-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Building Neverland

Aymar Marino-Maza is the 2018 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Figure 1: Israeli soldiers leaving Jaffa Gate after Yom Hashoah ceremony

I Got Issues. But You Got ‘em, Too.

Breathe in and breathe out. This is about to get a little uncomfortable. Try to get ready. Let the air in. Let it out. Try to concentrate on the movement. It is a movement that we are all so very used to. But it’s a concept we don’t always appreciate. In order for something new to come in, something else has to come out. In and out. It’s a movement we might even take for granted. For those of you who have never had to worry if you’d take your next breath, the movement is easily overlooked. But sometimes this movement isn’t as easy as breathing should be, is it?

When a new people enter a space of power, another people must leave it. In and out. Sometimes this movement only manifests itself as a shift in power dynamics, but other times it’s a physical movement. This can take various forms: as visible as gentrification, as violent as ethnic cleansing, or as irreversible as genocide. Each of these loaded terms has been used to describe the spatial reconfigurations that accompanied the inception of Israel. What we are referring to is the placement of Jews and the displacement of Palestinians within a space with too many names to count, a place I will refer to throughout this text as the Land of Many Names.

On some level at least, both of these migrations were expressions of forced displacement. But defining these displacements isn’t a simple matter. Displacement isn’t just a physical reality; it is also a psychological one. In other words, the feeling of displacement isn’t only defined as being torn from one’s literal home, it is also defined by one’s surroundings and the impact they have on one’s sense of home. As Rana Barakat aptly wrote in her piece The Right to Wait, “I live(d) in Palestine and at the same time I dreamed of a homeland.”1 This is a perfect example of the psychological power of displacement in action, where the physical and the psychological must coincide but need not harmonize.

Psychological power is the ability to manipulate the reality of others, making them believe a certain reality in order to gain a specific response. With this in mind, let us look at a series of spaces that have been manipulated to bring about a psychological reaction from the displaced people who inhabit them. These spaces will be studied through a wide lens of spatial markers, things like urban barriers, keys, street signs, and art pieces, which serve as “psychological manipulators.” This manipulation is sometimes deliberate and political, while other times it is corollary and, of course, also political. Because, when it comes to the Land of Many Names, everything is political. As Ibrahim Abu-Lughod told his daughter, anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod, “As a Palestinian, you can’t escape politics.”2 This is true for anyone who steps foot within this region of the world, as we are just about to.

The distance between deliberate and corollary in this hyper-political space is messy and heated and not the point of this text. So, for anyone looking to read an argument laid out to reveal a well-defined villain, you will be sorely disappointed. I apologize for this in advance, just as I apologize for whatever bias inevitably seeps out through my choice of words. Pathetically, I can’t help my humanity.

Faulty Lines

At 10 o’clock on the morning of the 1st of May, activity in Jerusalem stops. Cars break in the middle of the road, pedestrians stand immobile on the sidewalk, and trams grind to a halt. On this day, Yom HaShoah, Israel honors the victims of the Jewish Holocaust, and Israelis pause as thousands of sirens come together to sing a melancholy song across the country. The breeze still blows and the birds still fly overhead, but humanity, that conqueror of all things tangible, that empress of all things intangible, stops moving for a single minute. Well, some of it does.

Figure 2: Soldiers during the Yom Hashoah ceremony at Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem

At Jaffa Gate, a young soldier fidgets. He’s standing within a rigid formation, surrounded by his fellow men, all of whom seem capable of disrobing their humanity during this solemn moment. But this soldier still hasn’t mastered the skill of standing still. Involuntarily, he turns around. And, well, he’s caught in the act.

But he’s not the only one in motion. The city doesn’t entirely shut down for that moment of silence. Not even in the public sphere. Tourists shuffle around the square, snapping pictures and mumbling into their phones as they videotape the scene. Babies cry over their own (probably) unrelated laments. A car speeds violently past the parked cars on the road that passes under Jaffa Gate, making a show of its movement. It zooms past the crowd along the 1949 Armistice Line, the boundary line that divided Jerusalem and the rest of the Land of Many Names between 1949 and 1967. Called the Green Line, this border was a Middle Eastern version of the Berlin Wall: a national fault line cutting right through a city.

