-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

”Seed Crystal” or Cathedral in the Square? Urban Industrial Adaptive Reuse in Contemporary South Africa

When my husband and I disembarked the double-decker city sight-seeing bus at the Newtown stop in downtown Johannesburg, we were the only bus riders to do so. While most other stops we visited on the unmistakable red bus had focused on a single building or experience (Constitution Hill, the Apartheid Museum, the tallest building in Africa), Newtown is a whole “Cultural Precinct” unto itself. On Google Maps, Newtown looks like just museums, theaters, and one or two office buildings. Perhaps implicitly, I was anticipating something like the National Mall—cultural institutions and open space and not much else. But as soon as I stepped onto the pavement and the bus roared off to yet another attraction, I found myself suddenly in the thick of things. Whatever I had been expecting, it wasn’t this. It was an unseasonably warm Saturday in July, and business was booming on the sidewalks of Newtown, a vibrant economy of street vendors hawking their wares to an audience of locals. A few sellers had racks from which to hang purses and bags, but most just spread blankets on the sidewalk. This informal market is a spillover of a larger, and more established clothing retail center further up Diagonal Street, where Helmut Jahn’s monolithic and reflective “Diamond Building” looms large overhead.

Helmut Jahn’s 1984 “Diamond Building” (11 Diagonal Street) quite literally reflects the urban diversity of Johannesburg’s historic core. One of the first major examples of corporate reinvestment in the city center, the building is an unmistakable backdrop to the one and two-story retail structures, such as A. Moosa Blankets seen here, which primarily serve the local population.

As I ventured further, heading down to Mary Fitzgerald Square, I found myself in a very small minority of people who were in Newtown to see the Cultural Precinct. Minus a group of good-natured teenagers who were stress-testing the interactives in the photography exhibit, the Museum Africa was virtually empty. The Worker’s Museum was likewise deserted. There were a few cars in the SciBono Center lot, but thinking that museum had no industrial heritage connection, I opted to skip it. Water bottle running perilously low, I wandered somewhat aimlessly into the SAB (South African Breweries) World of Beer with the thought that I could solve the thirst problem and see some public history simultaneously. The entrance fee dissuaded me, but apparently not a slew of other visitors who emerged from the exhibit hall to collect their complimentary brews on the way out. Ah, this was where the tourists were. With a prominent mention in the New York Times recently updated 36 Hours in Johannesburg, the World of Beer has become the star attraction of the Newtown area, at least for most tourists willing to venture beyond Johannesburg’s more conventional tourism loop.

A quiet day at Museum Africa. The redevelopment of the 1913 Market Hall into Museum Africa (a project conceptualized in 1974 and finally realized in 1994) was one of the first major reuse projects in Newtown.

This whole constellation of museums and theaters represents a decades-long plan to redevelop Newtown following a period of obsolescence and urban decay. Like so many other neighborhoods of Johannesburg, the economic landscape of Newtown was irreparably changed by the institution of apartheid. Formerly a locus of municipal electricity generation, the decline and abandonment of the buildings in Newtown left a major rift in the city’s fabric. Nearby were other struggling areas such as Brickfields (an early “location” for non-whites living in Jo’burg) and Hillbrow (a “gray” area during apartheid that sheltered many mixed race families and was later cut off from municipal services). Newtown, with its existing open spaces and well-preserved industrial building stock, seemed ripe for transformation and renewal that could then spread to surrounding neighborhoods and districts. From the World of Beer lobby, I looked out over the massive project that was meant to be the lynchpin in the new urban plan for Newtown: the former Jeppe Street Power Station. Renovated in 2003 following the design of Guy Steenekamp and Barry van Wyk at TPSP Architects, this award-winning mix of new and old today houses event space, office space, and the AngloGold Ashanti headquarters, and was intended to be a critical and trendsetting piece in Newtown’s renovation.1

A quick snap of the renovated boiler house from across the street. I had been warned to avoid walking around with my DSLR prominently displayed in downtown Jo’burg, and so I ended up with relatively few photographs of my afternoon in Newtown.

Looking back on my time in South Africa, and considering the ways in which deindustrializing, post-apartheid cities are adapting and planning for the future, I have been reflecting on the outsized role that reinvented industrial structures play, both in terms of community function and as signifiers of larger urban renewal. The idea that a single, major industrial adaptive reuse project can meaningfully spark significant commercial and cultural regeneration underpins two major twenty-first century projects in urban South Africa—here, at the former Jeppe Street Power Station in Johannesburg, and more recently, at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art (MOCAA) in Cape Town. Despite hopes that the installation of the AngloGold Ashanti headquarters in the former power station complex might induce a larger commercial reinvestment in Newtown, today it performs a largely symbolic role in its surroundings, exerting a kind of stabilizing influence. Zeitz MOCAA, which opened in September 2017, claims a larger role as a cultural institution in the Waterfront area of Cape Town, aspiring to become the “cathedral in the square” for the newly coined “Silo District” it anchors. While it remains to see how Zeitz MOCAA’s role will evolve in the community, given the project’s siting, as well as its program and current function, there are some conceivable doubts about how it might act as an “urban cathedral.”

