-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Morocco's Streets of Many Ways

Aymar Mariño-Maza is the 2018 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Figure 1: Tanneries in Fes

Does anyone remember the grey area? Well, it’s coming back, like the winter cold your snotty-nosed nephew just gave you, which his snotty-nosed classmate gave him, and which he then gave his parents and his grandparents and, most importantly, you. You’ll give it to your colleagues at work and to your friends and to strangers at the bars, trains, lobbies, and elevators. The grey area is the kind of thing that spreads. But, much like that same cold, it doesn’t look the same everywhere you go. By the time you got your nephew’s cold, it was only really a headache but when you give it to that woman you chatted with on the sidewalk, it will keep her in bed cursing you for a week. Last time, we talked about the lack of adequate information that surrounds many historical experiences of displaced people. It was grey like the grey skies that hang low over the buildings across England. This time, we’ll see it in shades of gold leaf and Berber silver, cobalt blues and greens as tempting as paradise itself.

Morocco is an overstimulated area of overlapping histories, many of which get buried by the heavy weight of life itself or, as we’ll see later on, even get burned to the ground. We’ll trace her histories, reaching as far north as Andalusia, as high up as the Atlas Mountains, and as deep into the desert as the footsteps of the Tuareg people.

The Cross of Agadez

While doing what my generation does best (getting lost in the internet), I came upon a legend about the enigmatic Berber clan of the Tuareg. Now, let me be clear here: I have absolutely no faith in the credibility of the sources and for all I know this legend is either a hoax for tourists or the product of a highly imaginative Wikipedia writer. All the same, I will tell it to you because I’ve long since given up hope of trusting any source fully and because I just like the story. Just for good measure let me mention Roland Barthes, the French philosopher and semiotician, who wrote the following line, which I will take out of its context and appropriate here: in this study we are not “concerned with facts except inasmuch as they are endowed with significance.”1

The story tells of a legend that lives around the mythical “Cross of Agadez.” According to this legend, the cross is a traditional symbol passed down from father to son. The father handed the pendant to his son with the words, “I give you the four corners of the world, because one cannot know where one will die.” The sentiment is a beautiful one, even if it is just a myth. Barthes might remind us at this point that we would be hard pressed to find anything considered significant within our society that isn’t myth—but more on him in a bit. First, let me tell you a bit more about this strange and enigmatic cross.

Figure 2: Weaving loom in the attic of a Berber carpet shop

The Tuareg are one of the remaining nomadic tribes of the Sahara, inhabiting a notoriously inhospitable area in this already inhospitable region of the world. The legend of the cross expresses the significance of the symbol as an amulet, emblem, and heirloom. The Cross of Agadez, supposedly named after their city of Agadez, has a curious resemblance to an abstract representation of the cardinal directions. On a dirt path near the Kasbah in the Imlil Valley, a man described the cross as “the Berber map.” But word of mouth isn’t considered to be an altogether accurate source. Word of mouth, just like any other form of empirical evidence, just as ethnography on a whole, is a tricky source in historical studies. One thing that it does well, perhaps better than many other forms of evidence, is speak to the mythical elements of life.

The “true” origin of the symbol is shrouded in mystery while the symbol itself has been appropriated by mainstream markets. Travelers can find it all across Morocco, dangling from shopfront boards in the winding streets that surround Marrakesh’s Jemaa el-Fnaa, lain out on Berber blankets on the mountain paths crossing the High Atlas, and adorning trinkets, pottery, and any other object you might be searching for in one of the many markets across the country. The form of the symbol is the same, more or less, but its meaning has evolved.

As Barthes tells us in “Myth Today,” the last chapter in his seminal book Mythologies, that “myth is a type of speech.”2 What he means, and what he clarifies soon after, is that myths are things within our world that express meaning. Sure, a pendant is just a pendant, he would admit, but it is not just a pendant if used by a nomad to assure himself of his sense of place, to help him navigate not just the physical desert but the lack of home, structure, and safety that come with a nomadic life. And it isn’t just a pendant if a tourist believes the previous story, appropriates it within her own life, and then wears that pendant to help herself navigate her own inhospitable world.

