-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

From Edo to 21st-Century Tokyo: A New 'Floating World'

Danielle S. Willkens is the 2015 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

May, sadly, marked the end of my time in Japan as well as the conclusion of my travels sponsored by the Society of Architectural Historians’ H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. To say that a year has flown by is an understatement and my final blog post will reflect upon the experiences and lessons garnered from this incredible experience. This penultimate post will address some of the sites that occupied my last few weeks in Japan, illustrated in this comprehensive Google Map, as well as my time in the nation’s capital.

Along with a newfound appreciation for ukiyo-e, I have found that my time in Japan has produced a new interpretation of the famous ‘pictures of the floating world’. I have been fortunate to witness some of the colorful festivals depicted in woodcuts that still populate the streets of Tokyo during certain times of the year (Video 1). The scenes of urbanity in ukiyo-e from the Edo period, featuring pleasure districts and elaborate theatre costumes, have new forms: in the birth nation of Nintendo, visitors can now rent costumes and go-karts, bringing Mario Kart to life in the busy streets of Tokyo’s Harajuku district. With these examples in mind, it will be interesting to see how Japan expands its definition of heritage and marks the Edo-Tokyo legacy when Tokyo takes the stage as the host for the 2019 Rugby World Cup and the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Video 1. Footage from several days of the Sanja Matsuri festival, held in Asakusa, Tokyo from May 19 to 21, 2017. Although the festival has religious components, the street picnics and open garages in the urban alleys reveal that the event unites a close-knit community. For one weekend, people of all ages come together for an electronic-free celebration of local heritage, craft, and family.

Sites in Conversation and at Odds

Thanks to several Japan Rail Passes, I was able to traverse a substantial portion of the nation, undertaking day trips that would be impossible without such a well-connected rail network. With such ease of travel, it was possible to put geographically and historically disparate sites in conversation. For example, the Daibutsu [Great Buddha] (1252) in the ancient capital of Kamakura, surrounded by a dry garden and situated in a coastal city thirty miles southwest of Tokyo, now has a modern counterpart in Hokkaido at the Hill of Buddha (2015), a landscape, enclosure, and entry sequence scheme designed by Tadao Ando (Figures 1-3). Pilgrims can actually occupy the interior of the cast form of the Kamakura Daibutsu, composed of thirty separate sections that were carefully connected through an innovative system of metal joinery, whereas visitors to the Hill of Buddha may share a partially enclosed concrete ‘sanctuary’ with the stone Daibutsu (Figures 4 and 5). Although both Daibutsu are about 44-feet tall and use the surrounding mountains as borrowed landscapes within the background, there is a distinctive use of miegakure [hide and reveal] at both sites: the ancient Daibutsu is only visible after passing though the gates and forest of the sacred complex, an area that would have offered welcome quietude within a city that served as the capital from 1192-1333.1 Although a much more expansive landscape situated within the Makomanai Takino Cemetery near Sapporo, Hokkaido, the Daibutsu at the Hill of Buddha is only fully visible from within the shallow concrete dome. From within the dome, it becomes clear that simple architectural elements play several roles, manipulating a visitor’s sense of scale and the perception of the site (Figures 6 and 7). For example, from afar the structure’s oculus serves the purpose of revealing the top of the Buddha’s head but from within the dome, this aperture becomes a framing element for the sky and thereby shifts the visitor’s attention from the corporeal to the ephemeral (Video 2).

Figures 1-3. Views of the Daibutsu in Kamakura and the Hill of Buddha.

Figures 4 and 5. Although open-air sites of worship, both sites have distinctive interior spaces.

Figures 6 and 7. Views of the Diabutsu from the Hill of Buddha, illustrating the use of compression and expansion within Ando’s constructed landscape and the complementing concrete structure.

Video 2. Aerial footage of the Hill of Buddha (2015), designed by Tadao Ando and situated within the Makomanai Takino Cemetery near Sapporo, Hokkaido. The project is just one compelling element within a landscape near a national forest. The cemetery has several, rolling hills that are dotted with vertical tombs and near the Hill of Buddha is a replica of Stonehenge and two rows of life-size copies of Moai from Easter Island.

