-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The City Designs itself: Tokyo in the Post-War Years

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Architecture of War

The firebombing of Tokyo in 1945 claimed more lives and caused more urban destruction than the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki a few months later. The plan for Tokyo’s burning started 5000 miles away, in a secluded site in Utah desert where the US Army had been experimenting with biological and chemical agents, such as napalm, to ensure effective and maximum destruction of cities and “morale” in both Japan and Germany during the Second World War.1 In 1942, Standard Oil contracted the Czech American architect Antonin Raymond to design a replica of a Japanese middle-class neighborhood for the US Army to test how effectively they would burn once set ablaze by incendiary bombs. The Dugway Proving Ground, where the Japanese Village and its German sister were secretly built, lies to the southwest of Salt Lake City. It was established by the US Army in 1942 as a test site for chemical warfare and included a five-square-mile complex for the precise construction of a Japanese housing block and German mietskaserne tenement apartments, which were repeatedly bombed and reconstructed at least three times. The Japanese Village consisted of twelve apartments of Tokyo’s typical wood construction, complete with traditional interior furnishings, faithfully curated by set designers from Hollywood. Perhaps what is more shocking than Antonin Raymond’s work in Dugway Proving Ground, is that one of the most renowned architects of the 20th century, Erich Mendelsohn, was responsible for the design and construction of the German Village in Utah’s desert.2 Berlin’s cheap and overcrowded tenement blocks housed poor and low-income industrial workers. Debates over inaccurate “area” bombing versus “precision” bombing directed at military bases all but faded in this stage of war as the target in both the Japan and German villages was unquestionably the everyday worker.

