-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Many Shapes of Postwar Reconstruction in a Divided City

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

War is different than other crises that affect cities like natural disasters or even a global pandemic. War is rooted in the psychological and cultural memory as an experience that is meant to undermine the morale of a society and to ultimately destroy people’s sense of place. In fact, “undermining the morale'' has been an established strategy in warfare since World War I with the advent of air raids. Bombing a city from the air didn’t stop at targeting its military and industrial bases, for the objective was not just to cripple the enemy’s militaristic capacity but to destroy its infrastructure, economy and its housing stock. The goal was to crush the spirit of the enemy by unleashing utter chaos and dysfunction in the city; to stop life in its tracks.

I remember taking the bus to school at the age of sixteen, three years into the Iraq War and looking out the window and being fascinated by the site of destruction in Baghdad. I snapped a few photos with my old Nokia phone of a destroyed mosque (I even found the images, see Figures 73–75 at the end of the post). The site of destruction remained with me in the way it challenged what’s real or possible. A destroyed landscape is saturated with past social and cultural experiences, among which is the event of destruction. Rebuilding takes on more than just answering to the practical and aspirational needs of a conventional architecture project. The disruptive force of war forces the urban environment to choose between preserving the past and looking forward. If war is personal, then so is the way we rationalize rebuilding.

Reconstruction might be concerned with immediate and basic needs such as providing housing or clearing the rubble but is largely shaped by more abstract notions like national identity and people’s sense of place, exhibited in embraced or rejected architecture styles and urban forms. Whether the need to rebuild is driven by a political and economic ideology, a desire to break from the past, an opportunity to correct certain problems in the urban landscape, or providing solutions to a housing crisis, the process of reconstruction cultivates an image that evokes national associations between people and their environment. Governments, politicians, planners, etc., rely on these images to advance proposals of what replaces a destroyed site. Berlin’s urban landscape is an embodiment of the many images that were at the heart of debate following the war and the ascent of the Berlin Wall.

There is no one dominant approach to post-war reconstruction that describes the way Berlin has been shaped since the end of World War II. An amalgam of influences contribute to the diverse forms of rebuilding. The most important factor is Berlin’s status as a divided city. After the end of a gruesome war of air raids and bombs, Berlin’s urban landscape became the physical and symbolic site for the political and ideological war between East and West. Architecture and ideas about reconstruction followed along this ideological divide. Following 1945, many architects, planners, politicians, and citizens sought to distance themselves from the monumental neoclassical architecture of the Nazi regime. Furthermore, Jeffry M. Diefendorf discusses in his book, In the Wake of War, much of the debate about post-war reconstruction was influenced by arguments of different architectural styles that existed pre-war and that ranged from modernism to traditionalism.1

Postwar architects and planners grappled with the concept of “Zero Hour,” Germany’s attempt to completely break with its Nazi past after the war, which included the style of architecture embraced by Adolf Hitler and his architect Albert Speer. Diefendorf elaborates that explicit monumentality of Speer’s architecture was not the only thing that was rejected at the time: “The deficiency of imaginative postwar architecture also resulted from the catastrophe of the Nazi experience, which ultimately and thoroughly discredited not only neoclassicism but also the ideas of monumental and representational buildings.”2

Modernism was also a contested style in postwar Germany. Modern architecture had already existed before the war, exemplified by the work of Walter Gropius and the Deutcher Werkbund, but years of the Nazis’ attack on modern art and architecture had limited its growth and popularity. Additionally, there was a movement of traditionalist architecture in Germany that was concerned with questions of historic preservation against the forces of industrialization that swept 19th-century cities. The Heimatschulz movement (the word literally translates to homeland protection), which advocated for traditional styles, believed German architecture “must be organically derived from the German landscape, climate, and historical traditions.”3 The forces of modernization and historic preservation are among the most critical challenges in almost every city, but in postwar Berlin, years of division between east and west and Germany’s continuous struggle with its tainted past complicate the questions of reconstruction. Brian Ladd describes this infliction in German architecture in his book, The Ghosts of Berlin: “German architecture and urban design cannot escape the crisis of German national identity.”4

Some of the questions I was asking myself as I explored Berlin: When does reconstruction actually begin and end? What part of the past is told? Whose past is told? Do we recreate the past right before the war in faithful detail? Do we recreate a different past? Do we preserve the present as a memorial to the war in the form of ruins? Do we see the war as an opportunity to modernize the urban landscape and replace it with a completely new style?