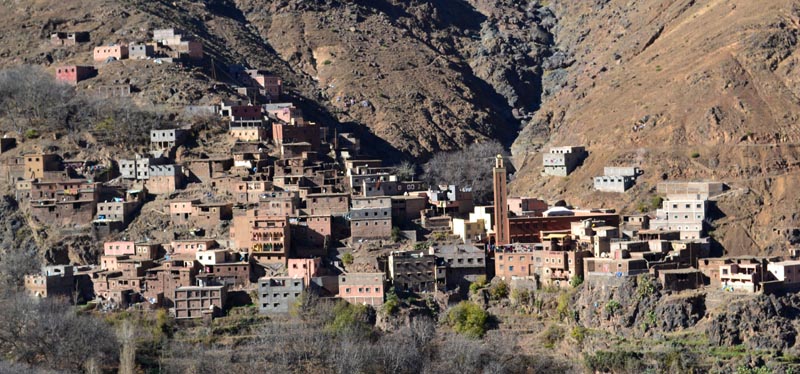

Figure 3: One of the many small villages perched on the mountainsides over the valley of Imlil, High Atlas

The High Atlas

In the High Atlases near Marrakesh, I went on a hike against my better judgment. This judgment, as always, begged me to grab a book, a cup of coffee, a few too many blankets, and curl up in front of the beautiful panoramic view of the aptly named Panorama Hotel. But, alas, I ignored my judgment.

Ignorance: that is the idea we’ll discuss here. To ignore, to not read the signs, to not know how to read the signs, and perhaps even to not know how to read at all: we’ll get to all of these, though I fear we’ll skim over them, because this is a blog post and I don’t have the time to spare in my year-long sabbatical or the knowhow to do anything more elaborate than skim over the surface of this concept.

In Fes, our tour guide showed us street signs in the medina. Some of these were written in three languages: Arabic, French, and Berber. The last of the three is the one that is most interesting, mainly because the Berber language (or, to be more precise, Standard Moroccan Berber) received official status in Morocco just nine years ago in 2011 as part of the revised constitution.3 Berber languages are primarily oral, and until recently did not have a formal written form though the first inscriptions in Berber date back to the second century BCE.4 In part because they have a predominantly oral tradition and because the groups who speak Berber languages were traditionally nomadic, there are strong dialectic differences among the various forms of Berber. And yet, the street signs in Morocco seem to distill this complex tradition into the platonic geometries of this written form.

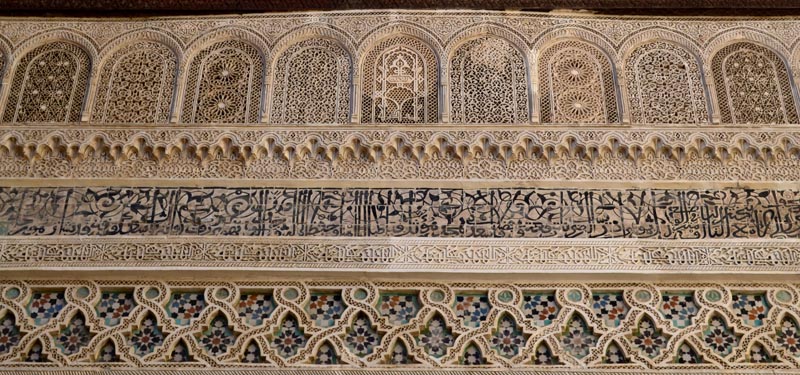

Figure 4: Detail in Cherratine Medersa, Fes

When I was first told of the integration of this language into the fold of Morocco’s linguistic makeup, I saw it as such a pure expression of the intention of integrating this culture into the fold of what it means to be Moroccan. But the reality is not that harmonious. It took a five-hour hike for me to realize the extent to which it is not all that harmonious.

Picture this: mountains surround a valley freckled with earthen houses, tipping dangerously over rough folds of rosy earth, dusty golden brush, the crisp December sun-kissed wind, and over all of it, the never near enough snow-capped ridges of the Toubkal—and then there’s me, face like a pink marshmallow, fingers the size of sausages, knees wobbly, worn city sneakers slipping and sliding, and three layers of sweaters wrapped around my waist like I’m trying to bring back the nineties. Sure, I wasn’t a pretty sight, but I didn’t let that stop me from keeping up a lively conversation with our guide who (bless him) didn’t stop asking if I needed to take a break.

As we passed a sign, I noted how it was only written in French and Arabic. Strange that it’s not written in Berber, I said, seeing as the people who live in the valley are Berber.