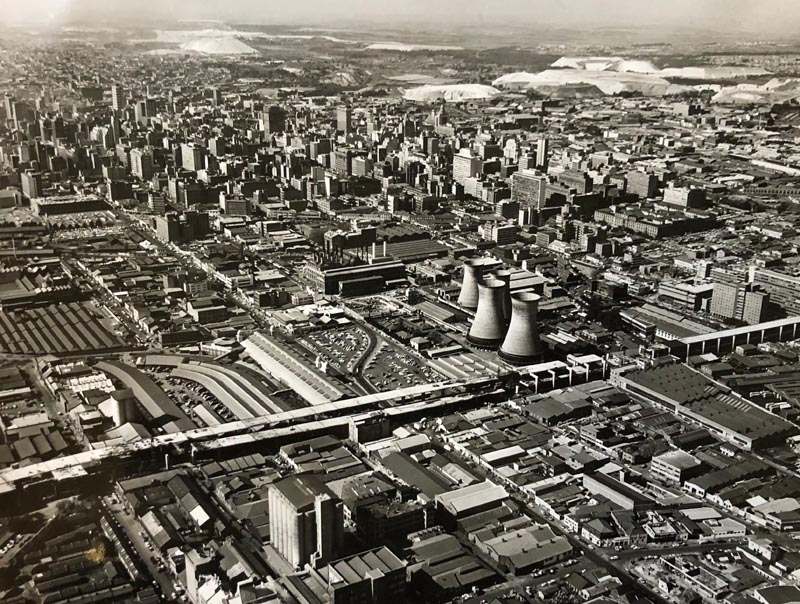

For Johannesburg, like many cities, the period of its most intensive industrialization was also one of centralization, solving the economic and logistic problems of creating infrastructure to serve a growing population by clustering related services and utilities into dense districts at the urban core. Here, the organization of municipal systems and the labor required to build and maintain them was based heavily on existing systems developed in the mining industry for managing labor. In the early days, Johannesburg’s many mines largely generated their own power—power enough to carry out private mining operations but not enough to supply a growing municipality. The city constructed a series of power stations in Newtown beginning in 1892, designing the buildings and their equipment in consultation with British experts. All of this city infrastructure was heavily centralized—Newtown was where the equipment for power generation was located, where the machinery needed to repair existing equipment could be found, and where the skilled and unskilled labor for the power industry were housed (the compound that is now the Worker’s Museum). The electric hub of the city was conveniently adjacent to its main market as well. The sprawling 1913 market hall (now the Museum Africa) and the square in front of it (formerly Market Square, now Mary Fitzgerald Square after the famed woman union activist) were key economic hubs for the city, facilitating efficient trade. Both areas were served by the railroad, which brought in goods and coal to fire the power plants.2

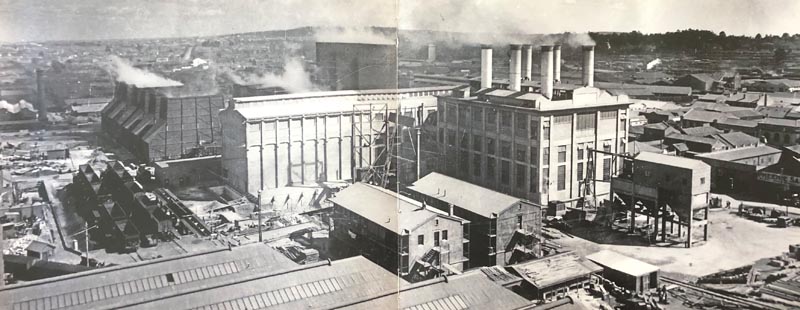

The first power station was primarily intended to supply electricity to the city’s street lamps, but was quickly replaced with a new station (which has been partially reused in the SciBono Center) to serve the demands of the new electric tram system (the tram yard was located in the World of Beer’s present site).3 As demand continued to outstrip supply and the city government of Johannesburg resisted buying power from expensive private companies that supplied power to the mines, it became clear that a third, much larger plant would be necessary to keep the city running. As a result, the city contracted to buy land across the street from the Sanitary & Cleansing Department. This purchase also included a worker compound, that had been constructed to house black sanitation workers in 1913 (what is today the Worker’s Museum). This compound, like the power stations that surrounded it, showed Johannesburg’s continuing reliance on structural and economic models pioneered in South Africa’s mines, that were then adapted to meet urbanistic demands. In this sense, Johannesburg might be considered a city that is uniquely industrial, in a unique and idiosyncratic way. Image sources: (top) Aerial photographs collection at the Architectural Archives, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg; (middle and bottom) scans from Lael Bethlehem, Sue Krige, and Sarah Beswick, Turbine Square: A Heritage of Power (AngloGold and Tiber Group, Johannesburg: 2005).

