-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Jerusalem Syndrome

As a general note for the reader, the text has been arranged chronologically not as a way defining a hierarchy of importance, but simply in order to condense the complex history of the three religions being studied therein. Similarly, it is important to remember, as we navigate the turbulent waters of Jerusalem’s history, that this is not a text written to promote any contemporary agenda. This is just a humble bit of writing about the way we humans have inhabited space, the significance we have attached to it, and the impact it has had on us.

Figure 1: Entrance to private home in Christian Quarter

Til Death Do Us Part

It is early morning in Jerusalem. An old man walks slowly up the hill to the Lion’s Gate, a small opening in the northeastern side of the fortress wall that encircles the Old City. Just before the wall, a small Muslim cemetery frames the gate, a reminder of the city’s intimate relationship with death. Jerusalem, after all, is where so many people across history have fought to be buried. Behind him rises the Mount of Olives, whose fertile olive groves have over the last 3,000 years been replaced by the solemn stone landscape of Jewish graves. On Judgment Day, it is believed that the mountain will open and the souls buried within will rise up from the earth as the olive trees once did.

Behind the cemetery, past the greater Jerusalem city, is the West Bank, the occupied Palestinian territory from which this old man has come and from which he comes every day. Or, as he told me, “I come to my home in the morning and leave my home at night.”1

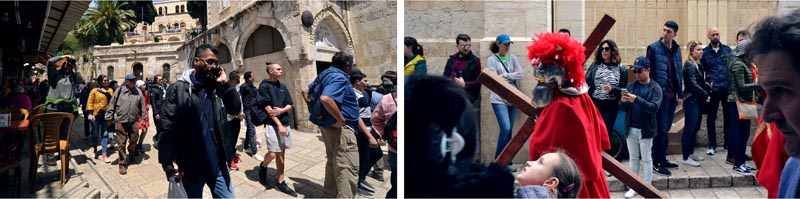

Passing through the Lion’s Gate, he enters into the Muslim Quarter and onto the Via Dolorosa, the processional route that Christian pilgrims take every Easter in honor of the final walk that Jesus took toward his crucifixion. He makes his way slowly, carrying not a crucifix but 60 long years of back-breaking life, a life he shared with this city—whether physically in it or dreaming of it during his 40 years of displacement. When asked why he returns to Jerusalem, he will say, in a tone that is at once stubborn and scared, that this is his home, that here is his history.

Figure 2: A selection of streetscapes from the Old City

He keeps his eyes down, watching each footstep as it falls onto the stone floor. “All these stones,” he says, pointing down at the ground upon which we were so boldly and irreverently standing, “these ancient stones, I love every single one.”2 This kind of love is common here, in a city seen by so many as a salvation, a heavenly gift, and a birthright. It is a love that very easily turns to hate.

He crosses the Old City from east to west, perhaps as an explorer crossing uncharted territory. Or perhaps he crosses as if walking through his own home, comfortably. Or he crosses as if he were a soldier passing through no man’s land, past enemy lines and into a space where he feels he is no longer welcome. Or maybe he just crosses as we all cross space, day in and day out, playing out the small scenes of our lives, choosing to forget the larger drama that is unfolding around us.

He reaches his small store near Jaffa Gate as the first few tourists start their day, cameras in one hand and coffee cups in the other. He hears the sound of glass doors, wooden shutters, and metal blinds as the many store owners around the city open shop. He stands by the door of his store and waits. In no time, the first tour groups will be shuffling through the streets, scuffing up the stone floors, and unwittingly filling in the tense shared spaces that seem impossible to be truly shared by a tightly packed citizenry so fundamentally opposed. And he waits, hoping against hope that they will not notice the tension, the reality, and the inevitability of a city whose very history is a case in point of what will sooner or later erupt. He hopes that the tourists will be comforted by the superficial calm that all the people here keep. Because there is one thing these neighbors share, and that is hope.

And he says, “You asked me before if I have hope. I will tell you. No, there is no hope. But what else can we do but hope?”3

Figure 3: Neighbors, tourists, and pilgrims along Via Dolorosa

Dream Big, Then Try to Go Home

The Jerusalem Syndrome is the psychosis that results when one becomes intoxicated by the Holy City. First identified by Dr. Yair Bar El, this extra-religious reaction reportedly affects roughly fifty persons a year, many of whom are tourists and some of whom have no prior mental illness. So, basically, Jerusalem can literally make you crazy.

