-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

7 Final Thoughts

Anne Delano Steinert is a recipient of the 2022 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Over the course of 89 days I visited 27 cities and towns. I arrived home at 11:00 pm on a Wednesday and gave a graduate orientation walking tour at 1:00 pm the next day. My faculty retreat was Friday morning, and school started Monday. Only now, months later, am I able to get the distance from the trip I need to see the big patterns and connect the dots of my experiences.

I have written and rewritten this final report more times than I care to count. At one point it was over four times the word limit! In that process I have figured out that I can’t possibly talk about all the places I traveled or all the things I wondered. All I can do is offer examples of how this trip has impacted my thinking and my teaching. For those of you interested in a chronological catalog of my journey, I provide a list here. As you look at the list, note some of these were just day trips, while our longest stay, in Venice, was almost two weeks.

Here are the places I went:

France - Paris, Versailles, Chartres, Marseilles

Spain - Barcelona

Italy - Verona, Florence, Venice, Cortina d’Ampezzo, Rome, Pompeii, Bari (for the ferry)

Greece - Piraeus, Athens, Tinos, Syros, Santorini

Italy again - Venice, Parma

Austria - Vienna, Salzburg

Hungary - Budapest

Czech Republic - Prague, Kunta Hora

Germany - Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, Bremerhaven, Baden-Baden

France again - Strasbourg and Paris

Here are some thoughts:

1. It is hard to teach a place without seeing it.

I set my itinerary largely to cover European sites I have taught in a “History of Urban Form” course. Though I had seen plenty of images of Athens and Rome, I had never been to either. The impact of finally visiting these places was incredible and I think lives true to H. Allen Brooks’ vision for the fellowship. I am sure this will sound naive and am embarrassed to even write this, but I had no understanding that the Tiber was so narrow or that the Acropolis was so deeply embedded in Athens’ dense urban fabric. Being physically in those spaces has transformed my ability to teach about them and their larger context.

The Tiber River is not very big.

Back when I was in preservation school in the 1990s, the architectural history courses I took with Robert Stern and others were taught to highlight works of architecture as beautiful objects on display, separate from their environment. I don’t think that approach works. I now see how much about these places I failed to understand. When I saw that the Acropolis was part of a functioning city rather than a rarified archaeological site, or that Corbusier’s Unite d’habitation in Marseilles and Berlin actually work as housing in a way their descendants in the U.S. never did, it completely complicated my understanding of the architecture I study and teach and the interconnected continuum of architectural innovation across time.

Corbusier’s Cite Radieuse in Marseilles makes a lot more sense in its Mediterranean context.

2. Buildings need interpretation.

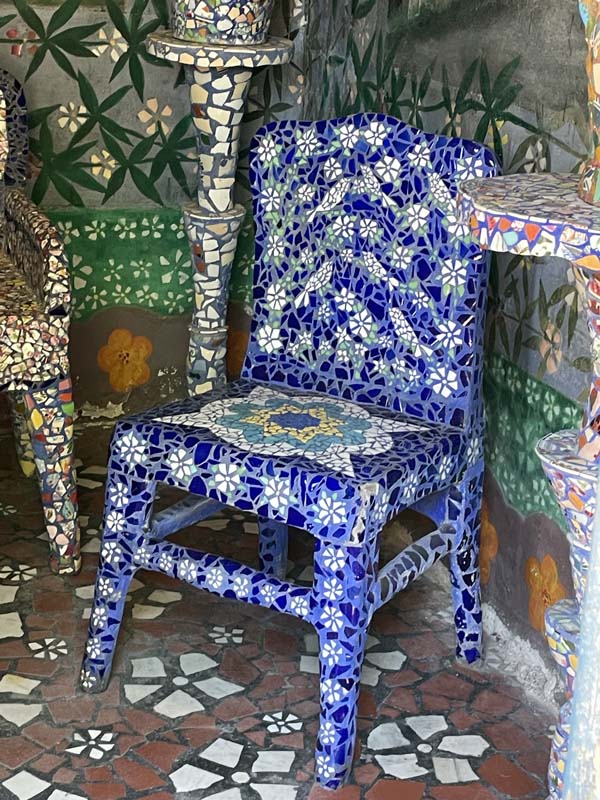

Another goal of my trip was to look for ways the built environment was able to speak or tell its story and/or how people were able to make meaning of the world around them. I had hoped that there were some basic interpretive patterns people use to make meaning of buildings and landscapes and that I could start to catalog or order these strategies. I would say this quest was a pretty significant failure. I traveled with an 18-year-old babysitter and my 12-year-old son thinking that I would observe their process. What I found was an lack of curiosity among these children of the digital age and that, unless there was a very heavy human hand involved (as in Raymond Isidore’s Maison Picassiette in Chartres) their ability to ask questions as an initial step toward investigation was limited.