Throughout my time in Japan, I found other unexpected parallels in the natural and built environment. Although one could read the piloti of the Museum of Modern Art (1951) in Kamakura by Junzo Sakakura (1901-1969) as an ode to Sakakura’s time working in the office of Le Crobusier, the form also has roots in the Japanese landscape traditions that can bee seen in Kanazawa’s expansive garden, Kenrokuen (c.1871). Here, manmade poles of bamboo and cypress provide additional support for the sprawling limbs of the Karasaki pine. Unlike cable ties, this system uses elements made directly from nature to support live trees and it is difficult not to see parallels between the semi-submerged supports at Kenrokuen’s ponds and the floating piloti of Sakakura’s Museum of Modern Art (Figure 8 and Video 3).

Figures 8. Views of the tree supports fort the Karasaki pine in Kanazawa’s Kenrokuen garden.

Video 3. Aerial footage of the Museum of Modern Art (1951) in Kamakura by Junzo Sakakura (1901-1969). As an employee at Le Corbusier’s office in Paris (1930-1937) and, later, a design partner on the National Museum of Western Art (1959) in Tokyo’s Ueno Park, Sakakura was a leader in the emergence of modernism. Many of his preserved projects, such as Kamakura’s Museum of Modern Art demonstrated his interpretation of the five points of architecture.

The commonalities in visual and structural systems in the built environment that can be found across time and place in sites throughout Japan’s varied geography also make the certain cultural and historical juxtapositions more apparent. For a portion of early May, I found myself at two extremes in Japan: (1) revisiting the northernmost island to complete a digital documentation project at the Hokkaido Historical Village and explore the region around Sapporo that had, largely, emerged from the thick blankets of winter’s snow and (2) and flying south to see the odd combination of resort life and postwar heritage tourism in Okinawa (Figure 9). Unlike Honshu, the densely populated urban area around the prefectural capital of Naha on Okinawa is entirely dependent on vehicular traffic since the only railway on the island is a limited monorail system. The architecture of the region can also be distinguished from mainland Japan since there is a different material palette, consisting mainly Ryukyu lime stone, porous coral, and concrete, and the buildings are designed for air flow to combat the warm, wet climate while using heavy roofing materials to protect against the constant threat of tropical storms. The adaptations in the built environment have roots in the history of the island: once part of the Kingdom of Ryukyu (1429-1879), Okinawa is actually comprised of the main island and 160 smaller ones, a quarter of which are uninhabited.

Figure 9. A view of Naha, Okinawa from Hacksaw Ridge.