Jerusalem Syndrome is described by the historian Simon Montefiore (for those who find the name familiar, the Montefiore name is ubiquitous with the 19th-century urban development of Jerusalem, funded mainly by Jewish investors such as Sir Moses Montefiore) as “a madness of anticipation, disappointment and delusion.”4 More than an expression of religious fervor, the Jerusalem Syndrome is also a coming to grips with reality—the reality of a city that is more than its religious history, a city that is not just an enactment of scenes from the Bible on a loop, a city that is very much living, full of contemporary bits and pieces. One of the reasons Jerusalem has this effect on some is because this city is much more than its physical reality; it is a symbol, a myth, and an aspiration—all bottled up in an impossible ideal.

Figure 4: Panorama of Jerusalem taken from between the battlements of the Tower of David

Humans idealize, they romanticize, and they hope against hope for just a little bit more hope. But, at some point, they are forced to plant that dream firmly on the ground. For many, Jerusalem is that ground. For centuries, this space has been the earthly spot where so many spiritual people across the world have focused their religious ideals. It is the city between heaven and earth, laden with this universal spiritual burden. And, unsurprisingly, these ideals are difficult to reconcile.

Figure 5: Market street scene near Damascus gate, in the Old City of Jerusalem: three Jewish boys buying snacks at a stand owned by a Palestinian

This story can be found across the centuries of this Jerusalem’s history: in the endless list of conquerors, pilgrims, refugees, and of those who ran away when its walls seemed to crumble around them. Jerusalem is a home for people who have never lived there and a birthright for people who were not born there. This is a quality that uniquely marks Jerusalem as a city of displacement, as different groups consider Jerusalem the spiritual nexus from which they have at one point or from another lifetime been displaced. And who is the unlikely culprit of this faith in spiritual property rights? Ancient texts, passed down beliefs, history—the core of several religions.

Reluctant Neighbors

Christ Church was built to resemble a synagogue. So much so that it was referred to as the “Jewish Protestant Church” and was even confused for one by the Jordanian Army in 1948.5 Much like its founder, Michael Solomon Alexander, this Anglican church presents a Christian ideal that embraces and celebrates its Judaic ancestry. As the Church’s website and pamphlet clearly state, Christ Church “fully acknowledges our ancient Jewish roots in its liturgy, symbols, and architecture.” Otherwise nondescript and slyly tucked away near the Jaffa Gate, this Gothic church has an interior that is ornamented with Jewish symbols and Hebrew script and is oriented toward the Temple Mount, as all synagogues in Jerusalem are. Within a city where its various religious sects have always vied for autonomous control, this church stands as an emblem of the harmony that can exist within an uncomfortable, when not aggressive, coexistence.

The three major monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) were born of the same word. The word here of course is the “Word of God,” as written in the Hebrew Bible. A portion of it, the Torah, is known as the Five Books of Moses or Pentateuch by Christians and the Tawrat or Tawrah by Muslims; the Jewish Ketuvim is called the Zabur by Muslims and parts of it, along with the Jewish Nevi’im, can be found within the Christian Old Testament. The Christian New Testament is not part of the Judaic tradition but is referred to as the Injil, or the Gospel of Jesus, within Islam. The Quran is only recognized within Islam and was the last of the three books to be written, postdating the Christian Bible by seven centuries and the Hebrew Bible by eleven centuries. Barring the portions inevitably lost in translation, the additions and omissions from text to text, and the differing degrees of validity conferred upon the writings, it is hard to deny that these three books share a parentage.

Figure 6: Market scene on the steps descending down into the Old City from Damascus Gate

As Heinrich Heine aptly put it, the Bible is the “portable fatherland.” During exile, the Bible allowed the Jewish people to continue practicing their religion without a permanent settlement or a shrine for congregation. But this text did more than allow Judaism to thrive without a physical space of religious power. It had a secondary, paradoxical consequence. The narrative of the Bible is also a narrative of Jerusalem, so the city is entwined irrevocably to the faith as a conceptual icon of that nomadic power. In other words, though all Judaism needed was a book, what it wanted was a city. And with every new monotheistic religion that interpreted the Bible, a new layer of signification was added to the city, simultaneously supporting and challenging the extant ones. Jerusalem itself became one of the links binding these religions together. Like a room shared by too many siblings, the city has had its doors slammed shut and busted open, its floors divided with invisible and visible lines, its walls marred by love-stricken and existential graffiti, and its furniture arranged in every possible configuration—all in the name of a word. The Bible was a catalyst that helped produce an endless cycle of human displacement and laid the foundation for Jerusalem to become a city of displacement.