Reconstruction as Political and Ideological Instrument of the Cold War in Divided Berlin

When the war ended in 1945, Berlin’s devastated landscape became the site of another form of confrontation between the East and West. Instead of one Berlin, there were two and each side claimed that theirs was the real Berlin. Before the Wall formally and physically divided the city in 1961, the governments of East and West Germany used architecture and urban design to express their political and ideological philosophies and to facilitate the creation of two separate German identities.5 Nowhere are the competing identities more pronounced in the city than in the housing developments of Stalinallee in east Berlin and the Hansaviertel in west Berlin.

Soviet and Western forces used postwar development to solidify their diverging ideological and political identities in the form of ambitious and innovative architectural models that each regime deemed fit for the reconstruction of their new capital. Both regimes embraced modernism as the language of new Berlin at first, but the GDR soon rejected the style in lieu of the monumental classicism typical of Soviet architecture. After the German Democratic Republic was founded in 1949, it initiated the development of one of the most bombed out districts, Friedrichshain. The major part of the project is Stalinallee Boulevard (Karl-Marx-Allee now). Stalinallee is one of the most emblematic projects of the GDR. The boulevard is 90 meters wide, 3 kilometers long, and extends from Frankfurter Tor to Alexanderplatz in Mitte. It is lined with monumental apartment buildings decorated with architectural tiles. The GDR envisioned Stalinallee as a dynamic boulevard that allowed the mingling of living, commercial, and leisure activities. Commercial uses occupy the street levels of the apartment buildings and the width of the boulevard was to accommodate parades and celebrations. Now the boulevard is dominated by traffic noise of cars zooming in and out of its wide lanes.

I started my walk down the boulevard from the Frankfurter Tor. The prominent twin towers on both sides of the boulevard designed in the Stalinist classicist style by Hermann Henselmann mark the entrance into the long stretch of the project (see Figure 1). Following the domed towers, one might notice a deviation in the street façade from the monumental Stalinist architecture; unadorned, modern looking, five-story apartment buildings stand behind a row of poplar trees. Before the GDR opted for the socialist classicism of the Soviet Union, modernist architects like Hans Scharoun were retained by the Soviet sector for the reconstruction of Berlin. These apartments were designed in the modernist style of the 1920s and were a part of a bigger plan led by Hans Scharoun and his associates to reconstruct the new Berlin (see Figures 2–3).

Figure 1, twin domed towers at Frankfurter Tor, Hermann Henselmann, Karl-Marx-Allee

Figure 2–3, Arcade Houses, Karl-Marx-Allee

However, after construction started on these buildings, a change in the planning of Stalinallee occurred when a delegation of architects and planners travelled to Moscow and other cities in the Soviet Union to study their architecture and urban planning. The results were presented in the manifesto “Sixteen Principles of Urban Planning” that sought to unify the urban design and architecture of the GDR with a language that is consistent with Stalinist style of other Soviet cities. The rest of Stalinallee pivoted quickly to implement a different style that emphasized monumentality, ornamentation, hierarchy and centralization. Modernist architecture was deemed decadent and capitalist. Hence, a row of poplar trees were planted in front of the modernist five-story buildings to hide their facades. From Frankfurter Tor to Strausberger Platz, stands one of the most representative forms of political propaganda as architecture in East Berlin. Meant as an architectural model for postwar housing, it couldn’t be replicated elsewhere in Berlin as the buildings were expensive and unsustainable to build ( see Figure 4–8).

