-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

At the Edge of Burma

Editor’s note: We recognize that Burma has been called Myanmar since the ruling military government changed the country’s name in 1989. The author deplores the human rights abuses of the current government of Myanmar, particularly the recent abuses of the Rohingya Muslims, and therefore she chooses to not to recognize the ruling military government of Myanmar. As a result, throughout her article, she refers to the country as “Burma.”

Figure 1: Fisherman on Inle Lake

“Sucede que me canso de ser hombre.” It so happens that I am sick of being a man. This is the solemn first stanza of Pablo Neruda’s “Walking Around.” The poem is in the collection Residencia en la Tierra, an anthology that exposes the poet’s feeling of alienation within his society. Channeling the 19th-century French poet Charles Baudelaire, Neruda proudly wears the robe of the flaneur in this poem, strutting through the city of Buenos Aires with a melancholy that borders on aggression.

Burma is nothing like Argentina, walking around Yangon is nothing like walking around Buenos Aires, and I, to my own chagrin, am nothing like Pablo Neruda. Or perhaps the difference is not so clear. Both countries, for example, were significantly marked by colonial influence, both cities show the architectural expression of that influence, and both Neruda and I (along with a large and unhappy portion of humanity) attempt to see oceans within the buckets of water around us. So perhaps it’s not so strange that I find myself drawn to this particular poem as I begin to make my way through Burma. Walking around Yangon, I can’t help but read lines out of that poem in my head. In them, I see Neruda struggling with the character he was playing in his day-to-day life. He was struggling with the sterility of his bureaucratic job and went searching in the dirtiest recesses of his city for a more honest expression of life.

What do you see when you escape the frame of your everyday? It doesn’t take much, a wrong turn, an extra stop on the train line, an alternate route to avoid traffic. Disengage from your typical and see what you can find in the strange. I fear that what Neruda found was nothing new. No escape, no better way, no way out. Because for him the problem didn’t lie in one space; it revealed itself to his person everywhere he went. For him the problem was held within that first stanza. The problem was “being a man.”

Figure 2: Boat captain taking his daily route across the floating village in Inle Lake

Traveling is on some level a form of escapism, like the Marxist “leisure” in the life of the modern capitalist worker. But just like Neruda, and Marx before him, any traveler will quickly find that there isn’t such a thing as true escape when the problem is as Neruda defined it: being a man. Southeast Asia is filled with long-term travelers living out their escapist fantasies in cheaper beers and emptier beaches. But behind the initial image they find is another landscape, the one Neruda saw in Buenos Aires:

Yo paseo con calma, con ojos, con zapatos,

con furia, con olvido,

paso, cruzo oficinas y tiendas de ortopedia,

y patios donde hay ropas colgadas de un alambre:

calzoncillos, toallas y camisas que lloran

lentas lágrimas sucias.

[I stroll along serenely, with my eyes, my shoes,

my rage, forgetting everything,

I walk by, going through office buildings and orthopedic shops,

and courtyards with washing hanging from the line:

underwear, towels and shirts from which slow

dirty tears are falling.]

Con furia, con olvido. With rage, with forgetting. This line doesn’t translate well into English, especially the way the translator chose to rewrite it. But Neruda traveled with these things. He carried them into these spaces. Neruda didn’t travel forgetting everything, he traveled with his forgetting. Unlike his translator, he was fully aware of his role in the poem and he reminds the reader of that role, so that when we reach the end of his poem we know that the tears that fall from the clothesline are none other than his.

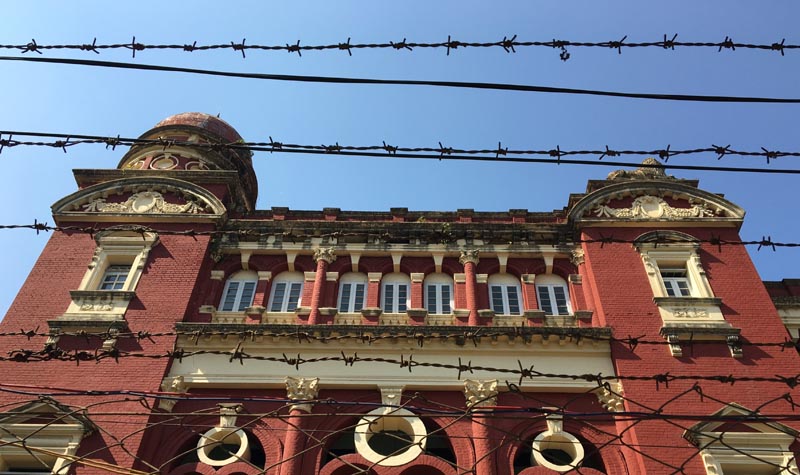

Figure 3: Façade of Regional High Court, a British Colonial building in Yangon

So, when it comes to finding the strange, I think I’ve come to the right place. Yangon is a strange city. British colonial structures crumble above a street scene that is halfway between the insular Burmese city it once was and the globalized city it is becoming. But even calling a city Burmese is strange. The country formerly known as Burma, now known as Myanmar, is a country with over 135 classified ethnic groups and with cultures as distinct as they have been secluded. So to say that something or someone is Burmese is only really admitting to being ignorant of the history of Burma. It is easy to be confused about the naming of the country and its people since the country was virtually inaccessible to foreigners for five decades while under sole control of the military junta. Even now, some areas still caught in civil war are restricted, namely the regions to the north.

