-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Crowds and the Architectural Monuments of Italy

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

All through my fellowship travels, one major challenge persists, one that I have done fairly well to conceal in my photographs—crowds. Nowhere more in Europe than in Italy did I experience the sheer weight of tourism as manifested in numbers. The popular sites were flooded with people and long queues, and while some of the venues were free to get in, I paid very dearly with 3–4 hours on the line in 3°C and gusty winds that made it all the more unbearable. For those from the temperate regions, I am sure this is nothing, but I am from the tropics and in Lagos we say, "My goodness it is so cold today," at 25°C.

Certainly I did not expect to be the only one to show up at a renowned public monument, yet, one is never prepared for the number of people one finds at such locations. The streets were overflowing with people from different nations. In some locations, it became significantly apparent so much so that it developed into a topic of discussion amongst the tourists themselves—if you have ever visited the Trevi Fountain in Rome, you will get a good sense of what I am saying.

Fig. 1: A mammoth crowd awaits you as you enter the Vatican square. The crowd has no respect for time or weather, it has become part of the constant ‘tapestry’ of the square.

Fig. 2: There is first the crowd and then there is the queue. Vendors will approach you to ask if you have a ticket to get into the Basilica as the queue is for those who are without one.

Fig. 3: A large number of people at the Trevi Fountain. Everyone is trying to get a photo of the beautiful work and everyone is getting in each other’s way.

Fig. 4: Another view of the crowd at the Trevi Fountain in Rome. Whichever way you turn, surely a crowd was there to bless or frustrate your view.

Fig. 5: A long queue which goes around two sides of the Cathedral del Fiore in Florence. It was very cold and the line moved only slowly. This was around 11 am. By the time I passed the cathedral around 7:30 pm, there were still people on a line waiting to go in.

Fig. 6: A huge crowd at the Piazza Navona, Rome. Notice the Egyptian styled obelisk in the middle of the fountain. A similar obelisk is found at the Piazza de la Rotunda in front of the Pantheon.

Fig. 7: The crowd in the nave of St Peter’s Basilica—truly not unexpected and actually flattering to the enigmatic building. It welcomes people from all over the world. In my 60 minutes or so inside this overwhelmingly beautiful space, I counted nine different languages from people who walked by until the words started sounding the same to me.

Fig. 8: Inside the Vatican Museum, one finds himself unconsciously forced to move with the pace and group agitation of the crowd with barely any time to contemplate what you are seeing.

No matter how well you plan your trip and itinerary, it is almost inescapable—you will come in contact with a sea of people in Italy, wherever you go; like you, they have also planned and travelled to see these monuments, probably with the hope of meeting as few people as possible at the entry points. The crowd in itself is not a bad thing. It speaks to the popularity of these sites and our unending connections to monuments, particularly those of a historic and religious nature. Also, with the crowd, comes the boom for a good percentage of local businesses. The funds collected at some of these sites may also serve as resource for the preservation and maintenance of the structure. There is, however, the challenge of the crowd ‘footprint’ and the consequent degrading of the priceless monuments. Some have argued—and I quite agree—that the idea of tourism funds helping the preservation of heritage sites is mostly a double edge sword as tourism itself contributes to the rapid degeneration of the sites.

Fig. 9: The Pantheon. The Piazza de la Rotunda in front has become a major hub for entertainment drawing tourists and large crowds to the square and the temple. Notice the people at the base of the photo.

Fig. 10: Inside the Rotunda.

Fig. 11: A view of part of the Colosseum with scores of visitors moving around.

Fig. 12: Groups of visitors at the western end of the Cathedral del Fiore, Florence.

Fig. 13: A view of the side of the Cathedral del Fiore with a long queue of people waiting to go in. The main entrance is on the western end.

Fig. 14: Me, getting impaled by a Roman centurion (costumed street actor) at the Piazza Navona. Local small businesses and initiatives thrive with the presence of tourists.