Figure 4–8, Karl-Marx-Allee, 1950–1959

After Nikita Khrushchev’s ascension to power, the process of de-Stanlinization constituted the third shift in architectural style along the boulevard in the 1960s, starting from Strausberger Platz to Alexanderplatz. The boulevard was renamed Karl-Marx-Allee. Khrushchev criticized Stalinist architecture for its lavishness and inefficiency and embraced modern building aesthetics. Brian Ladd adds, “the best way to house the masses, he argued [Khrushchev], was to develop prefabricated industrial forms for apartment buildings”6 Thus, modern architecture made a comeback on the socialist boulevard (see Figures 9–11). The new buildings were simple rectangular boxes of concrete and steel but matched the scale and façade pattern of existing buildings.

Figure 9–11, Karl-Marx-Allee, 1959–1969

The first phase of Stalinallee (1952–1954), was the first major reconstruction project after the war that addressed the challenges of postwar urban planning and housing shortage. It was advertised as the GDR’s showcase of what a newly rebuilt East German city would look like. Not surprisingly, a year later, the West German government promoted the International Architectural Exhibition Interbau for the reconstruction of the residential district of Hansa, adjacent to the Tiergarten, which was completely destroyed in 1943. The Interbau 1957 invited the pioneers of modernism to submit their ideas for the planning and design of a housing project for the Hansaviertel in the International Modernist style, which was professed as the style of a democratic Western society. Plans to rebuild the Hansavietel were discussed since 1951 as the city was suffering considerable housing shortages. Like Stalinallee, West Berlin’s government sought to put their city on the map as the site of innovative architectural designs for the new West German city.

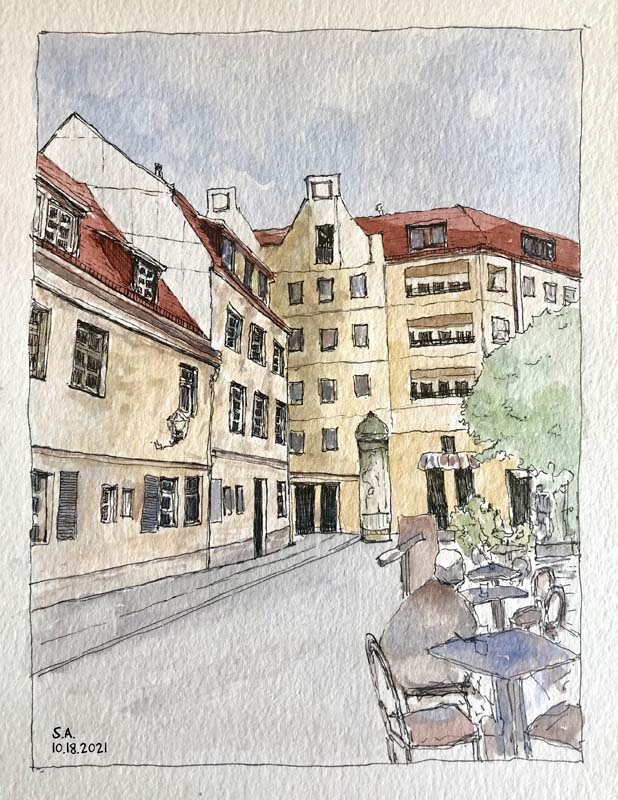

Figure 12, Sketch by Sundus Al-Bayati, Hansaviertel, building by Egon Eiermann

The Interbau 1957 included designs by the most prominent architects of Modernism such as Walter Gropius, Alvar Aalto, Egon Eiermann, and Oscar Niemeyer. One of the most popular events at the Interbau was The “City of Tomorrow” exhibit. It presented drawings and architectural models that disposed of 19th-century notions of city planning such as dense housing, narrow streets, and the mixing of working, living and commerce. The war presented Berlin with a new beginning. The city of the future will be ordered, decentralized, healthy and democratic. Towers of residential blocks will be scattered in a green landscape that will ensure access to light, air and greenery for all. The “City of Tomorrow” was to be found on the grounds of the Hansaviertel.

