-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

On Improvement: Waste, Wheat and White Possession

Sep 13, 2024

by

Jasper Ludewig, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architectural historian Jasper Ludewig is a lecturer in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at the University of Newcastle in Australia. He earned his PhD from the Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning at the University of Sydney in 2020 and his Bachelor of Design in architecture from the University of Sydney in 2012. He currently serves as associate editor of Architectural Theory Review.

Through the 2023 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Dr. Ludewig hopes to gain insight into the landscapes, structures and processes implicated in the history of resource subimperialism throughout the nineteenth-century South Pacific. He will focus on the period between 1880 and 1919 when British, German, Anglo-German and Anglo-French consortia extracted rock phosphate from hundreds of islands for use as an industrial fertilizer. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

________________________________________________________________________________________

The H. Allen Brooks Fellowship afforded me many invaluable things: the time to immerse myself in new ideas; an invitation to experiment with novel (for me) forms of writing; the resources required to explore unfamiliar and otherwise inaccessible places; and an engaged audience with whom to share early work. I leave my tenure as fellow with a greater appreciation of the immediacy of fieldwork and its importance in ground-truthing the historical record. I leave with an expanded understanding of the architectures of Australian empire. And I leave with lived experience of the disaggregated geographies of phosphate imperialism. In no uncertain terms, this fellowship—encompassing archival finds, spectacular land- and waterscapes and near-death experiences—has been transformative for me as a scholar. While my colleagues in other disciplines continue to ponder how travelling to islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans constitutes research, I am left with questions and projects that will continue to preoccupy me for many years to come.

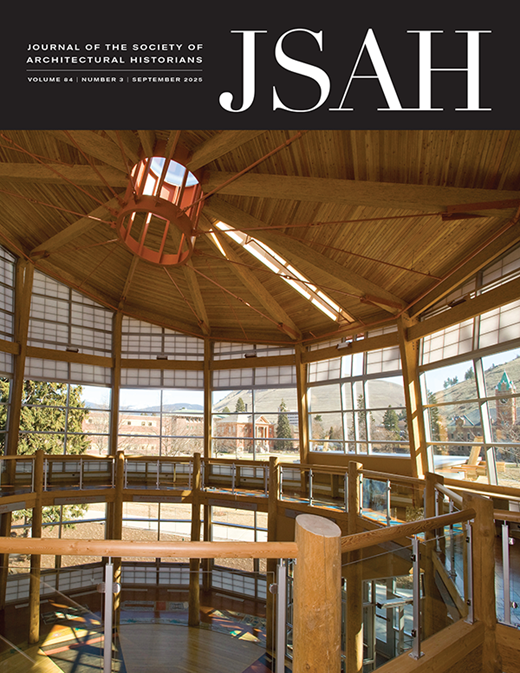

Fig. 1 - Department of External Affairs, 125,000 Bags of Wheat Awaiting Shipment, South Australia, Under the Southern Cross: Glimpses of Australia, 1908.

Here, I seek to recapitulate the initial ambition of my fellowship project: to reconstruct the historical infrastructural network of phosphate imperialism in the Indo-Pacific and to read this network against the forms of political order, organizational governance and dispossession with which this network was always entangled. As explored in my previous reports, these objectives ultimately led me from the east coast of Australia to England, Germany, Nauru, Christmas Island and Palau. What emerged is a complex picture of empire in which various, often overlapping forms of public and private power cooperated in the pursuit of mining rights on remote islands to serve the escalating needs of chemical manufacturing throughout the industrialized world. More specifically, my travels followed a kind of triple displacement in which (1) the extraction of phosphorous from the Indo-Pacific (2) consolidated European colonialism in the region as an extension of Australia’s ballooning wheat production, which in turn (3) entrenched settler colonial dispossession of Indigenous land throughout the continent’s grain growing regions (figure 1). By stitching together field and furrow, experimental agricultural station, port and railway, chemical manufacturing and offshore mining, my travels aimed to capture these displacements at work, approaching them as fundamental processes in the settler colonial enclosure of political territory (figure 2).

Fig. 2 - Overlooking the former workers’ housing at Location on Nauru.

