-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Winchester’s William Walker

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

For this month’s post, I had originally planned to write on decorated vault ceilings in the UK, but only in an instance, and indeed at the very last minute, was I compelled to change my mind and write instead about a man whose stirring story has captivated me since I encountered it in Winchester. I ask in advance for your pardon and indulgence as the content herewith may deviate in some ways from my original scope which is ornamentation. Having no knowledge of the man called the cathedral diver before now, I am awestruck and deeply inspired by the underlining message of his story. The story is one that speaks to dedication driven by a sense of value and purpose—something I have continued to see in different forms all through my fellowship travels. I can only hope that I, being a budding historian, will find purpose for myself and my life (considering where I am from) in the telling and retelling of critical stories that will redirect our thoughts to that which is past but must never be forgotten.

In the easy-going town of Winchester, there is no dearth or want for the telling of Walker’s story. For to all who care to listen, a true Winchester native will eagerly tell you that the glorious cathedral you see today stands only because a man of compulsive dedication to purpose gave his time, his skill, and his strength to seeing that the building remains upright. With such pride and love they speak of him as the deep water worker—him, being no other than Winchester’s William Walker.

Figure 1: Western façade of the Winchester Cathedral.

Figure 2: A view of the Winchester Cathedral from the northern side.

Figure 3: The beautiful streets of Winchester, not far from the cathedral.

Figure 4: The portrait photography of William Walker. Photo by John Crook. Source.

As far as Winchester is concerned, the diver’s helmet has become an icon for heroism and preservation. One such helmet caught my attention as I made my way to the cathedral. Having passed the statue of King Alfred the Great on to the Broadway, past the Guildhall Winchester, then onto High Street going towards the Winchester Museum, just along the Market Street, one will notice a diver’s helmet adorning a signpost that reads “William Walker”. I thought nothing of it initially but took a photo anyhow as it reminded me of one of my all-time favourite movies by Cuba Gooding Jr. and Robert De Niro: Men of Honour, a true-life story of the first black US Navy deep-sea diver Carl Brashear. Shortly after I photographed the helmet, I returned to my full medieval architecture mode. And there it was, yet another beauty of a building: The Winchester Cathedral. Like all the others I have seen, it is majestic and visually imposing. It speaks for the centuries gone by and does little to hide its Norman roots. Now inside the nave and barely into my tour, in a dark corner of the cathedral, again was I confronted by a diver’s helmet very much like the one I had seen a few streets away. At this instance, I knew there must be something about this place and diving. My wonder didn’t last a second, for right beside the helmet in the cathedral one will see a small bronze statue of a man famed to have saved the cathedral from collapse with his own hands in the very early years of the 20th century. Needless to say that from here on I went deep into the matter.

Figure 5: The diver’s helmet and signpost off Market Street in Winchester.

Figure 6: The Statue of Kind Alfred the Great at the Broadway roundabout. Sculpted by Hamo Thornycroft. The plaque attached to the base of the sculpture it reads: “To the founder of the Kingdom and Nation. D. October DCCCCI.”

Figure 7: The Guildhall Winchester on Broadway Street Winchester.

Figure 8: A Siebe Gorman & Company Diver’s Helmet worn by the cathedral diver on display inside the nave of the Winchester Cathedral.

Figure 9: A bronze statue of William Walker displayed beside the Siebe Gorman Helmet and in honour of Walker’s work inside the Winchester Cathedral.

Figure 10: Ornamented cross outside the Winchester Cathedral on the western front.

Figure 11: On display outside the cathedral: an artist impression of the Old Minster, one of the earlier structures on the same location before the present building.

