-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Architectures of Wind, Water, and Wood: European Industry Before Steam Power

Sarah Rovang is the 2017 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

On the ground floor of Milan’s Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia is a parade of collection highlights. There is a massive 1895 steam engine named the Regina Margherita and a recreation of an alchemical pharmacy interior. A behemoth early computer holds court nearby. Behind a long panel of glass, there’s a dangling many-armed robot capable of learning from the movements of the visitors who stop to ogle it. The robot watched as I half-heartedly waved my arms at it; it merely shrugged (I later saw it engaged in a merry jig opposite an animated toddler). Right next to the robot display is a hulking Jacquard loom, a room-filling late nineteenth-century contraption capable, with the collaboration of a single human worker, of producing complex textile patterns through an automated process enabled by cards punched with holes that correspond to different mechanical actions. The machine is entirely mechanical, but looking at those punch cards, it was hard to avoid drawing a line to the 1960s computer nearby, and then to the prehensile robot. That was perhaps precisely the point of the display, as now each of these information machines share the same space: the former monastery of San Vittore whose high ceilings and large chambers are seemingly just as suited to displaying the typically oversized industrial items in the museum’s collection as they were to facilitating monastic ritual.

The Regina Margherita, a 1895 thermal power plant that was used to power 1,800 looms in the silk workshop of Egidio and Pio Gavazzi in Desio, Italy.

This Jacquard loom from the late nineteenth century is capable of managing 12,800 warp threads through the use of punch cards while a single worker manages the loom’s weft. The model seen here is notably complex, even compared to other contemporary Jacquard looms.1

When I first formulated my Brooks Travelling Fellowship theme around the “public history of industrial heritage,” I narrowed my selection of sites to those from the nineteenth century and after. I wanted to focus on those sites dating to during or after the industrial revolution, and to spaces and technologies in particular that were influenced by the rise of steam and coal power. It’s modernist hubris though, to think that the industrial revolution was a true break with the past. The groundwork of industrialization, and indeed the architectural and economic infrastructure of the nineteenth century, was laid much earlier in many parts of Europe. In trying to pick up a story that I thought mostly began in the early 1800s, I’ve ended up following threads that wind back sometimes as far as the 1400s.

Within the larger category of industrial heritage sites, those sites which predate the industrial revolution, or which have strong ties to industrial models before the rise of steam power, occupy a somewhat strange place in the cultural imaginary of Europe. There’s something outwardly nostalgic about them—on the surface their built landscapes seem to harken back to “simpler” times. Yet simultaneously, they complicate the easy narrative of global industrialization by showing that complex factory production methods and intensive resource extraction antedate steam power by several centuries.

Further, many of the sites serve as architectural registers for the varied and uneven effects of the nineteenth-century industrial revolution. Some existing industrial sites or regions were almost wholly rebuilt to accommodate steam power, for others the structural changes were minimal and old lifeways and production methods prevailed despite the introduction of new technologies and sources of power. In this post, I examine the architectural legacy of the industrial revolution across three very different sites: Crespi d’Adda, Italy; Idrija, Slovenia; and Zaanse Schans, Netherlands.

Crespi d’Adda: Symbolic Architecture at the Advent of Electrification

Along the banks of the Adda River, about 25 km northeast of Milan, lies the former cotton-mill town of Crespi d’Adda. Built in the decades between 1878 and 1930, Crespi d’Adda sprung from the vision of priest-turned-lawyer-turned-speculator Cristoforo Benigno Crespi (1833-1920) and his descendants.2 Today Crespi d’Adda is both a UNESCO site and an inhabited town, a seemingly dubious distinction for the residents who face an influx of curious visitors during the summer months. When I visited on a weekday in January, I encountered no other sightseers, but the residents did not seem surprised to see a visitor with a camera roaming their streets.

A walk along the Adda River. In the distance, the neogothic tower of the Crespi family castle and brick chimneys of the factory are just visible.