Walking through the city, I passed a few hidden mosques tucked away in the urban fabric. I would have never noticed them if it weren’t for the Arabic script drawn into the facades, a single line of text repeated ad infinitum across architecture. My first guess is to think these mosques are the unused remnants of Rohingya Muslim minority whose discrimination, genocide, and expulsion from Burma have elicited international outcry in recent years. But as I look closer I notice a world around these facades, a tense (though perhaps I am the one bringing the tension), unhurried, and vibrant sea of people making their way past the surface of words I can’t help but focus on. Around these mosques at least, Muslim communities still thrive, and with all the recent international attention, they are also beginning to petition for the mosques that had been closed to be reopened.

Each time I stop to take a picture of another mosque I am met with the inquiring look of a local merchant. I do not pass by unnoticed in Burma, not even in this city where every face I see reminds me how multicultural this country truly is.

Figure 4: Selection of facades in downtown Yangon

Figure 5: Colonial-era facades in downtown Yangon

The Border Concept

What does a border look like? That’s a funny question. So funny it almost verges on ridiculous. Because no two borders look alike. More than that, a single border doesn’t last very long unaltered. Geography, climate (political and otherwise), time, and a myriad of social factors fundamentally alter what a border “looks like.” To ask what a border looks like is kind of like asking what shelter looks like. It can look like anything. And yet, in Bagan, somewhere between visiting one and a thousand more temples, I met a Japanese woman who asked me that very question. We got to talking about our travels and I told her I had come to Burma through the Mae Sot–Myawaddy border crossing, one of the few accessible border crossings between Thailand and Burma. Being Japanese and only ever knowing a borderless island, she was curious. In Japan, she told me, when we want to look at our borders, we look out over the ocean and up toward the sky. We never see another country’s land.

In my attempt to answer quickly, I told her a border was like a customs line at an airport. You go in from one side, slip through a vacuum, and come out the other side. But anyone who has walked across a border knows that this comparison is inapt. Like many who experienced the creation of the European Union, I still feel a certain rebelliousness passing over what were once strictly enforced borders within Europe. Like many who have been on either side of an unequal border, I have been forced to acknowledge the stark image of inequality caught in that divided landscape—and how useless an image as powerful as that has been when it comes to creating any change. And, like many who have crossed over a border between warring countries, I have experienced the tension that can be held along a single line. I should have known better than to compare the two, since I have seen enough of both forms of division to know that a customs line, in all its own complexity, looks nothing like a physical land border.

Figure 6: View of fishing boats and houses from U Bein Bridge at the Taung Tha Man Lake in Mandalay

In his theory of “bare life,” wherein he studies those who live outside the judiciary and political frame of society, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben calls refugees “a border concept.” What he means is that the refugees by their very existence call into question the national frame from which they are exempt. That is the conceptual power of the refugee, a power that many theorists who believe nationalism is best left in the past would like to extend to the rest of society. These national lines that divide the earth aren’t entirely stable—nor have they always existed.

The seeming fact of the nation state quickly turns into a question for many who study the situation in Burma. It is as easy as looking back in time. Where once the region of Southeast Asia was a scattering of individual ethnic groups and power bases, now it is a grid of border crossings and ethnic fault lines. In Burma specifically, one need not look further than the accepted tourist destinations to see the breakup of this region. With so many distinct ethnic groups, it is difficult to believe the monocultural tract the current government is still advancing—or is it? It is relatively typical for nascent governments to attempt to unify through a purge of diversity, which can even happen in a new democracy, as is the case in Burma.

Figure 7: Narathihapatae Hpaya Temple in Bagan

The Image of Unity

The Buddhist temple has become the icon of Burmese identity in Burma. With a large majority of Buddhists in the country, it serves as a powerful image of their community and values. This is problematic, of course, when considering the Christian and Muslim minorities whose identity and way of life has been disregarded and whose people have been persecuted by the national government. The fact is that Burma has a history of ethnic conflict that predates the colonial period. Though not specifically termed “ethnic,” the distinct groups within the country have long battled over land and power. The “ethnicity” element of the conflict is intimately tied to the colonial period, when the English came and designated five categorical classifications to separate the people of Burma.

It is interesting to think of the history of Buddhism in Burma. Ironically, it is quite multicultural. One early form of Buddhism that took root in the country is Ari Buddhism. It was highly influenced by Hinduism, Mahayana, and Tantric Buddhism, as well as naga worship, both in ideology and imagery. The significance this form of Buddhism had in what is now Myanmar attests to the mixture of Indian, Chinese, and Sri Lankan influence on the people of this region at the time. This mixed aesthetic can be seen across Burma in the various temples, stupas, and pagodas that dot its surface from north to south. Bagan was the capital of the first unified Burmese power, the Pagan Kingdom, which ruled over what is now Myanmar from the 9th to the 13th centuries. Within this kingdom, before the more orthodox form of Theravada Buddhism took root in the 11th century, the more unrestricted Ari Buddhism predominated. Some of its structures can still be seen in the thousands of religious structures in Bagan.