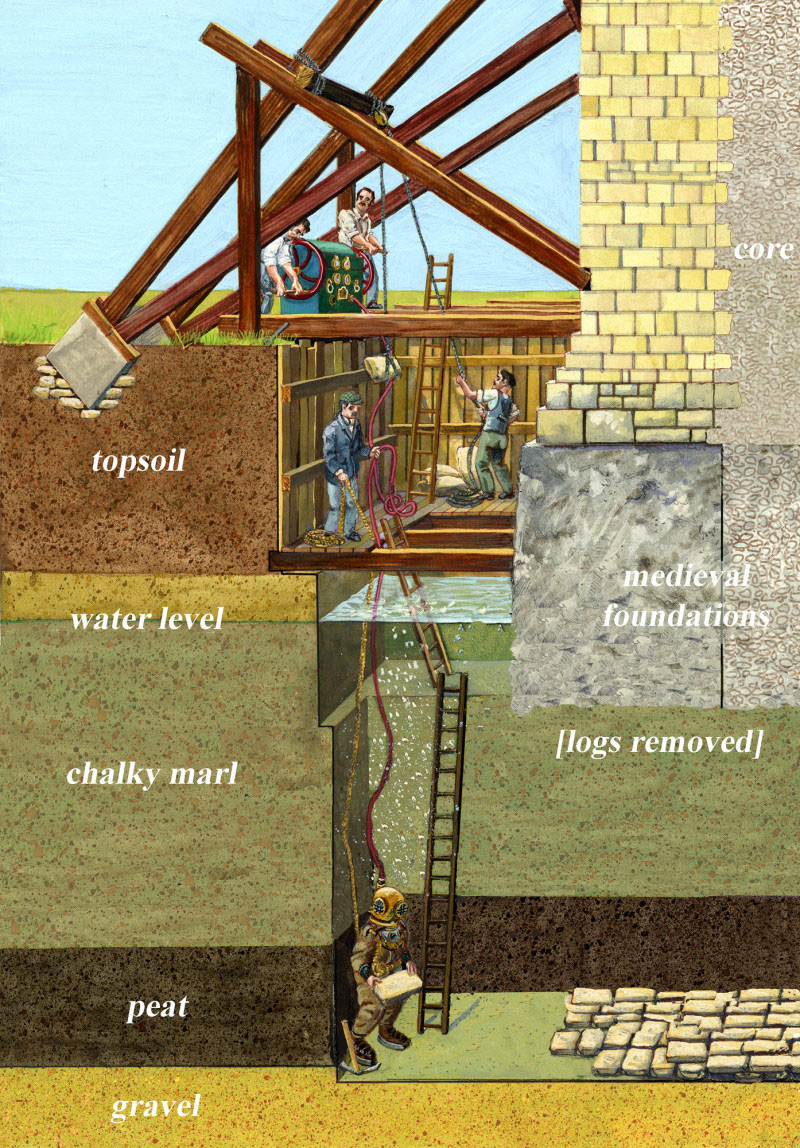

The story has it that Winchester Cathedral delicately stands on peaty soil with a high water table underneath it. In the early 1900s, huge cracks began to appear in the massive walls of the cathedral and chunks of stone occasionally fell to the ground. It was only a matter of time before it became clear that the building was in danger of imminent collapse. The architect Thomas Jackson was called upon to remedy the situation once and for all as the condition was getting dire by the day. After much consultation, Jackson decided to dig narrow trenches underneath the walls of the building and fill them with concrete. These would need to reach 4 meters (13 feet) below the water table to be effective.1 The plan to dig pits through which the foundations of the cathedral wall would be shored up almost failed before it even started—water flooded the trenches so rapidly as the workmen dug that even a steam pump brought to the site could give no respite.

When the cathedral collapse almost seemed inevitable and as gloom covered the rescue project, a ray of hope came when the project’s engineer, Francis Fox, had a brilliant idea to call in a deep-sea diver to help out if the water couldn’t be held back.2 This was how the destiny of the cathedral and that of William Walker crossed paths and was sealed forever. Walker was an experienced diver working at Portsmouth dockyard and a native of Newington, Surrey.3

From 1906, using his bare hands to feel his way through the blackish muddy waters, William Walker laboured below the cathedral in total darkness for six hours every day at depths up to 6 meters (20 ft) for about six years, shoring up the foundation with bags of concrete prepared by the other workers. At the end of his work on the cathedral, Walker had packed the foundations with an estimated 25,000 bags of concrete, 115,000 concrete blocks, and 900,000 bricks.4 Not two, not five, but twenty-five thousand bags of concrete—by any account, this is an unprecedented scale of construction work done by a single man. Only after this could the waters be pumped out and huge buttresses added to the south side of the cathedral, and the building was safe at last.

Fig 12: William Walker is seen here being dressed by an aid. His total gear weighs an excess of 90 kgs and he will shortly after this photo make a 13 ft descent to the decaying Cathedral foundations. Photo by John Crook. Source.

Fig 13: Diagram showing the details of how William Walker worked in the almost six years at the depths beneath the cathedral walls. Source.