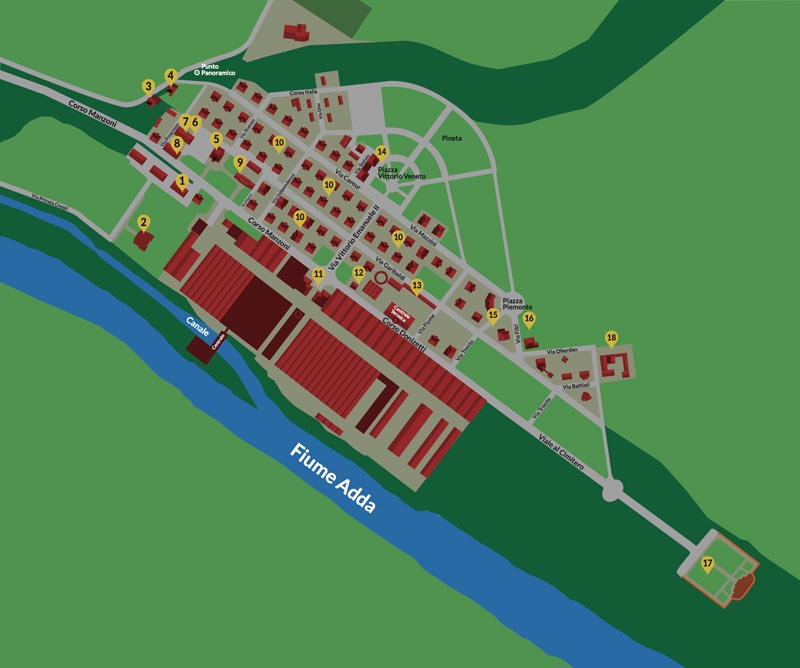

Shortly after arriving, I climbed the Bersò, a steep cobblestone path framed by an arch of hornbeam trees, up to Via Stadium from which a new viewing platform provides a panoramic view of the town. The town follows a nearly orthogonal plan—a slender rectangle laid out against the riverside. Straight ahead lay the regimented rows of worker cottages, near perfect cubes topped with shallow hip roofs, surrounded by invariably tidy and well-kept gardens. Off to the right sat the industrial section of the town, marked most prominently from this vantage point by its monolithic brick chimneys, only paralleled in stature and monumentality by the octagonal church at the town’s center (an exact replica of Santa Maria di Piazza Church in Busto Arsizio, Cristoforo Crespi’s hometown), and the tower of the Crespi family’s ostentatious neogothic castle.3 The only deviations from the Cartesian grid of the plan were the suburban villas for the mill’s executives, which were added later and follow a slightly more suburban layout, and the cemetery, which forms the foreboding terminus to the main street running lengthways through town.

The Bersò, or path, leading up to the elevated Via Stadium, where the homes of the town doctor and priest are located.

Vista from the panoramic viewing platform showing the worker cottages and the industrial area in the distance.

Crespi d’Adda’s church, a duplicate of Santa Maria di Piazza Church in Busto Arsizio, Cristoforo Crespi’s hometown.

The Crespi family villa-castle, designed by architect Ernesto Pirovano and engineer Pietro Brunati, 1893-94. This castle served as the Crespi family summer home from 1894 to 1930. The top balcony, visible here above the high wall ringing the property, provided the Crespis with a panopticon-like gaze over the town and factory. Like most of the other architecture in the town, the power of the Crespi castle is in its forceful symbolism.

One of eight executive villas tucked behind the worker cottages in a wooded area. The villas are notable for their distinctive styles, asymmetrical floor plans, and more suburban siting as compared to the neat rows of worker cottages.

Portentously, the main factory road terminates in the cemetery. From this distance, the foreboding silhouette of the Crespi family mausoleum is just barely visible.

I thought back to the mining town of Sewell in Chile, which I wrote about last month, with its lavish “Teniente Club” and single-family housing for the North American administrators, and simple wooden multi-story apartment blocks for the mine workers. Following the English worker cottages model, Crespi d’Adda quickly pivoted from apartment housing to single family dwellings—an arrangement that was designed to prevent strife between workers and provide the “necessary quietness to rest” but also, we might infer, conveniently impeded worker movements and unionization.4 The Crespi family castle makes the Teniente Club seem restrained and modest by comparison. While Sewell’s architectural hierarchy manifested in terms of scale and placement on the mountain, the whole town—from the director’s house to the lowliest miner’s barrack—was collectively fighting the forces of gravity. The colorful jumble of wooden structures spilling down the mountainside registers less as an attempt to impose order than to merely stay upright. Crespi d’Adda, on the other hand, is an entire architectural universe of ordered life, followed by an ordered death in the rigidly composed cemetery, encoded with nuanced hierarchies that are registered in both scale and style.

It was that vision of order, of a reformed utopian worker community, that motivated the architectural designs of Crespi d’Adda. By the time that Italy began an intensive process of industrialization following Italian unification in 1861, the industrial revolution was well under way in other parts of Europe. Thus Italian factory builders like Crespi already had a range of precedents on which to draw in their designs and layouts. The new “sanitary-philanthropic” model of worker housing introduced by Henry Robert at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London strongly influenced Crespi’s plans, as did built examples such as the town of Mulhouse in France. Other rationalist, utopian precedents included New Lanark in Scotland and Saltaire in England.5 The platonic geometries of Crespi d’Adda and the strident, symbolic expression of stylistic features even recalls the much earlier architecture parlante of Ledoux’s royal saltworks at Arc-et-Senans. Aspiring to expressive architecture rather than archaeologically accurate historicist styles, Crespi d’Adda’s architects, including Ernesto Pirovano (1866-1934), Gaetano Moretti (1860-1938), Pietro Brunati (1854-1933), and Angelo Colla, employ rich detail, varied materials, and vivid polychromy to emphasize the stylistic features of the town’s structures. Although much of the architecture could be loosely described as “Lombardy neo-Gothic” or Renaissance, there are plenty of instances where neo-Classicism and even Vienna Secession peek through.6 Positions higher up in the factory hierarchy meant more elaborately ornamented houses in a wider variety of possible styles.

The first housing built for workers in 1878-88 were these barracks-style lodgings called palazzotti. In the 1890s, under the management of Cristoforo’s son Silvio, the town switched to worker cottages following the model that had been introduced at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London.