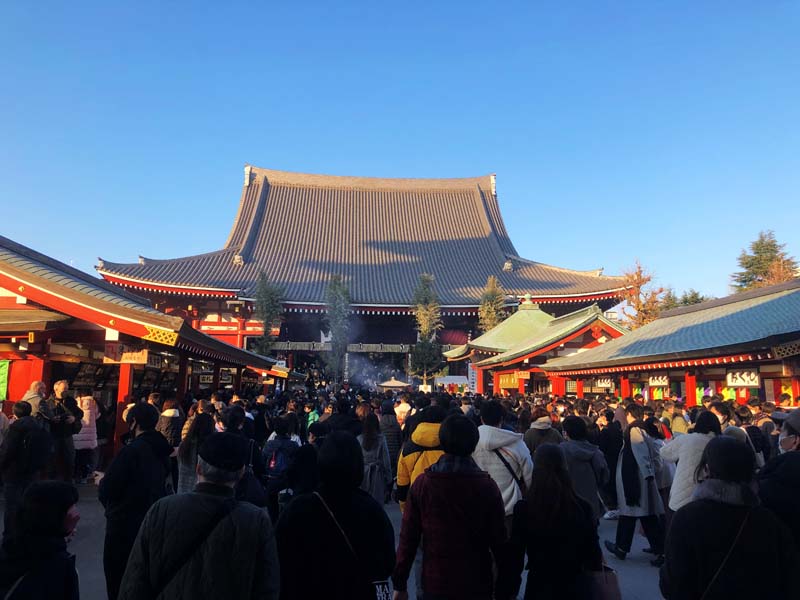

On my first day in Tokyo, I went to the Asakusa district where the popular Nakamise Shopping Street stretches in a straight line from the Kaminarimon Gate to the monumental Senso-ji Temple, lined along the way with shops selling traditional Japanese foods and crafts. Not able to take more than two steps at a time, I slowly made my way through the crowded Nakamise Street, vowing to come another day, not on a weekend, to properly explore this historical quarter. In Edo, as Tokyo was known until the Meiji Restoration of 1868, temples and shrines weren’t only gathering spaces for religious ceremonies and festivities but were also the primary forms of public and green space, equivalent to the role of public parks in a Western city.3 Entertainment districts and commercial establishments flourished near temples, similar to the rows of businesses that form Nakamise Street. During the Meiji Restoration period, public land around temples became the property of the Tokyo Metropolitan government. Commercial establishments along Nakamise Street that were allowed by the Edo Shogunate to set up to serve the large numbers of pilgrims and visitors to the temple were removed and replaced with modern brick buildings.4 These Meiji-era buildings and Nakamise Street were destroyed in the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 and the street was rebuilt again in 1925. Incidentally, this area near the Sumida River was the first to burn when USAAF’s B-29 bombers dropped napalm incendiary bombs over Tokyo, putting their successful chemical experiment at Dugway Proving Grounds into action. The raid, which occurred on March 10, 1945, after midnight, became the deadliest single raid in history claiming the lives of 100,000 civilians and unhousing one million Japanese residents. Nakamise Street and Senso-ji Temple were part of the 16-square-mile area that were engulfed in flames that night.

Figures 1–2. Senso-ji Temple, Tokyo

Figure 3. Five-story pagoda in Senso-ji Temple, Tokyo

The Fires of Edo

A cycle of destruction and reconstruction have historically been a characteristic of Japanese urbanism. Great fires were so frequent in Edo that a popular saying goes: “Fights and Fires are the Flowers of Edo.”5 As Japanese cities were traditionally built of wood and paper, fires repeatedly burned their tightly built neighborhoods to the ground. Despite numerous reconstructions, changes to Edo’s urban form were minimal. As soon as the fires were extinguished, people rebuilt their homes and businesses themselves in the same location with the same building materials, improving little in the process to minimize their losses when the next fire hits. “Indeed, the Japanese seem to have accepted the recurrent advent of urban destruction in general. The location and function of many disaster-battered cities were rarely, if ever, challenged.”6 In general, there is an acceptance of the notion of impermanence as part of the cycle of death and renewal in Japanese culture, found specifically in the core beliefs of the country’s two main religions, Shintoism and Buddhism. The best example of this tradition is found in the cyclical destruction and reconstruction of the Grand Shrine of Ise, Japan’s most sacred Shinto structure: every 20 years, the shrine buildings are destroyed and reconstructed as a way of preserving traditional ways of building and passing on that knowledge to the next generation.

The Great Kanto Earthquake

Twenty-two years before the firebombing of Tokyo in World War II, the city had undergone one of the most catastrophic earthquakes in its history. The 1923 Great Kanto earthquake leveled much of Tokyo when massive firestorms spread across the city, swallowing swaths of Tokyo’s wooden neighborhoods, killing over 120,000 people and leaving two million people homeless. The damage from the Great Kanto earthquake paralleled what Tokyo would experience years later in 1945. Both the 1923 earthquake and firebombing of Tokyo produced a similar burned out landscape that inspired grandiose and idealistic reconstruction proposals that were never implemented as Tokyo’s urban form and planning tradition proved more reluctant to change than other disaster-stricken cities.

Tokyo’s flattened landscape after the earthquake appeared as the perfect clean slate to implement radical plans for a new modern metropolis that expressed Japan’s rise to join the industrializing nations in the West. An elite class of ambitious bureaucrats, politicians, and urban planners proposed reconstruction schemes for a rational city with broad avenues, monumental public buildings, public parks, and green belts that would act as firebreaks to prevent the quick spread of fire that had plagued Tokyo for centuries.7 But the production of a calamity-resistant city was only one part of the ambitious plans for Tokyo’s reconstruction: the earthquake was viewed as an opportunity to recreate imperial Tokyo and eradicate the social ills of industrialization such as the impoverished and densely-built slums that contributed to the fire-prone character of the city. But the overly ambitious reconstruction proposal, led by Tokyo’s Home Minister Goto Shinpei at a budget of 4 billion yen, was contested by government officials and cabinet members who balked at the financial infeasibility of the project.8