The first portion of Jeppe Street Power Station came online in 1927, and further additions were made in 1934 and 1939 to meet the city’s ever-increasing demands.4 Its construction came on the threshold of an important change in Johannesburg’s approach to urban planning. As the city expanded, and as South Africa as a whole started to pursue more rigid segregationist policies (ones that would directly set the stage for apartheid), it began to reverse the policies that had previously brought core services (and the people who worked in and maintained those utilities) into the center of the city. Starting in the late 1930s and increasingly following the election of the National Party in 1948, city planners started to encourage decentralization, for instance, building the famous Orlando Power Plant outside of Johannesburg in Soweto (the Southwestern Townships). Townships, as I discussed in my previous post, were the housing areas created to provide a separate, ex-urban living space for black workers. Urban living became the province of the rarefied white elite. (As a side note, planners in Cape Town, and likely other South African cities as well, were influenced in much of their segregationist planning by the writings of Le Corbusier and CIAM during the 1930s and on. The modernist doctrine of separating urban functions, to apartheid’s architects, seemed to dovetail nicely with an ideology that advocated the separation of people according to artificial categories of racial identity.5)

The Orlando station cooling towers, as seen from the Hector Pieterson Memorial in Soweto. Known best in recent years for the artwork decorating their exteriors, the towers are now unfortunately covered in advertising.

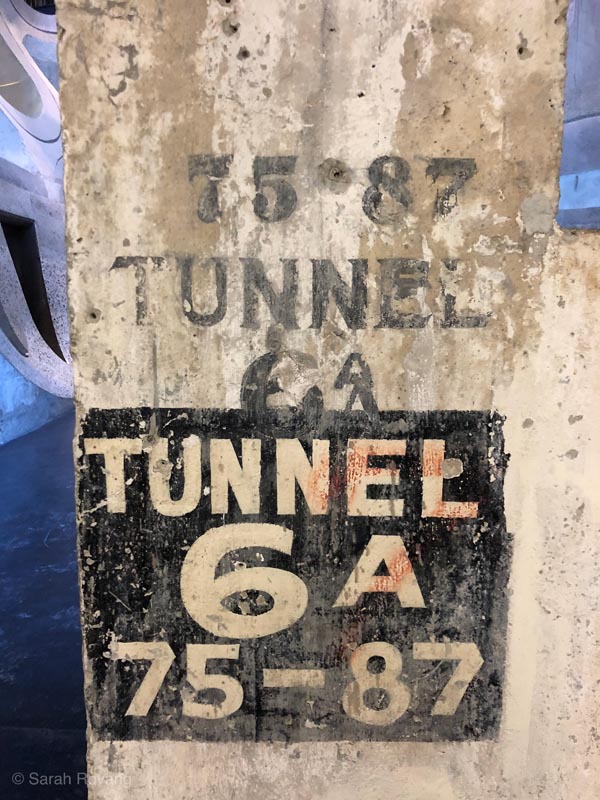

Jeppe Street Power Station, like its predecessors in the Newtown Precinct, had been erected expeditiously and by the 1950s it began to show its wear. In 1958, the original wooden cooling tours were demolished and in 1961 the plant was decommissioned. The rest of the complex was given a reprieve and a second life when in 1966 and 1967, Rolls Royce jet engines were installed to create a backup energy supply for the city. But by the late 1980s, the plant was officially offline once again. In 1985, despite outcry from preservationists and heritage advocates, the cooling towers were demolished. By 2000, it was estimated that there were 300 squatters living in the building. 6

Part of the new architectural fabric of the AngloGold Ashanti building, which replaced the North Boiler House. The sculpture of miners in the second picture is sequestered behind a fence on the company’s private property.

In terms of scale and mass, the power station complex dwarfs the buildings around it—it is the clear visual anchor for the district. On the Saturday I visited Newtown, the buildings were quiet, entirely closed off. I wandered around the perimeter of the building, hoping to get a glimpse inside. In the process of circumnavigating the structures, John and I clearly crossed the line into an urban zone that was not meant for tourists. Unlike the clothing hawkers on Miriam Makeba Street, who were content to ignore me, the gaze on rounding the building was one of the very few places in Johannesburg where I sensed any overt hostility. After a man aggressively begging for money followed us for half a block, we retreated to the patio of the World of Beer on the north side of the complex. From this vantage point, the relationship between the new construction and old industrial structures becomes clearer. On one side is the South Boiler House, which was saved and converted into office space. At the center of the complex is the old Turbine Building, which is currently a venue for hire owned by the Forum Company. To the northern side of the site is a completely new structure built on the site of the former North Boiler House, which contains the AngloGold Ashanti headquarters.7 Tracing the money trail of who owns what real estate within the complex today is an exercise in late capitalism frustration. The industrial heritage of the site has been largely commodified, transformed into a spectacle of “space to empower, grow and enlighten your brand.”8