The worker cottages, such as this one, follow regular, symmetrical floor plans. The yards were meant to be vegetable gardens where workers could grow their own food.

One of five cottages for clerical workers and department heads. Constructed after World War I, these structures are a testament to the growing managerial class at Crespi d’Adda—one of the byproducts of the expansion enabled by electrification. Their ornament, which picks up elements of the Vienna Secession and even recalls the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright, calls attention to their elevated position above the regular worker cottages. They featured reception rooms and their backyards were intended for recreation.

The onsite signage describes Crespi d’Adda’s cemetery as a “self-contained universe.” While the graves on the left are modern additions, the rigid orthogonal rows of graves marked with crosses are those of former workers.

The Crespi family mausoleum lords over the well-ordered worker graves. Constructed in 1905-1908, the mausoleum was designed by architect Gaetano Moretti in 1896 as part of a competition organized by the Crespi family for this commission. The eccentric stylistic hybridity and diverse allusions of the sculptural reliefs are arguably the culmination of the town’s overtly symbolic architecture.

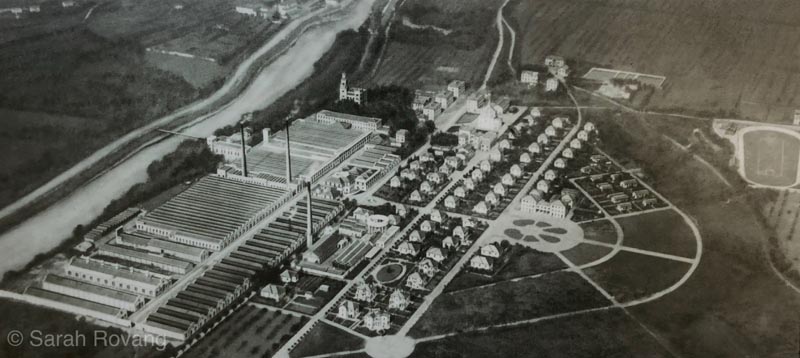

An undated aerial illustration, likely from around 1900. The hydroelectric dam is not shown, nor are most of the executive villas. Image source: “Crespi d’Adda in a Nutshell,” onsite interpretive signage, photographed January 28, 2019.

While many of Crespi d’Adda’s design choices can be attributed to other European industrial precedents, and to Crespi’s own eccentric utopianism, the town is firmly rooted in Italy’s pre-electric industrial past. When the factory was first inaugurated at the end of the 1870s, it used hydraulic energy to mechanically power the devices in the cotton mill. In 1886, Cristoforo Crespi commissioned a thermal power plant, which would use steam power. This new power system allowed the cotton factory to expand from 12,000 to 20,000 spindles. Several decades later in 1909, a hydroelectric dam was built and the operation switched to electricity, which was more dynamic and adaptable to different uses within the factory settings.7 But the idea of building a textile mill using hydropower follows a long tradition in northern Italy.

A few days after my visit to Crespi d’Adda, I took the train to Bologna to visit the Museum of Industrial Heritage there. Housed in a former brick and ceramics factory, the museum’s flagship exhibition shows the development of the silk crepe industry in and around Bologna—a large network of factories that relied on the motive force of moving water to power the mechanisms of vast and complex spinning and spooling machines. In the eighteenth century, as many as 74 silk mills were active around Bologna, along with other hydraulic factories making products such as paper, mangles, and millstones.8 So much of the process of making silk thread was done by water-powered machines, that some aspects only required a lone child supervisor to watch over the machines in case of breakage or error. Early industrialists likewise employed the Adda River for a variety of uses from the 1400s through the 1800s, including textile manufacture, paper-making, and irrigation.9

A scale model of a spindle machine and child worker from the silk factories of eighteenth-century Bologna at the Bologna Museum of Industrial Heritage.

For the Crespi family, who clung strongly to the idea of architectural unity in their plans for Crespi d’Adda, the change in power source did not necessitate an underlying reorganization of the town’s social structure, but merely an expansion of that structure and the factory facilities. Both before and after the introduction of hydroelectric energy, Crespi d’Adda’s positioning along the Adda River was critical—and the historic and technological context of that position remained essential as the company town switched over to a new system of power. The factory complex, which had initially measured 7,650 square meters at the end of the 1870s, expanded to 90,000 square meters by the late 1920s. The pattern of growth was organized to maintain the “overall architectural harmony,” building progressively outward from the original square plaza of the factory designed by architect Angelo Colla, and using compatible Lombardy neo-Gothic style with earthenware ornament.10 Additionally, with the rise of the new hydroelectric facilities, the managerial and engineer class employed by the factory also expanded, reflected in the addition of new houses for middle-managers and clerical workers.

