-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

A Year on the Road with my Iraqi Passport Studying War and Reconstruction across the World

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

I started this fellowship wanting to study cities that have experienced war, to learn which of their urban and spatial qualities today are attributed to decisions that were made during the reconstruction years by what was physically rebuilt after the war, or by policies that govern a city’s development and growth. I wanted to understand the irreversible long-term consequences of wars on place-making across different cultures by observing what kind of cities wars produce.

I began with the same question in each city I visited: what was driving the narrative of reconstruction when the war ended? Political ideology? Economic rebirth? A need to break from a difficult past? Opportunities to correct certain problems in the urban environment that were suddenly liberated from constraints of historic preservation?

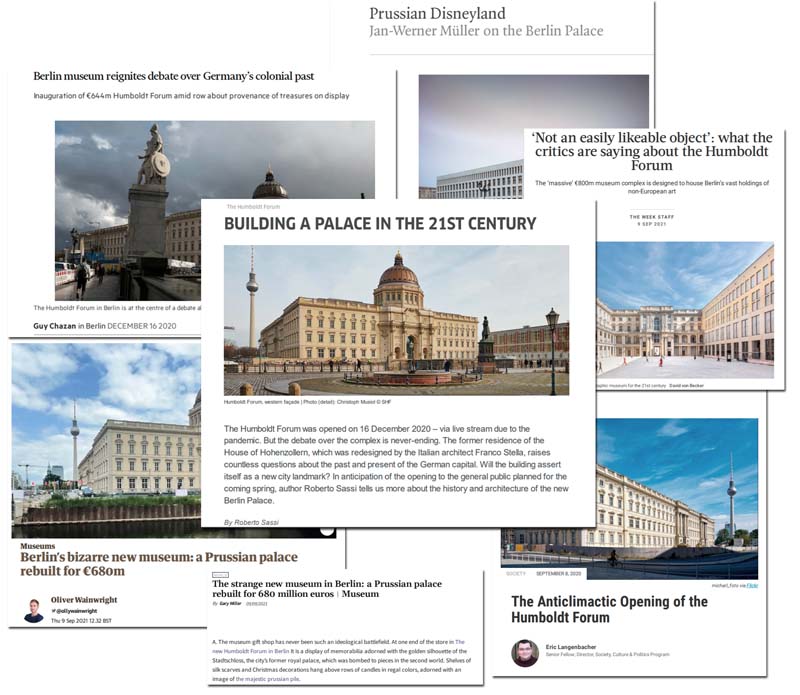

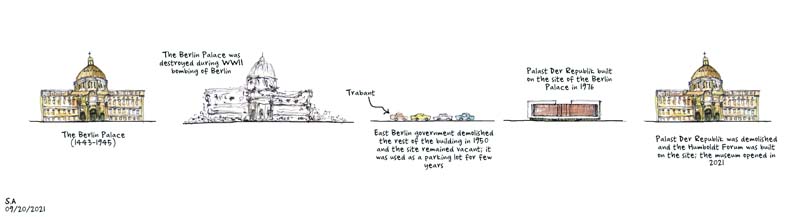

Berlin was the perfect city to begin this research because not only was it destroyed during WWII by allied bombing but for 30 years it was a divided city and the ideological battleground between East and West during the Cold War. Berlin is one of the best examples to observe how architecture could be utilized to express and cement political ideologies when looking at the reconstruction of West and East Berlin side by side. It is also a city that still interrogates the assumptions behind what was rebuilt, neglected or demolished after the war and the end of Nazi Germany, always contending between coming to terms with its tainted past or moving past it. The Humboldt Forum in Berlin is a good example of how the questions and debates of post-war reconstruction can continue for decades, because what is eventually built has the power to tell its own version of history.

Figure 1. A snapshot of recent articles following the opening of the Humboldt Forum

Figure 2. My sketch illustrating the history of the site

The second guiding question for my research was: what replaced destroyed neighborhoods or buildings of historical importance when the war was over? Who had the power to decide what should be built? In Warsaw, the new communist government and the public were determined to rebuild an exact replica of the Old Town after the Germans obliterated it as they fled Poland. For the Polish people, the attack on Warsaw was akin to cultural cleansing and rebuilding a facsimile of the Old Town was a way to preserve a cherished record of Polish history notwithstanding the lack of architectural documentation that was needed to build the demolished quarter.

Figures 3–4. Warsaw’s Old Town

While the unique cultural context of each city produced a different approach to reconstruction, as I went from one place to another, I tried to observe what similarities war-torn cities in their reconstructed states share. Were there universal symptoms that plagued the post-war city that could be learned from and avoided as governments, policymakers, planners, architects, and other actors rush to rebuild cities ravaged by wars in Ukraine or the other lesser covered war-torn cities in Yemen, Syria, and Afghanistan? Early on in my fellowship travel, it became apparent to me that destruction of architectural and cultural heritage by the development-driven approach of a global free-market capitalism, often led by foreign development companies, pose an equal, if not exceeding, threat than wars on the built environment. War-torn cities are especially vulnerable to this type of sweeping, large-scale urban transformations as it is one of the first viable paths towards economic recovery. In addition, the intervention of the international community bringing investment and aid to the post-war city means that decisions of what should be rebuilt are no longer rooted in the needs and desires of the local context. As I observed in Sarajevo, Istanbul, and Seoul, the result of this market-driven reconstruction is an increasing commodification of urban space that produces a standardized global aesthetic of apartment towers and shopping malls, making cities across different cultures and continents look the same.