Maison Picassiette sparked plenty of questions. This photo is a tile-covered chain in the interior. It doesn’t look very comfortable!

I found that without an interpretive interlocutor, most people, sometimes including myself, can’t make sense of buildings. The lesson in this is that we, as historians and preservationists, need to get busy interpreting buildings for people on the streets so that they value and save them. One great example of this is the digital Brno Architectural Manual which I learned about from my new friend, Vendula Hidnkova, while in Prague.1 The site combines architectural information with photos and a map in a digital format accessible from your phone, allowing passersby to learn about architecture in their midst. It seems clear to me that the fields of architectural history and historic preservation need to connect with public history to tell place-based stories in ways that will resonate with a broad public audience. The expertise is already out there if we can bridge our disciplinary silos.

3. People need connections to make places meaningful.

As you would expect, we were able to retain more information when we had something already in our heads to connect it with. In Rome, one of the rare moments my son got engaged in looking at architecture was when we visited the Colosseum. I had him watch a little Kahn Academy movie about the history of the building beforehand, which gave him details he could connect to. I have already written about the Forum light show. He will still say, “I wasn’t really paying attention until they said the Caesar had stepped where I was stepping.” The highlight of his whole trip was seeing buildings in Salzburg where the Sound of Music was filmed. In both places, he was more prepared to make meaning of buildings when he had pre-knowledge to attach them to. My son, Seneca (aptly named for this circumstance), became more engaged when he knew that he was in a space that connected him to historical figure or a beloved, if fictionalized, family chorale. The question then is how we link the history of buildings to things that people already know in a way that is authentic and meaningful and will enrich student understandings rather than merely pile on dates and styles to memorize.

The pavilion where “I am Sixteen Going on Seventeen” supposedly took place has been moved to a public park in Salzburg.

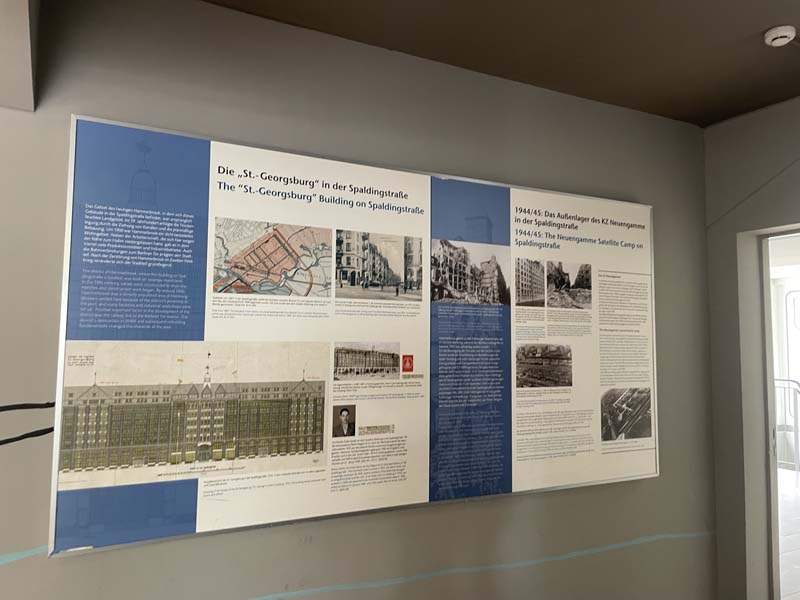

4. Experiencing places where things happened matters.

Most of our students cannot travel to all the places we teach about, and we will always need classroom experiences to bring them to far off places, but we also need to take advantage of nearby opportunities for place-based experience. I have previously written about my experience at the Museum of the Liberation of Rome, and I had similar experiences of a close connection to the past in places like the Ballinstadt Emigration Museum in Hamburg, or even in my youth hostel there, which turned out to have been a Nazi work camp in a previous life.2 Experiential education—the experience of really being in a place where something happened—is an incredibly powerful motivational force that makes education more meaningful and builds connections between student learning and “real life.”