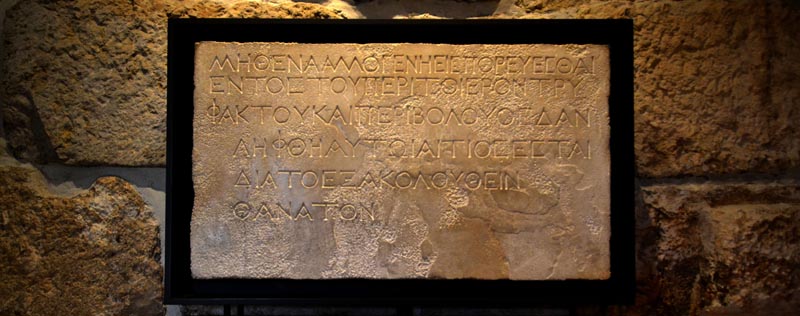

Figure 7: “No gentile shall enter within the partition and barrier surrounding the temple, and whosoever is caught shall be solely responsible to himself for his subsequent death.” (an inscription in Greek concerning the entry into the temple)

A potent example is the Temple Mount, known as the Haram al-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary) to Arabs. (For the purpose of clarity alone, the space will be referred to throughout this text as the Temple Mount.) Journalist Joshua Hammer summarizes its historical significance:

“A territorial prize occupied or conquered by a long succession of peoples—including Jebusites, Israelites, Babylonians, Greeks, Persians, Romans, Byzantines, early Muslims, Crusaders, Mamluks, Ottomans and the British—the Temple Mount has seen more momentous historical events than perhaps any other 35 acres in the world.”6

According to the Bible, the Temple Mount is the site from where God gathered the soil to create Adam, where Abraham nearly sacrificed his son Isaac, and where King Solomon built the First Temple circa 1000 BCE. After the return of the Jewish people following Babylonian-imposed exile in the 1st century CE, they built the Second Temple on this site, reclaiming the land and the power they had once lost. Not only does the Temple serve as a universal symbol of religious power for the Jewish people but it is also a communal space. As Benedict Anderson makes clear in his seminal book, Imagined Communities, “religious affiliation … served as the basis of very old, very stable imagined communities.”7

Anderson explains the significance of religious structures as spaces of individual freedom (entering the temple and taking part in its community is an individual choice), which needed to be curtailed in order to strengthen the hegemony of a state. This is because the religious structure is one of the most powerful catalysts for the development of a community. The architectural structure cements the religious community, just as the text disseminates it. Religion turns abstract faith into anthropomorphized or grounded faith. Within Christianity, for example, the Spirit becomes a Father, prayer becomes Mass, and Judgment Day becomes Jerusalem. The Bible plays a critical role in this metamorphosis, but so does the Temple, and so does the city, both of which take part in the creation of a sacred geography.

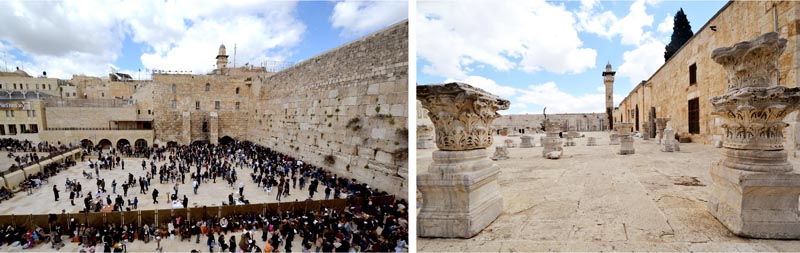

Figure 8 (left) Jews praying at the Western Wall taken from the elevated walkway leading to the Temple Mount; (right) Islamic Museum on the other side of the wall, at the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount.

In 70 CE, the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans quelling a Jewish revolt, leaving only a small piece standing, now commonly known as the Western Wall. This truncated ruin is one of the most significant structures of the Jewish faith and one of the most contested walls in the world. Meron Benvenisti, deputy mayor of Israeli Jerusalem in the 1970s, once asked, “How far [does] the holiness of the Western Wall extend?”