Fig 14: Massive bulwark is erected to support the cathedral structure as efforts continue to save the cathedral. Source.

So I stopped for a while to understand it. Six hours every day for six years. Burdened by the weight of the very gear that must keep you alive. And as if that weight of about 90 kg5 isn’t doing a good enough job of making your descent (and probably worse—your climb back up) into the abyss of Jackson’s murky water pits miserable and eventually painful, you are required still to carry a bag of concrete about 20 kg each time you go under, making Walker a catastrophic weight of about 110 kg on a ladder in the most precarious situation. Working in the deep dark abyss with only your imagination and whatever sensory feeling that is left on your fingertips in the cold waters for a sense of direction. I imagine he may occasionally find himself wresting his feet from the soft peat soil beneath him in order to make it back to the ladder where he may sometimes miss his steps on account of the weight of the gear. I see in William Walker a one-of-a-kind disposition to heritage and shared value. The cathedral must mean something to him or he must have a good understanding of what it meant to the people of Winchester—one or the other must be true but what is more, I presume, is his exceptional devotion to routine in a manner that gets tedious jobs done however the attending horror of monotony and repetition.

After finding the reason for the diver’s helmet iconography in Winchester town and to a reasonable extent knowing the contribution of William Walker to Winchester Cathedral, I was fatigued with awe and perplexed on every side for I could not wrap my mind around such devotion to a singular goal. It is almost like worship—how can an ordinary man be so inclined to a purpose for which little comfort is returned to him as a favour or payment? Do permit me to wager a thought. If there is anything clear to me on this matter, it is that far from ordinary is this man of Winchester and truly, the depths are where we may need to search to find any other in this age that will present the slightest dedication to a course as he did. I am gravely inspired by this act, particularly as I stand in front of the cathedral today. It is a beautiful thing to encounter the work of a beautiful mind. The outcome is honest, inspiring, and usually long lasting.

I cannot help but think about another place I know where a wonderful architectural heritage like this at the brink of collapse will warrant nothing near the trouble the Winchester folks have put in to save theirs, rather it will only elicit the following comment—oh well, it has served us well, over 400 years, the building is old and tired—what did you expect? Pull it down at once so it will not hurt anyone. We will build another one in a more modern style when we eventually get around to it. After all, the world is changing and follow the change, we must. I will here mention no names.

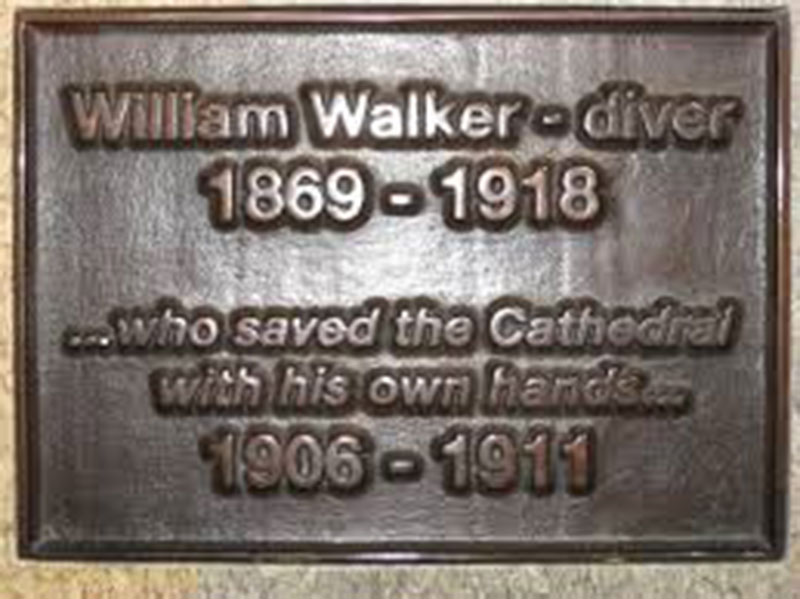

Walker is today remembered not for his thirty-seven years before his work at the cathedral, or the seven years he lived after the work before succumbing to influenza in the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. He is remembered singularly for his masterpiece contribution to the Winchester Cathedral.