Interpretive panels in my hostel about the building’s previous use as a Nazi work camp.

5. Learning happens best in multi-sensory settings.

One of the most powerful experiences of my visit was in the Jewish ghetto of Venice. I approached the ghetto through a tunnel under a tall tenement. I emerged from the darkness into a sunshiny open plaza where I found scores of Jewish men huddled up in a circle, arms in arm, singing in Hebrew. The moment had an otherworldly feeling, which held on until their tour guide chastised them that they needed to move on. The echoey sound in the enclosed space added a multi-sensory dimension that instantly made the place more powerful. As I toured Venice’s Jewish ghetto (the origin of the word ghetto) with a guide I saw a Jewish retirement home, two synagogues, a Jewish school and shops. These places became more meaningful because my sensory receptors had been opened up by the singing at the start of the tour. I was especially moved by the marks of missing (and extant) mezuzahs on entryways throughout the neighborhood which stood silent witness to the Jews now missing from this place.

A missing mezuzah on a door frame in Venice’s Jewish ghetto.

6. There is magic in ruins.

In a bookstore in Athens aptly named Flaneur, I discovered the book, Walking in Athens, by journalist and photographer Nikos Vatopoulos. This sweet little collection of essays captured everything I loved about Athens (and later Budapest). It is a meditation on the power of ruins and forgotten places. I am always struck by the buildings that seem just about to tumble down—right at the very edge of the possibility of saving. It seems to me that their exposed condition lets me into their secrets and stories. I have been thinking about how to harness the power of ruins to use it with students. I think it is rooted in feeling like you have found a secret and intimate window into the past that may not be there much longer—like you have a special opportunity. Maybe also an element of danger? Or adventure? Could I ask my students to write a paper about why ruins speak to us?

Athens has a wonderful stock of enchanting ruins like this one.

7. Preservationists need to be careful about human connections to place.

Before this trip, I remembered Chartres cathedral as a dark cavernous space pierced with light. Yet, when I visited the cathedral this time, most of the darkness had been replaced by clean bright walls restored by the French ministry of culture to their original appearance as part of a decades-long conservation project detailed in the 2017 New York Times article, “A Controversial Restoration that Wipes Away the Past.”3 For me, like many others, removing the dark layers of dirt accumulated over centuries felt like removing my connection to the generations of people who had visited this place before, laid their hand on a column, and left behind a little oil and dirt which, when combined with candles and incense, covered the building’s interior in a patina of the past. Part of the reason that historic places speak to me, and I think most of us, is that they connect us to those who have come before and remind us that we are part of a continuum of human experience over time. They tell us that we are not alone in the world with our one little life, but that we are a part of something bigger, even a marvel like Chartres Cathedral. I understand that the conservation of the church is what is believed to be best for the stone, that it returns the cathedral to its original appearance, and it allows visitors to see painted details long obscured, but those things come at a cost. I no longer felt like Chartres cathedral was a place I could feel the past humming around me and connect with the ancestors of this place. It now feels shiny and new—which I feel sad about. I know I’m not alone in this. I found this powerfully worded comment on a blog about the restoration, “My wife and I…used to go out of our way to stop-over in Chartres... Even for a confirmed atheist such as myself the cathedral interior was the most spiritual and awe-inspiring building that I have ever experienced and it truly became an inspirational place of pilgrimage for us. We were shocked and heart-broken, indeed out-raged, when we visited last year to find that the French had willfully embarked on this catastrophic campaign of so-called restoration. The result is that now we sadly have no wish to return, as we prefer to retain the memories of this Gothic masterpiece when it still retained the accretions of centuries which were responsible for so much of ifs mystical character.”4 I think that in our quest to save buildings and spaces for future generations we sometimes overlook the connections they hold for people living today.

Partially cleaned pier at Chartres Cathedral showing the contrast between pre- and post-restoration.

These snapshots are just a small fragment of everything I saw and thought about. I am so grateful to have been given the opportunity to take this trip. It will forever impact my teaching and scholarship. Thank you, SAH, and thank you, H. Allen Brooks.

2 The A&O Hostel at Spaldingstrasse 160 in Hamburg.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top