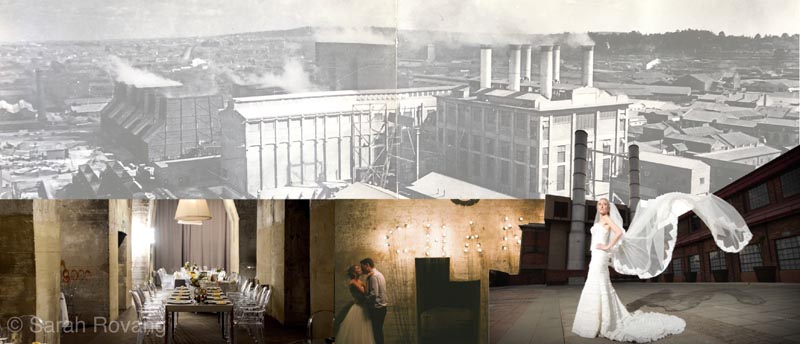

A collage of the transformed event space of the Turbine Building I compiled from a Google Image search, layered over a historic image of the building from its early days. It seems that the Turbine Building has become a popular place to get married in Johannesburg. Historic image sourced from Lael Bethlehem, Sue Krige, and Sarah Beswick, Turbine Square: A Heritage of Power.

With a little more forethought, I probably could have contacted an AngloGold Ashanti or Forum Company PR person for a weekday tour. But in some ways, my unscripted encounter with the building on a Saturday was even more informative. I was experiencing the building like anyone else out on the street, and to me, the converted power station felt distinctly unwelcoming and fundamentally disconnected from the rest of the urban activity, whether local or touristic, taking place nearby. At the same time, the building complex seems to exert a kind of equilibrating influence on the street condition. Far from the archival images of the building from twenty years ago, which show obvious material degradation and broken windows, the South Boiler House and Turbine Building are today in immaculate condition, the end result of a significant public/private investment. I’d argue that the stable presence of the power station even provides a certain kind of reassurance to perspective tourists considering a stop at the World of Beer or the SciBono Center or even the Worker’s Museum.

Even in the 1980s, as apartheid was in its death throes and much of South Africa was in a “state of emergency,” Johannesburg’s city planners and developers were beginning to think about how to revitalize areas like Newtown. With the construction of the “Diamond Building” in 1984, and the subsequent tenancy of AngloAmerican, there seemed to be hope for corporate reinvestment in the city center. However, even after the transition to South Africa’s first democratically-elected government in 1994, squabbles over ownership of the building and funding issues prevented any substantive work from moving forward. By 2003 there had been 30 different schemes for the Turbine building and surrounding area.9

When, finally, plans to move forward with the AngloGold Ashanti project were complete, there seems to have been some conflicting ideas of what the new corporate headquarters would mean for the Newtown precinct. At some points in the planning, it seemed that the developers hoped that the construction of the new building and renovation of the two remaining original structures would spur enough economic activity to drive other corporate investment in Newtown. Other goals seemed less grandiose, aiming, for instance, just to make the white collar employees of AngloGold Ashanti feel “safe” in this formerly troubled urban zone.10

The above collage shows the Turbine Building, which has been converted into event space. Below, the renovated South Boiler House (back, left) and the newly constructed AngloGold Ashanti Headquarters comprise the office space in the complex. Scanned image sourced from Lael Bethlehem, Sue Krige, and Sarah Beswick, Turbine Square: A Heritage of Power.

Even standing across the street at the Worker’s Museum, one can partially grasp how much capital the developers poured into this complex. In this sense, it lives up to one of the original wishes of the Johannesburg Development Agency (JDA), which was established coinciding roughly with the start of with South Africa’s democratic era. The JDA was tasked with revitalizing downtown Johannesburg to make it more attractive to new development. This included providing public funding for current and future cultural institutions, and upgrading overall infrastructure. The agency remarked in 2000 that the power station’s “development will be an important symbol of the progressive realization of the Newtown vision.” 11

But to expect one sequence of conjoined buildings, however large and lavishly refurbished, to functionally reverse the direction of a whole urban precinct, seems a little far fetched, a fact which project architect Guy Steenekamp freely admits, stating that “one site cannot be responsible for all aspects of urban renewal—that it could be a ‘seed crystal’ was something of an idealistic overstatement.”12 Sue Krige of the University of Witwatersrand, who has researched the power station extensively and taught on-site in the Newtown precinct, notes that the relationship between individual structures and the district as whole is often complicated and fraught:

The integration of heritage places and spaces with urban renewal is an uneven process. There is much debate about how an area in which heritage significance resides in the whole (the precinct) as well as the parts (the buildings), may be conserved and re-used sensitively by a set of separate developers.13