One historian notes influences from both India and Sri Lanka well into the 11th century in Bagan. As Win Than Tun writes, “Some changes, such as the increasing popularity of small buildings in the later period, certainly must have been connected with Pagan’s contacts with Sri Lanka and thus with the change in the Sangha…The change from the predominance of stupa over temple in the early period to the ascendancy of temple over stupa in the later period as well as the change in painting style very probably resulted from the influx of Indians.”1 Nowadays, biking through Bagan’s immense landscape of stupas, temples, and pagodas, it is easy to lose track of which structure is which and when each was built. Even with a keen eye for detail, the mirage-inducing sun will quickly make you its next victim.

In a country where religion has been a source of so much division and violence, it is sobering to remember the origins of these distinct faiths weren’t as pure as some may think. If we look back far enough, we find a mix of people, ideas, beliefs, and imagery that attests to the interconnectedness of such a universally human part of life as faith. Within such a light, the Buddhist structure serves as a beautiful reminder that even when we are most divided, on some level we will always be connected—if only in history.

Figure 8: Sunrise in Bagan

Figure 9: Sunset in Bagan

But the complexity of the Buddhist structure within Burma doesn’t stop at aesthetics. The Sule Pagoda in the urban center of Yangon is—much like the city it inhabits—strange. It acts more like a roundabout centerpiece than an integrated urban community space. It reminds me ever so slightly of the many roundabouts along Madrid’s Castellana Boulevard, whose arches, fountains and statues serve as historical monuments, tourist-photo backgrounds, and little else. That’s the danger of the roundabout—what do you do with that leftover space? In Yangon’s downtown grid, the central roundabout became the unlikely and uncomfortable space for a temple. Surrounded by a circle of shops, it looks more like a football stadium than a religious monument. The only architectural elements that reveal its role are its golden roofs, which poke out behind power lines, shopfronts, and street signs. And even in its anonymity this is the symbolic unifier of Yangon’s (Buddhist) identity, as cardinal points across the nation are measured against this site. It was also the site of the 1988 uprising and the 2007 Saffron Revolution, as well as the massacre that occurred during the latter.

Like any person interested in the links between space and society, I am drawn to spaces of rebellion, especially those that occur where the power structure is heavily articulated. A single glance around the Sule Pagoda and any notion of an indivisible power structure dissipates before your eyes. Governmental buildings stand back against a powerful crowd moving before it; the pagoda hides behind layers of living, breathing infrastructure; and the old colonial buildings seem to disappear into the background. As always, I am carrying too much with me to paint an honest picture, and the impression of a first glance is nothing against the fact that most crowds don’t transform themselves into a power of revolution—they get transformed, at which point they do not act, but serve.

Figure 10: Street view of Sule Pagoda in Yangon

When I think about the many displaced groups—Rohingya among so many others—that have been forced to flee persecution and civil wars in Burma, I can’t help but think about these spaces of power, in this case the temple, the capital city, and the border. These refugees are framed, defined, and moved by these spaces of power because their existence as refugees is bound to the power that makes them the exception. So, to make the definition of the architecture of displacement even messier than I have already, here I bring spaces that express the power that makes the refugee into the fold.

Figure 11: Mingun Pahtodawgyi outside Mandalay

In Burma it seems to me that these expressions of power can serve as a metaphor for the complexity of the country—culturally, politically, and ethnically. This complexity, as happens so often, can create cracks, dismemberments, and collapses. Burma is no exception: its complexity, so beautiful, enigmatic, and rich, has been and continues to be fraught with all three creations. So, to finish off, let me speak of one final structure. It is perhaps the strangest one I came across during my time in Burma. In the tourist-ready town across the river from Mandalay stands the monolithic brick structure of Mingun Pahtodawgyi. It is the unfinished project of King Bodawpaya, who attempted to build the largest pagoda in the world in 1790, a goal that his subordinates did not share. The construction project was executed by prisoners of war and was a heavy economic burden on the people in his kingdom, to the point that the project was slowed down until the king passed away, at which point it was left unfinished. One-third of its intended size, the structure that remains standing is as amazing as it is haunting and as impressive as it is pathetic. An 1839 earthquake opened massive fissures to reveal the sheer thickness of the monolithic walls, and laid on another layer of humiliation on the king’s impossible dream. When I struggle with the horrible, seemingly hopeless state of so many displaced people across the world, I try to visualize images such as these, which help to remind me of the weakness of abusive regimes. It might not exactly seem like an uplifting reminder, but it is one that puts any situation into perspective, one that I can always count on to clarify: the historical perspective.

Figure 12: Sunrise from U Bein Bridge at the Taung Tha Man Lake in Mandalay

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top