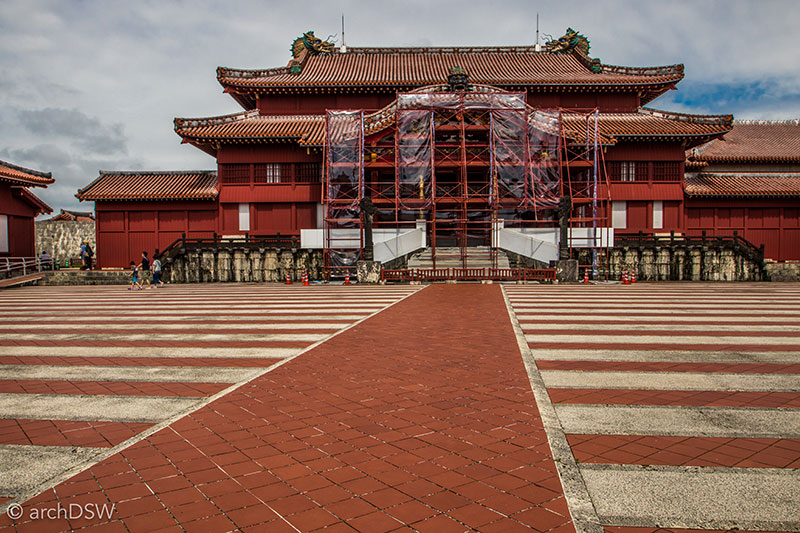

The proportions, detailing, use of materials, and color scheme of the Shuri Castle (begun 15th century; 1982-1992 reconstruction) clearly articulate how the architecture of the Ryukyu Kingdom responded to the tropical climate (Figures 10 and 11). The majority of Ryukyu’s fifteen defensive structures were destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa; therefore, the island’s initial tourism campaigns, begun after governmental control returned to the prefecture in 1972, were focused on war tourism. This eventually led to endeavors in natural tourism: bolstered by the success of the World’s ‘Marine’ Fair at the Ocean Expo Park in 1975, now the site of the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium (2002), the early 1980s featured a growing number of resorts as well as the import of pineapples, mangoes, and other non-native palms to support the island’s ambition to be ‘Japan’s Hawaii’.2 This resort culture, however, was developing in parallel with the growth of American military bases on the island and continued ‘dark tourism’ of beachheads, ridges, and caves that were intense battlegrounds during World War II. Although the only museum dedicated to the Battle of Okinawa has restricted access, housed within Camp Kinser, one of the island’s Marine Corps bases, several memorials and interpretative boards can be found around the capital as well as other coastal sites on the main island. Unlike Tokyo and other cities in Japan, the scars of World War II are still very palpable in Okinawa but, as an economic driver, they have been absorbed into the landscape of tourism.

Figures 10 and 11. With the exception of underground tunnels and a few defensive walls, Shuri Castle was entirely destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa. The Shureimon [Gate of Courtyesy] (1958) was the first structure reconstructed at the complex and a reconstruction of the Seiden gate was the main feature of the 1984 Sapporo Snow Festival. After much debate, the main buildings of Shuri Castle were reconstructed based on records from the 1715 iteration of the complex.

The Museumification of Edo-Tokyo

Home to nearly 38 million, Toyko-Yokohama is the largest city in the world and its population is 22% larger than second largest city of Jakarta. As a high-income city filled with large contemporary museums and an ever-changing skyline with a plethora of experimental structures and facades, it can be hard to find remnants of Edo within 21st century Tokyo. Although there are pockets within the city where one can wander preserved streets that are reminiscent of ukiyo-e, visits to two sites are essential for comprehending the architectural and urban evolution of the city from the 17th century to the present day: the Edo-Tokyo Museum (1993) by Metabolist architect Kiyonori Kitutake (1928-2011) in the Ryogoku district and its partner site, the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum (1993), located west of the city in Koganei Park.

From the observation platforms of Nikken Sekkei's Tokyo Skytree (2012), the Edo-Tokyo Museum looks like a cruise ship floating amid the city's blocks, making its way towards the Sumida River (Figures 12 and 13). Passing through the underside of the lofted building along a series of long escalators, the permanent exhibit galleries occupy the fifth floor and a gallery on the sixth floor, connected by a full-scale reproduction of the northern portion of the wooden Nihonbashi Bridge (b.1603, reconstructed 1806-1829). Within this massive, double height space, the colorful exhibits of festival floats and building reproductions, some at full scale, standout against the black background while other objects are suspended from the large network of space frames that the disappear into the dark ceiling. Without windows in the gallery, the museum creates another world where it is easy to lose track of the hours spent reading and studying the displays. Here, the cruise ship allusion on the exterior serves an extensive vessel for collections on the interior. Informative and, frankly, overwhelming, the museum’s interpretive boards, model descriptions, and interactive exhibits feature several languages and as a relatively uncommon strategy for many of Japan’s other museums, this indicates that the Edo-Tokyo Museum aspires to engage with a wide range of visitors from across the globe.3

Figures 12 and 13. Views of the Edo Tokyo Museum in Ryōgoku district of eastern Tokyo.

With reference to the gilded phoenixes featured atop the festival floats of Sanja Matsuri in the Asakusa district of Tokyo, a theme for Edo-Tokyo’s urban planning seems to have been renewal and growth born from destruction. In Edo, merchants could expect that their business would burn twice a decade. In addition to events like the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 that destroyed more than half the city, residents had to contend with disease outbreaks, an unkind climate, earthquakes, and tsunamis (Figure 15).4

Figure 14. The Ueno Fire Department Watch Tower (1925) in the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum. This structure originally sat atop a steel and wood tower standing nearly 80-feet tall.

Nonetheless, Edo was a city famous for its lively markets, high literacy rates, and entertainment districts. The most famous of these was Yoshiwara and although it originally developed on the outskirts of Edo during the early 17th century, the growth of the city and popularity of Yoshiwara’s attractions meant that this moated pleasure district eventually became an island of entertainment in the center of the city. From surviving descriptions and images, it appears that Yoshiwara operated around the clock. With its emphasis on beauty and an overabundance of both vice and visual stimulation, it is easy to envision the bustling commercialism of Shibuya or the gleaming facades of luxury stores found in Omotesandō or Ginza as 21st century reincarnations of Yoshiwara's indulgent aestheticism (Figure 15).