I am certain many would agree with me that when one thinks of contemplation, one often imagines serenity, little or no distractions, plenty of time to focus on a particular subject or idea with the aim of receiving something new from your rigorous but calm meditation on the subject in question. The idea of contemplation as described above is practically almost impossible at any architectural monument in Italy—at least the ones I visited. Why? The crowds and the energy at the sites are intensely positive but completely antithesis to the concept of quiet contemplation as articulated above. I probably felt the frustration most at the Vatican. The last time I saw that large of a crowd gathered in one place was at a festival I happened upon in my university days. The energy was high; everyone jostled for the right position to take a photograph of a sculptural piece or part of a building. There was hardly any time to properly observe and study the brilliant art pieces one is confronted with, as we moved from gallery to gallery. The crowd was constantly in the way and there is an unconscious pressure on the inside of you to keep moving as the crowd moves.

Jane Fawcett has discussed the dangers and impact of crowds on heritage sites.1 She herself remained conflicted on the issue of tourism and material heritage as it only makes sense that these structures, which hold a critical part of human history and remain a testament to the potentials of man, should be made available for generations to see and be inspired by. Though restoration, documentation, and preservation has improved greatly since Fawcett’s 1987 paper (which is focused on cathedrals in England), like her, I remain troubled about the future and continued authenticity of these structures. By authenticity I mean a time may come when through years of restoration, what we may be left with is an entirely new structure which is only a replica of the original. Chip by chip over the years due to wear and tear, we may completely erase and replace the original for an alternative without even knowing. Philosophically this appears to be inevitable and imminent; my real fear is that the crowd ‘footprint’ may catalyse the process.

A question comes to mind here: at what point does the Parthenon in Greece, for instance, with all the reconstructive elements and placements stop being the original Greek Parthenon of the goddess Athena and starts being a sublime replacement?

Fig. 15: Well, I bought a ticket online two days before, but that didn’t stop what I was to meet inside—more people. Here, inside the Vatican Museum. To concentrate on the beauty of the art in the museum is a little tough, particularly with the huge number of visitors.

Fig. 16: A tourist striking a pose to gesture holding up or pushing the tower of Pisa back into position. These type of photos are very popular with tourists visiting the Tower of Pisa. When one takes the photo of the individual from another angle however, it becomes an interesting and often hilarious depiction of people acting strange.

Fig. 17: A view of the Colosseum with tourists taking photos.

Fig. 18: Cathedral of Florence. Notice the people at the base of the cathedral.

Fig. 19: Tourists inside the Cathedral of Pisa.

Fig. 20: We come, we touch, we tread and we degrade—the impact of tourism on heritage sites isconcerning and far from solved. People inside the Rotunda—The Pantheon in Rome.

The Rome I Saw

They say there are two Romes; the one the tourist sees and then the real Rome. I do not mean to pretend like I am clueless as to what this means but perhaps because of the focus of my study, I saw mostly the tourist areas and needless to say, it was simply beautiful. I had received several warnings before entering the country from friends to be very cautious and weary of the people in Rome and Italy in general. To my relief, I had nothing to worry about in the end. A lot of the people I met and interacted with, from the police at the airport to the lady at the corner shop, were all very helpful and pleasant. Of course, this is not to say that absolutely everyone in these places were pleasant. In many of the sites I visited, I often stood out and got a lot of (unwanted stereotypical) stares, but when the circumstance brings about an actual interaction, many are shocked that I speak English and that I am in fact a university teacher.

Speaking of sites in Rome, naturally Saint Peter’s Basilica was my first port of call. The basilica building and indeed the whole of the Vatican space leaves you with no doubt that art and architecture are extremely potent instruments to propagate an idea, in this case, faith. Details of the mesmerising experience I had with the architecture will be discussed in my next article. One thing I am eager to mention is that through the instrument of sculptural art and ornamentation, the Vatican has left no room for doubt as to who is in charge—one will find the papal insignia everywhere and on everything, even when you are not looking and when you are in fact looking, it is amazing how many you will find around. This constant visual repetition becomes a very powerful communication that unconsciously upholds the order and hierarchical structure of the land. In Rome, I saw that sculpture and architecture are in the very center of the socio-religious message.

Fig. 21: Details of one of the statues at the fountain in the Piazza Navona. Notice the Papal insignia on the upper part of the photo. The two keys crossed beneath a Papal tiara also called a triregnum.