Furthermore, strong patterns of landownership revealed that Tokyo wasn’t the clean slate it looked to be after the earthquake. The plan was strongly resisted by Tokyoites who were eager to return to a sense of normalcy by rebuilding their homes and livelihoods as quickly as possible.9 For a traumatized citizenry that had lost everything, the five-year reconstruction proposal was idealistic and disconnected from their immediate needs. Makeshift homes of wood and tin had already proliferated all over Tokyo shortly after fires were extinguished. Eventually, the dream plan for a new Tokyo was reduced in scope to a budget of 700 million yen. The implementation of the plans to reconstruct Tokyo were limited to the process of Land Readjustment where the government was allowed to appropriate ten percent of private land without compensation to widen roads, add firebreaks, build parks, and increase public space to create a more resilient and fire-resistant city. Land Readjustment would later become the dominant planning method in Japanese cities after the war.10

A Second Fire

Only two decades after the destructive 1923 Great Kanto earthquake, Tokyo was a scorched plane again, along with 215 other Japanese cities. Tokyo’s post-war reconstruction didn’t produce drastic or innovative changes to the urban form but was pragmatic and slow as the state concentrated its efforts on expanding the country’s industrial infrastructure and transportation systems to kick-start its broken economy, leaving the rebuilding of individual neighborhoods and housing to the private sector and individual citizens.11 This explains the ad-hoc and eclectic architectural character of Tokyo’s neighborhoods that persist until today. What makes Tokyo such a dynamic city is the constant variation of urban experience as one walks down its streets from intimate residential neighborhoods to narrow alleyways of commercial establishments. The city reflects how its residents adapt and adorn their urban environment with a variety of styles, textures, and ornamental plants and pots that soften the edges of its streets and adds a green element in a city that doesn’t offer a lot of park space.

Figure 4. Typical wood construction in Yanaka neighborhood, one of the few neighborhoods in Tokyo that escaped the firebombing in WWII

Figure 5. Tokyo after March 10, 1945

Although visionary schemes for rebuilding Tokyo emerged before the war’s end, the ideal city was never built. Ishikawa Hideaka, the head of planning of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, proposed an ambitious plan to fundamentally restructure Tokyo and transform it into a network of smaller, population-controlled sub-cities, separated by green belts and parks.12 However, the Japanese government didn’t have the financial capacity to undertake such a radical reconstruction in Tokyo, as many other Japanese cities lay in ruins and required rehabilitation funds as well. In addition, the urban planning tradition in Japan was relatively new, and since its introduction to the Japanese administrative government, was limited to the task of modernizing specific industrial or business centers rather than developing urban regeneration projects of entire districts.13 As an island nation that was closed off to the world for centuries, industrialization and modernization projects didn’t start in Japan until after the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. During this period, national, prefectural, and municipal government functions were established to facilitate industrial development. Government-led modernization projects were primarily concerned with building industrial infrastructure, leaving the rest of Tokyo’s development such as residential neighborhoods to the private sector.14

There weren’t the same contentious debates in Tokyo like there were in European war-torn cities like Berlin or Warsaw over the social and political implications of reconstruction. The post-war plan for Tokyo didn’t hold the same symbolic meanings, and any ambitious plans were significantly curtailed during the first few years after the war in lieu of a pragmatist approach. This is also because Japan was an occupied nation and was restricted from dreaming up massive reconstruction campaigns that glorified the rebuilding of its cities. Instead, the Japanese government continued its pre-war reliance on Land Readjustment procedures that were used after the Great Kanto earthquake to make improvements to the urban environment.15 In addition, persistent patterns of landownership and a citizenry that was accustomed to rebuilding their cities after disaster as quickly as possible mounted considerable resistance to such idealistic schemes that proposed rebuilding beyond the damaged areas of Tokyo.16 Compared to Seoul, where the war resulted in the construction of a completely new city, Tokyo’s reconstruction was rather a continuation of existing, pre-war plans to modernize the city. As a result, planning efforts in Tokyo didn’t go beyond widening and straightening of streets and adding more public and green spaces.