I therefore contemplated on this and asked myself: when I am done here and returned to the dusts, when all is said and done in my life’s journey, will a bronze statue be made in my honour? This I very strongly doubt and am frankly not too concerned about. But, beyond the vanity of a cuprous cast, I am so deeply interested in what will be my aftermath. On account of the beautiful man I have found in Walker, I am thus forced to ponder quite intensely the thought or rather the question—what will I be remembered for when I am done and dusted? What tangible legacy will I bestow and honour my name with? The answer to this I currently do not have but hope to craft one as the days and years go by.

Fig 15: A plaque attached to the bronze statue of William Walker inside the Winchester Cathedral.

Winchester Cathedral Aside Walker and the Abbey at Bath

It is really tough to think of Winchester Cathedral aside Walker, but there are in fact other personalities, features, and events around this cathedral that are also very well significant. I will highlight a few here in photos.

Fig 16: A mortuary chest containing the bones of one of the Saxon kings resting on top of the presbytery screens.

Fig 17: A sculptural piece in the crypt of the Winchester Cathedral. Sound II by Antony Gormley was a gift from the famous artist. The cast was made from the artist’s own body.

Fig 18: A view of part of the choir of Winchester Cathedral facing the western end. Notice the impressive ornamental wooden screen.

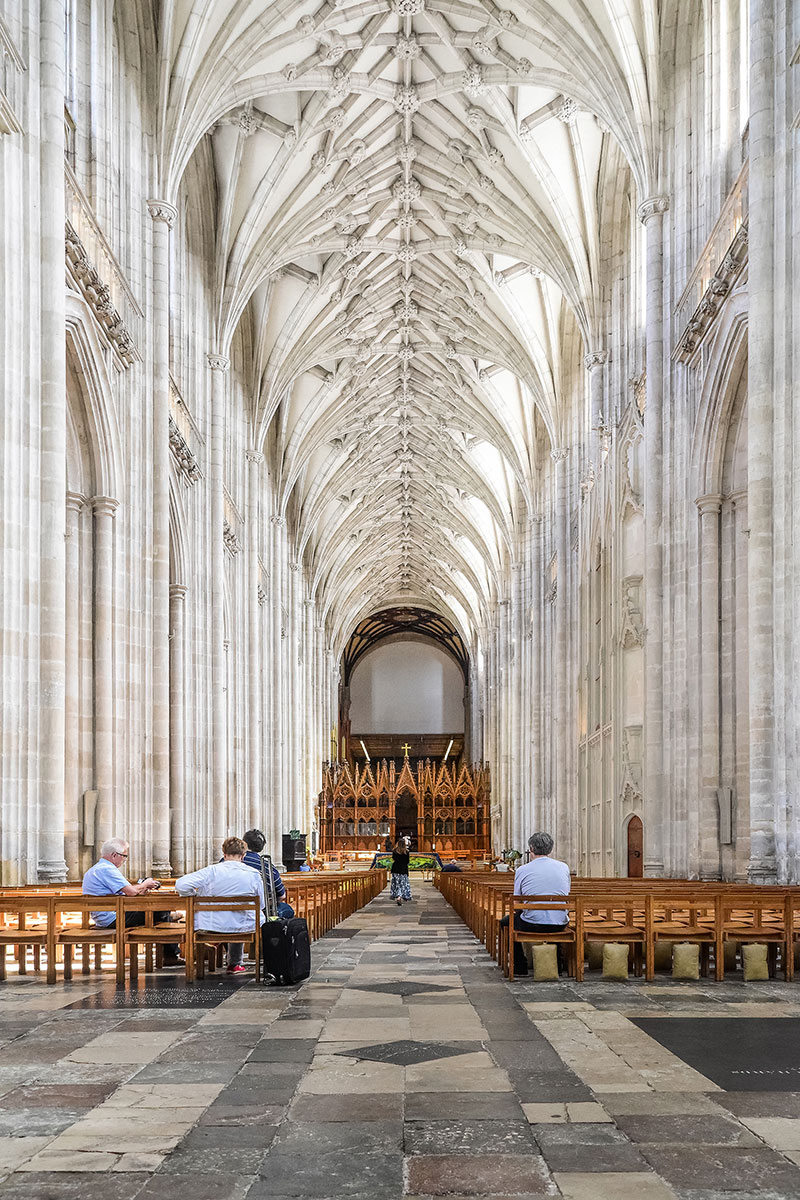

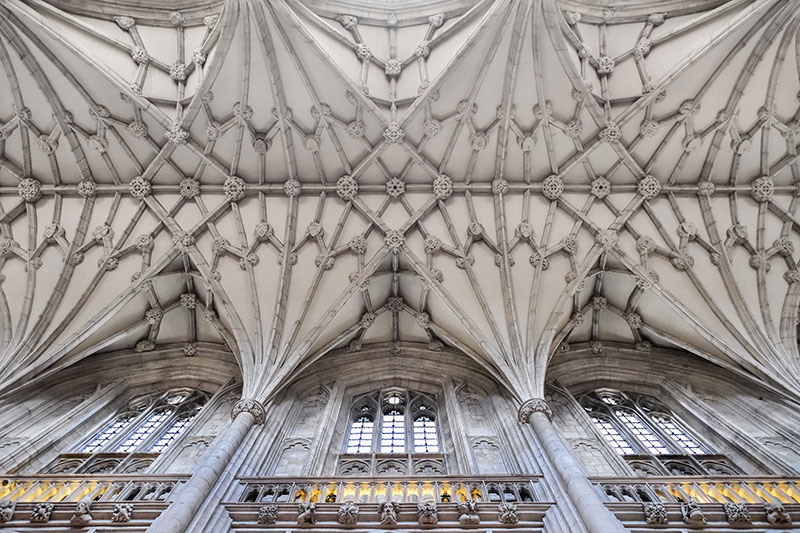

Fig 19: A view of the nave of the Winchester Cathedral.

Fig 20: Fan vault ceiling in the nave of the Winchester Cathedral.

Fig 21: The double red doors are the main entrance doors at the western end of the Winchester Cathedral.

I had visited Bath before coming to Winchester and Bath is a beautiful place. The Abbey at Bath was founded in the 8th century AD as a Benedictine monastery. The later Norman cathedral was built by John the Bishop of Bath in 1090. The present Bath Abbey however was built in 1499 replacing the ruins of the old cathedral and making it the last great Gothic church built in England.

