-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

When Organized Crime Organizes a City

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

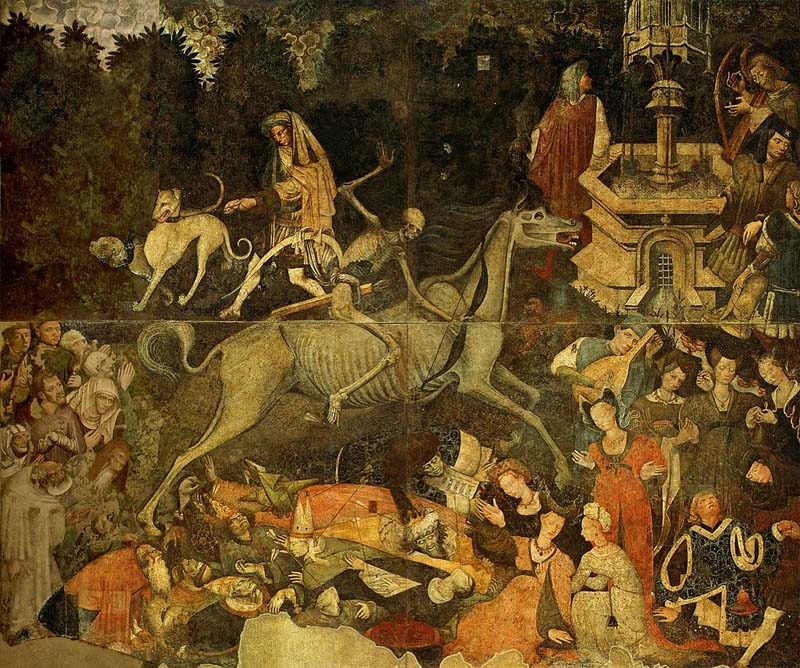

It is fitting that the Triumph of Death painting is displayed in one of Palermo’s many palazzis, the Palazzo Abatellis, where Antonello de Messina’s Annunciation is exhibited awkwardly in the middle of a room. It is unknown who painted the Triumph of Death, a large fresco extending the two-stories height of the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis. Having been engrossed recently in the bloody and grotesque history of the Mafia wars in Palermo, at their height between 1978 and 1993, this 15th-century painting seemed to speak of a grim recent past when hundreds of dead bodies populated the streets of Palermo. It wasn’t long ago that I stood in front of another Triumph of Death painting, the one by Bruegel in the Prado museum in Madrid, painted a century later, and influenced by the Italian version hanging then in Palazzo Sclafani in Palermo. Confronted with Bruegel’s Triumph of Death, I was unsettled by the bleak brown and black landscape that dominates the painting, but the army of skeletons pouring into the realm of the living, some wearing hats or bandanas, with stiff dramatic gestures, felt almost humorous.

There is nothing comical about the Triumph of Death in Palermo. Death is a lone figure, mounted on his skeletal shrieking horse, who jumps out of the center of the painting. The horse is also dead but retains its fleshy mouth and tongue to express its suffering. The well-dressed, beautiful kings and queens suffer calmly as their bodies are pierced with Death’s arrows, nothing like Bruegel’s horror-stricken gesticulating figures running for their lives. The poor and devout either await their turn or have escaped Death’s march, for now. In the eighties and early nineties, the Mafia, like Death on his screaming horse, had triumphed in Palermo.

Figure 1. Triumph of Death, Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo. Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/

Figure 2. Triumph of Death, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Museo del Prado in Madrid. Image from https://www.museodelprado.es/

The Mafia wasn’t an outlawed organized crime group working on the fringes of Sicily. They unofficially ruled Sicily and were allowed and supported to amass political and economic control of the island, because of their usefulness to different groups from aristocratic landowners, politicians in the Italian state whose elections depended on votes from Sicily and the American government in its fight against communism. Because of Mussolini’s repression of the Mafia, it made them look naturally anti-fascist to the Americans who, after the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943, appointed Mafia bosses and made men into administrative and local government positions in Sicily, perhaps not intentionally.1 Nonetheless, this move was crucial in resurrecting the Mafia and allowing it to become an unstoppable system of power that controlled everything and everyone.