Figure 15. A collage of facades found in the prime shopping districts of Omotesandō and Ginza. Clockwise from top left: Dior Omotesandō (2004) by SANAA, Louis Vuitton Ginza (2014) by Aoki Jun & Associates, Mikimoto Ginza 2 (2005) by Toyo Ito & Associates, Stella McCartney flagship (2012) by Takenaka, and the building that arguably escalated the competition for architectural experimentation in Tokyo’s retail districts, the Prada Aoyoma (2003) by Herzog & de Meuron.

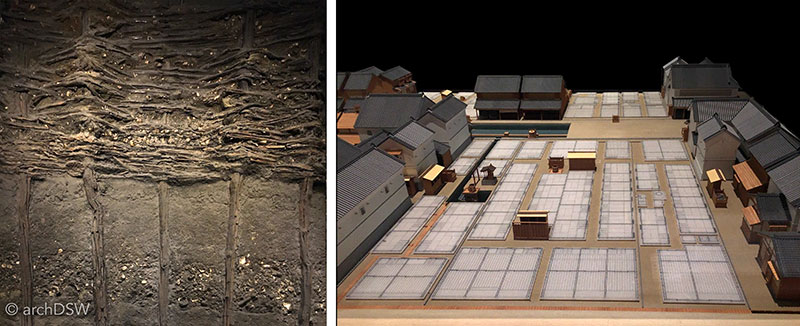

Although not explicitly named as a key focus of the museum, information about architecture and urban infrastructure can be found throughout the Edo-Tokyo Museum. Through the provided drawings and models, visitors can explore water systems, townhouse developments [ryōgawa-chō], and cultural sites of Edo (Figure 16). There is even a full-scale reproduction of the earthworks employed to expand Edo into the sea, using a layering system of wooden board, stone, straw, and sand to create submerged retaining walls (Figure 16). Like other museums in the nation, accurate plans with proper line weight and orthographic drawing conventions fill the museum’s boards and this method of disseminating the true language of architecture continues to be refreshing: these representations are not diluted into the more basic plan diagrams that typically appear at historic sites but, instead, encourage visitors to develop the ability to read and interpret architectural drawings.

Figure 16. A diptych showing the full-scale retaining wall reconstruction from Edo’s land expansion and a model of the layout of a merchant block.

As Tokyo began an ambitious redevelopment campaign after World War II, it became clear that rising property values and the charge for density would pose a threat to surviving historic structures.5 Eventually, individual efforts to dismantle, save, and relocate structures to open sites outside of the concentration of the city became a governmental initiative and when the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum opened in 1993, it was home to only twelve buildings. Now, thirty are under the care of the curators and the site describes itself as a place to “discover the Japanese nostalgic life”. Counting the Hokkaido Historical Village outside of Sapporo, the Hida Folk Village in Takayama, and Meiji-mura outside of Nagoya, the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum is the fourth architectural museum dedicated to relocated structures that I have been able to visit in Japan. Although the program of the museums is similar, the physical locations and collections certainly differ. Unlike Meiji-mura or Hida, the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum is situated on a fairly flat site. This, paired with its extensive canopy from a densely forested landscape, provided a very welcome atmosphere for explorations in the rising heat of May. There were, however, frequent announcements over the museum's loud speakers that reminded visitors, in Japanese, Chinese and English, to drink water and rest.

Unlike the residential structures at the other architectural museums, the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum situates homes within plots that have ‘street’ frontages and backyards; there is also a flowering and semi-wild landscape that is absent from some of the other museums. Unlike the purely picturesque arrangement of other open-air architectural museums, the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum provides a narrative. Here, one can transition from the western side of the park with vernacular structures, such as the residences and storehouses of farmers, to a suburban area and, eventually, an urbanized zone of mixed-use buildings on the eastern edge of the park (Figures 17-22). The urban and suburban areas of the museum showcase different approaches to Western architectural influences during the Meiji and Taisho eras, placing examples of Japanese modernism across from the sprawling homes that were inspired by monastic complexes and had both Japanese and 'Western-styled' rooms that were ordered through bifurcations in plan or section.