Bath Abbey has a unique feature on its western front. One will see the unmistakable ladder incorporated into the towers of the church. The ladder features angels ascending and descending between the heavens and the earth visually capturing the dream of Bishop Oliver King and symbolically reaffirming the role of the church in our journey from the worldly earth to the heavens. Some accounts have it that the story claiming Bishop Oliver King saw the west front in a dream is a myth that was conjured up by Sir John Harington when he sought to raise funds for the Abbey roof a century after Bishop King’s death. Linking the fundraising to a spiritual encounter by their beloved former Bishop may convince the people to give more generously. Indeed one is inclined to believe that the Bishop Oliver King story is in fact a ruse as the representation on the cathedral is reminiscent of Jacob’s vision in the Bible, and it seems more plausible that the biblical Jacob story is the inspiration for the west front sculptural work. One other notable fixture of the western front is the solid oak door dated to the century after the Abbey was built. It was a gift to the Abbey from Sir Henry Montagu in memory of his brother Bishop James Montagu, the 17th-century Bishop of Baths and Wells. On the door we see three well-crafted shields representing the Montagu arms. Bath Abbey presents some of the most impressive fan vault designs I have seen in all of England and the parish does take pride in it. I was ever so kindly led to a spot where a mirror was strategically placed in the quire to help us appreciate the intricacy of the vault design without straining our necks by looking up. The clever mirror contraption gave an impressive and detailed reverse view of the vaults.

Outside Bath Abbey one will find nothing but tranquillity and beauty all around, in spite of the tourists. The town is packed with visitors and this may not be unconnected to the large number of historical sites to see in Bath. The Abbey’s brochure states that Bath Abbey is Britain’s most visited parish outside London—I saw enough people and beauty in the town to believe that wholly. I spent a few days inside the University of Bath campus taking photos and reading up on the venues I have visited.

Fig 22: A view of the Bath Abbey’s western front. To the right is a medieval roman public bath.

Fig 23: A view of the Bath Abbey from the eastern end of the building.

Fig 24: The ladders to Heaven—angels seen ascending and descending the ladder between Heaven and Earth. This is said to be a symbolic representation of the Bishop Oliver King’s vision of the western front that he saw in a dream. However, this was a ruse created by Sir John Harington to raise funds for Bath Abbey’s roof a century after the Bishop’s death.

