-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Composting Crisis into Community

Annie Schentag is a 2023 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Colombian cities can turn trash into treasure. I mean that literally—some of the most inspiring architecture I experienced in Colombia was built on former garbage dumps. In Medellín and Bogotá, major government initiatives have transformed landfills into libraries. Crime zones have become community centers. The least loved places have become the most central to the nation’s urban regeneration. In terms of urban design and public policies, the United States has a lot to learn from this nation. I spent almost a month in Colombia, absorbing every lesson like a sponge that I am still wringing out.

Bogotá’s public libraries inspire grandiose dreams of writing novels on rainy days. There is something moody and intellectual about the city overall, full of turtlenecks and coffee shops and charming fireplace-heated nooks in which to read and write. The libraries scattered across the city manifest this atmosphere in concrete, brick, and wood, each interpreting it in their own way. In an ideal life, I’d spend each week writing from a different library in Bogotá. There are over a dozen of them, constructed across disparate parts of the city as major public spaces.

Intended to serve as community anchors, these libraries not only hold books but also host events, provide free classes, and serve as distribution centers for major public services. Most of these libraries were constructed in the last 10–50 years, and many of them are located in neighborhoods that once had little else to boast about. All of them are architect-designed wonders that feature different utopic visions of literacy as the path towards community and connectivity.

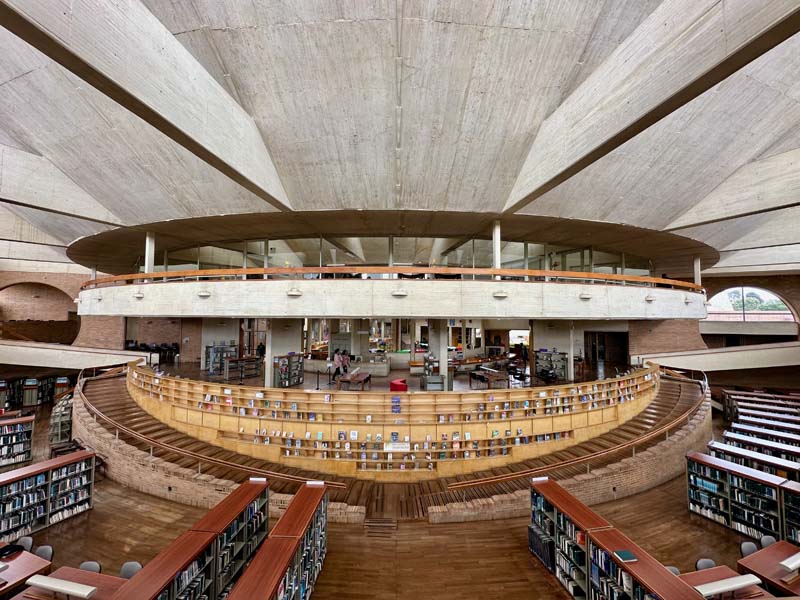

Figure 1. The main reading room at the Virgilio Barco Library in Bogotá.

The Virgilio Barco Library is perhaps one of the better-known examples of Rogelio Salmona’s work in Bogotá. Constructed in 2001 as part of the three mega-library projects across Bogotá, this library is a major destination today, visited by about 60,000 people per month.1 The site posed several challenges to the architect, one of the biggest names in contemporary Colombian architecture. The large triangular site was located on a former dump for construction materials. Rather than constructing a more obvious triangular-shaped building, Salmona designed the library as a snail-shaped edifice in harmonious dialogue with a large, landscaped park. Its plan and orientation require a rambling pace, winding through ramps and promenades inside and out.

Figure 2. Exterior entrance to the Virgilio Barco Library.

Figure 3. A series of stepped water features leads to the main entrance of the Virgilio Barco Library.

Entrance to the Virgilio Barco Library occurs through a series of modern lintels that provides a sense of compression and release, following a pathway of water features that connects to moat-like elements throughout the park. Inside, spirals unfold in graceful curvature. Salmona’s characteristic attention to detail shines through in materials, evident in his own design for a specific wood grain reference in pre-cast concrete and hand-selected glazed bricks in elegant patterns. In addition to the main reading rooms, the three-story building includes an open-air auditorium, multi-purpose gathering spaces, a cafeteria, shops, and exhibition space. At every turn, large pane glass windows frame thoughtfully curated views of the park outside.

