-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

From Local to Global: Interpreting the Golden Arch in Panama City

Annie Schentag is a 2023 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Of all the incredible buildings in Panama City, it was actually a McDonald’s that surprised me the most. It certainly was not on my itinerary. In my first week on the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, those golden arches were the last thing I wanted to see. This adventure was meant to put me at the doorstep of ‘true’ Panamanian architecture, a mythical local landscape far beyond American influence. I had not anticipated that this particular McDonald’s would be an excellent place to study the architecture of American imperialism.

Figure 1: McDonald’s adjacent to the Administration Building in Balboa, Panama City

Figure 2: McDonald’s located inside former Balboa train station

Positioned in direct contrast to the Panama Canal Administration Building in the former Canal Zone, this fast-food nuisance tells a nuanced story of international relations between America and Panama during the twentieth century. Situated at the edge of the town of Balboa in the former Canal Zone, this McDonald’s is located in an area that still conveys strong historic associations with twentieth-century American occupation of Panama. About 10 miles wide and 50 miles long spanning the width and length of the Panama Canal, the Canal Zone was created as part of the 1903 Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty. Written in English by the United States, this treaty declared Panama’s independence from Colombia. In order to protect American interests and investments in constructing the canal, the treaty also included a major clause that designated the Canal Zone land for American use as if it were their own sovereign land. This essentially created a strip of American land within the country of Panama, where generations of canal workers, military personnel, and their families lived as American citizens until it was officially given back to Panama on December 31, 1999.1

The architecture of the Canal Zone that remains today was largely built by and for Americans, with former military bases, residences, schools, and a cemetery attesting to this near-century of occupation. Commercial buildings and restaurants there once catered to American families, providing a strange sort of whiplash of American architecture slicing across Panama. Travel writer Paul Theroux described the Canal Zone as a “company town, simultaneously comprised of a military base dressed up like the suburbs, a government department, and colonialism in its purest form.”2 The former refers to the Ciudad Del Saber, a suburban style community that adaptively reused the Clayton military base used by the United States forces during the early twentieth century and during the U.S. Invasion of Panama City in 1989. Occupied mostly by Panamanians today, the Ciudad Del Saber is now a cushy residential area with one of the city’s best schools today. It even has a McDonald’s nearby.

Figure 3: Ciudad del Saber, in the former U.S. Clayton military base

The town of Balboa was founded as the administrative capital of the Canal Zone in the early twentieth century. It was carefully planned and designed by architect Austin Lord from 1912 to 1914 to serve as the administrative center for the construction and operation of the Panama Canal by the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC). Richard Guy Wilson, among the first architectural historians to study the Canal Zone as American imperialistic architecture, compared Balboa to the National Mall from the McMillan Plan for Washington, DC, and the Court of Honor at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. In short, he stated, “it personifies power.”3

Figure 4: Administration Building at Balboa

Utilizing City Beautiful principles, Balboa is oriented with the Administration Building at the top of Lone Tree Hill and the Prado lined with tidy rows of palm trees on a broad grass median below. The positioning of streets and buildings reinforces a strong axiality that is central to the plan. Smaller, two-story office buildings line the boulevard within constant view of the authoritatively placed Administration Building at the top of the hill. Since the territory was turned over to Panama in December 1999, these buildings are now occupied by the Panama Canal Authority, still serving an administrative function overseeing canal operations today. Ancon Hill looms in the distance, with the national flag of Panama as a reminder of the successful struggle for Panamanian sovereignty.

Figure 5: View of Goethals’ monument and Prado from Administration Building

Figure 6: Looking along Prado towards smaller administration buildings

The Administration Building itself is a grand sight, an E-shaped steel-framed concrete building that faces in two directions. Designed in 1912 to house the ICC, the building set the standard for future construction in the Canal Zone, with a red tiled roof and a blend of Spanish and Italian Renaissance Revival style details. A 1954 monument to the engineer George W. Goethals was situated at the intersection of the Prado and the base of the steps leading to the imposing Administration Building. Together, the Administration Building, monument, and boulevard lined with smaller offices presented a clear sense of design intentions to convey American organization and power. Always wary of that kind of architecturally-imposed authority, I took the requisite photos, marveled at the pristinely preserved building amidst the 90-degree heat, then politely asked if we could visit the McDonald’s on the other side of the hill.