Figure 5. BBI Centar, a shopping mall in Sarajevo, part of a privately owned development that was built after the war to replace an iconic state-owned department store, Robna kuca Sarajka, that stood on the site since 1975

Figure 6. Sarajevo City Center

Figures 7–8. View of Seoul from Inwangsan Mountain

Seoul is still trying to correct the aggressive government-controlled urban development of the first 30 years after the Korean War. Reconstruction was only a functional means to achieving economic prosperity through accelerated industrialization, and frenzied building was led by industrial conglomerates that controlled South Korea’s economy. However, when the definitions of what it means to be a global city shifted in the early 2000s to encompass cultural, environmental, and historical characteristics of a city, Seoul began to shift its attention to reviving its old palaces and historical quarters that until then were neglected and in ruins. Until today, Seoul continues to struggle to rebrand its image from the efficient industrial city of high-rise towers that was born after the war to a cultural destination. Seoul is a good example of the risks of the early decisions of reconstruction that become lodged in the urban form and almost impossible to undo the losses to the historical and cultural identity of the city.

Sarajevo’s reconstruction after the Bosnian War in 1995 is a cautionary tale of how a post-war city could be reshaped by external actors such as international aid organizations and foreign governments who, as donors, often set the priorities of reconstruction for the city. For Sarajevo, not only did these interventions ignore real needs like the importance of recovering sites of cultural significance that brought different groups of people together, but the flow of foreign capital followed along political and ethnic lines, exacerbating the divisions between Bosniaks and Serbs in Sarajevo.

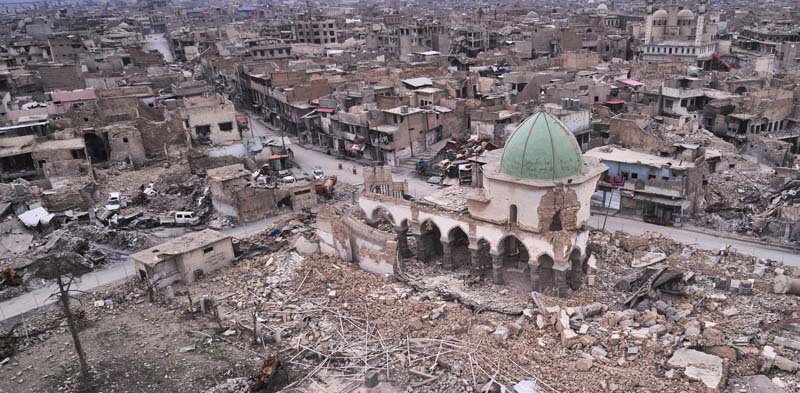

A paternalistic approach to reconstruction that is disengaged from the local context is not uncommon within the context of international aid in post-conflict cities. In 2020, UNESCO, with the support of the UAE, announced a competition for the reconstruction of Al-Nouri Mosque in Mosul, in my home country of Iraq. The mosque was damaged in 2017 by ISIS. The winning entry by an Egyptian team caused an outcry from Iraqi architects and residents of Mosul who saw the design architecturally divorced from the vernacular of Mosul and closely resembling in materiality and language the architecture of the UAE, who is funding the project. The alien design is currently under construction despite the controversy and pleading from renowned Iraqi architects like Ihsan Fethi.

Figures 9–10. A ruined Al-Nouri Mosque in Mosul (Image from archdaily.com)

Figure 11. The winning competition entry to reconstruct Al-Nouri Mosque (Image from https://news.un.org)

When I came across the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, I had for a long time this research idea to explore how the numerous wars in Iraq shaped my hometown of Baghdad, including the 2003 war, which I grew up under. It was a topic that I began exploring in some of my research papers in undergraduate and graduate school but couldn’t find a place for within my academic and professional career. I found that when the issue of war and architecture are explored, it is often within the framework of immediate emergency response such as the design of temporary and modular housing to mitigate a refugee crisis. But as someone who had a lived experience of war and who had seen the destruction of my hometown, I understood that rebuilding in such contexts encompassed more abstract notions that related to people’s sense of place and history, considerations that went beyond mere survival. So when I discovered the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, my research fell into place: in order to begin to understand how to rebuild a city, like Baghdad, that had lost so much of its architectural heritage, I had to look elsewhere, at other cities that have been destroyed and rebuilt to learn what their stories of reconstruction could teach us about the challenges and risks in designing for post-war societies.

The most valuable gift of this fellowship was that of time: time spent reading about each city I visited; time spent walking, sketching, writing, and thinking. Even time spent processing some of my own experience of war in relation to the history of wars and conflicts I was studying. Spending a month on average in each city allowed me to observe not only what was destroyed and rebuilt but the quality of the urban experience in terms of access to public transport, walkability, public space, parks, and cultural experiences. This had added a valuable dimension to my research that I had not anticipated. The transformative last year and a half of travel and exploration showed me that research alone is not enough to understand and conclude what a building or a city is like. I am very grateful to the Society of Architectural Historians for granting me the opportunity to launch this research project, which will continue to be part of my future work beyond this fellowship.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top