-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Invention of Labor: British Industrial Architecture and Representations of the Working Class

Sarah Rovang is the 2017 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

By this late point in the fellowship year, I have the underground mine tour drill down pat: surrender your electronics, don a hard hat, attach the headlamp, get the safety briefing. What made my descent for the tour at the National Coal Mining Museum of England (NCM) unique, however, was the number of horrified gasps and decidedly British “tsk tsks” emitted by my fellow mine tourists once we started learning about this history and development of coal mining in Great Britain. Granted, this effusion of revulsion and disbelief was probably not abnormal, given the content of our tour (and I myself might be guilty of issuing one of the aforementioned gasps).

The Caphouse Colliery site where the NCM is located was first exploited for coal at some point during the early 1800s, and remained operational until 1985. The majority of the extant architectural features at the site date to the mid-twentieth century, and many of the surface-level exhibits attest to what life was like as a miner during this period. Given the scarce pictorial and architectural evidence for what working class life was like during the pre-photographic, early Victorian period at coal mines like this one, it is quite remarkable the lengths to which the National Coal Mining Museum has gone to resuscitate and document this shadowy period in labor history.

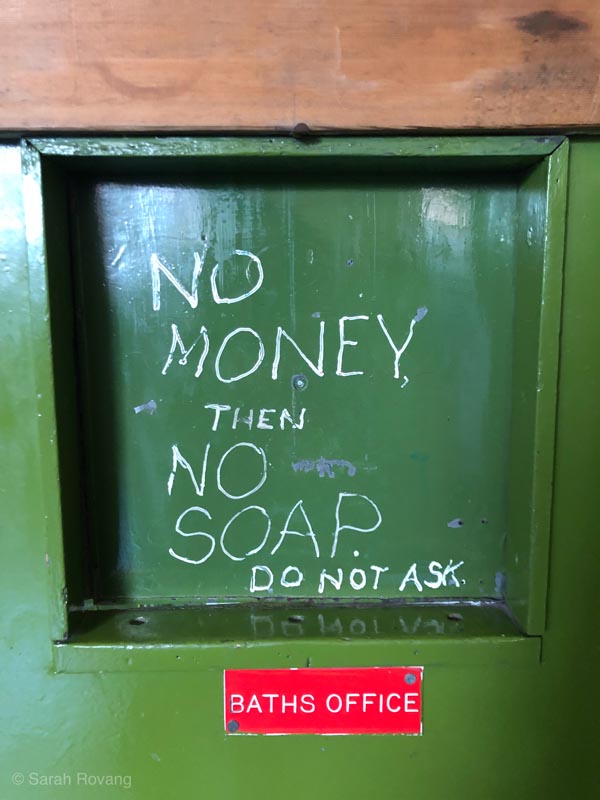

Scenes from the National Coal Mining Museum for England. The three top pictures show structures dating to the mid-twentieth century, including the headgear above the shaft where the underground tour is conducted, the miners’ locker room, and the door of the baths office. Below, the oldest structure at the Hope Pit site at NCM: the Inman shaft (stone building on the left), which pumped water using a beam-pumping engine. There is little definite evidence about the Hope Pit’s early origins, though John Blenkinsop, a railway engineer, is thought to have laid it out in the 1820s.1

140 meters under the earth, our tour of the former Caphouse Colliery started chronologically in the 1840s. Our guide, a longtime former coal miner at this mine, led us through a series of underground exhibits. The first featured a low door, less than a meter high. Beyond that door, a narrow tunnel extended into the coal seam. We learned that in the early nineteenth century British coal miners worked as families, including women and children as young as five. The architecture of the mine itself was rudimentary and ventilation relied on a fire at the base of the main shaft (yes, it’s as terrifying as it sounds). Working days frequently stretched to 14 or 16 hours, and life expectancies were conversely short; averaging 32 at this particular mine. I realized, standing underground before this vivid tableau of early mining, that the majority of other mine tours I’ve experienced this year have focused almost exclusively on mine architecture and methods dating to after the rise of industrial mechanization and the first wave of worker health and safety laws. Suffice it to say, I truly had no idea how brutish life was in the early days of coal mining.

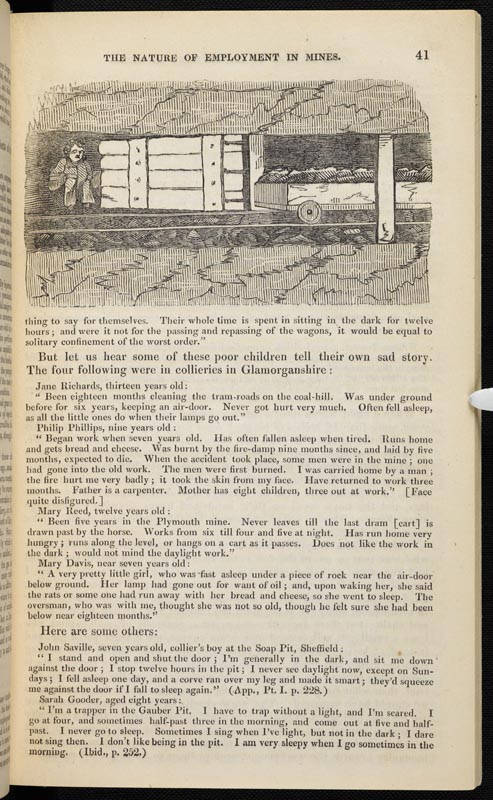

The idea of labor before the Industrial Revolution exists as something of a public history blind spot, in part becase documentation of working conditions is sparse. In the case of early Victorian mining practices, it is largely thanks to a unique illustrated textual source, the Royal Commission report of 1842 that the abysmal conditions of England’s coal mines are recorded in detail. At the NCM, one exhibition hall, entitled the “1842 Gallery” uses the report of the Royal Commission along with dioramas, audio installations, and archival material to reconstruct what life was like for early miners.

A page from the Royal Commission’s report of 1842, showing a child operating one of the underground “trap” doors that ensured fresh air was reaching the subterranean passages of the coal mine. Children like the one shown here frequently worked in complete darkness. Image source: “The Condition and Treatment of the Children employed in the Mines and Colliers of the United Kingdom Carefully compiled from the appendix to the first report of the Commissioners With copious extracts from the evidence, and illustrative engravings,” Parliamentary document, 1842, pg. 42, accessed June 29, 2019, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/report-on-child-labour-1842.

