-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

On Beauty and the City: A Brooks Final Report

Zachary J. Violette is the 2018 recipient of the short-term H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise noted.

When I conceived of applying for the Brooks Fellowship back in the summer of 2018 I was in a period of intellectual expansiveness. I had just concluded what had been a decade-long research project—initially my dissertation, then my first book—on the American tenement. This was a small but crucial piece of my larger interest in the city writ large of the (long) nineteenth century, and its physical and visual manifestations. How did people, who suddenly found themselves in a new world of both abundance and unsettling change brought about by the new industrial order, mediate their experiences through architectural form? But last summer I was also feeling the limitations of my training and my intellectual horizons more generally. While trained as an Americanist, I never really conceived of my work in narrowly provincial, or even geographically constrained terms. Still, the wider urban world, even the wider western world, was largely an abstraction to me, understood mostly through reading and fairly limited travel. (When I wrote the Brooks application I had only been abroad twice, never alone, and never when I could focus solely on my work.)

My sense that I did not adequately understand the context of the things about which I spoke was heightened by an important realization that I came upon late in the process of researching the tenement book. Most of my subjects for that project had come from central and eastern Europe; many of them were even trained there. For all of them the cities of that region had acted as an important reference point for how the modern city looked and was arranged. This gave them, I understood, a view of the city and its buildings that was different than many Americans. It became increasingly clear that the buildings I was looking at, profuse with unusual forms, were something of a cultural hybrid. With a sense that my interests might be more transnational than I had realized, I sketched out a series of observations based on the resources available to me. I knew, in short, that there were buildings in Berlin and Vienna, in Vilnius and Kyiv, that bore significant relationships to those that I was interested in in New York and Boston. But this increasingly broad viewpoint ran headlong into a core methodological conviction that I held dear as a vernacularist: that you have to look at a lot of buildings, and their context, to really understand any of them. A few isolated and decontextualized examples are shaky ground on which to build an argument about the everyday landscapes in which I am interested. I felt a bit queasy about the assertions I was making about places I had not seen.

All that said, I also recognized, that the Brooks Fellowship was not intended to support a research project. And therein lay its great attraction. With the tenement book already off to the copy editor by the time I was writing my proposal, and with the current book in the works still American in its scope, my aspirations for the trip were more general. Indeed, at that point I had not really seen enough of these places to form any serious research questions about them. What I really needed to do was reconnaissance. I wanted to understand the broad contexts. I wanted to see and feel. To look at relationships between things. To observe and contemplate. This is exactly what the fellowship was designed for.

But in the spirit of only asking for what you need, my request was moderate: travel to ten cities over the course of 60 days, broken up into two legs, interrupted by conference season. This resulted in what I understand to be the first short-term Brooks Fellowship ever awarded. In the spring: Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest, and to not be entirely western-centric, Istanbul. In the summer: Warsaw and Lodz, Poland; Vilnius, Lithuania; and Lviv and Kyiv, Ukraine. To take advantage of more reasonable flights (the original plan had been for each leg to start in Berlin) the summer trip began briefly in Paris and ended in Rome. Those were two places not on the original itinerary, but never having seen the latter city before, it turned into an important detour. In retrospect I regret not being more ambitious, asking for a longer fellowship term with more generous stays in each city and more places on the itinerary. But the compressed nature of the trip allowed me to hone the skill of achieving a high-level understanding of the essence of a place, and accumulating a lot of data on it, quickly and efficiently. The first days in each city were usually a mad dash, covering as much ground, often to the point of exhaustion, as possible. These were the “fieldwork” days. I worked in concentric circles, starting in the old core of each city, and working my way out through the nineteenth-century extensions, and outward. My aim on these days was thoroughness, at least a thoroughly representative sampling of the sort of things I was interested in. If the early days were expansive, the middle days were intensive. This was the time to go into things: museums, churches, palaces, opera houses (so many of these), building lobbies and courtyards, anything that was open. The final days, which I always looked forward to, were the time for contemplation and reflection. Here I would go back to some of my favorite spots—parks and promenades, cafes, or most commonly the quiet interiors of baroque churches—and spend uninterrupted hours writing and sketching. Here is where I consolidated everything I saw and attempted to understand it.