Figure 4. A scale model of the Virgilio Barco Library.

Figure 5. Brick, concrete, and wood details grace one of the stairways inside the Virgilio Barco Library.

Figure 6. The Virgilio Barco Library is designed to frame views that connect the inside to the park outside.

Across the city of Bogotá to the southwest, the El Tintal Public Library is a study in diffused lighting and urban rejuvenation. Located—you guessed it—on a former garbage dump, the building was designed to reference its prior use in both topography and design. Designed by architect Daniel Bermudez Samper in 2001, the library was formed from a partial reuse of an abandoned two-story concrete waste management plant on the site. The upper floor is approached directly from the outside via a reused slope formerly used for truck entrances, now absorbed into a large public park surrounding the building.

Figure 7. Exterior view of El Tintal Public Library in Bogotá. A public services fair occurred that day under the tent.

Figure 8. Raised entrance on former truck approach to the El Tintal Public Library.

Figure 9. Second floor lobby accessed from former truck entrance.

In the main reading room, a sequence of lateral lightwells serve both an aesthetic and practical function. The apparent simplicity of these lightwells, which look almost like garbage exhaust ventilation on the exterior, is remarkable. They diffuse the lighting to protect the books inside, but also transform concrete walls into a visual attraction itself. They serve as a graceful reminder that design can transform some of the least-valued places into successful public spaces.

Figure 10. Spiral stair in El Tintal Public Library.

Figure 11. View of reading room with concrete wall skylights visible to the left.

In Medellín, the Moravian Cultural Center hosts a constant array of after-school programs, social events, classes, and recreational facilities. Designed by Rogelio Salmona from 2004 to 2007, the building exhibits his signature use of red brick in a series of asymmetrical curves and angles. Situated atop a former landfill hill alongside a small creek, the building responds to the context of its urban environment rather than dominating it. This building has transformed a former garbage dump into an active hub, providing well-used public space that intentionally keeps at-risk youth away from drug activity by connecting them to one another instead.

Figure 12. The Moravian Cultural Center in Medellín.

Figure 13. View of the Moravian Cultural Center in the context of its site, on a former garbage dump next to a creek.

It was impossible to get a "clean" picture of this building, without people in it—and that’s the point of its design. I could not participate in more traditional forms of architectural photography that typically separate the building from the people using it. Instead, the daily crowds of people surrounding the building demonstrate its success. This building is used in many ways and at many times of day by many people. It is the opposite of a landfill. It cultivates community.

This community center is also just blocks away from the Jardín Botánico, a stunning, free public botanic garden that provides a strong dose of nature within the density of the city. It is connected to the working-class Moravia neighborhood by bike lanes busy with teenagers riding free public bikes to connect to the metro, the planetarium, a science museum, and several major public squares. On a Friday afternoon, each of these places were filled with local residents of all ages- walking, biking, eating, talking, playing music, doing whatever people do on a Friday afternoon. This neighborhood was alive, vivid, lived-in like a familiar shoe.

Figure 14. The Orquideorama at the Jardín Botánico in Medellín.

Figure 15. Public space at the Parque de Deseos in Medellín.

The designs for these buildings and spaces are gorgeous, but what is even more incredible to me is that people use these spaces, daily. In urban design, that often seems to be the biggest challenge, the x-factor that we can’t quite figure out. How do we attract people to public spaces and make sure they will adopt these places as their own? Medellín has figured out that magic formula.

Changing the Conversation

Public architecture, public spaces, public transportation, and public programming—this has been a major series of interconnected investments aimed to improve quality of life for Colombian residents. Basic human rights and quality of life are clear priorities in the nation’s policies and practices, ranging from affordable housing to public health to socially inclusive legislation. The nation has installed its own fiber-optic network cables to provide free internet access in all public spaces and increased transportation networks to serve the poorest communities.

Figure 16. Colombia’s approach to high design for the common good is evident in examples such as Rogelio Salmona’s Torres del Parque (1968–1970), a public housing tower with elegant, shared spaces and individual balconies in Bogotá.

Colombia is not a silenced state. Both authorities and residents have acknowledged the negative, persistent realities that the country faces as a method of collective improvement. The nation faces the challenge of overcoming a reputation that is no longer a reality in most places. Visiting Colombia, you will not encounter the land of that shall-not-be-named Netflix show and the shall-not-be-named infamous drug lord. His name is so controversial in Medellín, actually, that some tour guides will not say it aloud. Colombian residents do not hide that reality, but they seem more interested in moving forward.