This was not just any McDonald’s. It was located inside a former railroad station building, a stop on the railroad that ran between Colon and Balboa since the 1850s. Originally built by an American company to accommodate the increased demand of travelers and shipments going to and from the California Gold Rush, the rail lines essentially formed the first complete path across the Panamanian isthmus and the first transcontinental railroad in the world. This route later inspired the route of the Panama Canal, although this later required some alterations to these lines in a few places. This particular station was constructed as the Balboa stop, an early twentieth-century American addition to the passenger rail service that still runs across a portion of the isthmus for cruise ship passengers today.

Figure 7: View of McDonald’s central entrance and railroad platform

Figure 8: Original rail tracks and sign for Panama located at the edge of the drive-through

It is the kind of relatively modest train station that you might see at a whistle stop in the American Midwest or in the smaller stations of the Northeast. The one-story brick and concrete building has a red tiled gabled roof, with a wood overhanging roof supported by simple wood brackets to shelter passengers on the raised platform. Quatrefoil windows attest to European stylistic influence at one end of the building, and a fading painted sign for a ‘lavanderia’ (laundry) attests to previous other uses at the rear. A glass box framed by thick square concrete piers has been expanded and enclosed from the original entrance to house the McDonald's. Any alterations that have been made are relatively modest and do not detract from a clear understanding of the building as a former train station. If there were any doubt about the original function, the train tracks are still present. They lead directly up to the drive through before they are stopped at the asphalt paving, where a former ticket booth became a service window, demonstrating changes in transportation over time.

Figure 9: Drive-through window along original platform

Our driver, Levy, was clearly confused as to why I would want to leave the monumental buildings up the hill to take photographs of the McDonald’s down the road instead. My Zonian tour guide, Tereza Harp, was excited that I was excited about it, however. She had fond memories of eating there in the late 1980s. “You have to understand,” she shared, “when I was a little girl, there was no fast food in Panama. So the only place you could go to get fast food was the Canal Zone area. That McDonald’s was the first ever in Panama, it was a special treat.” To her it was a childhood symbol of modernity, a destination for the shiny food Americans can buy with gasoline as they rush about their busy, comfortable lives. I bought the most forgettable fries in order to take photos inside.

Inside, well, it looks mostly like a late 1980's McDonald’s in America. An apathetic teenager at the counter served the same fried food in American currency, since Panama still uses the U.S. Dollar as currency. Linoleum tiles, acoustic drop ceilings, sticky cushion benches, and fixed glass pane windows characterized the space. Somehow this was even more disorienting, as if I had teleported or time traveled to Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1985 rather than come all this way to Panama City in 2023. In a manner similar to McDonald’s everywhere, American influence left a trail of breadcrumbs and French fries behind, even before they officially turned over the Canal Zone to Panama in 1999. No one wanted to help me eat any of the fries.

There is no greater emblem of American influence in Panama than that particular McDonald’s. And conversely, there is perhaps no greater example of Panamanian adaptation than the reuse of an American-built train station to become the country’s first major fast-food destination. American influence is omnipresent in Panama, but that McDonald’s is the first place where I could begin to see these intertwined histories manifested in architecture.

I did not learn any of this history in school. Despite receiving an excellent American education in a college-preparatory high school, high-ranking private college, and an Ivy League Ph.D., I am ashamed that I did not learn anything substantial about the Canal Zone. At home in Buffalo, I live only a few blocks away from the site where Theodore Roosevelt was inaugurated as U.S. President, after U.S. President McKinley was shot for his involvement in the Spanish American War at the Pan-American Exposition down the road. There was no mention of American involvement in treaties, territories, and displacement, only the glory of the Panama Canal itself. The 1989 U.S. Invasion to capture Manuel Antonio Noriega is only a very vague memory to me as I was four at the time. I do not remember hearing of the final days of America leaving Panama in 1999 amidst the more popular media coverage of the impending Y2K phenomenon that December. Even as a historian of the Erie Canal, the Panama Canal and Canal Zone very rarely is mentioned in my academic circles. My partner, who majored in International Studies and is an immigration lawyer, did not learn anything of these treaties or the Canal Zone either. So, I feel only slightly less embarrassed at my lack of knowledge on the subject prior to visiting Panama.