A life-sized exhibit at the 1842 Gallery, showing a mother struggling to keep her daughter from falling down an open shaft. Before the Parliamentary report mentioned above, coal mining families worked with virtually no occupational safety regulations. Accidents and fatalities were frequent.

As moving and well-done as the 1842 Gallery was, it lacked the visceral terror of being deep underground in a narrow coal corridor at that moment when our guide had us turn all our headlamps off to see what “real dark” was like—the only sounds were the shuffling of feet and the distant whir of the modern ventilation system in the inkiest, dimmest dark my modern, light-loving eyes have ever experienced. Our guide prompted us to imagine an entire working life spent in what the 1842 report called “horrible subterranean works,” mining coal in this all-consuming darkness, or by the light of a single candle.2

Examples like the 1842 Gallery point to the importance of using other kinds of evidence (in this case, textual and illustrative) alongside architectural material in telling the history of early industrial labor. In addition to this permanent exhibition, the NCM has just debuted a new display entitled “Mining Lives,” dedicated to telling the stories of coal miners and their families—an ambitious and comprehensive production that touched on the role of music, sports, print publications, art, and more in the lives of northern England’s mining communities, spotlighting especially the role of women and immigrant workers.

An image from the Mining Lives exhibition at the NCM showing a partial recreation of the exterior yard of a miner’s home.

Over the last month as I’ve explored post-industrial northern England and London, I’ve grappled with the ways in which the ideas of the “working class” and “labor” are not inherent social facts, but instead constructions that coincide largely with the advent of industrialization. The dissemination, adoption, and widespread normalization of these concepts can be attributed to a number of factors, including the rise of photography, which had the power to capture and transmit images of worker life outside of industrialized areas. Early photography was not particularly well suited to the hectic, dirty atmosphere of industrial sites. Exposure times were long enough so that while industrial architecture and machinery might develop looking crisp and composed, the faces and bodies of workers were nearly always blurred—unidentifiable and illegible.3

After photographic methods were improved, the widespread conception of the working class was accelerated by the advent of photography. As Ian Beesley, curator of the “Grafters: Industrial Society in Image and Word” exhibition currently on display at the NCM suggests, “Photography is an industrial process born out of the Industrial Revolution.”4 As photographic technology improved, documentarians like Jacob Riis and his contemporaries deployed photography to reveal the inequities of working class life and foment the movement towards housing reform, all the while furthering (whether consciously or not) the idea that something called a “working class” existed in the first place.