And though the power station didn’t spark a wave of commercial activity in Newtown, there’s no guarantee that that more investment would necessarily serve the best interests of the local community. A few miles away in the district of Braamfontein, the popular, vibey Neighborgoods Market caters to a class of trendy millennials and foreign visitors. Another instance of adaptive reuse, in this case a former office building, Neighborgoods has become a kind of magnet for the hipster elite. Change is happening in Braamfontein, which has attracted more retail and restaurants in recent years, but much of this seems more connected to the influence of Wits University and the demands of an active academic community. Neighborgoods seems to be the one stop in Braamfontein for many out-of-town visitors—Uber in, Instagram, Uber out. Into Newtown’s commercial void, by contrast, the sidewalk clothing trade has evolved to serve the people who actually live near the precinct. Like the nearby Fashion District, where a population of Ethiopian immigrants has repopulated and transformed a white collar office district into a bustling maze of multi-story malls and cafés, the Newtown economy doesn’t cater to riders of the red bus or other tourist interlopers. From all that I could see on a Saturday, it felt like there exists a kind of urban détente between the folks who use the street, and the corporate megalith of the former Jeppe Street Power Station. Paradoxically, though the adaptive reuse of the building complex did not become a “seed crystal,” it also avoided the trap of trying to do too much. Whatever (admittedly warranted) criticism might be lobbed at this corporate fortress and pricey event space for perpetuating racial and socioeconomic divisions, this is not a building with a Messiah complex. That fence that keeps the folks on the street out also keeps the gentrification in, creating space for this lively street economy to exist unimpeded by an onslaught of coffee shops and boutiques.

A trendy crowd enjoys live music on the rooftop terrace of Neighborgoods Market in Braamfontein. Only a block or two away, the streets are quiet.

Exploring the Fashion District with Professor Hannah Le Roux, who teaches studio architecture courses at Wits University that engage this part of Johannesburg. Former office buildings and medical complexes have been innovatively reconfigured to meet the demands of Jo’burg’s large population of immigrants from Ethiopia and other parts of Africa.14

At least in the realm of press releases and self-promotion, Zeitz MOCAA, South Africa’s most recent and celebrated example of industrial adaptive reuse, claims to play a more active role in transforming its surrounding urban area. I visited Zeitz MOCAA on a Thursday afternoon, having walked from downtown Cape Town to the Victoria & Albert Waterfront. Quite suddenly, upon crossing the pedestrian bridge over Nelson Mandela Boulevard, the Victorian, art deco, and brutalist building stock of downtown gave way to a wash of new construction. Corporate headquarters and luxury condominums sprouted along decadently landscaped canals in which floated touristy gondolas (and in the nearby harbor, a whole flotilla of private yachts). I strolled past a gleaming office building belonging to British American Tobacco and a Porsche dealership. On the opposite bank of the canal, construction workers were busy with what looked like yet another new, mixed use development. Among all this new construction, however, were scattered built remnants of Cape Town’s old port. The vast majority of this land is owned by a conglomerate called the Victoria & Albert Waterfront, which was “established in 1988 as a private company by Growthpoint Properties and the Government Employees Pension Fund to manage and operate over 100 hectares of prime waterfront land.”15 It is this corporation that also provided the funding for the construction of Zeitz MOCAA.

Real estate development and rapid gentrification in action on Cape Town’s Waterfront.

With the advent of containerization in the 1970s, Cape Town’s port, like many ports worldwide, found itself unable to adapt to the infrastructural demands of larger shipping barges and the adoption of shipping containers.16 No longer able to serve its previous role, Cape Town’s waterfront has been forced to reinvent itself. The former brick power station, built in the early 1880s to house Cape Town’s first dynamos, has been reinvisioned as the “V&A Food Hall,” a phantasmagoria of smoothie bowls and kombucha. Nearby, a warehouse branded as the “Water Shed” has been converted into boutique shop space for local artisans and day-lit co-working spaces. The original crane has been preserved as a visually impressive reminder of the building’s industrial past. The so-called “Jubilee Exhibition Hall” fits nicely with the V&A Waterfront’s larger theme of what might be described as “consumer-centric neo-colonialism lite” (all of the cultural appropriation, none of the calories). The latest and most prominent addition to the retinue of reused industrial spaces in this high-investment waterfront district is Zeitz MOCAA.

The former brick power station that supplied energy to Cape Town’s nineteenth century street lights has been converted into a trendy food hall; an ironically self-aware hipster hotspot.

The Water Shed, a former dockside warehouse, now offers boutique shopping, event space, and co-working opportunities for Cape Town’s entrepreneurs.

Like the Turbine Building looming over Newtown, a fenced and lonely citadel, Zeitz MOCAA stands out in the waterfront district of Cape Town by virtue of its sheer monumental physicality. Visible from almost anywhere along the docks, the museum’s faceted pillow windows sparkle during the day—a lighthouse with many glistening beacons. The glittering windows create a striking contrast to the original concrete of the silos from which they protrude. To paraphrase the project architect, Thomas Heatherwick, “When something is infrastructure, people just don’t look.”17 There is indeed a certain invisibility to infrastructure in the built environment. We become acclimated to it and eventually tune it out as a kind of visual noise. I didn’t start seeing all of the power lines in my quaint Providence neighborhood in grad school until I started writing my dissertation on rural electrification. Heatherwick’s design intends to elevate the original silo, to transform the mundane into something extraordinary. The effect upon approaching the museum is nearly ecclesiastical—the tubular silos have the thrust and verticality of a Gothic cathedral. That initial impression was, I later learned on the building’s audio tour, fully intentional. The master plan for the “Silo District,” the portion of the waterfront closest to the museum, intentionally casts Zeitz MOCAA as the “cathedral in the square.”18 As I walked the building’s entire perimeter, I was impressed at how much breathing room the building has been given—its mass and monumentality could be fully grasped in its urban surroundings.