Figures 17 and 18. Kunio Maekawa (1905-1986) was one of three Japanese architects who apprenticed in Le Corbusier’s office in Paris. After two year abroad he returned to Japan and established his own practice. His most famous project is the concert and exhibition hall known as the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan (1961) that is located in Ueno Park, across from Corbusier’s National Museum of Western Art (1954-1959). The images shown here illustrated his home and office (1942), once in Shinagawa-ku. Maekawa’s home employs a symmetrical plan with an off-center entry to the living room that features a gallery above the northern side. Forming the core of the home, the living room is flanked by the bedroom, bath and kitchen on one side and the studio and a maid's room on the other. The steep gable roof, typically found in Japanese farmhouses, was reinterpreted with a glazed wall and throughout the home visitors can see how Maekawa adapted traditional Japanese joinery methods to connect wood, steel, and glass. As a fairly large and light-filled home, the project demonstrates the how modernism could thrive despite the rationing of building materials during World War II.

Figure 19. This photography studio (1937) was added to the museum in 1997 and became the 20th building in the park. With Werkbund and Art Deco elements, the concrete structure once occupied a corner site in Tokiwadai but it was moved due to a street-widening project. Like the other photography studios preserved at Meiji-mura and the Hokkaido Historical Village, this building employs a glazed northern wall and skylights. However, unlike the other studios that relied on fabric shading devices, the Tokiwadai studio had translucent windows.

Figure 20. This view shows the urbanized, eastern section of the museum, with a ferro-concrete storehouse in the foreground followed by two, narrow facades of a stationary store and the Hanaichi flower shop (1927). Most of the buildings in the eastern section of the open-air museum are examples of kanban [signboard architecture]. This style was popular during the building boom after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Moving away from facades of wood and paper with layered screens, kanban used copper sheets, glass, and signage to create patterns and advertisements.

Figure 21. An image of the ordered interior of the "Takei sanshodo" Stationary Store (1927). A characteristic of kanban was that unlike traditional Japanese structures, the interior arrangement and exterior cladding were disconnected.

Figure 22. As an uncommon example of a corner kanban, the Martin Shoten Kitchenware Store (1926) was originally in Kanda Jimbo-cho and features a façade of woven copper sheets.

Figure 23. The House of Uemura Saburo (1927) was originally located in Shintomi and the scars on the copper sheet façade reveal damage from World War II bombings. The differences between the front façade and alley sides of the building show how the building’s form and decoration evolved over time, resulting in something of a Frankenstein structure.

Figures 24 and 25. With oversized karahafu (bow-shaped gables), the structure and exterior decoration of the Kodakara-yu public baths (1929) from Senju motomachi allude to the architecture of shrines and temples. The top-lit interior, however, has modern lighting and playful tile paintings.

Tokyo 2020

The Edo-Tokyo Museums, like many others in the nation, are preparing to receive expanded visitor numbers in the coming years: the Edo-Tokyo Museum will close for substantial renovations from fall 2017 to spring 2018 and the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum plans to expand its visitor numbers by recruiting additional volunteers and installing new signage. These initiatives are in coordination with the upcoming Tokyo 2020 Olympics. The return of the summer Olympics to Japan is an important one for the nation, especially with respect to tourism and architectural initiatives. The Tokyo Olympics of 1964 marked the nation’s reintroduction to open borders, for foreigners and residents, and the games left a significant built legacy that showcased Japanese architectural invention.6 The 1964 games were the first held in Asia and the stadiums of Kenzo Tange (1913-2005) were muses for one of Japan’s most prolific contemporary architects: Kengo Kuma (b.1954) (Figures 26-29). As noted in an interview by Brian Libby of Architect and in conversations with Balazs Bognar, AIA, the Design Director at Kengo Kuma and Associates who kindly toured a group of Auburn faculty and students through the firm’s model-filled studios in late February, Kuma san described his visit to Tange’s Olympic venues at age ten as, “a turning point in my life”.7 In those light-filled spaces, he was inspired to become an architect because of Tange's combination of Japanese form and materials with new technology.

Figures 26 and 27. Kenzo Tange’s Yoyogi National Stadium (1964) was built as the venue for swimming and diving events at the 1964 Olympics. The larger of the two structures in Tange’s Olympic park, both composed of concrete and a steel cable tension system for the roof, will be used in the 2020 games as the handball venue.