Fault lines are fractures caused by a significant displacement of bodies of mass. It seems an apt image to use when describing the situation in the Land of Many Names. Much like in geology, the creation of a fault line is never the end of the story. Sometimes, what comes next is like water, coursing through the fracture and wearing it down until it’s as smooth as the rose-tinted walls of Petra’s Siq. Other times, though, the fracture can create a new balance, as one of the bodies of mass comes up over the other, pushing the latter down below it.

The Green Line was not a permanent demarcation of a Jewish national border but a temporary one, one that has since been overstepped and disregarded by both the Israeli government and its people. Nowadays, this line is nearly invisible within the urban fabric of Jerusalem, due in large part to this overstepping. Modern structures built by Jewish people line both sides of the byway that has been built along this Green Line. Outside of Jerusalem, more of these structures can be seen farther out on either side of this “invisible border.”3 These structures take on many forms, from small enclaves of trailers to rail lines, highways, and fully developed settlements. The demarcation, though mostly lacking physical markers, can still be seen in certain places as a row of trees. Planted by the Israeli government at the inauguration of that line, it reminds one of the palimpsests upon the façade of an old building. It serves as a living reminder of how much the power of space is ruled by the meaning humans attach to it.

As Haaretz journalist Shakked Auerbach wrote,

“[The Green Line is] transparent for most Israelis, thanks to their government’s efforts to erase it from the consciousness of the country’s citizens. But for the Palestinians, it’s as impassable as a border made of concrete, both as a structure of consciousness and in the form of the actual separation barrier that Israel built in recent years.”4

No structure built by man (or any tree planted by man) is devoid of human meaning. That meaning, while not innate to a structure, has the power to affect us. It’s as simple as seeing is believing. And here’s the scary thing: everything that we see has the power to make us believe something. Now, most of us are not the architects of the spaces that surround us or of the meanings with which they are imbued. All we can control is how we choose to process that meaning and how we choose to inhabit those spaces.

Figure 3: View of Shuafat refugee camp from french hill, Jerusalem

Chosen Trauma

The consequences of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War surpass the demarcation of an easily crossed line. 1948 is also known as the year of the Palestinian Exodus or Nabka. A new order took hold as the Green Line was drawn on the sand, redefining the lives of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians across the Land of Many Names.

An Italian Jew living in Jerusalem under the Ottoman rule once noted, “Here we are not in exile, as in our own country.”5 This similarly paradoxical statement is a succinct subtitle for the complex way people internalize the notion of displacement. Derivations of that same paradox can be applied to many Palestinians today, for example, “Here we are in exile, in our own country.” The complication with the second statement is that it cannot imply another place where Palestinians can replace to, as the Italian implied about the Jewish community. Palestinians do not have another homeland to turn to. And, no matter how many times the “Jordan Option” gets tossed around, it will always be short-sighted, both on the level of international politics and on the level of group myth. (As proof of that, even Jordanians of Palestinian descent are, as of 1988, being stripped of their Jordanian citizenship.)

The reader will no doubt have easily glossed over the word politics and then promptly gotten stuck on the word “myth.” Let’s dissect this word within our current discussion of the psychological power of displacement and use it to introduce the second spatial marker in this text: the key. We turn to a well-known Turkish psychiatrist, Vamik Volkan, who coined the phrase “chosen trauma” to describe the way a group’s past traumatic event can evolve into nationalistic armor. In his words, it works when “the group draws the shared mythologized mental representation of the traumatic event into its very identity,” thereby linking the group together.6

One of the “chosen traumas” of the Palestinian people is the previously mentioned Nakba, which aptly translates to “catastrophe.” Embedded within this unifying traumatic event is the symbolic (and for so many also very tangible) image of the key to the family home in Palestine. The home and its key become powerful only because they are real on a physical level. In other words, calling a specific space in Palestine “home” gives a tangible dimension to the notion of a right to return. But the significance of the image of the key, and with it, the image of the Palestinian home, isn’t just a tangible hope for individual exiles. Since it is a hope shared by so many across the Palestinian diaspora, it serves as a unifying node among a people who might otherwise have very little to bind them back to each other and back to their shared home.