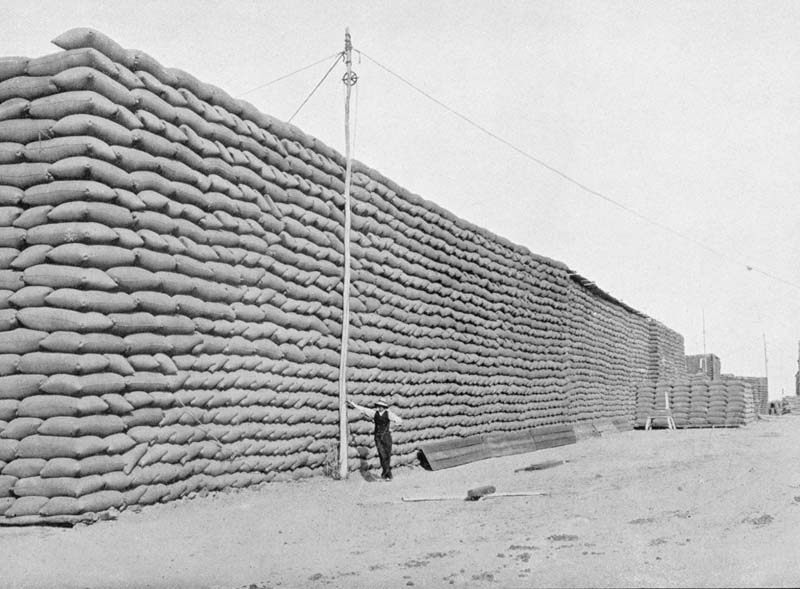

Improving the fertility of land both underpinned the ideology of a productive, well-ordered society and was a key rationale in and justification for Indigenous dispossession according to the doctrine of terra nullius. As the urban geographer Libby Porter has argued, modern planning law remains grounded in notions of “exclusivity, sovereignty, property and correct land use” in which “improvement, cultivation and civilisation” are both a moral right and a duty within the project of the colony.1 Experimental agricultural stations, tasked with adapting European techniques of improvement to Australian conditions, were established throughout the colonies in the nineteenth century. My travels took me to one such station in northern Victoria—Dookie Agricultural College—where aspiring farmers were trained in all practical, scientific and administrative aspects of modern agronomy (figure 3). As the experiments conducted at Dookie revealed, nothing came close to the chemical fertilizer superphosphate for stimulating plant growth in Australia’s phosphorous-deficient soils. Its uptake at the turn of the twentieth century was dramatic and pervasive: state-subsidized railways connected phosphate works on the coast to burgeoning agricultural districts inland where one shipment of rock phosphate could provide 1000 farms with their annual supply of fertilizer; state banks offered attractive house and land packages, enabling colonists to immediately acquire grain, fertilizer and agricultural equipment before commencing their repayments; mallee country and sclerophyll forest were divided into selections, ringbarked and burnt, raked and grubbed, stripped and ripped, electrically blasted, graded and canalized, before being injected with grain dowsed in chemical fertilizer.

Fig. 3 – Dookie Agricultural College, c.1898.

In just two decades, the 50,000 hectares of land cleared and transformed into wheat fields in Western Australia by 1890 had ballooned to 2.1 million—an area the size of Wales—matched by similar increases in the southern colonies. Driving through these regions today, the rhythmic pattern of the raked earth demarcates the intimate scale at which these largescale environmental transformations were ultimately performed (figure 4). By the early twentieth century, according to agricultural commentators and politicians, Australia had become a so-called “super state”—an avowedly white and virile political community, which had overcome the natural deficiency of Indigenous soils through systematic improvement and coordinated chemical engineering. 2 The wheat industry made Australia in the early twentieth century just as superphosphate made the wheat industry.

Fig. 4 – Wheat field in the Wimmera, Victoria.

Leaving Australia, my travels brought two interdependent trajectories into view: on the one hand, an intensive process of chemically transforming unceded Indigenous land to better support the reliable growth of a variety of imported cereal grasses—wheat—within a settler colonial political economy. And, on the other, an extensive process of securing the requisite raw material—rock phosphate—from a handful of islands in the Indo-Pacific upon which that growth and subsequently that political economy depended. This is referred to by Brett Clark and John Bellamy Foster as the “environmental overdraft” in which industrialized states imperialistically draw on ecologies and labor elsewhere to fuel “the social metabolic order” of the particular capitalisms to which their state formation is tied. 3