I suspect some of this ignorance is due to generational differences in media exposure to current events and some due to educational specializations. Regardless, it illustrates the absence of nuanced conversation in American higher education about American foreign policy and architecture in Panama. I willingly acknowledge that I am new to these subjects—Panamanian history and American Imperialism in Panama—but I suspect I am amongst a large group of younger Americans who know very little about this. I am only beginning to learn the many complexities of these stories through research, readings, and conversations, but I can already tell you these absences manifest in the tourist industry in Panama in a few distinct ways.

I feel a strong affinity for places that emerged as shipping and transport hubs, so it was an obvious choice for me to begin my itinerary in Panama City. As a historian of Buffalo, I could not ignore the similarities between Panama City and my own city. In Buffalo, ahem, we also have an important canal. With that canal came industrial innovations, growth and wealth, diverse racial and ethnic communities, a flourishing of arts and culture, and architecture that still embraces and expresses those origins. These cities are clearly quite different, with very different historic and contemporary contexts. Regardless, every time a tour, exhibition, or conversation in Panama City celebrated those aspects it felt like a shared celebration for my city as well. In acknowledging that, I can feel a tectonic shift beneath the surface of my own Buffalo-focused work. I will be bringing home a lot of lessons I am still learning about heritage planning in the context of canal towns, from Panama City, in particular.

Every tour and museum tells a different story of the Panama Canal, depending on the intended audience. Like historiography, heritage tourism practices reveal the creative processes of remembering and forgetting. The tourism industry in Panama faces a major challenge that many ex-colonial places do: how to integrate colonial heritage with a reinterpretation of both Indigenous and modern history.

Figure 10: Observation platform at the Miraflores Visitor Center

Figure 11: Posterboard for IMAX movie at the Miraflores Visitor Center

The story of the Panama Canal is told to American tourists with great sensation in Panama City. I took two such tours, which each went to different ends of the canal. Tours like those at Miraflores and Agua Clara Visitors Centers emphasize the difficult environmental conditions of the canal’s construction, the marvel of its complex engineering, and its commercial benefits in a global economic system. A 40-minute IMAX movie at Miraflores boasts this in 3D, where Morgan Freeman narrates a rapid transition from Indigenous canoes heading down the Chagres River through the apparently linear path of western progress towards a sophisticated technological system that shapes global shipping networks. At the locks, auditorium style seating provides a view of the canal in action, with massive cargo ships passing through slowly as every step is described on a megaphone. This emphasis on the canal as a feat of engineering is certainly warranted—it is indeed a marvel. But it also conceals many of the social aspects of its history, as if by design.

The Museo de Canal (Panama Canal Museum) tells a different story, aimed towards a broader audience of Panamanians, Zonians, and foreign tourists. The building itself embodies the many stages of Panama City’s history that the exhibitions discuss inside. Constructed in 1874 as a hotel, it became the head office of the French canal company. In the early 1900s it was the headquarters of the U.S. ICC, until that same organization moved into the newly constructed Administration Building in Balboa in 1912. It served as a post office from that time onwards until 1997, when it became the Museo del Canal. Like many buildings in Panama City, the building’s significance occurs in many layers of multiple nationalities and historic relationships to the canal.