Figure 13–14, Hansaviertel, Building by Walter Gropius

Figure 15, Hansaviertel, Building by Alvar Aalto

Figure 16, Hansaviertel, Building by Fritz Jaenecke

Figure 17–21, Hansaviertel, Building by Oscar Niemeyer

Figure 22, Hansaviertel, St. Ansgar, Building by Willy Kreuer

It felt good to finally step inside a realized utopian modernist project, to be that scale figure that is dwarfed by the tall towers in the landscape. I noticed the decibel level drop down when I walked deeper into the neighborhood. As I looked up at the curvy apartment building by Walter Gropius, I imagined that it must be pleasant to live there, among all the trees, with a view of the Tiergarten. The Hansaviertel surely looked different from the rest of Berlin. Like the first section of Stalinallee, its planning and construction proved too expensive and complex to replicate elsewhere in the city. It remains, like Stalinallee, an architectural model for postwar reconstruction that envisioned a new urban identity for Berlin. In 2022, the city of Berlin will propose both Karl-Marx-Allee and the Hansaviertel to the “Tentative List” for UNESCO World Heritage as unique examples of postwar development projects that occurred concurrently to address the challenges of reconstruction.

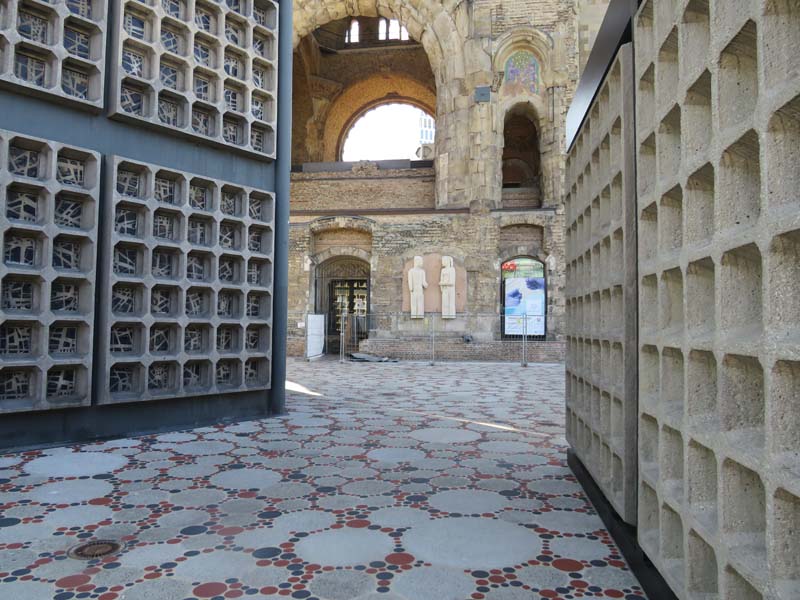

Nikolaiviertel: Recreation of a Medieval Quarter and the Question of Historic Preservation in Postwar Reconstruction

A short five-minute walk west of Berlin’s biggest commercial center, Alexanderplatz, sits the historical Nikolai Quarter in the district of Mitte, recognizable by the two towers of St. Nicholas Church at its center and its narrow winding alleys with small cafes and restaurants that are a popular tourist attraction in the area. The St. Nikolai Church is the oldest church in Berlin, dating back to the early 13th century. The alley and street pattern around the church comprised one of the only remains of medieval Berlin before the war. The site was obliterated during the Battle of Berlin in 1945, except for parts of the church and few remains of other buildings. After the rise of the Berlin Wall, the central area of Berlin became a desolate land.

What visitors experience today is in fact a complete reconstruction by the German Democratic Republic during the 1980s. The site remained vacant after the war until the GDR sought its recreation to be completed in time to celebrate Berlin’s 750th anniversary in 1987. From the perspective of historic preservation, this reconstruction was controversial. After the war, the historic preservation and restoration of inner cities in Germany generated a lot of debate about what can be restored, repaired or completely recreated.