Frankly, I am not interested in discussing Colombia in relation to its violent drug-fueled history. Most people I met were not particularly interested in discussing it either. They acknowledge it as an unfortunate fact, as a frustrating era of unfathomably complex opinions and losses. People do not pretend it never happened. They incorporate it as one major aspect of a far more complex, diverse, and rich national identity. There is so much Colombia to discuss, outside of drugs. They are working hard to change that conversation, and I am happy to follow their lead.

Even as an outsider, a week in Bogotá provided a quick, introductory level education to the major issues faced in the city right now: debates over oil production, legalizing marijuana sales, displaced residents and refugees, sexuality inclusive policies, and femicide. Organized demonstrations occur regularly and generally peacefully in the nation’s capital, typically in major public squares and in front of government buildings. Artful signage with compelling language hangs on official police barricades right in front of military buildings, officially embraced as a form of dialogue for everyone to see even if it is explicitly criticizing the military or government.

Figure 17. The Plaza de Bolivar is a major public space for demonstrations and celebrations in Bogotá.

I learned all of this mostly by simply walking around, being in the city. By viewing visual, performative, and political dialogue, the city makes it easy to learn the discussions at hand and the stakes involved. It is a place in conversation, with each other and with officials and with the city itself. Public spaces such as Plaza de Bolivar serve so many key functions, especially in hosting demonstrations, debates, and celebrations. The nation’s capital does not hide its challenges but instead takes pride in the ability to work them out collectively and publicly. Despite, even because of, all of these challenges and problems, the overwhelming attitude seems to be a sense of pride in urban regeneration. There is a lot to be proud of.

Transformation and Tourism

The Medellín neighborhood of Comuna 13 is an often-cited example of the city’s urban regeneration practices. This community was originally an informal settlement that experienced some of the worst violence during the 1990s and 2000s, but today it is a major destination for learning about Medellín’s transformation.

Figure 18. Comuna 13 is a neighborhood located on steep hills at the edge of Medellín.

Figure 19. Public pathways in Comuna 13, with the central city in the distant valley.

The area’s steep hills and location at the west edge of the city made it a key point for controlling shipment networks. As a result, Comuna 13 was essentially under control of cartels for many years. The area was also physically disconnected from the civic resources in the center city of Medellín, requiring a steep climb along narrow, disconnected paths of stairs for nearly an hour in order to reach major hospitals, schools, and places of employment. Even once Escobar was killed in 1993, Comuna 13 continued to suffer from the lack of basic public resources.

The installation of the cable car system in 2004 and a series of escalators in 2011 proved to be major turning points for Comuna 13. The escalators reduced a difficult climb to a pleasant five-minute ride. Connected by a series of landings, these long escalators provided a free ride up and down the steep hills, covered to protect riders from sun and rain. At the bottom of the hill, one could leave Comuna 13 and ride the cable car into the city, where it connects to the metro to access any major part of Medellín—and along with it, hospitals, schools, markets, and other essential services.

Figure 20. Entrance to one of the public escalators in Comuna 13.

Figure 21. Artwork adorns many surfaces in Comuna 13, with shops accessed by long sets of stairs alongside the escalators.

The city did not build expensive new schools or hospitals in Comuna 13, it instead invested in connecting this community to other communities as a first step. It is a mind-blowing example that provides a major lesson: public transportation can be one of the most effective ways to address and ameliorate poverty, violence, and injustice. In 1991, Comuna 13 was the "murder capital of the world." Thirty years later, it is a major tourist destination on the rise.

I had the privilege of visiting Comuna 13 five years ago in 2018, when only two tours were offered. Visiting again in June 2023, it is clear this community has become a tourist hotspot for many types of national and international visitors. Now there are dozens of tours, a whole street of vendors, Comuna 13 branded t-shirts and hats designed by local artists, and even nightlife that occurs in select locations after dark. The area has clearly embraced tourism as part of its economic regeneration.

Figure 22. View of street at entrance to Comuna 13 in 2018.

Figure 23. Tourists watch a breakdancing demonstration on the same street in 2023.