Zeitz MOCAA stands as a discrete object in the new Silo District of the Waterfront. In the bottom image, note the loading area, which is contiguous with the rest of the building.

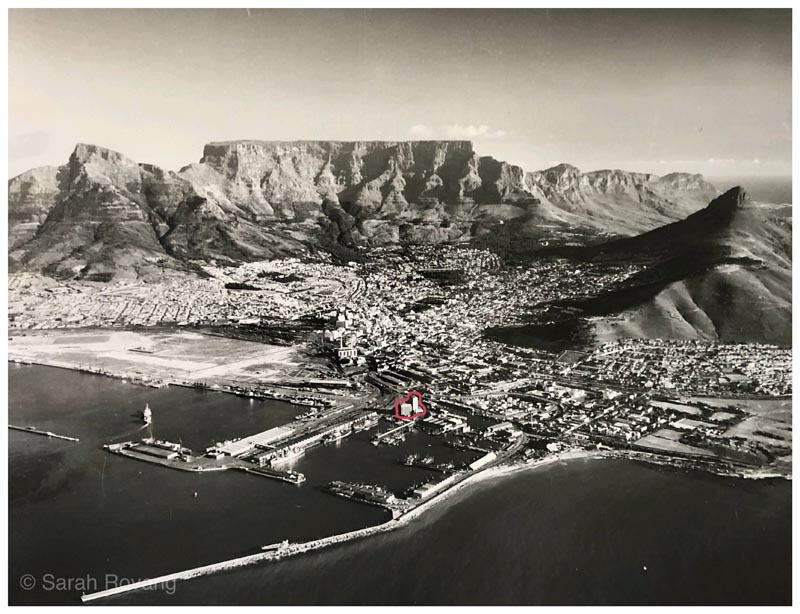

As historian David Worth has documented in his thesis on the building, the silo was originally constructed in the 1920s as a way to provide employment for poor whites, part of an economic development scheme to industrialize South Africa’s agricultural production.19 Like so many development programs in twentieth-century South Africa, the construction of the silo building is shaded by racially-tinged policy planning. In this way, the new use of the building also becomes a kind of restorative justice—by providing a venue for the works of contemporary African artists (many of them black), the building’s original, racially-exclusionary purpose is undermined and provides some modicum of restitution, even if mostly symbolic. Or at least that’s the hope—the museum is named, after all, for the German collector whose long term loan forms the basis of the permanent collection on display.20

A historic aerial photograph of Cape Town, likely dating to the 1950s or 1960s (the grain elevator and silo circled in red). Image source: Aerial photographs collection of the Architectural Archives at Wits University, Johannesburg.

Despite its ample plaza, the silo building is imposing and monolithic nonetheless and a great deal has been done design-wise to make the entrance more human scale and approachable. A shaded patio extends from the elevator building, using an industrial vernacular that seems at home with the rest of the structure. The steel lattice hovers over the remains of recovered industrial machinery. Chairs with conical bases create a kind of silly, haptic play space, contributing along with the patio structure to an effective public, interstitial space between the urban space of the silo district and the interior condition of the museum. On the day I visited, museum visitors and passers-by lolled and rolled on the chairs.

The industrial-inspired patio of Zeitz MOCAA, which creates an interstitial condition and softens the entrance to the building. On the lefthand side (facing the building) is also the lobby of the luxury hotel that hides stealthily in the upper part of the grain elevator building.

I entered and dropped my bag off in a locker room where the original elevator shafts hung from the ceiling. Like the foyer and entry sequence of a cathedral, the building reveals slowly and sequentially the extent and dramatic magnitude of the structure’s inner height. Past the gift shop and locker rooms, the full expanse of the building’s core is finally revealed. The sacred feeling of the core space was further elevated by an operatic sound installation that took full advantage of the silo tubes’ ringing acoustics. I wandered over to the visitor center and picked up an audio tour device. This is the first art museum I can recall visiting whose main audio tour is devoted to the architecture rather than the art.

Entering near the gift shop, the cathedral-like heights of the interior are revealed gradually as the visitor processes into the lobby.

Elevators of Zeitz MOCAA from Sarah Rovang on Vimeo.

From the audio tour, I learned that the museum incorporates three original historic structures—the grain elevator, the silo building, and the dust house. In order to make this space usable as an art museum and structurally sound, the architects needed to replace much of the older, heavy concrete with newer, lighter aggregates. Much of the construction process was in fact one of “excavation,” carving out as much as 80% of the original concrete. The heart of the building itself is an area where the architects extracted a cavity in the shape of a corn kernel enlarged to macroscopic scale. The original concrete is distinguished throughout the building by its lighter hue—the contrast between the new insertions and the remaining material is a sort of visual register of the construction process itself.