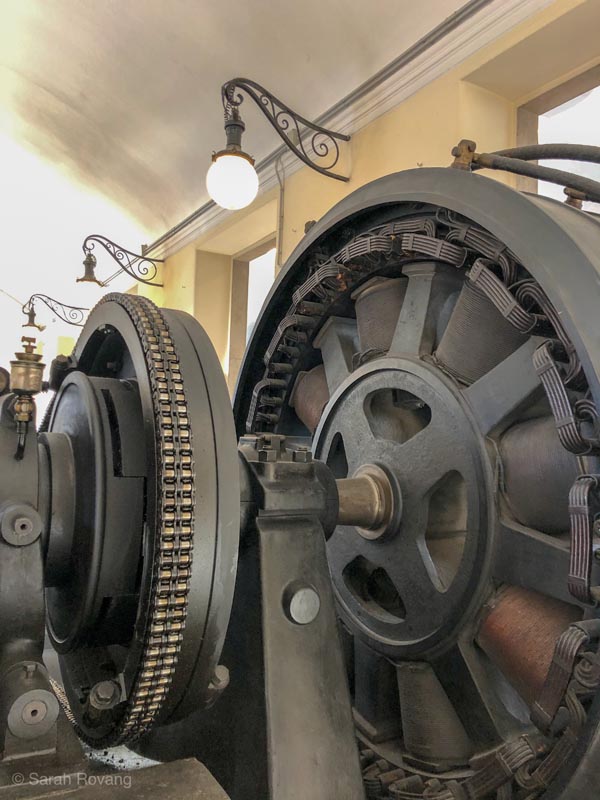

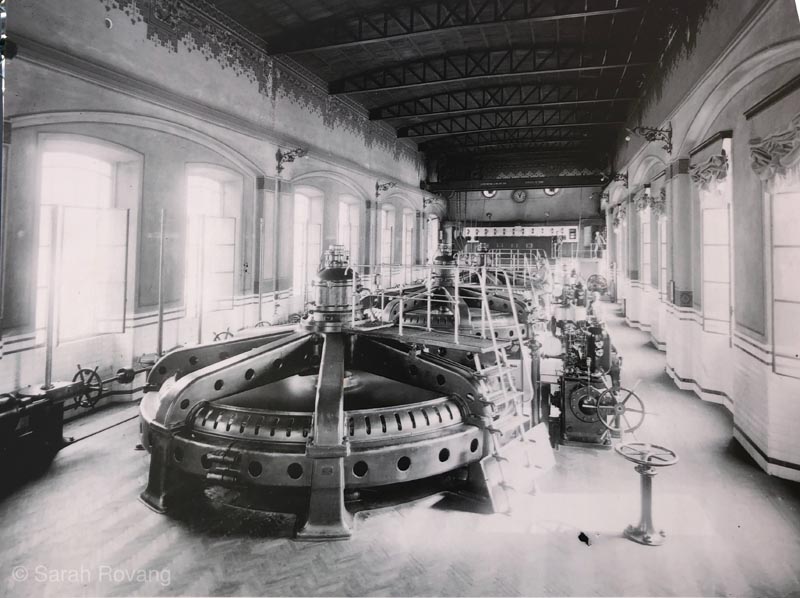

One of the remaining structures connected to Crespi d’Adda’s hydroelectric dam, constructed in 1904.

An archival photograph of the richly ornamented interior of the hydroelectric plant, showing “the importance of aesthetics as well as efficiency.” Image source: “Hydroelectric plant,” onsite interpretive signage, photographed January 28, 2019.

The monumental, symmetrical entrance to the main factory, added following the plans of Alessandro Mazzucotelli in 1925.

The expansive factory sheds are ornamented with terra cotta in the same Lombardy neo-Gothic style used elsewhere in the town.

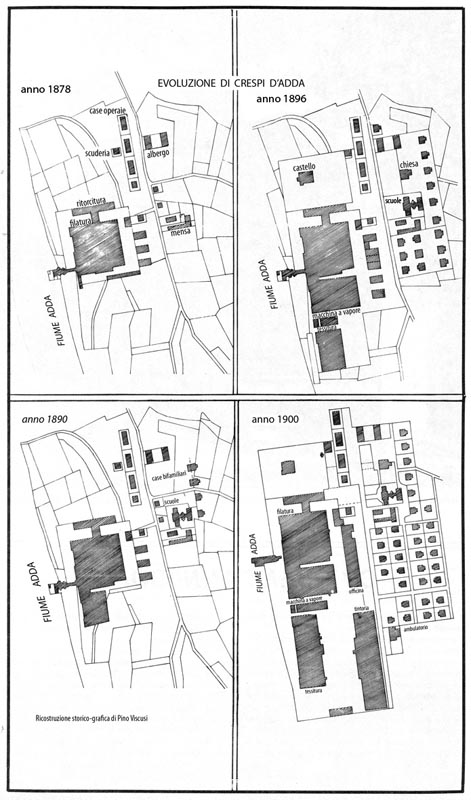

The Four Phases of Crespi d’Adda, plans showing the town’s original development. Image source: “Maps and Drawings,” Crespi d’Adda: UNESCO, accessed February 28, 2019, http://crespidaddaunesco.org/maps-and-drawings/?lang=en

Present day tourist map of the site. Image source: “Maps and Drawings,” Crespi d’Adda: UNESCO, accessed February 28, 2019, http://crespidaddaunesco.org/map/?lang=en

Today in Crespi d’Adda, relics of the factory’s electrified years are integrated into the plan of the town, and have a similar architectural treatment to the older structures that predate them. An electric substation with neoclassic, gothic, and perhaps even Moorish elements has an idealized geometry and solidity to its design not fundamentally different from the church or worker cottages. For the Crespi family, electricity was just another tool that might be employed in the service of their ideal worker community—a mechanism through which the ordered architectural universe might be expanded further.