Fig 25: An interesting symbol and signature of the Bishop Oliver King is seen on the northern and southern edge of the western front: an olive oil tree ringed by a king’s crown beneath a bishop’s mitre.

Fig 26: The nave of Bath Abbey.

Fig 27: The baptismal font of Bath Abbey, a Victorian style font with its counter-balance lid at the western end of the Abbey.

Fig 28: Ornate detail of the pews in the presbytery of Bath Abbey.

Fig 29: Oak wood ornamented pews in the presbytery of Bath Abbey

Fig 30: The tomb of Bishop James Montagu (1568–1618) with iron railing on the right of the north aisle. His family crests are very prominently displayed and can also be seen on Bath Abbey’s western doors, donated by his brother Sir Henry Montagu after the Bishop’s death.

Fig 31: A recumbent effigy of the Bishop James Montagu (1568–1618), Bishop of Bath and Wells, seen between the northern aisle and the nave.

Fig 32: Several burial memorials of famous people on the floor of the northern aisle inside Bath Abbey.

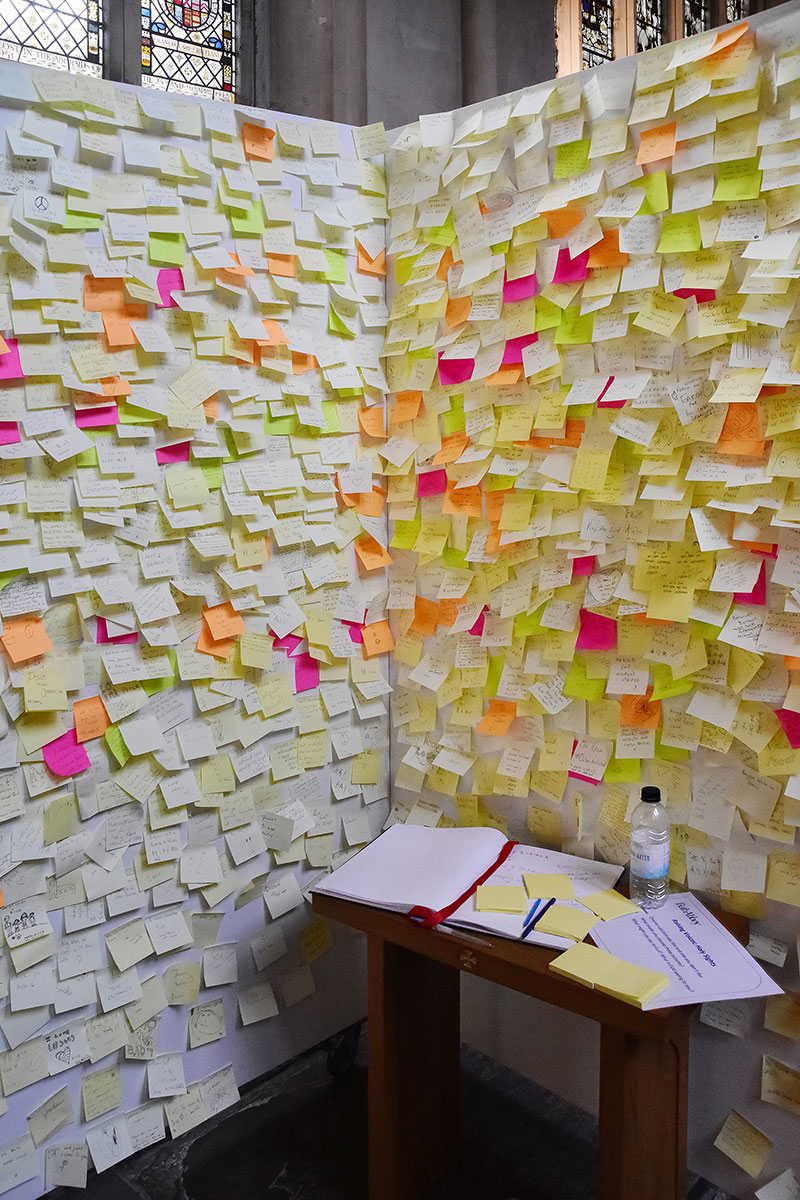

Fig 33: A graffiti prayer board for family members or for the world. Bath Abbey made post-it stickers available for visitors to leave a prayer note for friends, family and the world. People from around the world have prayer notes on the display board in different languages.