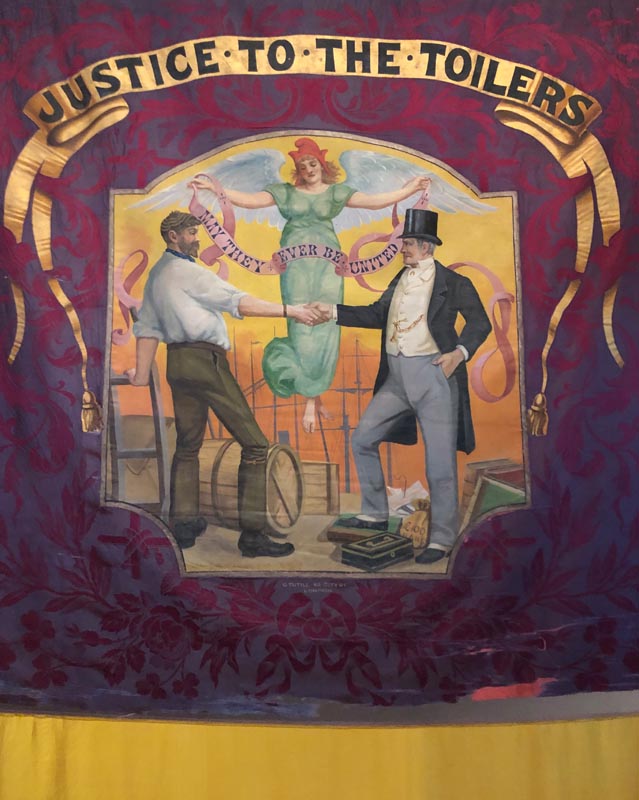

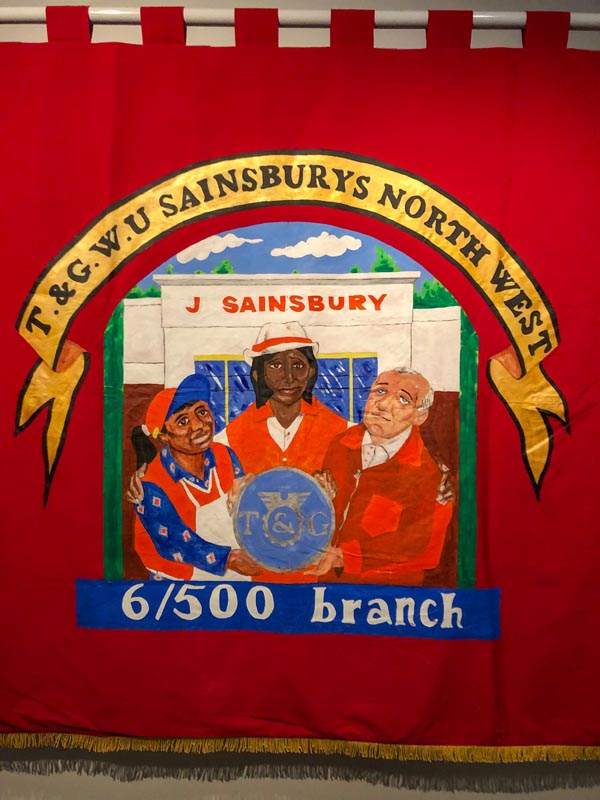

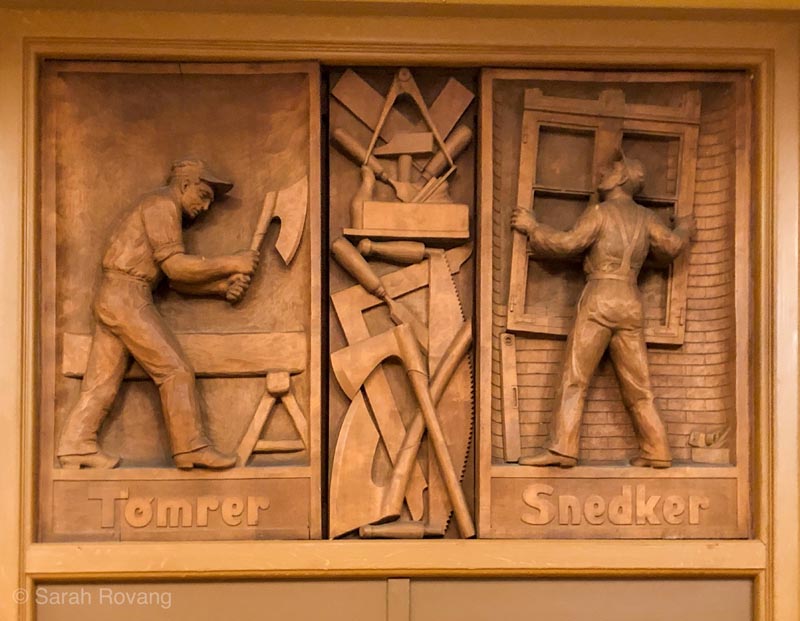

In addition to photography, and the occasional parliamentary report on working conditions, writers of both social theory (notably Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels) and realistic contemporary fiction (Charles Dickens, e.g.) helped crystallize a shared conception in Britain of a working class. Alongside mass media and the written word, the rise of unions and collective bargaining in the nineteenth century indisputably increased the political and social cachet of labor. To self-identify as a “worker” became critical to the idea of unionization, and relied on members’ solidarity to a common, class-based set of goals and values. Continuing a longer artistic tradition of trade-based iconography (dating all the way back to the days of guilds), nineteenth- and twentieth-century workers associations developed their own visual language, displayed on union banners, or carved into the reliefs that sometimes adorned the walls of union halls.

A banner created by the Ipswich Dockers Union in the wake of the Great Dock Strike of 1889; just one of many union banners that hangs in the People’s History Museum in Manchester, England. Emblazoned with the epigraphs “Justice to the Toilers” and “May they ever be united,” the massive banner shows on one side the image an employer and a worker shaking hands against a background of dark violet Jacquard silk. On the other, two dock workers are depicted surrounded by animal emblems of the British empire (a beaver for Canada, a kangaroo for Australia, an ostrich for South Africa, and an elephant for India).5

A more recent union banner, dating to the 1980s, which was carried by the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) in a 2005 protest as part of a larger pay dispute with Sainsbury’s supermarket chain. The TGWU started in 1922 and originally had about 96,000 members. Today it has around 1.2 million.6

Wooden relief showing the carpentry (left) and building trades (right) in the Festsalen, or Assembly Hall, at the Workers Museum in Copenhagen (constructed 1879).

In my SAH Blog post last month, I explored the relationship between visual representations of industrial architecture and the contemporary architectural designs and renovations of former industrial spaces that have tapped into or capitalized on those visual tropes. The images and artistic typologies I focused on in the previous blog were notably devoid of people, focused instead on the aesthetic, technological, and structural qualities of the industrial architecture itself. This month, I turn my attention to the social landscape of industry, and particularly to the ways in which public history construes the human geography of industrial heritage. In a recent post for the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Preservation Leadership Forum blog, I explored the ways in which the idea of “labor” might be manifested at an industrial heritage site, based on my observations of sites in South Africa, Japan, and Chile. I concluded that for the vast majority of industrial heritage sites, the choice to engage the realities of working class lives was a conscious act of curatorial re-insertion. Within the context of Northern British industrial sites (and a few in Scandinavia), I want to expand on that conversation, putting visual representation in dialog with architectural places to question whose stories are being told in what kinds of public history settings. In other words, how do architecture, artistic representations, and textual evidence come together in these public history settings to revivify the experiences of working people and help contemporary visitors to connect with their stories?

Anonymous Workers, Singular Owners, Paternalist Architecture

In Gallery Two at the West Mill in the UNESCO-listed company town of Saltaire, England, hangs a series of artworks by the muralist Henry Marvell Carr (1894-1970). A portrait painter and war artist during WWI, Carr was commissioned in the late 1950s to execute a series of murals for the still functioning wool mill originally founded by Sir Titus Salt in 1853.7 Though the murals are no longer intact, portions of them have been salvaged and are now displayed alongside memorabilia and artifacts from the long history of Saltaire. Highlighting the many stages necessary for turning raw Alpaca wool into consumer-ready cloth, the salvaged portions of Carr’s murals divorce their subjects (workers, machines, and the cloth itself) from any legible spatial logic. Instead, these subjects are suspended against flat planes of color or with minimal suggestion of the surrounding space and perspective. The effect of these mural portions is of surreal, de Chirico-esque windows into the alienation of the mid-twentieth century British working class. Even though Carr’s mural remnants are just partial survivors of a larger work, they reflect a common visual convention within art depicting the working class—namely that it is frequently about the type rather than the individual. Carr’s burlers, menders, dyers, and weavers have the same blankness of the disaffected American office-dwellers Edward Hopper was painting around the same time—their mute faces and turned heads deny us any access to their psyches.

Segments from the Salts Mill Mural by Henry Marvell Carr (1894-1970) showing stages in the Alpaca wool-making process.

Although Carr’s figures are more relatable than heroic, in their anonymity they can be profitably compared to the broader genre of worker memorials. After 11 months of travel, I have quite a photographic collection of worker’s memorials from around the world, and the vast majority of these depict an ideal, anonymous worker—typically male, often well-muscled, frequently of European extraction (even outside of Europe). He might be depicted engaged in work, or holding the tools of his trade like classical attributes. Every now and again, a worker monument might be modeled after a real person—a famous union agitator, perhaps. But overall, the worker, at least in art, is an Everyman. Solidarity may be comprised of individuals, but it is based in the notion of equality. The worker in the monument is every worker and any worker simultaneously.

Some typical and atypical examples of workers’ monuments all over the world, including (from the top), South Africa, Chile, Germany, Sweden, and Norway. The Swedish monument by artist Peter Linde depicts proletarian writer Moa Martinson, and stands near the textile factory where her mother work in Norrköping.