Figure 23, Nikolaiviertel, Sketch by Sundus Al-Bayati

The conversation centered on individual buildings, as well as on the historical character of the city core or Altstadt. Architects and planners debated whether only important iconic buildings that were slightly damaged should be restored or if a group of buildings that were razed during the war could be completely recreated to document the historical characteristics of inner cities including the scale of buildings and the street patterns. Some critics argued that reproducing copies of historical buildings that were completely destroyed would create a false sense of history that tries to evade the Nazi era that led to the war and the event of destruction. However, infilling what was destroyed with modern buildings risked destroying the character and the identity of inner cities. Most agreed that a significant historical building that is moderately damaged can certainly be restored and parts of it recreated because enough of the original building’s details remain to guide a faithful reconstruction. Some preservation officials supported the recreation of historically significant buildings even if nothing of the original existed because they argued that these buildings were historic symbols or documents of the past.7

There wasn’t a unified framework that guided reconstruction and historic preservation principles in Germany after the war. German cities either largely opted for modernization, like West Berlin, or varying degrees of historic preservation in rebuilding their Altstadt; for example, Nuremberg adapted a combined approach to preserving its historic core: iconic buildings that were slightly damaged were restored and new buildings were built that matched in appearance the character and scale of historical buildings. The issue of “Zero Hour” remained at the heart of the debate of modernization vs. preservation: whether to acknowledge a break in German’s history after the war and start a new chapter or recreate vanished quarters of the city to maintain a historical continuity that potentially bypassed the uncomfortable chapter of Nazism and the war.

More than three decades after the war, the Nikolai Quarter remained vacant until the East German government advanced a plan to recreate the historical area, which included restoring St. Nicholas Church and rebuilding a whole neighborhood of 17th and 18th century merchant houses that once stood along its medieval narrow streets.8 In this reconstruction effort, motivated more so by competing with West Berlin in preparing for the 750th anniversary celebration of the city rather than historic preservation, the East German government sought to establish a historical continuity that goes back to the Middle Ages, cementing the urban identity of East Berlin as the true German city. Brian Ladd elaborates on the image that the East German government tried to provoke in creating a replica of the Nikolai Quarter in 1987: “…the neighborhood of merchants testified to the vigor of the new middle class at the end of the Middle Ages, rising to power in a feudal society and thus illustrating (in the most Marxist theory) the bourgeois revolution that was the prerequisite of the proletariat revolution that the Red Army brought to Germany in 1945.”9

Figure 24–29, Nikolaiviertel

Visible Ruins

The sight of ruins has historically been a subject of romanticism and nostalgia in architecture and art but this fascination with ruins became more prominent since the 18th century as seen in well-known examples like Piranesi’s etchings of Roman ruins or Turner’s Tintern Abbey. These works illustrate the aesthetics of ruins; their persistence and decay as objects of contemplation. They are often tourist attractions to be walked around and enjoyed as one would with art in a museum. But, how do we engage with ruins from the war? Are ruins just the material manifestation of conflict, a memorial for the destruction or could they play a more active role in telling the story of the city and its history?