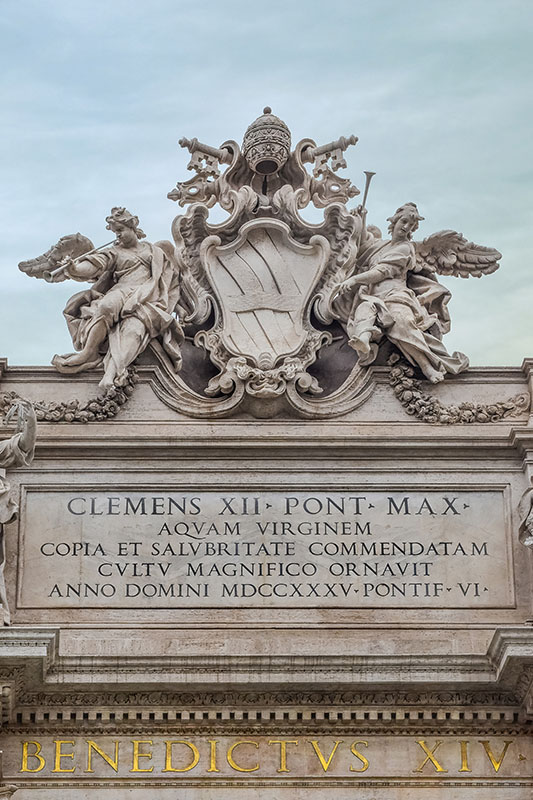

Fig. 22: Again, the crossed keys underneath a triregnum, the Papal insignia as seen at the topmost part of the Trevi Fountain in Rome.

Fig. 23: Over a door way inside the Vatican Museum, notice two Papal insignia—one is gilded and is positioned just under the blue plated sign that reads GREGORIVS XIII PON. The other just above the stone carved emblem.

Fig. 24: A full frame of the earlier featured statue at the fountain in Piazza Navona.

Fig. 25: Another statue at the Piazza Navona, here a male figure is seen wrestling with an octopus. The gull perches on top the figure’s head.

Fig. 26: Saint Angelo Bridge built by Emperor Hadrian. The bridge is directly in front of the Sant’Angelo Castle. The castle is a 2nd century cylindrical castle now museum.

On the Trevi Fountain and the Pantheon

Once you get past the crowd and you freeze the noise, you will at once notice that the design of the Trevi fountain is an absolute evidence of the masterful craftsmanship in ancient Italy. It was designed by Nicola Salvi after controversially ‘winning’ a competition.2 Salvi started work on the fountain in 1732, though the fountain was later completed by Giuseppe Pannini in 1762, as Salvi died before completion in 1751. The Trevi fountain is to me a marriage of stone and water, two naturally immiscible materials, but here presented emphatically as one. The niche in the center with the majestic freestanding columns beautifully frames Oceanus—god of all waters and the Titan lord of the seas. Notice how movement and fluidity is represented in the abstracted clam shape at the base of Oceanus.

On to the Pantheon, and its glory never seems to wane. How do you visit Roma without seeing the Pantheon, the ‘roman centurion’ I featured above told me, “Be a man, brave the cold,” he says mostly by body gesticulation. So, I did brave the cold and walked from the Piazza Navona through the streets with the help of a map and many kind police officers that dotted every major cross point. The temple continues to draw a crowd even almost 2,000 years after its construction. It commands quite a presence within the tight square it now finds itself at the Piazza de la Rotunda. The triangular pediment slightly hides the dome structure from the outside but do not be deceived, the full splendour of the dome becomes apparent as you enter the Rotunda. Partly what draws one to domes are the elaborately decorated inner core—the dome of the Pantheon, in spite of its plainness (coffered concrete with simple geometric patterns), remains as stately as any of the greatly decorated domes.

Fig. 27: The full frontal view of the Trevi Fountain in Rome. Here I have eliminated all human distractions so that focus is on the masterful piece. Notice the fluidity of form at the base of Oceanus—the lord of all the seas.

Fig. 28: Details of the sculptural representation of Oceanus carefully framed by the niche.

Fig. 29: The frontal façade of the Pantheon showing the fountain of the Piazza de la Rotunda in the foreground. Notice the Egyptian style obelisks similar to the one at the Piazza Navona.