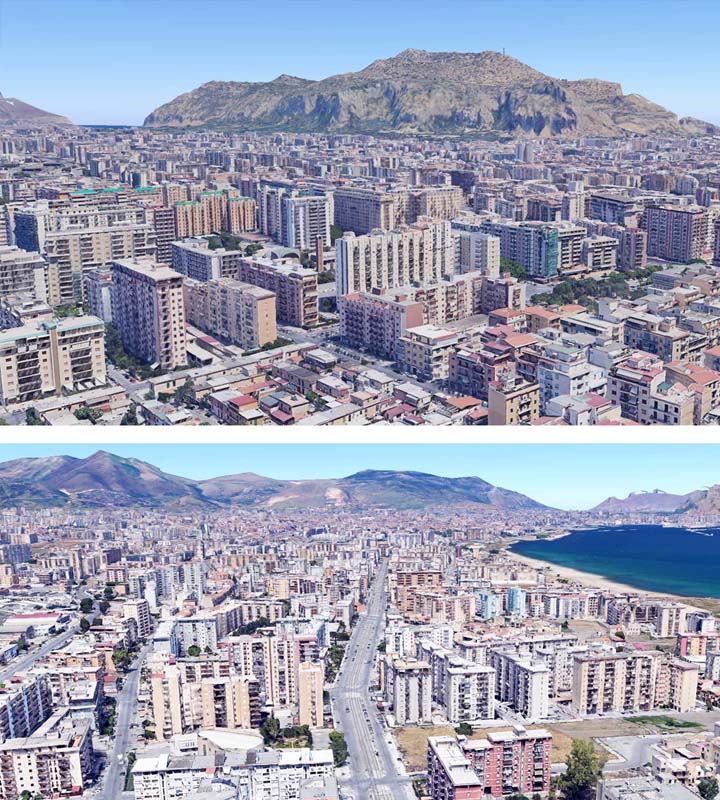

Cosa Nostra’s newly gained political power in Palermo allowed their control of the construction industry and led the rapid destruction of Palermo’s green belt to make room for the acres of concrete that constitute the cheap and grim high-rise apartment buildings outside of Palermo’s historic center. Besides being a way to launder drug money, construction and real estate development also gained Cosa Nostra the trust of the aristocratic class that owned the land around Palermo and were eager to reap the benefits of the Mafia-controlled rapid urbanization of the Conca d’Oro, traditionally agricultural land.2 Additionally, within the context of cold war politics, the Mafia was backed by some connections in the Italian and American governments for their effort in targeting socialist and communist organizers and trade union activists that were gaining popularity among laborers and workers in Sicily for the issue of land reforms that was a direct threat to the Mafia business model that was predicated on feudalism.

I arrived in Palermo at night, and I got a taxi right away. Except for the orange lights of the highway, the darkness hung over everything. I forgot I just landed on an island and was absent-mindedly gazing out of the window until my eyes made out the silhouette of Mount Pellegrino, which took me by surprise. The next morning, I had two simple goals in mind: find some food and go for a walk around the city to get an idea of the place that I’ll be living in for the next month. I stopped at a restaurant near the port and had the pasta alla norma, a classic Sicilian pasta dish made with eggplant and ricotta cheese. I was ready to start exploring.

Palermo’s old city center is close to the waterfront. The harbor was strategically important for the Italian and German air bases and was bombed by five different air forces by the end of the war: French, British, American, Italian and German. The historic center suffered a great loss. Walking by the waterfront, I saw some buildings that still look damaged and yet have merged in their ruined state with subsequent shoddy additions that sit on top of the rubble or to the sides. One of the buildings overlooking La Cala port caught my attention on that first day. Its south wall was covered by a mural of two men conferring and laughing with each other. I wondered who they were but soon forgot about it.

Figure 3. Dilapidated buildings near the port in Palermo’s historic center

Figure 4. The Gothic-Catalan loggia of the Santa Maria della Catena near the Cala Port

Figure 5–7. Foro Italico, a pedestrian path and park in Palermo. Rubble from the destroyed buildings in WWII were dumped into the sea adjacent to Foro Italico creating an artificial beach.

I would later find out that the two men on the wall of the Gioeni Trabia Nautical School building were Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, two famous Sicilians. They were the prosecutors who investigated the Sicilian Mafia in the 1980s and whose work led to the Maxitrial, the biggest effort in Italy's history to bring the members of the Cosa Nostra to justice. It was also the first time the Italian state acknowledged the Sicilian Mafia’s existence as a criminal organization who was responsible for countless murders in the years after the war. Falcone and Borsellino were both brutally murdered a few months apart in 1992 by the Mafia.3 Palermo is full of these opposites: the city of Mafia and anti-Mafia, derelict structures on one block, exuberant Arab-Norman and Gothic-Catalan buildings on another, Mafia-built concrete blocks and monuments to the victims that fought them.