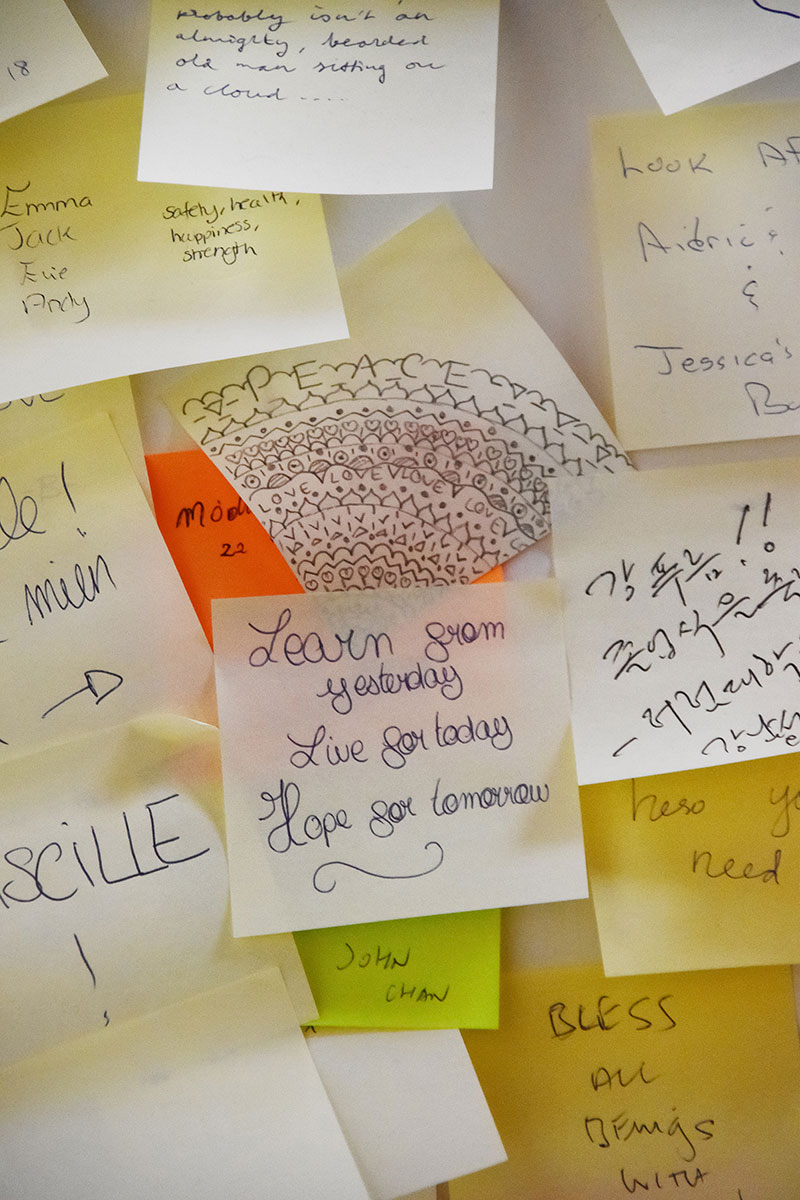

Fig 34: “Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow.” A close up of some of some of the notes.

Fig 35: Solid oak door at the western front of Bath Abbey, donated by Sir Henry Montagu in memory of his brother Bishop James Montagu, Bishop of Bath and Wells from 1608 –1618. Notice the three shields on the door, which are versions of the Montagu arms.

Fig 36: The town of Bath canal near Bath Abbey.

Fig 37: A colourful umbrella installation in Bath near the central station.

Fig 38: The University of Bath.

Fig 39: A beautiful lake with ducks inside the University of Bath

Fig 40: Nature inside the University of Bath.

I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the Dean and Chapter of Winchester Cathedral for

their kind permission to use photos from the Cathedral archive. Also, my gratitude to David Rymill, Archivist, Hampshire Archives and Local Studies, and Winchester Cathedral archivist for his kind assistance.

Reference:

1 Frederick Bussby, William Walker: The Diver Who Saved Winchester Cathedral, (Winchester: Friends of Winchester Cathedral UK., 1970)

2 “Winchester Cathedral,” accessed September 20, 2017, William Walker: The diver who saved the Cathedral http://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/our-heritage/famous-people/william-walker-the-diver-who-saved-the-cathedral/

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top