The electric substation, added after the plant converted to electric energy.

Idrija’s Mercury Mine: The Industrial Longue Durée at a Cultural Periphery

The bus ride out to Idrija from the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana traces a path from bucolic pastures into the dramatic foothills of the Alps. The kozolecs (or roofed hay racks) that dot the agrarian landscape are Slovenia’s most iconic vernacular structure—one Slovenian architecture student I spoke to even showed me his forearm tattoo depicting one. Pretty soon though, the kozolecs disappear, replaced by what Austrians call “the end of the Alps” and Slovenians know as “the beginning of the Alps.”

On the road to Idrija; the “beginning of the Alps.”

Sited among the low-slung mountains surrounding a bend in the Idrijca River, the topography of Idrija lends itself to architectural vistas encompassing five centuries of construction. Near the center of town the steeple of the Church of the Holy Trinity (c. 1500) cuts a distinctive silhouette. Nearby, on one of the hillsides is a sixteenth-century castle—the only Austro-Hungarian castle that never housed nobility. Instead, it was used variously as the mine headquarters and later to store the purified mercury before it was exported to other parts of the world. On another hill rests a former Italian military barracks from the interwar period when the Italians occupied western Slovenia and which is now a psychiatric hospital. Near the hospital sits the picturesque church of St. Anthony of Padua with the Calvary, a 1766 chapel built by miners who manually carried the building materials up the hill.11 On a third is the last of the mercury processing units to be built in Idrija, a facility constructed in the 1960s that operated until the 1990s when mercury production finally ceased. That mercury extraction unit is now part of the town’s UNESCO World Heritage Site along with the main mine entrance and headquarters building. It was there—to the headquarters building at Anthony’s Main Road—that I headed first upon arrival.

Topographic model of Idrija at the town’s Municipal Museum.

This castle dating from the early sixteenth century has been variously used as the mine headquarters and storage for mercury, but today it serves as the Municipal Museum and a music school. The inner courtyard (seen later in the post) shows the eighteenth-century renovations that attempted to bring the castle up to a more fashionable baroque style.

The view from the castle seen above looking down over the hills of Idrija.

View across the Idrijca River of St. Anthony of Padua with the Calvary, on the hillside, with the stations of the cross on the distant hillside behind it.

View of the industrial area of town as seen from the 1960s mercury smelting plant. St. Anthony of Padua with the Calvary is on the nearest hill; the barracks turned psychiatric hospital can just be made out on the second hill behind it.

As visitors begin their tour of the historic mercury mine, they pass through the second oldest preserved mine entrance in Europe. Most industrial mine shafts I’ve been down (which is one of those strange phrases I can use with some authority by this point in the Brooks Fellowship year) are surrounded by conspicuous mining headgear to power elevators and lifts to extract the mined ore. Not so at Idrija—the mine entrance opens directly from out the back of the headquarters office at ground level, separated only by a door. On one side of that threshold is the order and symmetry of the mine headquarters, on the other, a maze of low, dark mine corridors radiating out for several kilometers and penetrating several hundred meters below the earth. The standard miner send-off is emblazoned above door: “Srečno,” meaning “good luck” in Slovenian. The gentle grade of that corridor slopes down to a small underground chapel where sculptures depicting the patron saints of Idrija and miners stand guard to the mine proper. Today only 5% of the original mine tunnels are still open, and these primarily for tourism activities pertaining to Idrija’s “Heritage of Mercury” UNESCO site. The rest have been back-filled with soil or water to slow the subsidence of the town above, which rests directly over the spiderweb of deep tunnels.

The former mine headquarters at Anthony’s Main Road.

The mine entrance at Anthony’s Main Road, which cuts directly from the mine into the hillside behind the building.

The underground chapel where Idrija’s miners would stop to pray on their way to work each day.

After a claustrophobia-inducing hour underground with my very international English-language mine tour group (eight Malaysians, two Romanians, and two Brits), I was glad to be back in the sunshine and fresh air. I wandered up to the Hg Smelting Plant to continue my “Heritage of Mercury” circuit. The tour there followed the course of the ore through the process of extraction, all the way from the top of the plant, where gravity was used to sort and grade the crushed mine ore, down to the massive tube where heated ore was melted to produce mercury vapors, which were then recondensed as purified liquid mercury. On one level of the plant, masking tape Xs dotted the floor—the remnants of the blocking directions for a small production of a Shakespeare play recently staged inside the processing facility. Our guide explained that he has been trying to bring new cultural events into the plant to reactivate the space.

The 1960s smelting plant has been transformed into an interpretive center and much of the original equipment has been retained as part of the UNESCO site.