Figure 8. Mural of Falcone and Borsellino on the Gioeni Trabia Nautical School, Palermo.

Figure 9. Piazza della Memoria in front of the Justice building in Palermo named after the victims of the Mafia whose names are displayed on the steps of the staircase. Eleven steel-marble-brass columns represent the magistrates killed by the Mafia.

The Sack of Palermo

Palermo was heavily targeted during the Allied bombing of Sicily between 1941 and 1943. It was the second-most bombed city in Italy after Naples in World War II. Other than Baghdad, which I consider to still be in a state of war, Palermo was the first city in my travels where many ruined buildings from the war eighty years ago still stand. On my way to the Vucciria market, I passed by the crumbling graffiti-covered buildings in and around Piazza Garraffello where a 16th-century fountain, Fontana del Garraffello, somehow survived the bombs that gutted the surrounding structures. In 2014, one of those damaged buildings collapsed even further after heavy rain. Graffiti covers the exposed internal wall of a demolished building and depicts the Fontana del Garraffello with the year 1943 inscribed in the middle of it. Walking a bit further, at the intersection of Via Maqueda and Via Vittorio Emanuelle, known as the Quattro Canti, is a splendid, monumental 16th-century fountain, Fontana Pretoria. Once again, the eye is confounded by beauty and dilapidation. Across from the mayor's office of Palermo and one of the four corner buildings is the abandoned 16th-century Palazzo Chiaramonte Bordonaro, whose restoration began in the 1990s but has been halted since. In Midnight in Sicily, Peter Robb describes the unusual sight of the ruins in the historic center of Palermo on his visit in the 1990s. Thirty years after his writing, some parts of Palermo still display the open wounds of war:

“Other cities have been bombed in the forties, and many worse than Palermo. What was unique to Palermo was that the ruins of the old city were still ruins, thirty years, fifty years on. Staircases still led nowhere, sky shone out of the windows, clumps of weed lodged in the walls, wooden roof beams jutted toward the sky like ribs rotting carcasses. Slowly, even the parts that had survived were crumbling into rubble.”4

Figure 10–16. Damaged buildings around the historic center of Palermo

Figure 17–19. Decrepit buildings in Piazza Magione

Figure 20–21. Fontana Pretoria, Palermo

Figure 22–24. Abandoned Palazzo Chiaramonte Bordonaro across from Fontana Pretoria

What is also unique to Palermo among cities destroyed during World War II is the story of its postwar development, led and controlled by the Sicilian Mafia that irreversibly altered the urban and natural character of the city as well as its immediate surroundings. So destructive was the postwar period between 1950s until mid-1980s for the city that it is referred to as the Sack of Palermo: a story of an elaborate and corrupt alliance of local, national, and international political actors whose interests aligned with Cosa Nostra’s criminal and financial hegemony at the cost of permanently damaging the identity of the city and impoverishing its population. Not long after the war, Palermo was another battlefield. The historic center experienced the most damage during the war to its rich architectural heritage and was completely neglected and left to decay while resources and attention were given to unregulated, Mafia-controlled construction of cheap, low-quality apartment blocks on the city’s outskirts such as Nuovo Borgo, Zen and CEP.5 The green hinterlands of Palermo, known as the Conca d’Oro (the Golden Shell), the citrus plains that surrounded the city and populated with 19th- and early 20th-century Art Nouveau and Liberty Style villas, were largely destroyed to accommodate the Mafia flats. Thus, a large part of Palermo’s natural landscape was lost and with it the livelihoods of the farmers and laborers who cultivated the land and looked after the estates.

One of the main tourist attractions in Palermo are three bustling outdoor markets: Ballaro, Vucciria, and Capo, that are frequented by both tourists and locals. Smells, textures, colors, and the loud noises of vendors and customers overwhelm the first time as one learns to navigate this social scene while wading through stalls of fruits, vegetables, grilled seafood, raw chunks of tuna, shiny swordfish, pane and panelle, and the Sicilian sfincione. The markets are unique not only because they hold on to a tradition that goes back to the Arabs that ruled Sicily, but also because they are the last remaining examples of the local enterprises that encompassed social and economic lives in Palermo’s historic neighborhoods before the war. The poor population that worked and socialized in the historic center were forced into the Mafia housing blocks as their neighborhoods lay in ruins and their livelihoods terminated. Wealthier residents were moved to the slightly better apartment buildings along Via della Liberta.6 The breakdown of socio-economic ties in the city facilitated the domination of the Mafia as more people needed jobs and housing. The bosses were the ones that decided who deserved them. Therefore, the Mafia’s grip of Palermo became stronger as the poorer population began to see the Mafia-built flats a sign of progress and modernization that was badly needed and Cosa Nostra as the main employer in the city.7