The interchangeability of the worker contrasts strongly with the singularity of the factory owner, particularly in the case of the numerous English philanthropic paternalists who planned and built their own company towns. Maybe it’s something to do the typically British fascination with eccentricity when it comes to architecture (see Sir John Soane), but still today, many of England’s utopian model towns remain cults of personality. At Saltaire, of course, there’s Titus Salt and his Alpaca wool empire. The architecture is delicate and Italianate despite the tremendous scale of the industrial buildings. Purportedly, when architects Lockwood & Mawson submitted their initial proposal for the first mill complex, Salt rejected it, noting that it was was “not half large enough.”8 Port Sunlight has William Lever, a soap tycoon with capacious architectural tastes and unsurprisingly strong feelings about clean living. And Cromford Mills, arguably the birthplace of the factory system, has Richard Arkwright, a bilious wigmaker turned entrepreneur of great cunning and paranoia. These figures each loom large at their respective heritage sites, often obfuscating or dwarfing any attempts to make labor a bigger part of the picture.

Cromford’s Richard Arkwright (1732-1792) was a pragmatist, his initial architectural aspirations inspired less by stylistic coherence than by profit margins. The pioneer of the water-powered spinning frame (also known as the water frame), Arkwright found the ideal confluence of geographic seclusion, reliable running water (the warm runoff of a lead mine), and available labor in Derbyshire, near the Derwent River. The highly polished masonry finishes on the original 1771-73 Cromford Mill building were not the result of high-minded ideas about making a nice environment for workers. No, Arkwright had merely salvaged the stones from a nearby manor house. Lacking the architectural finesse and geometric rigor of his successors, the original mill reads as a kind of insulated citadel—Arkwright feared the wrath of the machine-breakers who had sabotaged other attempts at early mechanized spinning elsewhere in England. Arkwright’s second, and more architecturally ornate, brick mill complex at Masson Mills (1783) just up the road, presages the showpiece factory type that would later become widespread across northern England, and eventually throughout Europe.

On a brilliant morning in May, I hiked the High Tor path from the town of Matlock at the northern end of the Derwent Valley to Cromford, which lies a few miles to the south. In the heart of Derbyshire, the Derwent River became the site of many early industrial experiments in cotton spinning. Far from other urban centers of northern England, where artisan spinners and textile workers had been known to sabotage spinning machines out of fear of losing work to mechanization, the Derwent Valley was difficult to access over land, and offered geographic protection from labor unrest. Moving goods and people in and out of the valley proved tricky and in a pre-canal, pre-railroad era relied predominantly on packhorses.

Above, the site of Arkwright’s second mill (1776), which was seven stories high and 120 feet long. The building burned down in 1890 but the remnants of the water-power system remain. One of the most powerful water wheels of its day, this wheel would have yielded between 20-25 horsepower.9 Below, the warehouse and the first mill building (1771).

Masson Mills, Arkwright’s showpiece factory is just a few minutes up the road. Above: One of the twentieth-century additions to the Mill in Accrington brick. Below: The 1783 mill building, which features notably more architectural detailing than the original Arkwright mills at Cromford.

Today, Cromford Mills has been largely redeveloped for retail and office space. A docent I spoke with reported that the bulk of architecture students who visit now are there to see how the site has been adaptively reused, rather than its original architectural features. The flagship interpretive apparatus of the visitor center is currently the “Arkwright Experience,” an immersive digital show that takes place in the original mill building. In this darkened space, Arkwright alights as a ghostly presence, bouncing like a digital phantom from one wall to another. Arkwright (or rather, the actor very convincingly playing him) gives an account of his entrepreneurial exploits against a backdrop that combines the real architectural fabric of the original mill building and layered, illusionistic digital projection.

Interior of the original 1771 mill where the “Arkwright Experience” takes place. The projection fills this end of the mill, demonstrating what the original mill would have looked like when it was filled with Arkwright’s cotton spinning water frames.

Perhaps the most compelling part of the “Arkwright Experience” was the way in which this projection, which encompassed one entire side of the building, was able to visually reconstruct at scale how the mill would have looked on the interior during its life as a cotton mill from the late eighteenth through mid-nineteenth century.10 Presented as a three-dimensional section cut-through, the projection showed how the factory would have been set up and the scale of the Arkwright water frames. I’ve participated in myriad “digital experiences” over the past year, and this was the one that most convincingly harnessed the historical architecture of the space as part of the public history interpretation. However, I found it telling that although the “Arkwright Experience” addressed issues of labor, and particularly the presence of child workers at the mills, the whole presentation (as the name would imply) was based around the voice, opinions, and story of Richard Arkwright.

At Saltaire, Titus Salt (1803-1876) occupies a similarly vaunted role within the site’s interpretive imaginary. Salt made his fortune through the innovative use of Alpaca wool in clothing textiles. Influenced by the writings of humanitarian Benjamin Disraeli, Salt believed that the lives and mores of workers might be improved through exposure to a more erudite architectural environment and more salubrious natural surroundings. The mill at Salt’s planned factory town of Saltaire opened in 1853. The statue of Titus Salt in Saltaire Park, with its rather whimsical alpaca reliefs, lords over the rest of the town, a geometrically-arrayed master plan of worker housing and numerous public amenities, including a bath house, almshouses, a dining hall, several schools, a church, a chapel, and allotment gardens. Saltaire is still occupied, though many of its public buildings have shifted in function—today several of the buildings in the town center are sub-let to Shipley College. Salt’s vision for the town dominates the Saltaire History Exhibition in the West Mill Building, and the many intact structures stand as testament to Salt’s extensive and sweeping town plan. Only a few obvious architectural changes, such as the demolished bathhouse and the modernized railway station, suggest that times and social needs have changed. The brightly painted doors and voluminous flower gardens testify to the individual tastes of the current residents, free (within the bounds of preservation restrictions) to personalize their dwellings.

Above: the Titus Salt statue in Saltaire Park, built 1903 to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of Saltaire Mills. Middle: the West Mill Building at Salts Mill (1851-53), where the wool spinning took place. Below: the Saltaire Institute (1867-1871; architects Lockwood & Mawson), now a community venue and part of Shipley College.

Scenes from the housing sector of Saltaire. The image below shows the site of the former Saltaire baths and wash houses, some of the few demolished buildings.

