima. New York, NY: Rizzoli, 2006.

Marchand, Yves. Gunkanjima. Göttingen: Steidl, 2013.

Mitchelhill, Jennifer. Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty. Edited by David Green Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2003.

Molinari, Luca, ed. Tadao Ando Museums. London: Thames & Hudson, 2009.

Pare, Richard, and Tom Heneghan. The Colours of Light: Tadao Ando Architecture. London: Phaidon, 2000.

"Sambuichi." JA: The Japan Architect 81 (2011).

1 The preserved tenshu are: Bitchu-Matsuyama, Okayama (1575), Hikone, Shiga (1603), Himeji, Hyogo (1580), Hirosaki, Aomori (1611), Inuyama, Aichi (1573), Kochi, Kochi (1601-3), Marugame, Kagawa (1597), Maruoka, Fukui (1576), Matsue, Shimane (1607-11), Matsumoto, Nagano (1590-1614). Matsuyama, Ehime (1602-27), and Uwajima, Ehime (1596).

2 For a well illustrated and much more detailed description of the decline of Japan’s castles, see Jennifer Mitchelhill, Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty, ed. David Green (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2003).

3 See Atsuko Hashimoto and David J. Telfer, "Transformation of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island): From a Coalmine Island to a Modern Industrial Heritage Tourism Site in Japan," Journal of Heritage Tourism 12 (2017); Yves Marchand, Gunkanjima (Göttingen: Steidl, 2013).

5 See Naoya Hatakeyama and Ryūji Miyamoto, eds., Chichu Art Museum: Tadao Ando Builds for Walter De Maria, James Turrell, and Claude Monet (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2005); Philip Jodidio, Ando: Complete Works (Köln: Tasche, 2004); Tadao Andō at Naoshima (New York, NY: Rizzoli, 2006); Luca Molinari, ed. Tadao Ando Museums (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009).

6 For details on Sambuichi’s project see the special issue, "Sambuichi," JA: The Japan Architect 81 (2011). For drawings and descriptions of Ando’s work on Mount Rokkō, see Yukio Futagawa, ed. Tadao Ando Details (Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita, 1991); Jodidio, Ando: Complete Works; Richard Pare and Tom Heneghan, The Colours of Light: Tadao Ando Architecture (London: Phaidon, 2000).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top