“When you walked into the new parts of Palermo it was like walking into the mafia mind. The sightless concrete blocks had multiplied like cancer cells. The mafia mind was totalitarian and even on a summer day it chilled you.”8

Figure 25. Mafia-built housing blocks on the outskirts of Palermo. Images from google earth

A City Endures

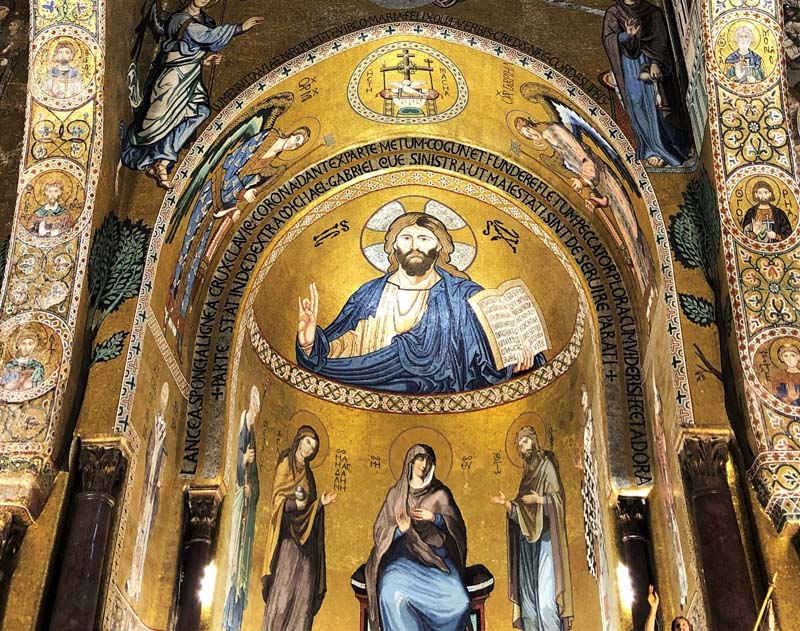

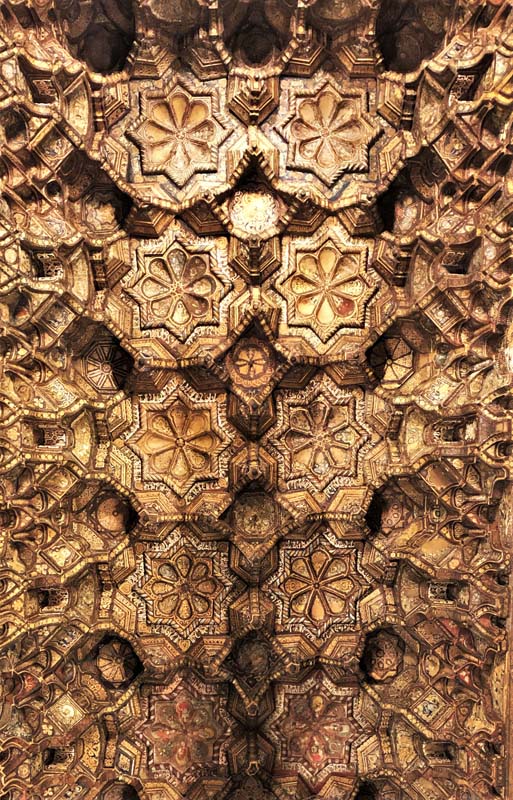

Despite the neglect and damage that Palermo suffered after the war, its rich architectural legacy that survived is a unique mixture of architectural styles I haven’t encountered anywhere else. Arabic, Norman, and Byzantine elements intermingle in the same building. The Arabs who ruled Sicily from 825 until their defeat by the Normans in 1071, many of whom were farmers, improved irrigation systems, introduced land reforms, and were responsible for the growth of agriculture in many Sicilian cities. For the most part, the Normans didn’t drive the Arabs out of Sicily or persecute them for their religion or traditions. Their tolerant rule led to a unique synthesis of cultures that allowed Palermo to thrive as the capital of the Kingdom of Sicily and become one of the wealthiest cities in Europe. The Normans accepted and even adapted some of the Islamic customs and traditions in their art and architecture, as seen in some of Palermo’s famous architectural landmarks such as the Palatine Chapel where dazzling Byzantine mosaics co-exist with Islamic architectural motifs like the muqranas vaulted ceiling.