Figures 28 and 29. Kenzo Tange’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium (1964) was the basketball venue in the 1964 games but since it seats only 3,400 it will not be used during the 2020 games.

After debates over budgets and the concerns of commissioning a foreign architect for such an important national project, Zaha Hadid’s competition-winning design for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Stadium was replaced with one by Kuma and the project broke ground in late 2016. Based on the construction underway, press releases, and the content of 2016 Closing Ceremonies, previewing Tokyo as the next host city for the Summer Olympics, the 2020 games may be filled with technology and themes of sustainability and recovery. In the spirit of mono no aware [awareness of the precarious nature of things and sense of wistfulness for their passing], the 2020 games may be an opportunity to attract new visitors to Japan and showcase redevelopment in areas impacted by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. The former is of particular concern since Japan’s population is currently declining and estimates warn that the nation’s population of 127 million could shrink by 42 million in the next fifty years.8 At the present moment, more than 10% of the nation’s population is over the age of 75. Despite the possible implications of such a dramatic population shift in Japan, the physical environment of the capital shows no signs of development decline and preparations for the games are already reshaping Tokyo. However, it will be interesting to see how future tourism campaigns can influence a new generation of architects by showcasing Tokyo’s compelling combination of 20th-century buildings by foreign architects, Metabolist and futurist experiments, and soaring towers (Figures 30-34).

Figure 30. An enlarged entry plaza and circulation scheme is rapidly progressing at Tokyo Station (1914; 1956; 1991; 2012).

Figure 31. A view of Le Corbusier’s National Museum of Western Art (1959) in Tokyo’s Ueno Park.

Figure 32. The deteriorated state of the Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972) by Kisho Kurokawa.

Figure 33. A view of the parasitic Aoyoma Technical College (1990) by Makoto Sei Watanabe.

Figure 34. A vertigo-inducing view of the towers of Tokyo Midtown (2007), a mixed-used master planning project by SOM with paired cultural assets in the form of the Suntory Museum of Art (2007) Kengo Kuma & Associates and the 21_21 Design Site by Tadao Ando (2007; 2017)

A Traveler’s Notes

In a few weeks, I will compose my final blog entry for my tenure as the recipient of the 2015 SAH Brooks Travelling Fellowship, reflecting on my time as a fellow and how I can already see the year of sponsored research informing future paths of inquiry. Thankfully, I will have the opportunity to share some of this work at the upcoming SAH Annual Conference in Glasgow, where I will be presenting a paper on ‘Iceland’s Basalt Architecture and the Tourist Conundrum’ in the panel on Carbon and Architecture and co-moderating the SAHGB’s Roundtable on ‘The Audience for Architectural History in the 21st Century’.

Since a primary focus of my experiential research sponsored by the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship is cultural heritage tourism, it seemed apropos to conclude this post, and my time in Japan, with a few practical notes and suggestions for any readers who hope to visit the island in the near future:

- As mentioned in the ‘Railroads and Reconstructions’ blog post, get a Japan Rail Pass. If you are making a round trip between Tokyo and Kyoto, the 7-day pass will pay for itself; but the real benefit of the pass is the flexibility to jump on and off Japan Rail (JR) trains as well as bullet trains (except the Mizomi and Nizomi). Paired with the Google Maps app and HyperDia, it is possible to navigate the maze of Japan's impeccable rail system. The rail passes are available to foreigners on a tourist visa and passes are good for seven, fourteen, or twenty-one consecutive days. Until March 2017, the passes could only be purchased through a vendor in a tourist's home country. However, on a trial basis, the passes will be sold in select train stations in Japan until spring 2018. Although this option is very useful for changing travel plans, and I admittedly purchased two weekly passes on-site, they are a bit more expensive than those acquired in your country of residence.

- Research the dates and locations of heritage festivals: seeing floats and shrines in communal procession is entirely different than observing these intricately carved and richly painted objects in static form, mounted behind fine metal fencing or glass.

- Visits to most Imperial sites, especially those in Tokyo and Kyoto, require arrangement months in advance. Most of the sites now use an online reservation system and they are booked well in advance. Also, be prepared that many of these sites prohibit not only photography but also sketching.

- Bring your hiking shoes. Nearly 75% of the nation is mountainous and there are several sites, such as the ‘Mountain Temple’ of Yama-dera, that require a fairly strenuous climb but reward intrepid visitors with incredible views and sacred sites with elaborate architectural detailing.