Port Sunlight, founded 1888, is likewise still inhabited, and today remains a major outpost of the Unilever corporation. At the Port Sunlight Museum, located in the former Girl’s Club, it is William Lever (1851-1925) who is the undisputed focus of the story, along with the architects he hired to execute his dream of a Garden City factory town outside Liverpool. In addition to a Lever-centric movie that plays on repeat, the museum itself is largely devoted to Lever’s biography, and the architecture and planning of the site. Following the self-guided walking tour map on sale at the museum, I wound my way past all of the architectural monuments that manifest Lever’s moralistic plan for harmonious worker living. Amidst the Garden City superblocks and rambling greenspaces are scattered many of the same offerings as Saltaire—church, school, garden allotments, etc. Unlike the grid of Saltaire, Port Sunlight follows the fashionable organic planning methodology of the late nineteenth-century, punctuated with radial avenues and a few more formal, symmetrically planned parks. Most notable is the Diamond, the long, axial park that terminates in the neoclassical Lady Lever Art Gallery.

Above: The Diamond, a long, axial park that terminates in the Lady Lever Art Gallery. Middle two images show two examples of Port Sunlight Housing. Although the worker cottages at first appear stylistically diverse, they are all based on vernacular traditions of Lancashire. Below, the former Girl’s Club, which today houses the Port Sunlight Museum. Both the Diamond and the Girl’s Club were designed by James Lomax-Simpson in 1912-13.

However, at the house next to the Port Sunlight Museum, now known simply as No. 22, a more individualized and personal vision of worker life in Port Sunlight starts to emerge. One the many Port Sunlight cottages designed by architect James Lomax-Simpson, this 1913 Edwardian worker’s house has been restored to show how the residence functioned as the dwelling of the Carr family for many decades, starting in 1913. The furnishings, architecture, and interpretive signs tell the story of the Carr family over time, including through the lens of important events like the royal visit of King George V in 1914 and the bombing of the Lever Brothers Soap Factory in WWII. Exploring this restored cottage helped me understand how Lever’s plan for worker housing played out on the small scale—how the values of cleanliness, hygiene, and privacy were made manifest in the three separate upstairs bedrooms, light-filled living room, and immaculate scullery. But it also gave a sense of how this ideal vision might be altered through the act of occupation by an individual working family, bringing their own tastes, history, and material possessions.

Above, the exterior of No. 22 next to the Port Sunlight Museum. Below, three interiors showing scullery, the parlor, and the master bedroom. Print publications specifically for residents of Port Sunlight “regularly reminded readers that Sunlight Soap should be used for clothes and Lifebuoy for cleaning the floors.”11 No. 22 was designed by architect James Lomax-Simpson, the godson of William Lever. Lever made him chief of the Lever Brothers’ Architectural Department in 1910.

Can sites like Cromford, Port Sunlight, and Saltaire be faulted for placing the emphasis of their interpretation on the intentions of their founders? In part, this choice is understandable because the majority of textual and architectural evidence at these sites serves to manifest the intentions of the owners. Indeed, I’ve observed a notable tendency to conflate the identity of these philanthropic paternalists and the architecture of their factory towns. Architectural identity becomes synonymous with personality and biography—a seductive narrative but one that is worth complicating. How do we then start to destabilize that mythology of the all-powerful founder/planner and anonymous, interchangeable worker? No. 22 at Port Sunlight suggests one way to approach this history—by focusing on an individual family and using architectural interpretation and reconstruction to revive the patterns, places, and experiences of their lives.

Resurrecting Vernacular Landscapes & Housing of the Working Class

”There might be toilers and moilers there in London, but she never saw them; the very servants lived in an underground world of their own, of which she knew neither the hopes nor the fears; they only seemed to start into existence when some want or whim of their master or mistress needed them.” (Elizabeth Gaskell, North & South, pg. 283)

The scullery in the basement of the Charles Dickens Museum in London. The Dickens family lived in this residence at 48 Doughty St. from 1837 until 1839. Typical of Georgian terraced homes of this period, the scullery and kitchen were relegated to the basement.

When Margaret Hale, the heroine of Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1855 novel North & South, moves with her family to a manufacturing town north of London, she becomes suddenly cognizant of the existence of the “working class.” While the architectural arrangement of her aunt’s house in London conspired to keep the servants separate from their masters, the urban condition of Milton, with its “long, straight, hopeless streets of regularly-built houses” punctuated “here and there” by “a great oblong many-windowed factory,” became a stage upon which the daily lives and rituals of the mill workers are rapidly revealed to the novel’s sheltered, middle-class protagonist.12 Margaret’s nascent consciousness of the working class comes with being in a new social and architectural environment. But for the readers of nineteenth-century novels living away from industrial areas, awareness of industrial working class life and its conditions came from the work of writers like Gaskell, a contemporary of Charles Dickens and fellow keen observer of Britain’s industrial social landscape.