Figure 9: Elevated walkway connecting the Dung Gate to the Temple Mount over the Western Wall Plaza

In 1967, this distance was marked with the exactitude of a bulldozer. In anticipation of the first Jewish holiday after the Six-Day War, Israel demolished the Maghrebi (or Moroccan) Quarter—displacing several hundred residents and razing nearly all of their 135 dwellings—in order provide more space for pilgrims to pray at the Western Wall. Many displaced residents were sent to the Shu’fat refugee camp, the only Palestinian refugee camp located within Jerusalem, along with other Palestinians displaced from the Mu’askar camp in Jerusalem after the Six-Day War. Some of the roughly half who could still trace their parentage back to Morocco went back to Northern Africa.8 In a strange compromise, the urban planners left an elevated earthen walkway over the wall to grant Muslims access to the Temple Mount. What stands today was meant to be a temporary replacement that was installed in 2004 after the first one collapsed. It floats like an enormous centipede curving oh-so-gracelessly over the side of the wall reserved for female prayer.

Figure 10: Western Wall Plaza

So, how far does the holiness of a space extend? This question isn’t asked in order to spark anger or compassion for either side. It is asked because for too long the questions of spatial politics have overshadowed those of spatial philosophy. It is asked because it is a question we should learn to pose and analyze dispassionately. Physically, the plaza in front of the Western Wall is a carving out of space. But that space is imbued with meaning—both religious and political. The carving can’t be described simply as an act guided purely by Zionistic or religious motivation. To describe the creation of the plaza as a solely religious act is to undermine the very significance that space has on humanity and more specifically on the people of Jerusalem. Its significance is like power: it needs to exist on multiple levels in order to truly be powerful.

As Tom Abown writes, the plaza before the Western Wall is used “for rituals where religion, nationalism, and militarism converge and merge.”9 This was the case even before the area was cleared out. When the homes of those living in the Maghrebi Quarter were as close to the Western Wall as two passengers in a rush-hour bus, the act of Jewish prayer wasn’t always assured. At times condemned, at times restricted to certain hours and zones, and at other times even charged, the Jewish right to pray at the Western Wall has been at certain points in history contested by the anti-Semitism of those in power.

Again, this isn’t a solely Jewish truth. This is and has been the case for all religious groups living in the city, made even more complicated by the fact that their claims to the city are much more than purely religious. But, since religion and government in Jerusalem are two sides of the same coin, the city’s history is tainted with an inevitable slew of a hybrid religious-ethnic prejudice and a spatial manifestation of that prejudice. As such, Abown’s statement can be applied to Jerusalem as a whole: the city is a space where religion, nationalism, and militarism have, much like its many inhabitants, always converged and merged.

The notion of self-determination espoused by both Israelis and Palestinians (among others) rests on this complex merging, where neither religion, race, nor lineage can be understood independently. So many feel and believe in their inalienable right to Jerusalem: to own, to return, and to remain within this holy land. And yet, the logic behind this right is impossible to neatly distill for any single group, just as it is impossible to effectively refute.

Take one, take two, and just keep taking

Today, Christians may seem like secondary characters on the edge of the grand narrative being played out between Jews and Muslims. But that hasn’t always been the case. Like the Romani, Slavs, Jehovah’s Witnesses, people with disabilities, homosexuals, and Nazi opponents who were imprisoned and killed in the Holocaust, so many times the Christian Palestinians are overlooked in the study of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. However, they form a distinct minority within the Palestinian Diaspora, having been (most recently) displaced alongside their Muslim neighbors during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Early Christians, who called themselves “The Way,” initially began as nomadic missionaries, “with no abiding city in the world.”10 Ironically, as Judaism became more entrenched in its sacred geography, Christianity claimed the itinerant nature that had once been central to Judaism.