The smelting plant’s extensive interior is now occasionally being used as an entertainment and community space.

Remnants of the industrial mercury distillation process, these pipes are nicknamed “macaroni” for their distinctive shape. The name is also a reminder of the Italian occupation of the region during the interwar years and World War II, a period during which Slovenian ethnic culture was harshly suppressed.

It’s anecdotes like that that might explain why, even though the mercury production at Idrija has ceased (the EU banned the production of commercial mercury in 2011), this town doesn’t have the same hollowed-out feeling of many other post-industrial communities I’ve visited. There’s a little sadness around the edges—you could hear it in this young guide’s voice when he described the high levels of mercury still in the river and in the bodies of people living nearby. The environmental and public health effects of mercury will still be felt in Idrija for many years to come. However, Idrija is one of the few places I’ve visited where industrial heritage tourism does seem to be palpably adding to the economy and prestige of a post-industrial community.

The lavishly decorated baroque interior courtyard of the Municipal Museum (the exterior of this sixteenth-century castle can be seen above). Idrija’s impressive Municipal Museum housed here recently won an award for being the best industrial or technical museum in Europe. Industrial heritage tourism has put Idrija back on the map since the UNESCO inscription.

The architecture of the area is a bit of an enigma though. Despite the overt modernity of the smelting plant, the rest of the town has a distinctly old world feel. As I walked around the town after the tour, I thought about all of the things that this town has endured in its 500-year history. In contrast to the rapid boom-and-bust cycles of other industrial places I’ve visited, the mine at Idrija has witnessed the Protestant Reformation, the Counterreformation, the rise and fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and two world wars. And over the course of that same half-millennium, the miners of Idrija have used at least six different methods of extracting mercury.12 In the earliest iterations, miners would heat crushed ore in earthen pots, allowing the mercury to pool at the bottom. Later, furnaces using the same principals as a still for the production of distilled alcohol improved extraction rates and made the industrial-scale production of mercury possible for the first time. The final iteration—the 1960s rotary furnace that has is still extant—is the culmination of those many developments.

But for all of the industrial advancement of mercury mining and extraction in the twentieth-century, much of Idrija’s architecture is distinctly eighteenth- and nineteenth-century. During the eighteenth century, extraction technology improved dramatically at the same time that miners were exploiting some of the densest, richest ore. That period of lucrative production spurred the addition of technologically more advanced mine pumps, as well as investment in the public sphere. During the latter half of the eighteenth century, Idrija witnessed the construction of a theater, a grain storage magazine, and new housing—many of these structures reflecting the Baroque styles popular in Vienna at the time. The next great spat of new civic building dates to the end of the nineteenth century, following the Europe-wide fervor for industrial reform (think Crespi d’Adda and its precursors). Many of the buildings dating to this second period of rapid construction pertain to education and the formation of community, including a town hall, a formalized school of lacemaking, an elementary school, and the first Slovenian non-classical school.

Idrija’s 1770 theater building. Foreign troops performed at this theater, and local Slovenian-language productions were also staged here.

The 1764 grain storage warehouse has today been converted into a library, art gallery, and the Idrija War Museum.

This school, constructed in 1876 as the Mining Folk School, still houses educational organizations such as the Idrija Lacemaking School.

Typical worker housing in Idrija dating to the late nineteenth century.

To say that the built landscape of the town depended on the success of the mine is accurate to some extent, but overlooks the nuanced global politics in which the mine was embroiled throughout its history. As Idrija blossomed from a provincial village to an increasingly more cosmopolitan town, it attracted engineers, scientists, and cartographers not just from the Habsburg Empire, which controlled the region for many years, but from across Europe. In addition to its role in an increasingly global economy, Idrija also became a center of lace production. Lacemaking was a vital way for women to generate income in the (sadly likely) event that their husbands died young due to mercury poisoning.

But even with artisanal lace and an itinerant population of educated elites, Idrija remained somewhat of a sociocultural backwater. The town’s relationship with the Hapsburg Empire, and later with Italy, was very colonial—the Slovene ethnic population were viewed as minority outsiders rather than citizens. As the architecture student with the kozolec tattoo told me, “We Slovenians are for all minorities, being a minority ourselves.” That marginal position as a town with a massively valuable resource always on the cultural and geographic fringes of more powerful empires and nations shaped its architecture more than the technological progress of the mine. Idrija’s architecture is less a snapshot of rapid industrialization than a case study in the ways in which an industry changes over the longue durée, and the people and lifeways contributing to that industry change alongside it.

Zaanse Schans: Nostalgia for Wind and the “Invention” of Zaan Architecture

Stepping off the bus at Zaanse Schans, it was the smell that hit me first. If the wind is blowing off the sea—and it almost always is—the odor of Dutch-processed cocoa is unrelenting, punctuated only by an occasional fragrant whiff of marsh and livestock. Along the Zaan River stands a row of historic windmills, and the recreation of a village comprised of historic homes and businesses dating mostly to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Nearby is the Zaanse Schans Museum and the associated Verkade Pavilion, a model of a historic chocolate biscuit factory that smells even more strongly of cocoa than the air outside.