Concrete, in all of its finishes and manifestations, is the real star of the museum. The finely polished bottom of the atrium contrasts with the original, rough concrete left in place in the tunnels nearby. The contrast between the new (darker) concrete and older (lighter) concrete creates visual drama and recalls the construction/excavation process.

As I followed the audio tour’s directions, I was led in and out of various galleries, up and down the corkscrew staircase and the tubular, science-fiction-y elevator. One of the largest challenges the architects faced was creating a space where the architecture would not upstage the art. After all, this institution is also the first museum in Africa dedicated to contemporary African art. The solution the architects chose was to create two “separate architectural worlds”—the architectural heart of the building and the art galleries.21 There are a few instances, such as the dust house, where the original industrial, reinforced-concrete interiors of the space have been preserved for site-specific installations. But, for the most part, the galleries follow a standard white cube model. The presence of capital-A Architecture suddenly and intentionally recedes to the background. After the audio tour concluded, I explored the space on my own and found in addition to the obvious visual and spatial differences between “Art world” and “Architecture world,” there were also less perceptible differences that registered in air quality and acoustics. I created the experimental sound piece linked below as a kind of subjective register of that experience. In it, I try to capture the feeling of exploring the galleries, and the refrain of returning to the main cathedral-like core. I also highlight my own complicity in and contribution to the soundscape of this environment, emphasizing camera clicks and footsteps. The source of the sounds is intentionally vague—some come from other video or sound installations, some are HVAC noise, and some are other visitors and docents.

A variety of the interior spaces whose auditory memories are included in the sound piece linked below.

Since Zeitz MOCAA has been open for less than two years, it’s still early to evaluate how the building functions as an urbanistic gesture—how the “cathedral in the square” interfaces in practice with the rest of Cape Town. After I finished my own exploration of the building, I attended a lecture (“Women Making Cities, Cities Making Women”) in the function space on the ground floor. The assistant curator who introduced the program expressed gratification that events like this lecture were bringing in members of the Cape Town community to talk about something other than the architectural space of Zeitz MOCAA. Based on the content of the press hype around this museum, and the architectural audio tour, and this isolated comment, I do get the sense that the architecture has thus far rather overshadowed the curatorial program of the museum. As with the coverage of Turbine Square in Newtown, the majority of commentary about Zeitz MOCAA has focused on the ingenuity of the lead project architects and the boldness of the developers in undertaking such a capital-intensive and financially risky project. A quick browse through the big architectural magazines online reveals lots of interviews with British architect Thomas Heatherwick, but very little mention of the substantial contribution and input from the African architecture firms, engineers, and contractors who were tasked with translating Heatherwick’s cathedral dream into concrete reality. While a sizable plaque in the museum’s core near the lobby lists the names of all of the workers who contributed to the building’s construction, references to the actual human power and skill of the workers who physically built Zeitz MOCAA are notably absent from most mainstream press coverage. As Tomà Berlanda notes in Architectural Review:

At the peak of construction, which lasted 36 months, and 5.3 million man-hours, almost 1,200 workers operated on site. Whereas the official overall budget of 500 million Rands has been quoted as not being much to operate with in other parts of the world for a building and programme of this magnitude, it was ‘a lot of money in the context of Africa’. Credits for the South African local architects and site managers, not to mention the hourly rates to which the budget divided by man-hour equates to, are not easy to find in the official press release, raising the issue of what needs to be done to recognise the African, read black, labour, that allowed the museum to exist. 22