As we all know, Jews would once again be forced into diaspora. Following the Siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, the Romans expelled the Jewish citizens and entirely rebuilt the city in the Hellenistic image, renaming it Aelia Capitolia. They built temples, one to Aphrodite, another to Jupiter, on the former site of the Second Temple, carving out their own space in this sacred site. While some within the Jewish community had a crisis of faith at this loss and turned to paganism, others hung onto the scripture and the family home as the diasporic nexuses of their faith.11

Figure 11: Lutheran Church of the Redeemer

The simultaneous Christian diaspora (back then Christians were still considered by Romans as part of the Jewish community), though also an outcome of forced displacement, may have actually aligned with the group’s deliberate estrangement from Jerusalem—and Judaism. As Karen Armstrong writes, “Jerusalem was now the Guilty City because it had rejected Christ.”12

The Christian return to the city of displacement occurred in the 4th century, when the Roman Emperor Constantine gave Christianity its first taste of power, declaring Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. Since Christianity was supposed to be the link that would bind Constantine’s Roman Empire, the emperor marked Christianity’s rise to power by destroying the pagan temple of Aphrodite, then executing a series of religiously motivated excavations in its place, and building a basilica on the site.

Figure 12: Cupola of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

So, history gives us yet another carving out of sacred space. And Christians flocked to the city from all across the Roman Empire in order to fill in this new gap. Among the new arrivals, there were refugees from the parts of the empire being attacked by Germans and Mongolians. As Armstrong notes,

“The position of the Jews seemed hopeless. The Christians had appropriated their scriptures, called themselves the new Israel, and had now set about annexing the Jews’ Holy City through an imperially funded building program.”13

Now, to the well-informed reader of current events, does any part of this abridged history ring any bells? Church bells, perhaps? Or maybe what you’re hearing is actually the Adhan, or even the Barechu? At a certain point in history, each and all of these peaceful calls to prayer have sounded like powerful territorial markers. Because even architects have to acknowledge that there is more than one way to define a territory.

The Christian prosperity under the Roman rule was short-lived. By 638, Jerusalem had come under the rule of the Arab Caliphates, and the city experienced an epoch of relative religious tolerance. It wasn’t until the end of the 11th century, the end of the First Crusades, that Christians reclaimed a foothold in the city, at which point the building program was renewed.

Each time Christians retook the city, they focused on filling the city with Christians, who, in turn, filled the urban fabric with churches. Then, like rival political parties taking control for too short a time to make any lasting change, conquerors during the Crusades, both Christian and Arab, rushed to rebrand the city in their image only to have those brands dismantled by the next conqueror. Crosses came up on the Temple Mount only to come back down; churches were built up in the streets only to be torn down.

Figure 13: Pilgrims praying at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Students of history will see the gradual emergence of patterns in human actions. The never-ending chronology of names, dates, and border lines can blur together to reveal broad conceptual nuances that, once noticed, seem to tinge all the details like a filter applied over a photograph. There is nothing curious about these repeating patterns: they are the clear manifestation of spatial philosophy, which transcends the details of individual groups, times, and conditions much in the way that human faith can transcend the individual elements in the human world. There is something Darwinian in these patterns: the oscillating line adapts to survive, contracting inward under duress, then fanning out in times of power. Much like capitalism, or tulips.

Our House, in the Middle of…Your House

“Nothing makes a place holier than the competition of another religion.”14

Of course, it doesn’t always start out as competition. When Arabs took Jerusalem from the Byzantines, they still considered Islam compatible with its fellow monotheistic religions, Judaism and Christianity. Muhammed was a prophet of Islam, just as Moses was one within Judaism, and Jesus was one within Christianity. Islam was originally based on the notion that the sanct did not reside in any exclusive space. In other words, the Islamic holy was originally entirely abstract; it had no anthropomorphic or spatial hierarchy of sanctity.

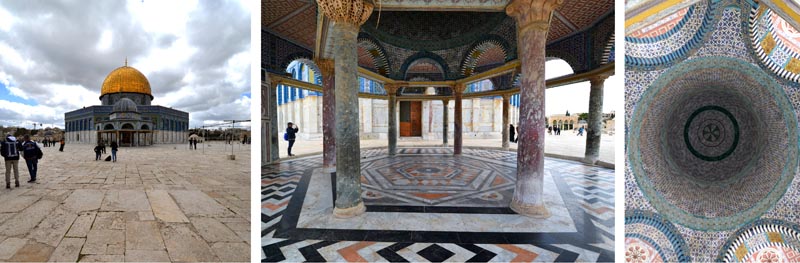

Figure 14: (left) Dome of the Rock and Dome of the Chain; (center) interior view of the Dome of the Chain; (right) view up into ceiling of the Dome of the Chain