Zaanse Schans purports to be the oldest industrial area in the Netherlands “and perhaps in the world.” While practically every Dutch town historically had a flour mill at its center, the mills of Zaanse Schans used the motive force of wind to power saw mills, paint and oil production, starch refinement, paper making, spice grinding, and of course, cocoa. By the end of the eighteenth century, the landscape was a swirling mass of windmills, following a variety of architectural models. Those windmills kept turning all the way through most of the nineteenth century, even after production rates in Britain, and then in France and Belgium, soared with the adoption of steam power. Eventually, the economic incentives to switch to coal and steam became great enough that new, modern factories joined the windmills along the Zaan and eventually supplanted them. Today, the vista from the viewing platform above Zaanse Schans includes swampy marshland in the foreground, the historic windmills of the recreated historic village in the midground, and the steam-stacks of modern, operational factories in the distance.

The vista from the viewing platform overlooking Zaanse Schans and the Zaan region.

Historic windmills line the Zaan River.

De Kat Windmill, dating originally to 1646 (rebuilt following a fire in 1782). It is the only remaining windmill in the world that manufactures paint. Unlike some of the other models at Zaanse Schans, only the top of this windmill rotates to follow the wind.

The Zaanse Schans living history area is akin to a Dutch Colonial Williamsburg. The historic structures themselves, which include merchants’ houses, shops, warehouses, and windmills, were relocated starting in 1959, as part of a plan by the Dutch architect Jaap Schipper.13 This open-air portion of the site can be ostensibly visited for free, though many buildings, including the larger windmills, cost a small fee for entrance. After struggling with the audio guide app, I gave up and stood in line for overpriced hot chocolate. Screaming children and stoned teenagers thronged through the cheese museum and the goat petting area, so I headed for the less popular merchants’ houses and the clock museum. Later, I climbed up to the platform of a working windmill, whose giant mill stones were furiously grinding flour, and then entered another that was grinding cloves—a fiercely festive scent powerful enough to temporarily overwhelm the ubiquitous odor of chocolate. All these buildings are presented rather uncritically as mimetic architectural manifestations of Zaan culture (and also of historic Dutch culture in general). The level and quality of interpretation in each of the buildings is highly variable—with few exceptions, windmill and wooden shoe kitsch prevails.

The petting zoo attraction at Zaanse Schans.

Outside the Wooden Shoe Museum at Zaanse Schans.

A restored merchant’s house. The status of the original owner and his occupation are communicated symbolically and materially by the ornament around the door.

A combination of house and warehouse, located near the Zaan River to facilitate easy unloading and storage.

Several dozen structures have been relocated to form the “historic” village of Zaanse Schans, including a number of residences, some of which are inhabited.

The blurred inner workings of the spice grinding mill, rotating quickly as the windmill grinds cloves.

It is only the excellent Zaanse Schans Museum, which costs 12 Euros and is accordingly less popular than the “free” area, that acknowledges the way in which the very conception of a Zaan cultural identity was really a reaction to the incursion of modern industry, and to nineteenth-century anxieties about changing lifeways in the region. One exhibit, entitled with intentional irony “Typical of the Zaan Region,” recreates an 1874 exhibition entitled “Tentoonstelling Zaanlandsche Oudheden en Merkwaardigheden” (“Zaan Antiquities and Curiosities”). The exhibit asks:

”What really typifies the Zaan region? Is it the landscape with its little wooden houses? Or is it the people with their Zaan customs, wearing traditional Zaan clothing, keeping their treasures in Zaan-style cabinets? Or is it just a cliché? And if so, where did this cliché come from?”14

Through the reinterpretation of the original artifacts displayed in 1874, the exhibit elucidates the ways in which our contemporary conception of historic Zaan culture was really a construction of the upper classes, motivated by a fear of losing specific elements of material history and intangible folklore to a new era of steam power and mass production. It was arguably that hegemonic vision of Zaan identity that motivated the construction of Zaanse Schans starting in the late 1950s.

The entrance area of the Zaanse Schans Museum.

One of the original artifacts that appeared as part of the “Zaan Antiquities and Curiosities” exhibition. This painting depicts a local legend known as “The Cruelty of the Bull.” It later became synonymous with Zaan heritage, and was reproduced in paintings, on commemorative plates, and other consumer items.

La Zaan-Holland, windmills on the Noorder Valdeursloot, Frans Courtens, 1897. Some artists, like Courtens, focused on the remaining windmills and pre-steam “traditional” architecture of the Zaan region even as new industry began to move in, changing the area’s architectural character.

Factories on the Zaan, Herman Heijenbrock (1871-1948; painting undated). Other artists, such as Heijenbrock, chose to depict the changes to the region, highlighting the transformations wrought by steam and coal.