Not so strange, my guide said, keeping his stride in an unbearably nonchalant I-do-this-for-a-living kind of way. The sign is there for the tourists. And anyways, no one in the town would know how to read it if it were written in Berber.

I pressed him. He explained how the language was still taught orally from generation to generation. Families spoke in Berber at home and amongst themselves, but very few knew how to read or write it (the majority also spoke Arabic, French, and even English, because tourism was the primary source of business of the townspeople). This brings me back to the Barthian myth, which is like a double helix of signification, a second (hidden) layer of meaning interlaced with a first (more obvious) one. Let me explain: the signs written in Standard Moroccan Berber script express an idea—that the Moroccan cultural identity can encompass and celebrate the identities of the various peoples that inhabit its lands and that integration is a possible and positive solution to the divisions that once marked society. But of course there is another layer of significance that is hidden in these signs: that in creating and imposing a standard and written Berber language, something essential about Berber culture is being buried, namely that its expression is neither standard nor written.

We need to learn to read the signs. Not just the messages they intend to speak but also the ones they accidentally whisper. Illiteracy. On first read one will almost inevitably assume that it is something to be remedied, a social evil to be eradicated. And in many ways this is a logical truth. But here in the mountains outside Marrakesh I found that literacy didn’t sprout solely from the pages of a dictionary and that one was not illiterate simply by virtue of not knowing how to read a book. Just as quickly, I also found myself doubting my own literacy, my own ability to read. But the fact remains that the only thing I truly know how to read is that which has been abstracted for my understanding, simplified into narrow messages, and spoon-fed by way of a language that speaks in concepts I have learned to accept as truths.

And when it comes to integration, be it that of the Berber peoples that live across North Africa or the refugees flocking across Africa toward the northern coast, it is essential to deal with the idiosyncrasies of the modes of thought on a fundamental level instead of applying a single mode indiscriminately across the surface of life. That is the difference between integration and assimilation, a difference that is easier identified from afar than upheld in one’s own life.

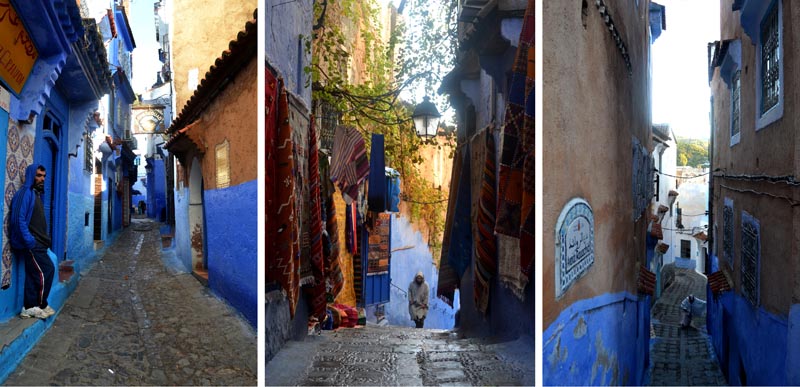

Figure 5: Street scenes in the medina of Chefchaouen

Blue is the Warmest Color

Chefchaouen is a small town in the Rif Mountains halfway between Tangier and Fes. It’s got the kind of paint job that the neighborhood kid down the street would do. You know the one, the one that’s got eyes like the surface of one of those sandstone canyons in Arizona. He gets roped into painting his parents’ garage. He gives up halfway up the wall, a look his parents leave in a naïve attempt at teaching the kid a lesson. In the same do-it-yourself fashion, the brilliant blue of Chefchaouen’s walls reaches up over the sun-tanned walls in staggered blocks, marking a sharp contrast with the rough natural texture of the upper stories. Sometimes it does reach the roofline, giving all sufferers of OCD a moment of relief. Other times, you get a wonderful gradient of blues, the distinct hues layered up over each other with the historical beauty of the rings in a tree trunk.

This blue tells an unexpected story. Until the 1930s the town was actually whitewashed with green doors typical of Muslim towns. The blue paint that currently adorns the walls is a 20th-century addition, a recreation of a 15th-century touch by some of the town’s first settlers.