I operated with two or three basic, guiding questions. First, I wanted to look at the diffusion, spread, and differing forms of the tenement and the bourgeois apartment building. I understood the fundamental difference between continental Europe and the United States was the extent to which the core of their cities was built up with multi-family housing. I also knew that the “rental palace” was a highly contested form in many of these places, fraught with meaning and association. I wanted to understand them in depth and in breath, to more fully comprehend their spatial and aesthetic logic. And most of these were set within cities that had grown substantially in this period, so understanding this context, and the relationship between historic core and nineteenth-century growth was a particular focus. The edges between older core and new extension, usually the site of former city walls, was a particularly fertile place for exploration. (Figure 1) In part this was because in this edge landscape was placed many of the apparatuses of bourgeois culture: opera houses, museums, universities and other institutes, government buildings of all sorts. And this usually related to some major shopping street, with a phantasmagoria of retail architecture. A second, related interest, in this landscape centered on architectural ornament. These places, in the nineteenth century, were the epicenter of the most florid forms of exterior decoration, on the widest range of building types, of perhaps any point in history, anywhere in the world. So long the subject of modernist opprobrium, I do not believe we yet understand the significance of this culture of ornamentation fully on its own terms. I wanted a fuller sense of what eclecticism and historicism—the two amorphous -isms of nineteenth century architecture—really meant, on the ground, for most people. And I sought to gain an understanding of the regional variations of ornamental forms within buildings that were, in general, programmatically consistent from city to city. (This is the germ of my next project—the third book.) Finally, the twentieth-century reaction to these buildings was also an unexpected source of fascination: the stripped facades of Berlin, their exclusion from the selective postwar reconstruction of Warsaw, the large-scale demolitions in Bucharest, their decay in Budapest and Lodz, the pristine restoration in Vienna. In all of these places the contrast between the hopefulness embodied in the nineteenth-century landscape, and the despair suggested by its devastation in the tragedies of the twentieth century, was powerfully resonant.

Figure 1. The edges between the historic core and nineteenth-century extensions proved to be a particularly fertile place for exploration. Here in Lviv, Ukraine.

Travel, of course, allows for a deeper understanding of a place. This is particularly true if you’re able to use a city the way it was intended. To this end, I planned as many aspects of this trip as possible to support my research interests. This was particularly true of accommodations. Instead of hotels, in every city I stayed in an Airbnb, most of which were located in exactly the sorts of buildings I was interested in. Not only were these located right where I needed to be, it meant I got to spend pretty much my entire trip living in the kind of “rental palaces” I was studying. Indeed, some of the most important insights from the trip came from the privileged and intimate access to courtyards, staircases, balconies, and interior spaces that these accommodations allowed. The last day in each city always involved careful recording of these spaces, including measured drawings. Through luck or intention, I was able to stay in some very interesting places. In Berlin, my front-facing flat, which retained all its plaster moldings, had a balcony with a view of one of the best-preserved tenement streets in the city. (Figure 2) In Warsaw, I stayed in one of only a handful of nineteenth-century apartment buildings to have survived the war and postwar redevelopment. In Lviv, my flat, in a building with incredible Secessionist moldings, was situated on a grand landscaped boulevard, closely reminiscent of the contemporary Vienna Ringstrasse. (Figure 3) The balcony had a fantastic view of the opera. In Lodz I stayed in a working-class tenement at the rear of one of the city’s unusual deep courtyards. And in Istanbul my flat was on the main floor of a nineteenth-century merchant’s house in Beyoğlu. It retained an incredible frescoed ceiling, elaborate plaster moldings, and wall painting throughout. (Figure 4) In many of the cities, “third places” also provided surroundings appropriately conducive to research and contemplation. In Vienna I became a regular at a wonderfully preserved turn-of-the-twentieth-century cafe near the Naschmarkt, where I spent many long evenings writing. In Prague, I was able to experience both an opera at the Czech National Theater (Figure 5) and Vivaldi recital at the Municipal House. Experiencing such buildings first hand in this way was really the best way to see them. And in Istanbul I was able to more fully comprehend the transcendent role of the dome in a Turkish bath, designed by the famous architect Sinan, on the last night of my spring trip.

Figure 2. View from my flat in Berlin.

Figure 3. View from my flat in Lviv, showing the city’s opera house and grand boulevard.

Figure 4. My flat in Istanbul retained incredible plaster moldings, fresco ceilings, and painted wall panels. It was located on the second floor of a 19th-century merchant’s house.

Figure 5. A building like the Czech National Theater is best experienced as a member of the audience of an excellent performance of Rusalka.