The Verkade Pavilion, though, at the Zaanse Schans Museum, shows another, equally valid aspect of Zaan culture—that around the industrial manufacture of chocolate-coated biscuits at the Verkade factory. With a strong focus on worker life and the lives of the “Verkade Girls,” this interpretive experience highlights the diversity of the women workers and their experiences. I found myself immersed in a digital game of assembling boxed chocolates off a fast-moving conveyor belt, a frantic and ultimately frustrating experience based on actual historical tasks assigned to factory workers. Later I donned the Verkade factory uniform and posed in front of a giant vat of chocolate. This industrial heritage experience is in some ways more immersive than the “living history” museum outside. Complete with archival corporate materials and oral histories of former workers, the Verkade Pavilion conclusively demonstrates that the formation of Zaan culture did not cease with the purportedly definitive Zaan Antiquities and Curiosities exhibition in 1874. Twentieth-century industrial heritage is as much a part of the region’s history as its eighteenth-century windmills, though perhaps coal-fired steel-framed factories don’t look as good on a commemorative mug.

The exterior of the Verkade Pavilion.

Machinery on display at the Verkade Pavilion, demonstrating how chocolate biscuits are manufactured. The display also features extensive archival material pertaining to worker life and experiences.

The author, dressed for work as a “Verkade Girl.”

Conclusion

At Zaanse Schans, the industrial revolution really did register as a rupture with the past because the replacement of wind power with coal power fundamentally reorganized the architecture and social structure that had been in place for hundreds of years, precipitating a cultural crisis and a desire among regional elites to identify and preserve authentic “Zaan culture”. But at Crespi d’Adda, the pervasive utopian architectural vision of the founder meant that the switch from hydraualic to hydroelectric power didn’t perceptibly alter the town’s urban plan or architectural imagination, merely the scale of production. And in Idrija, town and mine remained connected but ultimately independent architectural identities. The architecture of the town was ultimately more closely linked to the vicissitudes of global empire than it was to the technological advancements of mining and mercury production.

It is perhaps for that reason—that Idrija’s fortunes were tied from very early on to distant global markets—that the public interpretation there also had the largest worldwide focus of all three sites. At the Hg Smelting Plant and the Municipal Museum, Idrija is shown as part of an expansive and complex global trade network as early as the 1500s. In contrast, I was struck at Zaanse Schans and Crespi d’Adda at how local or regional both sites felt in how they were being presented to public audiences. I’ve noted that historical sites that were built during and for the industrial revolution tend to focus more on big, abstract concepts like “labor” and “capitalism.” So it was no surprise to me that “labor history” appeared explicitly in the Verkade Pavilion but not in the open air windmill museum. Even in modern museum interpretation, I think there is a tendency to conflate these pre-steam-power sites with the romance of the preindustrial and the provincial—to focus on ideas like “authenticity” and “place” rather than “capital.” But the potential of early industrial sites like Zaanse Schans and Crespi d’Adda is that they challenge our assumptions as architectural historians and public storytellers, prompting us to go beyond the usual tropes of pre-industrial versus industrial and to see a more complex picture. Getting comfortable with the grey areas of what constitutes architectural “industrial heritage” opens the door to new ways of thinking about the Anthropocene and the shifting present-day landscape of global industry.

- All caption information is from onsite signage unless otherwise noted. ↩︎

- “Cristoforo Benigno Crespi,” Crespi d’Adda: UNESCO, accessed February 24, 2019, http://crespidaddaunesco.org/cristoforo-benigno-crespi-2/?lang=en. ↩︎

- “Architecture,” Crespi d’Adda: UNESCO, accessed February 24, 2019, http://crespidaddaunesco.org/architecture/?lang=en. ↩︎

- “Palazzotti,” on-site signage at Crespi d’Adda, photographed January 28, 2019. ↩︎

- “Models,” Crespi d’Adda: UNESCO, accessed February 18, 2018, http://crespidaddaunesco.org/models/?lang=en. ↩︎

- “Architectural Styles,” Crespi d’Adda: UNESCO, accessed February 18, 2018, http://crespidaddaunesco.org/architecture/?lang=en. ↩︎

- “Hydroelectric Plant,” onsite signage at Crespi d’Adda, photographed January 28, 2019. ↩︎

- “In the Pedini Mill,” onsite interpretive signage, Museum of Industrial Heritage, Bologna, photographed February 2, 2019. ↩︎

- “Context,” Crespi d’Adda, UNESCO, accessed February 24, 2019, http://crespidaddaunesco.org/context/?lang=en. ↩︎

- “Factory,” onsite interpretive signage at Crespi d’Adda, photographed January 28, 2019. ↩︎

- “Church of St. Anthony of Padua with the Calvary,” onsite interpretive signage, photographed February 9, 2019. ↩︎

- These include, in chronological order, burning mercury in heaps, roasting sites, retort furnaces, Spanish aludel furnaces, Leithner furnaces, horizontal and shaft furnaces, Čermak-Špirek furnaces, the modern rotary furnace that can still be seen at the site. Hg Smelting Plant, onsite interpretive signage, photographed Feburary 9, 2019. ↩︎

- “Founder,” on-site interpretive signage at Zaanse Schans, photographed February 19, 2019. ↩︎

- “Homage to Our Ancestors,” Typical of the Zaan Region exhibition, Zaans Schans Museum, onsite interpretive signage, photographed Feburary 19, 2019. ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top