Figure 6: Place El Haouta in Chefchaouen

Figure 7: Street scenes in the medina of Chefchaouen

Half of the charm of any mountain town comes, unsurprisingly, from the setting. I can only imagine such a setting as the Rif Mountains would have had on the people who decided to make it their home. The peaks that surround Chefchaouen are not only the namesake of the town but also a source of refuge for various groups. These peaks were once the base for the Berber tribes fighting the Portuguese invasion. Then in 1471, displaced Andalusians founded the city of Chefchaouen into the mountains. These refugees were some of those Muslims and Jews expelled from Spanish Iberia as part of the religious cleansing of the peninsula after its unification under Christian rule.

Whitewashed as it once was, the town can be easily confused with any one of the white towns in Andalusia, built into the cliffs near Cadiz and designed with a similar urban character. This isn’t surprising, seeing as what is now Andalusia was the epicenter of Al-Andalusian power before the Spanish took the region in the 15th century. When the refugees settled in Chefchaouen, the Jews used blue as a way of differentiating their homes from those of the Muslims, who painted their doors green in order to mark their own individuality. Nowadays, the Muslim population has wholly outnumbered its Jewish counterpart and the blue has been appropriated by the town as a whole. It serves as a definitive marker of the town’s character in a strangely commercialized derivative of those early refugees’ expression of group identity.

Figure 8: Zaouia Sidi Ahmed Tijani mosque/mausoleum in Fes

A City between Two Riverbanks

It might be sunny outside, but you would never know it from within the maze that is Fes. Chipped walls rise up three or four stories, many of them windowless to the point of bringing out a claustrophobia I didn’t know I had, and the winding pedestrian streets they frame can get so narrow you’d think they were built for that scene in Being John Malkovich. But I won’t let that stop me from getting lost in the city. I scrunch up my American-fed frame and wiggle into the kinder-sized alleyways with the hope that at the other end I’ll find yet another doorframe or fountain or wall, each more beautiful than the last—but what I find is a scene that is downright offensive to the rest of the medina.

Figure 9: Qued Bue Krareb is the river that crosses Fes that once marked the boundary between the Al-Andalus and Kairouan enclaves

No, what you’re looking at is not on the edge of the medina. It’s smack dab in the middle of Fes el-Bali, the walled medina that comprises both banks of the river. The river itself has been encased in a concrete canal and framed by structures that look like an architecture student’s first attempt at 3D modeling. In the background, you’ll even spot that student’s fun afternoon discovering the mesh command. But, believe it or not, this river in all its bygone glory was once a significant juncture in the urban fabric of the city.

The river marked the split between the two fortified cities that are the foundation of Fes. Both cities were the product of displacement. To the southeast lay the Al-Andalus settlement, created by the Muslim refugees fleeing persecution in Cordoba, while to the northwest grew the settlement of those fleeing the Kairouan uprising in Tunisia. (The Kairouan uprising was part of the Berber Revolt that severed Umayyan rule from parts of the Maghreb and Al-Andalus in the early 740s CE.) At the beginning of the 9th century, Moulay Idriss II named Fes his capital, consolidating the two walled cities into one.

Figure 10: Zaouia of Moulay Idriss II is the zawiya (shrine) dedicated to Moulay Idris II, considered the founder of Fes and the man responsible for encouraging the three early refugee immigrations to the city

I spent four hours with a tour guide walking around the city and pestering him about the refugees that founded the city (yes, I have spent the majority of this fellowship pestering people and no, I haven’t made many friends from it). But getting him to acknowledge any influence of these refugees in the urban fabric was like pulling teeth. The division between the two groups barely lasted four years, he kept saying, as if after four years two groups could seamlessly integrate into one. I’m not looking for strife between the two groups but rather any cultural difference that may have marked the spaces they created or evolved within this new setting. The problem, he repeated, was a lack of information. I knew that already. I’d previously pulled the internet’s teeth but only managed to extract a couple half-formed cavities.

According to my guide, the Kairouan refugees from Tunisia were a more introverted people, wealthier but socially and economically insular, while the people of Al-Andalus who came from Cordoba were more extroverted, engaging in more open social and economic exchange. The traces of these supposed characters seem contradicted by the current urban expression one finds in the city. The Kairouan side is vibrant, open, and bustling while the Al-Andalus side is drowsing in the calm day-to-day of an urban residential area.