- Similar to my explorations beyond Reykjavík, Iceland, and Havana, Cuba, a trip to see Japan's architectural heritage should certainly include time outside of the capital city. Tokyo is dense, crowded, and, largely, a city of later 20th- and early 21st-century buildings. The capital has a wealth of interesting sites but its urban composition needs to be put in conversation with the two other large cities of the nation: Kyoto and Osaka. This urban triad houses 70% of the nation's population so trips to other cities and towns are essential to experiencing Japanese urbanity at different scales. Kamakura, Himeji, and Takayama have incredibly preserved heritage sites from the Edo era and earlier. Perhaps the most surprising destination during my travels in Japan was the northern island of Hokkaido (Video 4). It is often absent from discussions on Japanese architecture, however Hokkaido offers unparalleled opportunities to explore Japan’s industrial colonization of the island during the Meiji Era. Once home to the Ainu and resilient fishermen who braved incredible conditions, Hokkaido became a home to industrial production such as breweries, productive port cities like Hakodate, and, in the northern city of Abashiri, a barren and isolated site to send convicts to a dim fate within a panopticon-Inspire structure. Although an island primarily advertised to tourists as a site for exploring national parks, lakes, and a largely untouched coastline, the built heritage of Hokkaido should not be overlooked. The majority of Hokkaido’s architectural sites have interpretation in English and although portions of Hokkaido were bombed during the end of World War II, many historic structures escaped destruction. As a less densely populated island, these structures also evaded demolition due to development in the later 20th century. In addition to a wealth of Meiji Era architectural, ranging from civic buildings to residences and commercial structures, Hokkaido has intriguing contemporary residences, public parks with art installations such as sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s Moerenuma Parl (1988-2005), and iconic religious structures by Tadao Ando, such as the Church on the Water (1985) and the Hill of Buddha (2015).

Video 4. Aerial footage of the bay of Hakodate on Hokkaido from the western side of Mount Hakodate, featuring the foreigner’s cemetery and the Quarantine Office (1896). Many of the Meiji-era buildings, such as the Prefectural Office Hokodate Branch (1909), Old Public Hall (1910), the Iai Kindergarten (1913), the Russian Orthodox Church (1916), and various consulate offices are not visible in the footage since they are nestled into the northern edge of Mount Hakodate but the view provides an interesting perspective of the port’s geography that Commodore Perry surveyed in May 1854.

Bibliography

Figal, Gerald. "Between War and Tropics: Heritage Tourism in Postwar Okinawa." The Public Historian 30, no. 2 (2008): 83-107.

Marks, Andreas. Japan Journeys. Tokyo: Tuttle, 2015.

Miller, David March. The Official History of the Olympic Games and the Ioc: Athens to London 1894-2012. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2012.

Ohno, Hidetoshi. "Tokyo 2050 Fivercity." In A Japanese Anthology: Cutting Edge Architecture, edited by Leone Spita, 138-45. Rome: Gangemi Editore, 2015.

2 Gerald Figal, "Between War and Tropics: Heritage Tourism in Postwar Okinawa," The Public Historian 30, no. 2 (2008): 95.

3 Boards are in Japanese and English while loose sheets are provided in French, Chinese, and Spanish.

4 The Great Earthquake of Ansei in 1855 and Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 had the greatest impacts on the city.

5 While certainly not the revisionist history presented at the Yūshūkan War Memorial Museum, the Edo-Tokyo Museum does not address Japan’s aggressive military campaigns across Asia in the 1930s nor does it mention the attack on Pearl Harbor, simply noting that the, "outbreak of the Pacific War [was] in December 1941." Air raids from February to May 1945 destroyed more than 50% of Tokyo’s urban fabric and the city of 7 million shrank to 2.4 million due to relocation and war casualties.

6 For specific notes on the 1964 games see David March Miller, The Official History of the Olympic Games and the Ioc: Athens to London 1894-2012 (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2012).

7 For a transcription of the 2016 Architect interview see http://www.architectmagazine.com/design/q-a-kengo-kuma-on-his-design-approach_o

8 See Hidetoshi Ohno, "Tokyo 2050 Fivercity," in A Japanese Anthology: Cutting Edge Architecture, ed. Leone Spita (Rome: Gangemi Editore, 2015).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top