Much like the current spatial and political geography of the Palestinian territories, the story of the Palestinian displacement after the 1948 Palestinian Exodus is multifaceted. There are refugees in camps within Palestine, refugees in camps across the Arab world, internally displaced persons (IDPs) with citizenship in Israel, temporary residents in Israel, and displaced people in the occupied Gaza and the West Bank and elsewhere, notably in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. There are first-, second-, and third-generation refugees. The landscape of Palestinian refugees is highly divided and the experiences of these different people are very hard to reconcile into a singular identity.

Within this landscape, the shared group memory of the key serves as a binding element of cultural heritage for this diverse and heterogeneous group. It complements the notion of a right to return with the powerful mythological weight that only such a simple image can bear. This is not to say that because the unity is imbued with a mythology it is less valid. Any social force that affects the attitude of a group of people is on some level imbued with mythological meaning. This is as true for the Jewish people as it is for the Palestinians. Because, as we all very well know, Palestinians are not the only group with experience in “chosen trauma.”

Figure 4: Israeli flag over Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, Jerusalem

Modern Zionism was established by Theodor Herzl in 1897, a year after his seminal pamphlet Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) was published. Herzl’s text is of interest for this discussion because it naturally bounds together two concepts: displacement and persecution. Herzl wrote:

“The Jewish question exists wherever Jews live in perceptible numbers. Where it does not exist, it is carried by Jews in the course of their migrations. We naturally move to those places where we are not persecuted, and there our presence produces persecution.”7

Though the text speaks specifically of the Jewish people, the marriage of those concepts in that text births here a universal truth, that displacement and persecution are as intimately bound as the chicken and the egg. With this logic, in order to stop persecution, the displaced must carve out a space of autonomous power. Because, as Herzl aptly wrote, “the majority may decide which are the strangers.” However, the outcome of that conclusion being carried out within a land that already has so many names is anything but simple. As most readers know, Zionism evolved organically into a spatial problem. Below we will look at two different instances of how Jewish communities have demarcated a Jewish space within the Land of Many Names.

Figure 5: Haredi man walking in front of the Schneller Orphanage, Jerusalem

Mi Casa Es Su Casa

You’ve got to learn to read a room. And I mean that literally. Rooms, buildings, streets, neighborhoods, towns, cities, and all other built spaces are littered with signs. Signs instructing people how to move about space, much like a script telling an actor how to move about a stage. So, with this in mind, let’s read a couple signs.

Take two very different signs as examples: the sign at the entrance to the Haredi neighborhood Me’a She’arim in Jerusalem and the sign over an Israeli settlement in the West Bank. They are both powerful signs embedded with tradition, but they have very different ways of using that tradition. The respective “ways” reveal something about the different attitudes each group has toward the way space is meant to be used.

Figure 6: Sign in Me'a She'arim, Jerusalem

The message at the entrance to the Haredi neighborhood is written clearly in Hebrew and in English. That is because it is written for the sake of anyone outside the Haredi community. It informs foreigners how they should behave and dress when entering the neighborhood. And it reminds non-Haredim that they are entering a community that exists apart from the rest of the world, acts independently of any government, and doesn’t support Israeli sovereignty.

This Jewish minority flourished at the start of the 20th century in response to the persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe and then was reborn with renewed fervor from the ashes of World War II. The Hasidic community that evolved from this group of survivors is insular and adheres rigidly to a traditional value system and religious doctrine. Set firmly against the outside world, this community retreated into itself on economic, social, and physical levels. While the Me’a She’arim sign is meant to express the Haredi values of public social conduct, it also signals a border. It acts much like a sign reading “Private Property: No Trespassing.”