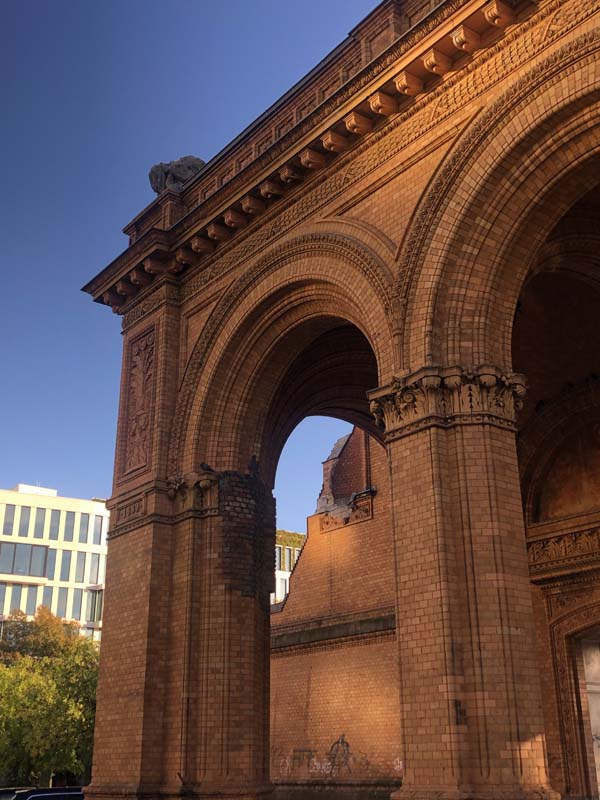

I’ve explored ruins in Berlin and Anhalter Bahnhof’s site and its future use in the Exile Museum stood out as more than a mere aesthetic treatment of ruins. Anhalter Bahnhof was one of the three train stations where Jews were deported from Germany and the proposed Exile Museum will tell their story of exile and other stories of displaced people. On the other hand, Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church situated in one of Berlin’s biggest commercial districts has become one of the most popular tourist attractions for its striking look as a war relic. Similarly, the intricate brick façade of Franziskaner-Klosterkirche is the only thing left standing in this church from the 13th century (see Figures 43–47). Unlike the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, it is tucked away in a park surrounded by trees. Its state of openness as a result of the war is definitely a site to revel in.

Walking in Berlin, sometimes you forget that about half of the city was destroyed in World War II. The scars of war are not as visible anymore. In East and West Berlin, modern planning was the dominant approach to reconstruction after the war. Damaged buildings were rarely repaired or preserved and most were cleared in favor of new modern buildings and wider streets. There are few exceptions that stand out as reminders of what the city looked like after the war for many years.

One of the most famous symbols of Berlin is the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Kurfurstendamm with its broken and hallow spire (see Figures 30–36). The church was built in 1895 and was damaged during the air raids of 1943. In 1961, Egon Eiermann completed a modern addition to the church that consists of a new church and a separate campanile tower. As excited as I was to see a church with a hole in the middle, an actual ruin from the war, my enthusiasm died down as I walked into the area of Kurfurstendamm. How odd did this church and the bizarre modern addition look in the middle of all the noise, traffic and glamorous shops. The ruins stand in striking contrast to the heavily developed and commercial district around it. When the city was divided between the Allies sector and Soviet sector, the Kurfustendamm became a central area for West Berlin and was one of the first areas to be developed quickly to be the most famous Western district for entertainment, business, and shopping. Egon Eiermann’s original competition entry proposed removing the ruins of the church but public outcry led to the revised current design, where still a big portion of the remaining church was demolished to make room for the new buildings. Ruins can be deceiving at times; their shapes suggest how the forces of war struck them but we forget that modernization and profit-driven developments are as powerful as war in destroying the urban landscape.

Figure 30–33, Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church

Figure 34, 1961 church addition by Egon Eiermann, interior

Figure 35, 1961 church addition by Egon Eiermann, exterior

Figure 36, Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church and addition by Egon Eiermann

Another prominent ruin that one might encounter in Berlin is the Anhalter Bahnhof (see Figures 37-42). All that remains of the former train station are the ruins of the main entryway and a portion of the front facade. The station was one of Berlin’s most important train stations and so it was targeted during the war. The building was damaged but it was the period after the war that saw its eventful destruction. Anhalter Bahnhof’s history is closely tied with the history of Berlin from Nazism to the Cold War. In Hitler’s great plan for Berlin, the tracks of the station were severed to make room for Albert Speer’s North-South Axis project. The station would have been demolished in Speer’s project and replaced with a public swimming pool but then the war happened. Anhalter Bahnhof witnessed another crucial historical moment in Berlin. The station became a deportation point for almost 10,000 Jews who were sent to Theresienstadt, Czechoslovakia. The train station remained barely functional after the war until it was closed in 1952 when East Germany redirected all the train lines to Ostbahnhof since Anhalter Bahnhof resided in West Germany. In 1960, the station was demolished in its entirety except for the front portion. In 2025, the historic relics of the station will be part of a new museum that will sit behind it, the Exile Museum. The museum will tell the stories of exile of those who were deported during the Nazi regime and also of current displaced groups. The Exile Museum offers an example of a meaningful engagement with ruins from the war; the historic fragments become more than a romantic picture from the past, detached from any historical, social and political implications but are essential in telling the story of Berlin from their very charged location.