Figure 26. People lined up to enter the Palatine Chapel within the Norman Palace complex.

Figure 27–28. Byzantine mosaics in the Palatine Chapel dating to the 1140s.

Figure 29. Muqranas wood ceiling in the Palatine Chapel.

Figure 30. Example of the opus sectile mosaics decorating the walls and floors of Palatine Chapel.

Examples of this multi-layered architecture from the Arab-Norman period are seen all over Palermo. One of my favorite buildings is the church of San Cataldo with its three distinguished red domes, combining a rectilinear church layout on the inside with Islamic domes and arches on the outside. It is not until I arrived in Sicily and visited the Palatine Chapel, Monreale Cathedral, and Cefalu Cathedral that I’ve seen such complete, well-preserved and elegant Byzantine mosaics, juxtaposed with opus sectile decorated floors and walls, arranged in star-shaped polygons typical of Islamic ornamentation.

Figure 31. Cefalu, Sicily.

Figure 32. Cefalu Cathedral dating back to the 12th century.

Figure 33. Entry portal of the Cefalu Cathedral.

Figure 34–35. View towards the mosaic-covered apse portraying Chirst Pantokrator.

Figure 36-37. Byzantine mosaics in Monreale Cathedral, Palermo.

Figure 38–39. Benedictine Cloister at Monreale Cathedral from 1200. Pointed arches display diaper work and sit on marble columns decorated with mosaics.

My Airbnb host left me many tourist pamphlets for what to see and do in Palermo and it is precisely this prosperous period of the island’s history under the Normans that is emphasized the most. But between the end of the Norman rule and Italy’s unification in 1870, Sicily experienced more foreign invasions, ending with the Spanish Bourbons who exploited the rich agricultural lands around Palermo and invested their returns in extensive building of Baroque buildings in the city center after destroying much of its medieval architecture.9 Greek, Roman, and Baroque architecture permeates Sicily but it is its Norman legacy that is the most romanticized and connected to a Sicilian national identity. Starting in early 19th century, restoration of buildings in Sicily focused on returning buildings to their Norman image by removing later additions to reveal the “true” Norman form and sometimes reconstructing elements that had long been gone. 10

Figure 40–45. Church of San Cataldo in Palermo, a unique example of Arab-Norman architecture from 12th-century Sicily.

Before World War II, theories guiding the historic preservation of buildings and monuments in Europe began to form in the 1930s as were determined in the Athens Conference of 1931. The principles of preservation that were discussed and promoted for adaptation during the conference were based on minimal alteration of historic buildings and where modifications were required, a conservative and scientific approach informed by data analysis of existing elements were to be implemented. Additions were to be stylistically differentiated from the original.11 The massive damage to cities that was made possible by the evolution of aerial warfare technology during World War II posed unprecedented challenges to the previously accepted theories of historic preservation. In Italy, like the rest of Europe, the strict and conservative preservation rules that were established before the war were thwarted for the sake of saving national heritage. Post-war restoration of historic buildings in Palermo continued the pre-war approach of freeing Arab-Norman buildings of their unwanted pasts.12 The destruction caused by the bombs cleared what stood in the way to further disencumber the authentic heritage of the city. When war destroys a city's history, reconstruction has the potential to re-write it.

Notes:

2 Vincenzo Scalia, “The Production of the Mafioso Space. A Spatial Analysis of the Sack of Palermo,” Trends in Organized Crime 24, no. 2 (2020): pp. 189–208, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-020-09395-7.

3 Peter Robb, Midnight in Sicily (New York: Picador, 2007).

4 Ibid, p.9.

5 Vincenzo Scalia, “The Production of the Mafioso Space. A Spatial Analysis of the Sack of Palermo,” Trends in Organized Crime 24, no. 2 (2020): pp. 189–208, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-020-09395-7.

6 Ibid

7 Jane Schneider and Peter T. Schneider, Reversible Destiny Mafia, Antimafia, and the Struggle for Palermo (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

8 Peter Robb, Midnight in Sicily (New York: Picador, 2007), p.13.

9 Jane Schneider and Peter T. Schneider, Reversible Destiny Mafia, Antimafia, and the Struggle for Palermo (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

10 Giuseppe Scaturro, Danni Di Guerra e Restauro Dei Monumenti. Palermo 1943–1955 (Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, 2006).

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top