The signs marking the Jewish settlements across the Land of Many Names are another example of tradition applied to serve the development of a group identity. Much like the signs across Me’a She’arim, these welcome signs are emblems of group power. However, unlike the Haredim signs, these don’t represent a retreat inward, but an expansion outward. The “ravenous wolf,” an emblem of the Tribe of Benjamin, howls over an almost ironically green scenery with pitched-roof houses. And somewhere behind the sign, this cookie-cutter image of this town is materialized like a city upon a hill overlooking an otherwise desert landscape.

A “city upon a hill” is a phrase anyone raised in the U.S. will likely know, though its origins lie in Jerusalem. It is a development of John Winthrop’s famous line, “We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.” (For those who don’t know, the city upon the hill that Winthrop was referring to is Jerusalem.) The concept that it engendered was that the American people had an indelible right to expand out and spread their democratic ideals to the world. And it is fairly reminiscent of the concepts expressed in Herzl’s Der Judenstaat. The Benjamin signs appear like physical manifestations of that idealized expansionism.

While the Benjamin sign literally reads “Welcome,” the message it is subliminally (and legally) revealing is the same as that on the Me’a She’arim sign. However, though they might be proclaiming a similar message, there is a significant difference between the two: intention. There is a fine line between depending on tradition to sustain a group identity and building on tradition to sustain a nationalistic intention. The line here seems to be the intention behind that use.

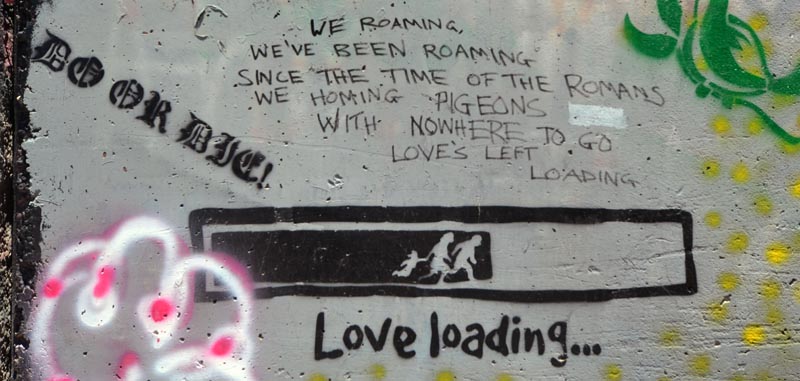

Figure 7: Graffiti on Israeli West Bank Barrier in Bethlehem

The Art of War

Let’s ask a simple question: What can art do? Let’s get more specific: What can art do with regards to displacement? Let’s be a bit more demanding, now: What can the representation of trauma in art do to alleviate the actual trauma of displacement?

Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel is a structure built along the Israeli West Bank Barrier in Bethlehem. Conceived as a temporary art installation now nearing the end of its third year, the building is a hotel, museum, café, and shop. It faces a segment of the barrier that is covered with graffiti voicing reactions to the current situation between Israel and Palestine. It is a blunt piece of political art, a commentary on the Jewish occupation of Palestinian land, on the illegal construction of the wall, and on the expulsion of Palestinians from their land. As all art with a political agenda, it has come under the scrutiny from all sides. Whether useless or effective, whether exploitive or critical, what can be said is that Banksy’s project is an architecture that talks about displacement. It is a building that turns the wall into a tourist attraction. And it does one of the few things art can do for a crisis: it popularizes it. And, as it does so, it also tries to turn the table on the way we respond to a piece of infrastructure meant to divide and weaken a group of people.