There are a few notable architectural monuments that remain from the two refugee settlements, none of which are accessible to non-Muslims. Notable among them are two mosques, the products of the vast inheritance of two sisters from Kairouan, Fatima and Miriam al-Fihri. Fatima sponsored construction of the Kairouan Mosque on the western bank and Miriam that of the mosque of Al-Andalus, which was located on the eastern bank and constructed by the refugees from Cordoba.5 I only had the ability to peek into the open gate and catch a glimpse of the courtyards that mark the entrances to these religious centers, trying to imagine the richness, both architectural and literary, that I know hides just beyond those walls. The Kairouan library is considered one of the oldest libraries in the world and—more importantly for me—the great literary legacy of the first refugees who helped found the city of Fes. Due in large part to these two institutions, considered by many the oldest universities in the world, Fes became such a thriving intellectual center while it was the capital of Morocco.

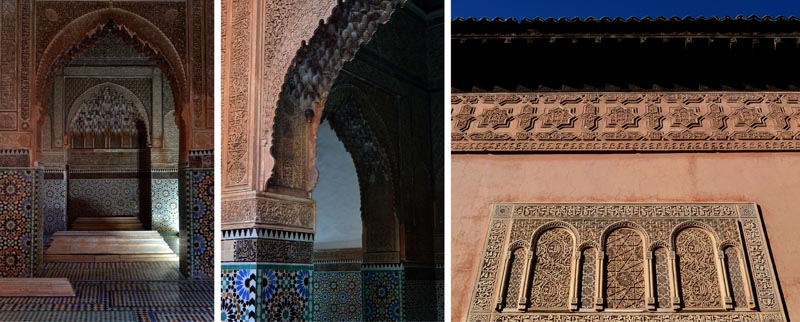

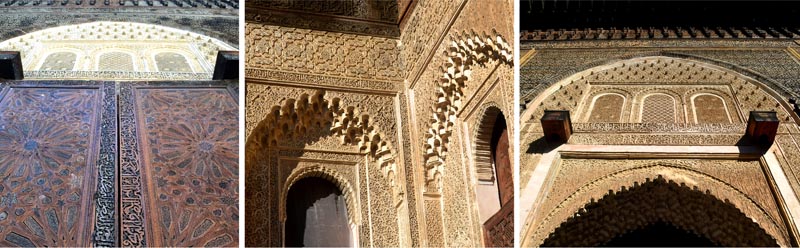

The problem, let me repeat, is the lack of information. But more than a lack of information, it is a lack of information available to me. Without the access to institutions such as the Kairouan University, I am at the mercy of the ever-creative tour guides, some of whom tell historical facts the way my mother tells chismes, with embellishments that border on lies. With that in mind, I’ll give you a few photographs of the beautiful embellishments I found in Morocco because, because if I’m being honest, I myself am easily blinded by the beautiful embellishments that adorn, distort, and hide the world around me.

Figure 11: Plaster and tile details of Saadien's Tombs in Marrakesh

Figure 12: Wood and plaster details in Bou Inania Medersa courtyard, Fes

Figure 13: Doorframe detail of Nejjarine Fondouk in Fes

Behind Walls, On Fire

For the better part of my life I have been caught in a tug of war between my two great loves: architecture and literature. The war erupts with renewed strength at this happiest time of the year. As the year comes to a close, it seems my family wishes to also bring to a close all unanswered questions floating around their lives. I couldn’t tell you why, but it just so happens that my person is the subject of many of these questions. One of them is the following: “After all this, after this year is done, are you finally going to be an architect?” I hear the second question barely concealed within that sentence, which is this: “What are you doing wasting your time writing about architecture when you could be creating it?”

The underlying assumption is that the built world is somehow more than the written one. After this year, I am more certain than ever that both forms of creation have the same capacity to exert power, the same radius of influence, and the same Achilles heels. These heels are what I find most fascinating. As one of my greatest teachers, an Englishman by the name of Kyle Dugdale, would say, buildings, much like writing, can be read. Both are vulnerable to the intention of their creators and the interpretation of their readers. What’s more, these same readers have the power to forget, cover up, modify, and even destroy these creations. Like any creation, they are at the mercy of the people’s whims.