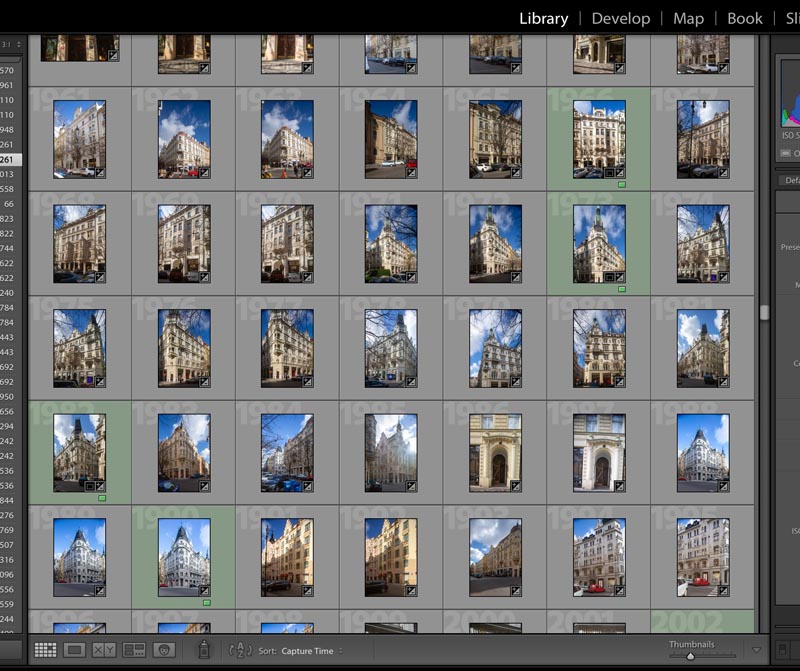

The extent to which the Brooks Fellowship was fabulously generative and productive for me can, in some ways, be easily quantified. Over the fellowship term, for example, I filled four full-size Moleskine notebooks with writing and sketches. On the more contemplative days entries stretched to 25 or more pages. Even more substantially, I shot 35,376 photographs over the course of the two months—an average of over 3,000 in each city. This, in particular, demonstrated my desire for extensive documentation: I sought to photograph everything, important landmarks and everyday places. (Figure 6) Of these, just over 400 of the best have recently been uploaded and published on SAHARA. In my initial contributions I have focused on places that had previously been under-represented in the database or missing entirely. Here I have tried to achieve a balance between famous sites, images of which would be useful to the widest audience, and the more representative buildings that have made up the majority of my photographs. I have selected many hundreds more images to share and I am in the process of cataloging these to publish on the platform in the coming months.

Figure 6. Sometimes, thorough documentation meant recording multiple views of every building on a street, as in this Lightroom screenshot showing thumbnails of my photos from Prague. Items highlighted in green have been selected for eventual inclusion in SAHARA.

Clearly, this brief but intense period of activity has set me in good stead. But the most important aspects of it are the least quantifiable, because they were the most transformative. Indeed, it does not seem like hyperbole to say this time has been career-shaping, perhaps even life-changing. The large visual archive I built is intended to provide teaching images that will serve me throughout my career. (In grad school I had thoroughly admired my professors’ dated slides, clearly taken on research trips when they were much younger and had long aspired to the same thing.) Additionally, I now have a stock of high-quality images, ready for publication in future projects. The trip has not only supported the global turn—to use the buzzy phrase—in my own work, it has taught me how to go about executing it. And my notebooks are now filled with so many insights, so many lines of inquiry, that it would take more than a lifetime to fully do these questions justice. My research agenda is now set well into the foreseeable future, and the third book is beginning to write itself before the second one is even finished. But these entries are more important than that. Many are deep meditations about the fundamentally human longing, the aching search for beauty. This was something I could feel viscerally, sometimes to the point of tears, throughout my travels. No picture, no slide, no insightful text can make you feel that way, can connect you to those spirits. These are the sorts of things that only the periods of intense concentration, provided by the Brooks Fellowship, have allowed me to begin to comprehend.

On the last day of my Brooks-funded travels, waiting for a late flight out of Rome, I spent all morning and a good part of the afternoon in the Pantheon. Writing. Drawing. Thinking. Staring out the oculus at the clouds and the sun. I had been drawn there like a magnet during my few days in the Eternal City. The place was at once familiar to me, seen so often in grainy slides. But the experience was wholly alien, and incredibly powerful. The evening before, after dinner, I had sat on the portico until late at night and watched a full moon rise between the columns. My musings, that night and the following day, were on the meaning of architectural history, and its great power in this world of darkness. The nature, the meaning, the purpose of our field became as bright and clear to me as the moon that night. It is our great privilege to dwell in the manifestations of the human soul at its best, that is, in its search for beauty in a complex and cold world. It is our job to bask in the reflections of the light of the past, and our awesome responsibility to protect this and project it into the future. I could not have imagined coming to such a fundamental insight when I began this journey. And it certainly would not have been possible without the Brooks Fellowship. For this I will be forever grateful.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top