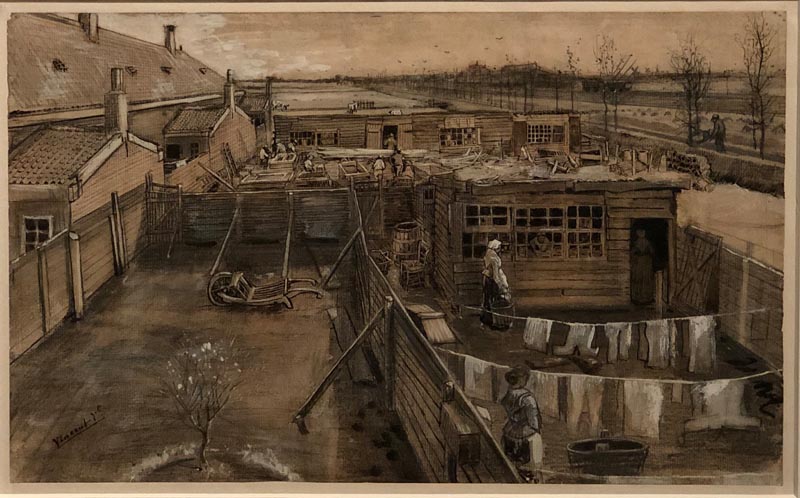

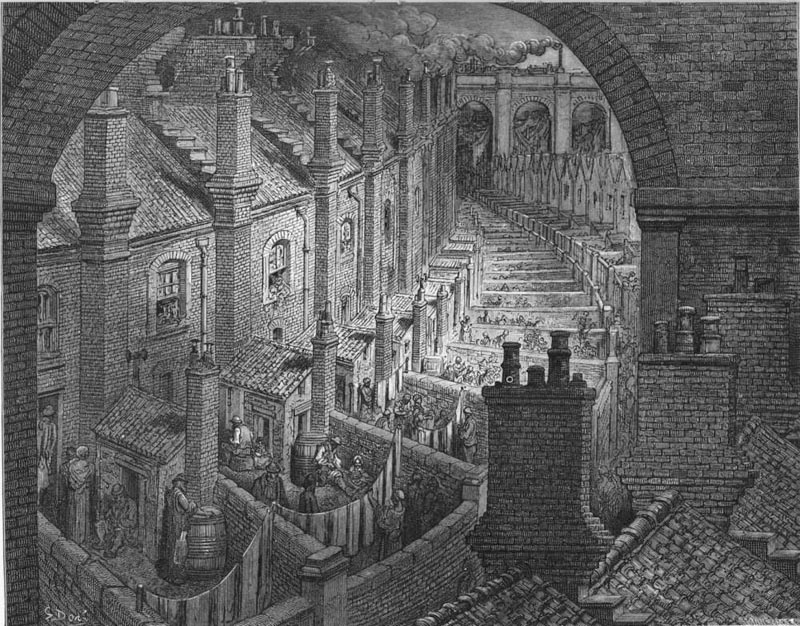

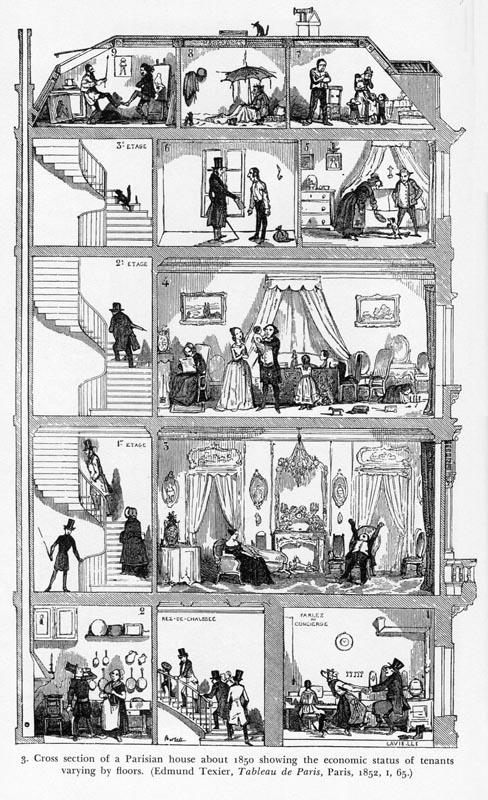

Alongside novels, nineteenth-century visual art also registers an increasing recognition of and indeed, fascination with, the “underground world” of the working class. In 1882, Vincent Van Gogh’s uncle commissioned the budding artist to create a cityscape. The resulting work, currently on display at the “Van Gogh and Britain” exhibition at the Tate Britain in London, depicts the yard of a carpenter’s workshop and a train depot in The Hague. The perspective of the work sets the viewer slightly above the action: not a full aerial view, but a slightly elevated vantage point that reveals the everyday activities of this quotidian scene. In the foreground, two women hang laundry in one yard, while in the adjacent court rests a lone plow. To the rear, human activity animates the busy carpenter’s shop. This liminal space of everyday work is framed on one side by the slightly more formal and symmetrical lines of the train depot, and on the other by sprawling fields. The exhibition at the Tate cites Gustav Doré’s 1872 engraving “Over London-by Rail” as a key influence for the work, and indeed the strange perspective and focus on the back yards of working class homes do create a compelling parallel. Both images also recalled to me Edmund Texier’s famous section-cut cartoon of a Parisian apartment building circa 1850, which shows the economic and social divisions by floors. Van Gogh’s tilted perspective focuses exclusively on the working class, and takes as its subject a semi-rural setting rather than an urban one, but shares an impulse to document and understand the lives of the working class. The images of Texier, Doré, Van Gogh, and other socially-minded artists of this period all strive to make known the spaces that for much of society, might go largely unknown or unseen—bringing the places of “moilers and toilers” out into the light.

Vincent Van Gogh, Carpenter’s Yard and Laundry, The Hague, late May 1882, graphite, chalk, ink, and watercolor on paper.

Gustav Doré (1832-1883), Over London-by Rail, engraving, London, England, 1872, Illustration for Douglas Jerrold's London, facing p. 120. Source: Victorian Web, accessed June 30, 2019, http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/dore/london/30.html.

Edmund Texier, Tableau de Paris, Paris, 1852, I, 65, “Cross section of a Parisian house about 1850 showing the economic status of tenants varying by floors.” Source: Pinterest user aubreylstallard, accessed June 30, 2019, https://images.app.goo.gl/5kjKCiaWAD6FaWEm8.

These kinds of vernacular working-class places with their temporary structures and makeshift workspaces carved out in alleys or sandwiched between larger buildings, are typically not architectural history’s survivors, nor are they typically what attract our attention as tourists. Dazzled by copious spring blooms and the symmetrical forms of company worker housing, I nearly missed the Old Nail Shop on Joseph Street in Belper, England, where I had gone to explore Strutt’s North Mill. Jedediah Strutt rebuilt this Derwent Valley mill in 1804, and it remains the second-oldest surviving cast iron frame building in the world. Before Strutt brought cotton spinning to Belper, the town’s primary economic activity was nail making, a family trade that prior to mass production, was the kind of painstaking skilled craft that happened in makeshift production spaces attached to homes; a kind of cottage industry.13 Once Strutt swooped in and built regularized worker housing, constructing the “Long Row” and “the Clusters,” the vernacular workshops of the nailers were largely lost. Still, as I wandered the neat, parallel streets of the mill workers’ housing, I nevertheless came upon a small stone building that was decidedly different than anything around it. Peering through the window, a small display of tools and the illustration of a nailer at work hinted at the cottage’s original purpose. I would later realize that the Old Nail Shop is indeed included on tourist maps of the Belper area, but in the moment it felt like a chance encounter—a built fragment of working life of Belper, dating to the days before Strutt amassed his fortune and gradually built up the neighborhood around it into regularized housing.

Above, the Old Nail Shop in Belper, England. Below, an illustration in the window showing a nailer at his craft.

Strutt’s North Mill, which was reconstructed using a cast iron frame in 1804. In the background (brighter red brick building) is the East Mill, which dates to 1912.