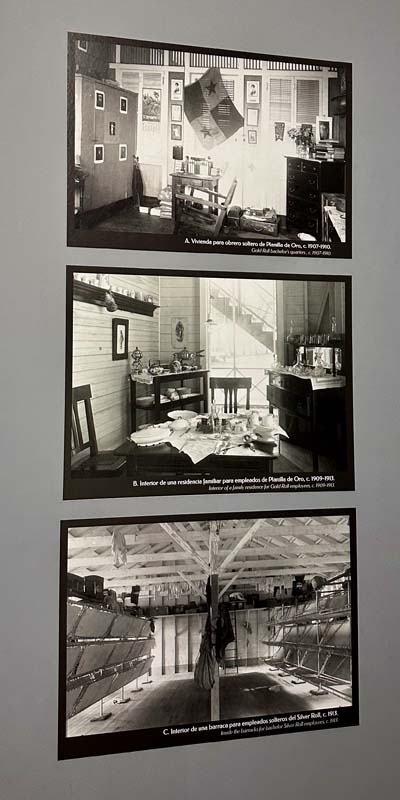

This museum was about an entirely different canal, one experienced by diverse groups of people in different ways over time. It provided primarily a social history: one that empathized with the workers of the canal, illustrated the disparity of wealth in the built environment, and took pride in the great diversity of races and cultures that came to Panama to work on the canal. Several panels and videos were devoted to discussing the Gold and Silver payroll system for workers on the canal, where white Americans were paid in gold and the rest of the workers from the West Indies, China, and beyond were paid in silver. This racially segregated payroll system was also reflected in the built environment of worker housing at the time, where gold-level housing featured grander buildings with window screens, with better educational and entertainment facilities. Silver housing resembled barracks, with fewer amenities, smaller spaces, and substandard social and educational facilities. This type of racial segregation is obviously familiar to Americans, a lamentable transplant of national practices to Panama at the time. This museum was the first and only major place that I encountered that discussion. There was not a megaphone or IMAX in sight.

Figure 12: Photographs illustrating differences between Gold and Silver architectural conditions at the Museo del Canal

There is yet another major story missing from many tours and exhibitions of the Panama Canal. In 1912, the U.S. ICC took steps towards depopulating several towns along the Chagres River. Located within the Canal Zone according to the 1903 treaty, towns such as Gorgona were forced to relocate once the U.S. determined it would be necessary to flood the area to create Lake Gatun to assist with the operation of the Panama Canal. This town, along with several others along the Chagres River, had thrived as a hub for commercial transport between the oceans even before the railroad was constructed in the 1850s. At a time when slavery still existed in America, the town of Gorgona had a Black mayor who oversaw a substantial community. Once the population was forced to relocate in 1912, the town was flooded.4 I took a boat tour across Lake Gatun, which pointed out several monkeys and birds but never mentioned that we were floating above entire towns that were destroyed to construct the canal in the early twentieth century.

In order to get this perspective on the Canal Zone, I was thrilled to meet with Panamanian historian Marixa Lasso while in Panama City. Dr. Lasso’s book, Erased: The Untold Story of the Panama Canal (2019), reveals and analyzes the often untold stories of these former towns along the Chagres River. Her book was deeply influential to me before I traveled to Panama, and even more so now. We sat in a café in Casco Viejo, where our coffees sweat almost as much as I did. When I asked her, with doe-eyed optimism, if there was anything left at all to see of these former towns, she said there was only one part of one church wall. That’s it. One part of one wall of one building of one town, all that is left of several towns that were all dismantled and flooded.

A few months ago, I had never even heard of these communities. Now, I was deflated to hear there was nothing substantial enough left to visit. I cannot even imagine how the descendants of those populations must feel. There is no permanent exhibition to address this, yet. After serving as tenured associate professor at Case Western Reserve University for many years, Lasso returned to Panama City to establish a research center for Panamanian heritage. In an effort to connect her expertise with local and national heritage efforts, she is organizing guest lectures, consulting on exhibitions, and creating a center for researching Panamanian history from multiple perspectives. There may only be a few stones left, but Lasso’s efforts aim to leave none unturned.

There are juxtapositions in Panama City everywhere: ones that complicate traditional binaries between old and new, east and west, nature and industry, invention and tradition, local and global. Every view offers new lessons in harmonious contrasts and multifaceted memories.

Figure 13: View of downtown Panama City from Casco Viejo

1 For more on the complexities of this controversial treaty and notions of sovereignty, see Katherine A. Zien, Sovereign Acts: Performing Race, Space, and Belonging in Panama and the Canal Zone (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017).

2 Paul Theroux, The Old Patagonian Express (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1979), 204.

3 Richard Guy Wilson, "Imperial American Identity at the Panama Canal,” Modulus (1981), 26.

4 Marixa Lasso, Erased: The Untold Story of the Panama Canal (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top