It is essentially the failure to implement a central masterplan for Tokyo’s reconstruction that allowed the city’s many unique urbanisms to flourish and retain some aspects of its traditional urban layout. In my first month in Tokyo, I stayed in the glitzy commercial district of Shinjuku near the world’s busiest train station, where bustling and crowded streets, lined with neon-lit billboards unfold in every direction, tucking underneath a chain of restaurants, bars, claw machine parlors, electronic stores, and other endless shopping opportunities. The administrative functions of the city like the Kenzo Tange-designed building for the Tokyo Metropolitan Government lies in Shinjuku’s business district among a group of other glass skyscrapers. A 20-minute walk away from the station area and Shinjuku’s busy thoroughfares and tall skyscrapers disappear and the city transforms into what feels like a small town.

In one of my walks, I set out to explore the neighborhood of Shimokitazawa, one of Tokyo’s unique neighborhoods that had escaped wartime destruction and had strongly resisted the city’s redevelopment efforts to preserve what had evolved to become a counterculture district that attracted artists, musicians, and anti-Vietnam war protestors. Music clubs, vintage clothes stores, and many small restaurants sit intimately within a residential neighborhood of winding small streets. I started my walk from Shinjuku westward, passing the outskirts of Shibuya. I was surprised when shortly into my walk the noises of the bustling metropolis seemed to have vanished: I had stepped into a different city. Suddenly I was walking in small neighborhoods that encompassed a mix of functions: single family homes and low-rise apartment buildings of two to six stories, schools, small neighborhood parks, and convenience stores all within walking distance. Planters and bollards mark the edges of pedestrian-only streets whose surfaces are covered with kid-friendly rubber material. How is this one of the densest and busiest cities in the world when you could walk a few blocks from a major business and entertainment district and seem to have stepped into a quiet semi-suburban neighborhood? Unfortunately, corporate-led urban developments are catching up in Tokyo and are beginning to change its urban layout that had survived a multitude of fires and wars. Will Tokyo’s unique urban qualities emerge again after the dust settles from the accelerating market-driven developments?

Figure 6. Ameyoko shopping district, Tokyo

Figure 7. 2k540 Aki-Oka Artisan, shopping street under the JR railway tracks, Tokyo

Figure 8. Businesses and shops under the JR railway tracks, Tokyo

Figure 9. Koenji Pal shopping street, Tokyo

Figure 10. A river that was paved over in 1974 flows under the Kuhonbutsu promenade in Tokyo

Figure 11. A typical mix of housing types in one of Shinjuku neighborhoods viewed from the Yayoi Kusama Museum, Tokyo

Figures 11–19. Eclectic mix of styles, scales and functions in Tokyo’s neighborhoods.

Figures 20–25. Pedestrian-only streets in Tokyo’s residential neighborhoods not too far from Shinjuku’s urban core

Figure 26. Infill development in progress in Tokyo

References

1 Davis, Mike. Dead Cities and Other Tales. New Press, 2004.

2 Ibid.

3 Sorensen André. The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge, 2006.

4 Ibid.

5 Hein, Carola. “Resilient Tokyo: Disaster and Transformation in the Japanese City.” Essay. In The Resilient City How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster, edited by Lawrence J. Vale and Thomas J. Campanella. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

6 Ibid.

7 Schencking, J. Charles. The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

8 Sorensen André. The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge, 2006.

9 Hein, Carola. “Resilient Tokyo: Disaster and Transformation in the Japanese City.” Essay. In The Resilient City How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster, edited by Lawrence J. Vale and Thomas J. Campanella. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

10 Ibid.

11 Sorensen André. The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge, 2006.

12 Ibid.

13 Hein, Carola. “Resilient Tokyo: Disaster and Transformation in the Japanese City.” Essay. In The Resilient City How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster, edited by Lawrence J. Vale and Thomas J. Campanella. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

14 Ibid.

15 Sorensen André. The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge, 2006.

16 Hein, Carola. “Resilient Tokyo: Disaster and Transformation in the Japanese City.” Essay. In The Resilient City How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster, edited by Lawrence J. Vale and Thomas J. Campanella. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top