Figure 8: Graffiti on Israeli West Bank Barrier in Bethlehem

Banksy’s project may be normalizing a terrifying situation or using pain for the sake of art. Its injection of foreign humor into a very real human struggle may in fact be problematic on many levels. But one thing that it does with honesty is tell a story, and the story is this: with every wall that is built, there will be someone who will fight to tear it down. The Walled Off Hotel speaks to a culture that erupts in reaction to the construction of a structure such as the Israeli West Bank Barrier. That reaction is, obviously, dissent.

Dissent grows organically against oppression and injustice. Socially, that dissent can take the multitude of forms we know so well: boycotts, strikes, marches, terrorism, and war. Architecturally, though, that dissent has much less opportunity to manifest itself, simply because, within our society, to build takes more power than to walk, to speak, or to destroy—though it need not take more courage or dedication. It is nearly impossible to build without power. So, the powerless do not build. Or do they?

Figure 9: Graffiti on Israeli West Bank Barrier in Bethlehem

In the Absence of Power

While doing this research, I came up against a persistent road block. I wanted to find the architecture of displaced people, to find any sign of power among the spatially powerless. If architecture is a manifestation of power, what is the architecture of the powerless? Or, if we’re being blunt, what is the power of the powerless? That is the question I was asking. And the response I received was as disheartening as it was illuminating: Do not glorify the experience of displacement. Because any architecture built by displaced people is nothing other than the architecture of survival.

Refugees are especially aware of what it means to have the power over their surroundings stripped from them. They can be largely at the mercy of the host countries and aid groups that are responsible for them. Yet, as we’ve already seen, no two refugees have the same experience of exile; being displaced is not a singular indivisible experience. And to tell the stories of those little pockets of power within a seemingly powerless experience is not an act of glorification. It is just documenting a different perspective. This is one of the many stories within this grand multifaceted narrative that needs to be told.

Now, logically, the answer I’d received wasn’t considering displacement within the scope that it is looked at within these articles. It is an understanding of displacement that stops short of the moment in which the displaced begin to take back space. Within this frame, the architecture of displacement, much like the rest of the experience of displacement, is one of survival. But a state of survival isn’t always permanent. Displaced people can find their place again, be it by carving out new space or by reclaiming old space. Tectonic plates don’t shift only once. They have shifted many times and they will shift again. But don’t hold your breath. Because, like all things, it’s going to take a bit of time—and a whole lot of therapy.

Figure 10: Flower shop near Israeli West Bank Barrier, Bethlehem

1 Barakat, R. (2013). “The Right to Wait: Exile, Home and Return.” In P. Johnson (Ed.), R. Shehadeh (Ed.), Seeking Palestine: New Palestinian Writing on Exile and Home. (pp. 135–147). Northampton, Massachusetts: Olive Branch.

2 Abu-Lughod, L. (2013). “Pushing at the Door: My father’s Political Education, and Mine.” In P. Johnson (Ed.), R. Shehadeh (Ed.), Seeking Palestine: New Palestinian Writing on Exile and Home. (pp. 43–61). Northampton, Massachusetts: Olive Branch.

3 Avidan, L. (2019). “Shooting on the Green Line.” Lihee Avidan Photography. Retrieved from http://www.liheeavidan.com/shooting-on-the-green-line.

4 Auerbach, S. (2017, July 08). “No One Actually Knows Where Israel Ends and the Palestinian Territories Begin.” Haaretz. Retrieved from https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-no-one-knows-where-israel-ends-and-the-palestinian-territories-begin-1.5491999

5 Peters, F. (1985). Jerusalem: The Holy City in the Eyes of Chroniclers, Visitors, Pilgrims and Prophets from the Days of Abraham to the Beginnings of Modern Times. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University.

6 Volkan D. V. (2007). “Chosen Trauma, The Political Ideology Of Entitlement And Violence.” Retrieved from http://vamikvolkan.com/Chosen-Trauma,-the-Political-Ideology-of-Entitlement-and-Violence.php.

7 Herzl, T. (1989). The Jewish State. Mineola, New York: Dover.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top