Jews were allowed to return to the city and coexistence among the Christian majority and the Muslim and Jewish minorities was, if not harmonious, at least effected. At first, Muslims even prayed facing Jerusalem, as a symbolic gesture of solidarity. Islam soon learned the significance of materializing the abstract, at least in terms of architecture. (For Muslims this materialization was funnily enough quite abstract, as figurative images were denounced to avoid becoming objects of worship.) In Jerusalem, Muslims built the Dome of the Rock, where

“The Rock and its cave symbolize the earth, the origin and starting point of the quest. It is surrounded by an octagon, which, in Muslim thought, is the first step away from the fixity of the square. It thus marks the beginning of the ascent toward wholeness, perfection, and eternity, replicated by the perfect circle of the Dome.”15

The very building was designed as a path toward the divine, a path that was supported by a foundation of the Judaic tradition—one which the Muslims celebrated. This space aided not only in architecturally materializing the Islamic roadmap to the sacred, but also in the development of a Muslim sacred geography.

Figure 15: Dome of the Chain, in front of the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif is the third most sacred space in Islam. Upon the Mount, the Al-Aqsa (or “farthest”) Mosque, is considered the final destination of Muhammad’s Miraculous Night Journey. Many have questioned the validity of this story, much in the way that many have questioned the existence of the First Temple of the Jews. But, as Armstrong points out, “stories about Jerusalem should not be dismissed because they are ‘only’ myths: they are important precisely because they are myths.”16 Whether or not these spaces are actually the sites of historic events is not what validates their significance; instead it is whether or not the people believe in their significance that validates that significance.

Figure 16: Haredi family walking around the southern edge of the old city on the first day of Passover

We’ve meandered through these ancient streets, stepping now gingerly over these ancient stones, getting lost between the maze of layered walls of history, and passing humbly and, if we’re honest, a little nervously through the invisible yet oh-so-marked lines dividing this city and its people. We’ve stopped to stare at details, to read inscriptions, and to watch the crowds pass by. And, every now and then, like a string catching the light, we saw it, just a glimmer, revealing something we couldn’t quite grasp. At some point, we came to realize that this single string weaves its way through the entire city, somehow managing to braid itself into everything around us, binding the disparate elements, the disparate people, and even their disparate ideologies.

In this city of displacement, space is a marker of power and architecture is as physically ephemeral as it is conceptually eternal. And that string—that timeline, that family line, that wall, that word—can be as divisive as it is binding. All we can do is trace it back, then trace it forward, and hope that it might one day delineate a common ground.

Jerusalem Stone

The sun begins to set on the wall around the Old City of Jerusalem. The cream-colored stones are cast in darkness and the clouds behind them begin to catch the pastel hues of the Middle Eastern sun. A crowd of people walk leisurely along the outer edge of the wall, the kind of procession that makes one think of a strange blend of afternoon stroll and funeral walk. The men wear dark coats and wide-brimmed hats, their two locks of curled hair coming down to their shoulders and their hands upon strollers. The women wear perfectly coifed wigs and long skirts and hold onto the hands of the few children who are not running up and down beside them, climbing on rocks, benches, and railings.

The wall may be cast in shadow, but it never seems to disappear from view. The people stand out, moving, breathing, and filling out the space beyond the wall, but the wall always looms beside them, guiding them along a path that gets darker with each passing step. Or so it seems, until they reach Jaffa Gate, where tourists, pilgrims, Israelis, and Palestinians weave in and around each other, so easily mingling in the dim light of dusk that you forget they are anything other than human. The procession disintegrates as it reaches the larger crowd and, together with the others, they disperse out into the greater city, disappearing behind those labyrinthine streets of Jerusalem stone.

Next month, we’ll go in search of these estranged humans. Until then, let us look up to the sky once more, and remember that there are some spaces we can still share, if only with a little bit of faith.

Figure 17: South Wall of the Old City with a view of the minaret of the Herodian Tower of David

4 Montefiore, S. (2011). Jerusalem: The Biography. [Kindle Edition] Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

5 Christ Church Jerusalem. (2017-2019). About Us. Retrieved June 11, 2019. http://www.christchurchjerusalem.org/about-us/.

6 Hammer, J. “What is Beneath the Temple Mount?” Smithsonian Magazine, April 1, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-is-beneath-the-temple-mount-920764/.

8 Abown, T. (2000). “The Moroccan Quarter: A History of the Present.” Jerusalem Quarterly File (7), 6-16.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top