The ongoing story of Comuna 13 is presented on tours as one of resilience and regeneration, not solely of victimized suffering. Many of these tours are led by former gang members, who established their own tour companies and obtained funding partially as a result of the 2016 peace deal. Just to be clear: that means that the Colombian government funds the telling of these stories and does not control the way they are told. Instead, it provides employment that simultaneously strengthens the local economy and empowers residents to transform and translate their own history.

Bullet holes still dot the sides of buildings in Comuna 13, but they are incorporated into official public murals. Rather than gang-related graffiti, the public art of Comuna 13 is celebrated worldwide. Major competitions occur in order to paint in Comuna 13, with famous names like Chota13 and YesGraff represented alongside those of local residents. These pieces are a major form of storytelling, which attract many tourists on art-specific tours. They are also places of play, expression, and narrative exploration for residents, a part of daily life as it continues to unfold.

Figure 24. A glimpse of daily life in Medellín’s Comuna 13.

Making Connections

Public transportation is a major point of pride in Medellín and Bogotá, and I can see why. They are the cleanest, most efficient, and most affordable systems I have ever experienced. Celebrated as best practices of public transportation worldwide, these systems prioritize the daily needs of the communities they serve. It is a form of urban activism in Colombian cities, installed and used as a means to connect assistance to those who need it most.

The Metro and Tranvia cable car system in Medellín was first constructed in the mid 1990s and expanded in the early 2000s, during a time when the city was experiencing major violence and unrest in the midst of drug trade conflicts. Today it serves the city of about 2.5 million people, connecting the informal settlements on the Andean foothills with the many central neighborhoods in the Aburra Valley for the cost of about 75 cents (USD) per ride.

Figure 25. Typical station on the Medellín Metro system.

Figure 26. The cable car system in Medellín.

In Bogotá, the Transmillenio was first constructed in 2000 and expanded again in 2006, the second system of its kind in the world after Curitiba, Brazil. Essentially operating as a metro in disguise, this Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system has large buses occupy their own lanes with designated stops around the city and into the tall peaks of the Andes for about .70 cents (USD) per ride. Many urban studies have already praised Medellín and Bogotá’s systems for their quick construction, environmentally sensitive technology, effective routes, and socioeconomic impacts.2

Figure 27. The Transmilenio BRT system in Bogotá features separate lanes designated for buses, with specific stations at the center of the street such as this one.

Figure 28. Every Sunday in Bogotá, over 10 miles of streets are closed to vehicular traffic for the Ciclovia for 7 hours. This biking- and pedestrian-centered event has been so successful that it occurs every Sunday in other Colombian cities as well.

What often gets lost in these discussions, however, is the sheer joy of riding these networks. In their routes and signage, they encourage safe and friendly human connections. In Medellín, a voice recording on the overhead speaker periodically reminds everyone to inhale and exhale amidst announcements. Small signs dot the trains, stating "calidad de vida" (quality of life) as a reminder of the motivations behind the Metro.

Commissioned artwork adorns major stations, but the trains remain squeaky clean inside and out. I did not witness a single piece of litter in any train, bus, or station in Colombia. I did not witness nor experience any interactions that were anything less than cordial—no violence, no pickpocketing, no harassment. I felt safe in Colombia, which seemed as important to locals as it did to me. I felt safe because the nation works hard to create a sense of perceived safety and takes great pride in that safety. No one will mess with the Medellín Metro. It is a known and celebrated asset, and it is often the safest place to be.

On Medellín’s Metro and Bogotá’s Transmillenio, I witnessed and experienced numerous acts of kindness that might seem extraordinary in other places. Strangers of disparate socioeconomic backgrounds sharing kind words, sharing seats, sharing food. Just a typical commute that provides the "calidad de vida" that Colombia has earned the hard way and now revels in, every day. It embraces a romance of mundanity that can feel like a privilege after it has not felt like a right for so long. In short, riding public transportation in Medellín and Bogotá felt like a microcosm of how living in cities should feel and can be, at its best.

1 Laura Saenz, “Architecture Classics: Virgilio Barco Library,” Arch Daily (May 17, 2023). Accessed July 2, 2023 at https://www.archdaily.com/1000228/architecture-classics-virgilio-barco-library-rogelio-salmona

2 There are at least dozens of studies by accomplished and emerging scholars on these transit systems. Perhaps the one that has influenced me the most (about Bogota in general) is: Berney, Rachel. Learning from Bogotá: Pedagogical Urbanism and the Reshaping of Public Space. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top