Fig. 30: The fountain at the Piazza de la Rotunda in front of the Pantheon. Notice very closely the Papal insignia on the emblem attached to the base of the obelisk.

Fig. 31: A view of part of the coffered dome and the oculus of the Pantheon and part of the apse inside the Rotunda.

Fig. 32: An altar inside the Pantheon.

Florence and the Dome of Brunelleschi

In Florence, one finds one of the most prestigious architectural heritage sites of Italy, the Cathedral of Florence, dedicated to the Santa Maria del Fiore. An impressive piece of architecture that spots what is probably the most popular dome in the whole of Western Europe—Brunelleschi’s dome. The dome crowns the cathedral with all glory. The beautiful cathedral we see today is the culmination of several artists and artisans though it was started by Arnolfo di Cambio in September of 1296. Arnolfo died in 1302 and Master Builder Giotto took over. Brunelleschi won the competition to build the dome over the finished cathedral in 1420 and through years of relentless work and innovations, the dome was finally completed in 1434 and this paved the way for the cathedral’s consecration in 1436—140 years after it had been begun.

Florence has a long and chequered history of social and political turmoil. It was first besieged, though unsuccessfully, by the Ostrogoths around 405, then, the Byzantines in 539 and the Goths in 541. Much later, infighting and clashes between factions—the Guelghs, followers of the Pope, and the Ghibellines, the supporters of the Emperor—raged for years, fracturing the very structure of Florence’s political stability through to the mid-13th century. Interestingly, all the unsteadiness was not enough to dowse the flourishing arts and literature of the land. Some of the world’s greatest artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo worked in Florence when it was at its peak. As it was in the ancient times, so it is now, the sight of the dome will arrest your consciousness. My default practice is to walk right to the center and look directly up into the inner copula, the feeling is the same from dome to dome—such powerful visual expression of beauty.

Fig. 33: Brunelleschi’s dome of the Florence Cathedral.

Fig. 34: A view of the of the cathedral’s bell tower (Giotto’s Campanile). The construction of the tower started in 1334 by master builder Giotto. The tower stands at about 265 ft high.

Fig. 35: A view of the Florentine Baptistery also known as the Baptistery of St Giovanni. The octagonal baptistery is situated directly opposite the Florence Cathedral.

Fig. 36: Details of the front façade of the Florence Cathedral showing the west door and ornamentation. This 19th-century façade was designed by Emilio de Fabris.

Fig. 37: The central western door of the Florence Cathedral.

Fig. 38: Details of a sculpture and decorative elements on the western façade of Florence Cathedral.

Fig. 39: A view of the western façade showing its ornamentation and part of the rose window.

Fig. 40: Inside the Cathedral del Fiore. A view looking towards the altar and a hint of the inner dome.

Fig. 41: Looking up into the inner copula of Brunelleschi’s dome inside the Cathedral del Fiore. The mosaic we see today was done after about a hundred years of the completion of the dome by Vasari, the famous artist. Vasari, on the order of Cosimo I de’Medici, worked on the fresco from 1572 until his death just two years after. The fresco is a representation of the Biblical Last Judgment.

Fig. 42: A view of part of the inner copula of the dome and the altar.

Pisa

I made my way to Pisa, a quite small town roughly 80 km from Florence, to see the famous leaning Tower of Pisa. It was indeed worth the while. The tower, simply known as Torre di Pisa, is actually a detached bell tower of the Pisa Cathedral. The cathedral, a baptistery, and the bell tower are all situated in a spacious square called the Piazza del Duomo. The characteristic tilt of the tower is a result of building on weak soil. The tower was built in phases over two centuries and initial construction work started in 1173. The fault started becoming apparent in 1178 and by completion in the 14th century, the tower had sustained a tilt of about 5 degrees giving an approximately 12 ft displacement of the topmost part. Nevertheless, and in fact probably because of the fault, the fame of the tower has grown immensely. In spite of the tilt, the over 185-ft-tall structure maintains a dignified aura and has remained a wonder to see. As I made my way up the spiral stairs of the tower to see the massive tower bells at the top, I could not help but wonder if these are the same steps used by the famous Galileo Galilei as he made his way to the summit of the tower for his famed experiment on mass and speed of descending objects.