When Queen Isabel of Spain came to Granada, she came with the intention of destroying the imposing Islamic monument that towered over the city. Granada was to be the urban icon of her conquest of Iberia, which meant that the Alhambra had to be torn down. Destruction is a gesture as royal as a crown; the invading power tears down the past expressions of power to build its own future one. Isabel’s mistake was stepping into the Alhambra. Luckily for us, the significance of the Alhambra is easily read in the stuccoed walls, stalactite ceilings, hydraulic system, intricate woodwork, and never-ending network of rooms. The journalist Edward Rothstein called it “a monument to the Andalusian sublime” though not entirely in a good way (for those interested, his psychoanalysis of Andalusian architecture from the New York Times is well-worth a quick read).6 Even Isabel must have had to admit that such a monument belonged in the annals of human history. Instead of destroying it, she made pointed alterations into the existing structure, initially introducing Christian iconography and appropriating the citadel without destroying its essence.

Figure 14: Facade reconstruction at the Mosque of Cordoba

Figure 15: Facade reconstruction at the Mosque of Cordoba

Other times, we don’t get so lucky. Just a kilometer down the hill from the Alhambra, the Plaza Nueva de Granada is an unremarkable square. Pleasant in a very Spanish way, with enough chocolates con churros, cafes con leche, and cañas con tapas to keep any Spaniard contented. In 1499, during the Spanish Inquisition, 5,000 Arabic manuscripts were burned in this square (the numbers, as always, vary from source to source). These books were the product of a period of cross-cultural productivity and harmony known today as La Convivencia. Though the level of harmony that existed at the time is called into question by certain scholars, the wealth of creative artifacts in written, object, and architectural form that still exists attests to the productivity experienced in Al-Andalus during that time.

Many of the books that were burned were from the extensive Islamic collection in the library of Cordoba, which was destroyed in 1013 by the invading Berbers. But not everything was lost. One source notes the Jewish translations of some of these texts survive to this day.7 Another source states that the Arabic translation of Classical Western works contained in that collection was invaluable in the development of Renaissance ideas.8 This later influence depicts the complex forms the legacy of such works can take. Like a phoenix rising from the ashes of that bonfire, that library lives on in the people who managed to read, interpret, and adopt some of its thousands of works.

Figure 16: Oratory walls in the Medersa of Granada

Then there are times when we get ridiculously lucky, as is the case with the wonderful medersa in Granada. If we are talking about glorious displays of phoenixes in flight, this story seems an apt example. Founded by Nasrid ruler Yusuf I in 1349, this center for religious learning was the first university in Granada. When the Spanish entered Granada, the major part of the medersa was torn down. The sole room left was the oratory, a small octagonal domed space, which was covered with wooden sheets and decorated for use as a Christian basilica. Years later, the space was incorporated into the home of a wealthy merchant, who kept the courtyard that fed into the oratory as a showroom for his textiles. On a fateful night, a fire erupted in the courtyard. It spread into the oratory, finally revealing the beautiful plaster and tile work that had been almost miraculously preserved under the wood panels all those years.

And yet, in the end, this is not a story about fire. From the book burning in Granada’s square to the fire in a wealthy textile merchant’s home, we must look through the fire to see what lies behind, but we do so much in the way I had to (and still) look through the opaque walls of Fes. With a restricted, piecemeal, and censured material history at our disposal, the only thing that’s truly visible is the bit I still find the most fascinating. It’s the Achilles heel of my two great loves: the very people who try to read the stories architecture and literature have to tell.

Figure 17: Interior courtyard at Nejjarine Fondouk in Fes. Fondouks were traditional inns in Morocco for traveling merchants and craftsmen. Today, some are open to the public; this one, for example, serves as a museum.

1 Barthes, R. (1972). “Myth Today.” Mythologies (Trans. A. Lavers). New York: Noonday Press.

2 Ibid.

3 Naylor, P. (2009). North Africa, Revised Edition: A History from Antiquity to the Present. Austin: University of Texas Press.

4 Cline, W. (1953). “Berber Dialects and Berber Script.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 9(3), 268-276. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/3628698; Ennaji, M. (2014). Recognizing the Berber Language in Morocco: A Step for Democratization. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 15(2), 93-99. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/43773631.

6 Rothstein, E. (Sept. 27, 2003). “Was the Islam Of Old Spain Truly Tolerant?” New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/27/arts/was-the-islam-of-old-spain-truly-tolerant.html

7 Ramm, B. (June 29, 2017). The 100 year old Arab poetry that lives on in Hebrew. BBC. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20170616-the-1000-year-old-lost-arab-poetry-that-lives-on-in-hebrew

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top