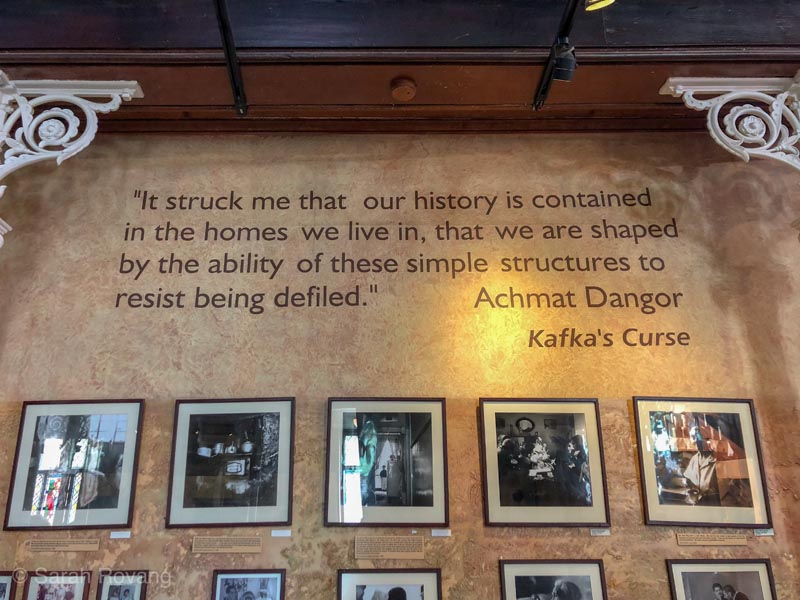

And then there’s the broader question of who the museum serves and how. Throughout my time in South Africa, I was heartened to see community museums and individual entrepreneurs pioneering their own grassroots approaches to public history. Institutions like the South End Museum in Port Elizabeth and the District 6 Museum in Cape Town are actively engaging their communities through art and oral history projects to recover and preserve individuals’ experiences of apartheid and discrimination, and in doing so, are helping to stitch neighborhoods back together across the historic and artificial dividing lines of race. Businesses such as Msanzi Restaurant in Langa, one of Cape Town’s oldest townships, are breaking down the stigma around township living, in the case of Msanzi, by attracting international visitors with the promise of home-cooked African food.

Overlooking the harbor of Port Elizabeth from the South End Museum. The large tree in the foreground is one of the only remnants of a vibrant, multiracial community that was razed under apartheid. The South End Museum now serves as a vehicle of restorative justice and memory within the community.

The District 6 Museum in Cape Town is also an active community organization serves the needs of families displaced during apartheid. Community artists, activists, and historians are engaged in sharing and preserving these memories.

Mzansi Restaurant’s chef and owner Nomonde Siyaka shares her story after a delicious dinner of Xhosa food. Located in the township of Langa outside Cape Town, Mzansi has grown from a single-story, three-room home into a two-story house and restaurant that can accommodate dozens of guests and a live band. Siyaka’s storytelling is part of the experience, bringing visitors into this space and helping to break down the stigma that still exists around South African townships.

As exciting as it is to see a historic industrial building given new life as a cultural institution, Zeitz MOCAA does serve to further the aggregation of wealth and power in the already prosperous and gentrified Waterfront area. Geographically and culturally, the Waterfront is about as far as you can get in Cape Town from the townships, which are sequestered outside of visitors’ views on the other side of Table Mountain. The Waterfront, ultimately, does not need a “Bilbao effect.” This part of Cape Town is doing just fine. In some ways, Newtown and the area around the power station seemed more diverse and inclusive than the “Silo District” around Zeitz MOCAA. While in Newtown, the additional commercial investment that developers hoped would follow on the heels of AngloGold Ashanti never materialized, local people have claimed the streets as their own, and forged an informal retail economy outside the purview of large-scale real estate development. The urban space of Newtown felt lively, occupied by people across the socioeconomic spectrum. Even if Turbine Square hasn’t proven to be a “seed crystal,” it has become a kind of solid anchor for the neighborhood—if Newtown is not regenerating in the way that developers and urban planners had hoped, it’s certainly not regressing either. For the most part, the Newtown cultural precinct seems safe and stable, which is certainly not something that could have been said in the 1980s or early 1990s. In order to have a substantive effect on the wider community and urban condition of Cape Town, Zeitz MOCAA needs to channel its notoriety and expand beyond the concrete hull of its flagship building—it needs to be an institution of outreach and connection.

- Lael Bethlehem, Sue Krige, and Sarah Beswick, Turbine Square: A Heritage of Power (AngloGold and Tiber Group, Johannesburg: 2005). This book is one of the preeminent resources on the redesign and redevelopment of the Jeppe Street Power Station, though due to its writing date it does not contain the latest information on ownership and usage of the building. ↩︎

- Ibid. Also, see my SAH blog post from the previous month for more about the Worker’s Museum and the public history function that it serves. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Information from the District 6 Museum in Cape Town. ↩︎

- Bethlehem, Krige, and Beswick, Turbine Square. ↩︎

- Ibid. The demolition of the North Boiler House was not without controversy and sparked significant pushback from the preservation community. ↩︎

- Jade MacCallum, “Turbine Hall Johannesburg, An iconic heritage building for clients who want to create an innovative event experience,” The Forum Company, 20 September 2017, http://blog.theforum.co.za/celebrating-our-heritage-with-turbine-hall, accessed 30 September 2018. ↩︎

- Bethlehem, Krige, and Beswick, Turbine Square. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid, 47. ↩︎

- Ibid, 135. ↩︎

- Sue Krige, “‘The power of power’: power stations as industrial heritage and their place in history and heritage education,” Yesterday and Today no. 5, January 2010, online version accessed June 2018. ↩︎

- It was Professor Le Roux who very kindly got me access to the archives at Wits University, where I sourced much of the background research for this post. Many thanks! ↩︎

- Tomà Berlanda, “Zeitz geist: Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, South Africa by Heatherwick Studio,” The Architectural Review, 8 January 2018, https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/zeitz-geist-zeitz-mocaa-cape-town-south-africa-by-heatherwick-studio/10026761.article. Online version accessed 26 September 2018. ↩︎

- From the Zeitz MOCAA architectural audio tour, September 2018. ↩︎

- Zeitz MOCAA architecture audio tour. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Berlanda, “Zeitz Geist.” ↩︎

- Zeitz MOCAA architectural audio tour. ↩︎

- Berlanda, “Zeitz Geitz.” ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top