The tower, the cathedral, and the baptistery all in the complex were designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987.3 Recent efforts by modern engineering has now stabilized the tower at least for another 200 years they say.

Fig. 43: The famous leaning Tower of Pisa. Due to soft base soil beneath causing an approximate 5° tilt, the building gave way gradually over the years to its now iconic position.

Fig. 44: A view of the tower with its characteristic columns.

Fig. 45: Details of columns on the Tower of Pisa.

Fig. 46: I wonder if Galileo Galilei went up these same steps for his famous experiment. One gets a floating feeling as you climb the stairs moving from the low side to the high. A slight centrifugal force continues to tug on you until you reach the summit.

Fig. 47: The tip of the tower with tourists to scale. Notice the bells on the tower top.

Fig. 48: One of the bells at the summit of the Tower of Pisa.

Fig. 49: The Pisa Baptistery of St John. Said to be the largest baptistery in the whole of Italy.

Fig. 50: Floral and figural ornamentation on the portal of the main entrance of the Pisa Baptistery.

Fig. 51: A view of the Cathedral of Pisa. Also known in Italian as Il Duomo di Santa Maria Assunta. It is a Catholic cathedral dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

Fig. 52: Details of the columns on the western façade of the Cathedral of Pisa.

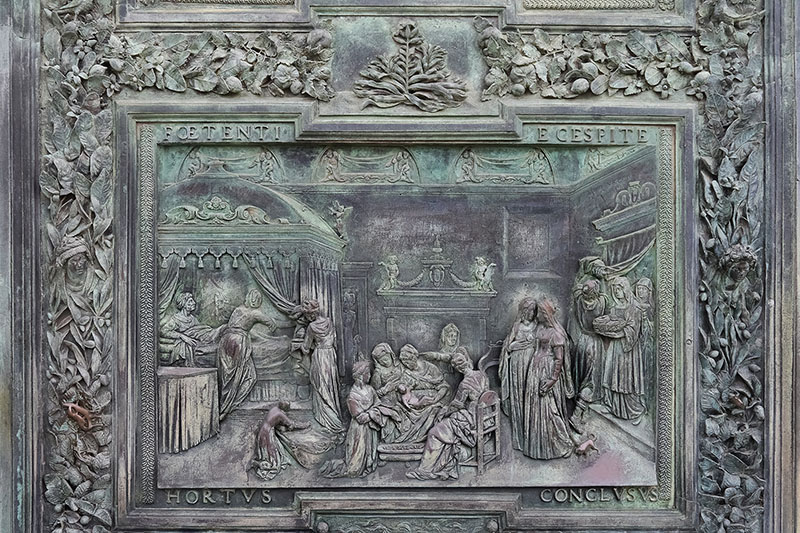

Fig. 53: The bronze central door of the Cathedral of Pisa’s western façade.

Fig. 54: Details of the bronze central door on the Cathedral of Pisa’s western façade.

Fig. 55: Details of the bronze central door of the Cathedral of Pisa’s western façade.

Fig. 56: A view of the interior of the Cathedral of Pisa looking towards the altar from the nave.

Fig. 57: A view of the interior of the Cathedral of Pisa showing columns that demarcate the nave from the northern isle.

Fig. 58: A curious bronze sculpture on the grounds of the Piazza dei Miracoli which means Square of Miracles—this is where the Pisa Baptistery, the Cathedral of Pisa, and the Tower of Pisa are situated. The square is also known as the Piazza del Duomo. The sculpture appears to be of an angel with broken wing.

Fig. 59: The reverse view of the sculpture of the angel with the broken wing.

Fig. 60: A view of the town of Pisa from the top of the Tower of Pisa.

1 Fawcett Jane, “The Impact of Visitors on the Medieval Cathedrals and Abbeys of England” in Old cultures in new worlds. 8th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium. Programme report - Compte rendu. US/ICOMOS, Washington (1987) 876-883.

2 Gross Hanns, Rome in the Age of Enlightenment: The Post-Tridentine Syndrome and the Ancient Regime (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990) 28.

3 "Piazza del Duomo, Pisa". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top