Figure 37–42, Ruins of Anhalter Bahnhof

Figures 43–47, Ruins of Franziskaner-Klosterkirche

Invisible Ruins: Berlin’s Parks

In Berlin, the parks of the city have stories to tell as well. Berlin is a city rich with parks and some of them engage with the history of the war in subtle and striking ways. As you approach and experience the beautiful winding and hilly landscape of Volkspark Friedrichsain and Volkspark Prenzlauer Berg, you might not know that these hills you are walking on were formed from the rubble of World War II. Schuttberg is the German term for a hill made of rubble. After the war, Berlin was covered with mounds of rubble. The task of clearing the rubble and stacking it in piles fell on the women in Germany because of the loss of men during the war. These women were called the Rubble Women. One of the most infamous examples of Schuttberg in Berlin is Teufelsberg. It’s not only a rubble mound that took 22 years to create but underneath it lies the unfinished Nazi training college designed by Albert Speer.

Burying the destroyed remnants of the city after the war under scenic landscapes reminds me of the tradition of Tumuli, mounds of earth and stone that sit over a grave to mark a burial site.

Social Housing from East, West and Unified Berlin

In Stalinallee and Hansavierte, East and West Berlin regimes used rebuilding and the introduction of new housing models as a way to generate new identities for their cities. As discussed, both of these projects were unsustainable to propagate due to their cost and planning. Housing shortages and crowded 19th-century tenement living in both East and West Berlin led to the development of satellite cities outside of Berlin. Unlike Stalinallee and Hansaviertel, there are more similarities than differences in these developments. Both sides used prefabricated mass housing to offer dignified and affordable housing to their citizens that was the opposite of the overcrowded dark tenements in the city. I went to look at a couple of these examples of social housing: Marzahn (1977–1990) in east Berlin and Gropiusstadt (1959–1975) in west Berlin. Literature about these two developments abounds, so I will not get into their history and let the pictures do the work.

Figure 48–56, Marzahn

Figure 57–63, Gropiusstadt

In the 1980s, West Berlin shifted its urban planning approach from modernization to discovering and preserving the 19th-century city. The 19th-century tenement housing that was not accepted in the last three decades after the war suddenly became an important aspect of Berlin’s urban identity. This shift to pre-war architectural styles and urbanity, which was termed “Critical Reconstruction,” emerged during the International Building Exhibition in 1980s. A number of well-known international architects were invited to design housing projects in the center of Berlin as part of IBA 1987. Architects include Zaha Hadid, Aldo Rossi, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman, among others. Pictures of some the buildings I explored are below.

Figure 64–65, IBA 1987, Bonjour Tristesse, Alvaro Siza

Figure 66–68, IBA 1987, John Hejduk

Figure 69, IBA 1987, Raimund Abraham

Figure 70, IBA 1987, Zaha Hadid

Figure 71–72, IBA 1987, Aldo Rossi and Gianni Braghieri

Figure 73–75, Photos from my phone, 2016, Baghdad

References

1 Diefendorf, Jeffry M. In the Wake of War: The Reconstruction of German Cities after World War II. Oxford Univ. Press, 1993.

2 Ibid, 63.

3 Ibid, 50

4 Ladd, Brian. The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape. The University of Chicago Press, 2018, pp 234.

5 Pugh, Emily. Architecture, Politics, & Identity in Divided Berlin. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014.

6 Ladd, Brian. The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape. The University of Chicago Press, 2018, pp.186.

7 Diefendorf, Jeffry M. In the Wake of War: The Reconstruction of German Cities after World War II. Oxford Univ. Press, 1993.

8 Ladd, Brian. The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape. The University of Chicago Press, 2018.

9 Ibid, 46.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top