Worker housing built by the Strutt family between 1790 and 1850. Above, the “Long Row,” row houses with small front porches and a common yard. Below, the “Clusters,” groups of four houses in one structure meant for higher ranking mill workers, each with their own private garden.

From the perspective of public history, there was something particular and visceral that came from discovering the nailer’s shop—something more just hearing about the Belper nailers back in the Strutt’s North Mill interpretive center (although it was because I was armed with that information that I could figure out what I was looking at). In my experience over the past year, it has been through these kinds of places that I am better able to empathize with the past by imagining myself not just in an abstract economic or social situation, but in a specific (and thus, meaningful) built place. It’s in that moment, when all the lights go off in the mine, or I unintentionally stumble across something unique and precious like the Old Nail Shop, that working lives of the past feel the most real.

Because relatively few original examples of vernacular working class spaces survive worldwide, many institutions that I’ve encountered have turned to recreating these kinds of spaces within both larger open-air architecture exhibits and at indoor museums. Back in October 2018, I visited the Shitamachi Museum in Japan, which features the recreation of a two-family tenement house dating to the Taishō period (1912–1926), populated with period items donated by the public. By the time I visited this exhibition, I had been in Japan nearly two months, learning all the ways in which the economic and technological changes of the Meiji period transformed the sociocultural landscape of Japan. But the experience of standing in this cramped, working-class dwelling, allowed me to step into the proverbial shoes of the people who would have occupied residences like this, balancing tradition and modernity in their daily rituals and patterns.

More recently, I visited some excellent examples of recreated vernacular housing in Scandinavia, including the Workers Museum in Copenhagen and the Norse Folkemuseum in Oslo. At the former, the stage is set in the very entrance to the museum, where laundry on the line welcomes visitors to a recreation of a 1950s workers’ flat belonging to the Hansen family. The story of this specific family told through the exhibit also evidences the wider changes of Danish life during the postwar period: the end of wartime austerity, the rise of consumer culture, and the increasing affordability of midcentury modern Danish design items. Another permanent exhibition shows a flat belonging to the Sørensen family in the 1915. Framed as snapshots of particular eras, these two exhibits when taken together show the dramatic changes in Danish working class life over the course of forty years. The Norse Folkemuseum (Norwegian Museum of Cultural History) features an even greater diversity in time and experience in its entirely reconstructed tenement house from Oslo (Holmens gate 5, originally built 1865). The tenement house has been reconstructed to show how many different residents occupied this same space over the years, and transformed the architecture and design of the tenement apartments according to fashion, class status, and cultural preference. The working- and middle-class residents featured in these displays include actual former inhabitants, who gave oral history testimony that went into the recreation of these spaces. Several apartments are also based more broadly on “types,” including one belonging to a single woman doctor from the 1930s, and a Pakistani family from 2002.

Above: the entrance to the Workers Museum in Copenhagen. Below, a recreation of a living room in a working-class 1950s Copenhagen apartment showing the end of wartime austerity and a newly affordable consumer culture.

Above: The exterior of the reconstructed Oslo tenement (1865), Holmens gate 5, that now resides in the Norse Folkemuseum. Center: The living room and sleeping area of Gunda Eriksen (1887-1959), a cleaning lady for an advertising agency who lived in this building for 20 years. Small apartments like this one did not have separate bedrooms and the couch seen here would have also been used for sleeping. Below: A construction of how a Pakistani immigrant family might have lived in Oslo around 2002. As the sign at the apartment explains, “the exhibition does not attempt to show how all Pakistanis in Norway life. Pakistani homes vary as much as Norwegian homes, according to the background, taste, and means of those living there. This is just one example.”14

In neither museum did the exhibits rely on costumed, historical re-enactors to revivify the spaces in question. Rather, the period objects, the restored architecture, and the movement of the visitor through these spaces activated them as lived environments. Just as Van Gogh’s image of the carpenter’s yard is an oblique, distant, and partial view, these recreations of vernacular working-class architecture are necessarily incomplete. Nevertheless, they provide a deeper and more bodily public history engagement between the visitor and the past. As the epigraph of the Oslo tenement building’s exhibition reminds us:

A house is petrified time

Amalgamating and transcending

The past and the future

In the inhabited space

Built in the past

And remade by generations

Following each other

An old townhouse

is a time machine

Opening doors

To different rooms

in the past15

Conclusion: Global Constellations of Labor

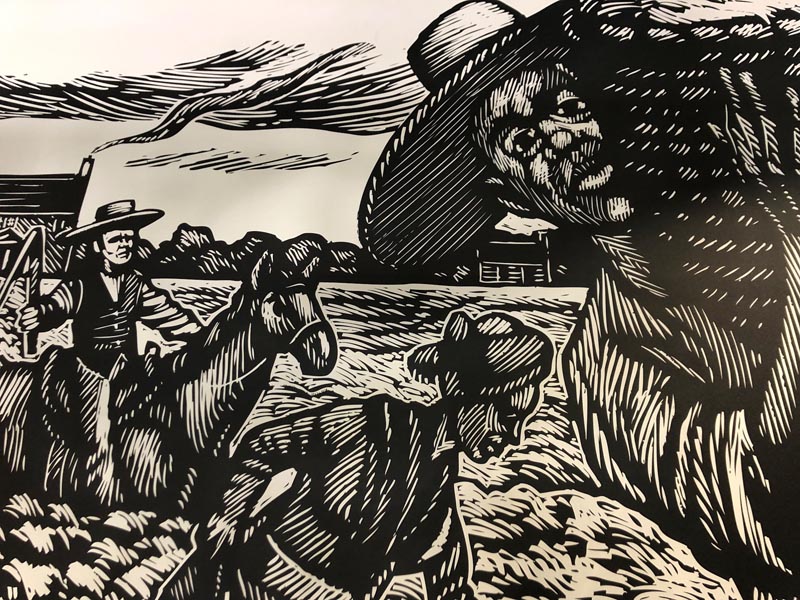

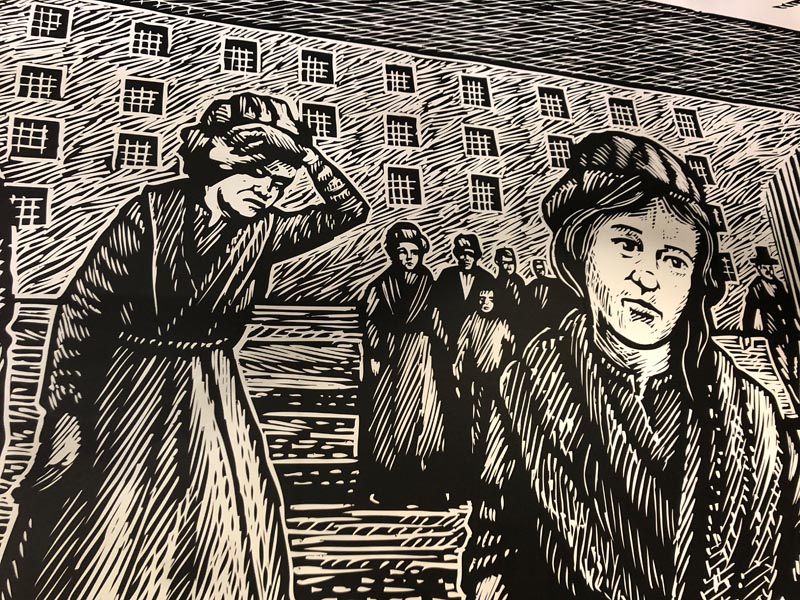

As public history institutions have broadened their ideas about what kind of topical material artifacts, text-based evidence, and architectural spaces should be included in storytelling about industrial workers, contemporary artistic representations have likewise become more globalized in their scope. Two pieces in particular from my time in the U.K. have stayed with me as possible indications of the next phase of imagining working class lives: Alke Schmidt’s The Work of Salts (2018), on display at Saltaire, and Brian Gallagher’s Global Cotton Workers Mural (2016) at Cromford Mills. Both of these artistic interpretations of working class life expand the idea of “labor” beyond British workers in textile mills to include a much wider range of people who participated—sometimes voluntarily, often not—in these industries around the world. Schmidt’s aggregative reinterpretation of Saltaire places the architectural edifice of Salt’s West Mill at its center, fronted by several Victorian bourgeois women, clad in Salt’s signature fine Alpaca wool. Around the periphery, a palimpsest of images and maps depict the other people and places who contributed to the manufacture of wool in Saltaire, including both South American Alpaca farmers and British factory workers. The painting is part of a larger series entitled Wonder and Dread that “explores the politics and morality of global textile supply chains and situates Bradford’s wool industry in an international context.”16 Gallagher’s mural in the Cromford UNESCO interpretive center likewise illustrates the range of other people and experiences that were embroiled within the global cotton trade, including enslaved African field workers in the Americas and the Indian weavers who lost work in the wake of industrialized spinning and weaving. While Schmidt’s painting is lush, illusionistic, and richly saturated, Gallagher used a scraperboard technique to produce a stark, graphic landscape of human labor that spans an entire wall within the visitor’s center.

Alke Schmidt, The Work of Salts, 2018, commission for Salts Mill, part of the series Wonder and Dread, oil and acrylic on cotton.

Portions of Brian Gallagher’s Global Cotton Workers Mural (2016, scraperboard), showing enslaved African workers on a North American cotton plantation, and textile works at Cromford Mills.

While Margaret Hale’s experience of the industrial working class in North & South was limited to her neighbors in Milton, the British cotton industry was already highly globalized, reliant on the work of enslaved African people in the Americas, and networks of trade and exploitation across the British empire. While that part of the story remained hidden from our 1850s heroine, it is increasingly becoming an essential part of how British and other European industrial sites treat the story of labor. Artistic imaginings like the ones described above suggest that the way forward is not to place the individual sites and experiences of working people across the globe on the same, even plane—to imagine an unreal, idealized solidarity between all workers everywhere. Instead, they embrace an intersectional reading of class, work, and capitalism that values individual experiences and the numerous other factors—race, gender, religion, and others—that colored the lives of industrial workers past.

- “Hope Pit Station,” onsite interpretive signage at the National Coal Mining Museum for England, photographed May 17, 2019. ↩︎

- “The Condition and Treatment of the Children employed in the Mines and Colliers of the United Kingdom Carefully compiled from the appendix to the first report of the Commissioners With copious extracts from the evidence, and illustrative engravings,” Parliamentary document, 1842, pg. C2, accessed June 29, 2019, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/report-on-child-labour-1842. ↩︎

- Ian Beesley, “Grafters: Industrial society in image and word,” wall text, National Coal Mining Museum for England, photographed May 17, 2019. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Ipswich Dockers Union banner, 1890s,” text label from the exhibition “The Past, Present + Future of Protest” at the People’s History Museum in Manchester, England, photographed May 18, 2019. ↩︎

- “T.&G.W.U Sainsbury’s North West Banner, 1980s,” onsite interpretive signage at the People’s History Museum, Manchester, England, photographed May 18, 2019. ↩︎

- “Henry Marvell Carr, RA (1894-1970, British Artist,” wall text at Salts Mill, photographed May 16, 2019. ↩︎

- “Salts Mill,” Saltaire Village World Heritage Site, accessed June 28, 2019, http://www.saltairevillage.info/Saltaire_WHS_Salts_Mill.html (information on this site is extracted from the World Heritage Committee Nomination Document, 2001). ↩︎

- “Cromford Mills: Inside the Second Mill,” onsite interpretive signage, Cromford Mills, photographed May 23, 2019. ↩︎

- “Key Sites - Cromford Mill,” Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site, accessed June 29, 2019, http://www.derwentvalleymills.org/derwent-valley-mills-history/derwent-valley-mills-key-sites/key-sites-cromford-mill/. ↩︎

- “The Scullery,” onsite interpretive signage, Port Sunlight, photographed May 20, 2019. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Gaskell, North & South, Kindle Edition, 42. ↩︎

- “Belper Nailers,” pamphlet of the Derwent Valley Visitor Centre, Strutt’s North Mill, Belper, accessed June 29, 2019, https://www.belpernorthmill.org.uk/downloads/Leaflet-2-Nailers.pdf. ↩︎

- “Pakistanis in Norway,” onsite signage, Norse Folkemuseum, Oslo, Norway, photographed June 10, 2019. ↩︎

- “Living in the City: Exhibition in the Apartment Building,” Norsk Folkemuseum, accessed June 29, 2019, https://norskfolkemuseum.no/en/living-in-the-city ↩︎

- The Work of Salts wall label, Salts Mill, Saltaire, England, photographed May 16, 2019. ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top