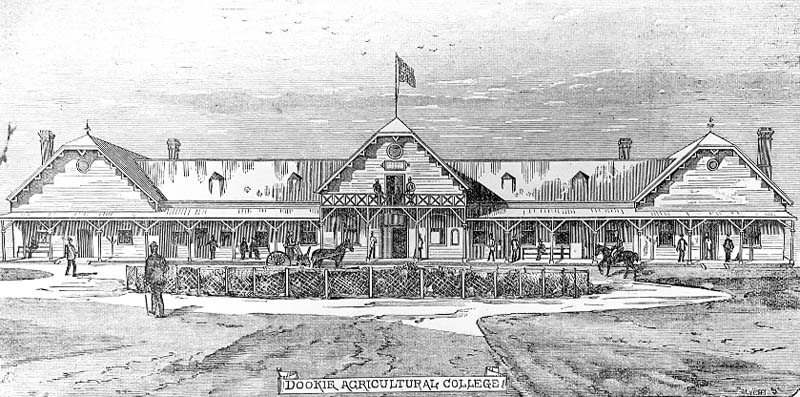

The technical dimensions of this overdraft varied from island to island and developed significantly over the course of the twentieth century, but always involved shoveling, picking, scraping, drilling, hammering or blasting the rock phosphate from the limestone that formed the geological structure of each island. Today, scarified and disturbed land indicates the former mining sites, torn into tropical forests on each of the islands. On Nauru, the central plateau is uninhabitable, having been dug back to jagged pinnacles that now rise from its reengineered surface (figure 5). On Christmas Island, geometrical patches of rock and earth continue to be exposed deep within the island’s national park (figure 6). On Angaur in Palau, a thirty-meter mining pit, once known as Doresha, has penetrated the island’s water table. Locomotives, narrow-gauge tramways and aerial cableways conveyed the mined rock from these sites to the crushing and drying facilities at the ports where the phosphate was finally loaded directly onto steamers via belt conveyors on pivoting steel cantilevers, arriving at Australia’s fertilizer manufacturers around two weeks later. Here, the rock was crushed further and mixed with sulphuric acid before being bagged and loaded for distribution (figure 7).

Fig. 5 – The landscape phosphate mining has left beside at Topside, Nauru.

Fig. 6 – Mining continues within the Christmas Island National Park.

Fig. 7 – Mt Lyell Chemical Works, Yarraville, Melbourne, c.1920.

These processes were coordinated on each island by imperial technocracies in miniature, complete with their own public works departments. Countless structural, hydraulic and mining engineers, architects and naval architects, boilermakers and carpenters, company executives and imperial administrators lived in racially segregated company settlements, administering remote industrial mining ventures for close to a century and managing a vast labor force. Conditions were overwhelmingly horrific, as captured in the extreme discrepancies in mortality rates between the European managers and the Japanese, Chinese, Malay and Pacific Islander laborers indentured to each island. Protests against unsafe, unhealthy and inhumane working conditions were, over time, used as justification for increased surveillance and policing of the workforce. This further reified regional hierarchies between a generalized wage labor force in Australia’s urban-industrial centers and primary industries, and the indentured, often incarcerated labor deployed in their service on the phosphate frontier. 4

As Roger C. Thompson observed in his study of nineteenth-century imperialist attitudes in Australia, the Indo-Pacific ambitions of Australian companies and politicians were instrumental in shaping the final limits of Greater British imperialism in the region, demonstrating the “primacy of peripheral forces for political expansion in the growth of the British Empire.” 5 Those involved in the Indo-Pacific rock phosphate industry thus joined a wider cast of actors pursuing what the Victorian Premier Graham Berry, in 1877, had called “a kind of Monroe Doctrine” under which “all the islands in this part of the world should be held by the Anglo Saxon race.” 6 The vast copra reserves amassed by Lever’s Pacific Plantations throughout the British Solomon Islands (Lever was also a major investor in the Pacific Phosphate Company, which worked Nauru and Banaba before World War One); the sugar infrastructure constructed in Fiji by the Colonial Sugar Refining Company; Burns, Philp & Co.’s settlement scheme for cotton plantations in the New Hebrides; the web of mission stations developed there by the Presbyterian Church of Victoria; in addition to the myriad Australian trading stations, properties, wharves and settlements—these were the collective physical evidence that accompanied calls for imperial protection and visions for white possession of the Indo-Pacific (figures 8 – 10). As remarked in the Adelaide Advertiser following federation in 1901:

Now, however, that we have the machinery for bringing the concentrated opinion of Australia to bear upon matters affecting our continental interests, we may expect to find attention once again turned towards the numberless islands that dot the huge watery waste around us, and which—whatever allegiance they may now own—we still regard as [...] preordained, at however remote a date, to be our heritage. 7

Fig. 8 – Advertisement from c.1920 for Lever Brothers Sunlight soap, manufactured in Balmain, Sydney using copra acquired by Lever’s Pacific Plantations in the British Solomon Islands.

Fig. 9 – The Colonial Sugar Refining Company’s sugar mill in Labasa, Fiji, 1924. CSR Archive, Australian National University, 171-58.

Fig. 10 – Burns, Philp & Co.’s store in Vila, New Hebrides, 1911. Australian National University Archives, N115-625.

Australia’s empire never took the heightened forms of direct colonization, annexation or invasion of territory inferred by the Advertiser; rather, it was amassed gradually through the increasing bureaucratization of political authority on islands of value to its economic development. Phosphate is just one vector in this broader history, underpinned by what Priya Chako describes as “layers of dispossession,” 8 whereby attempts to develop an agricultural economy to secure white possession of stolen Aboriginal land “at home” in the Australian colonies depended upon extraterritorial dispossession throughout the Indo-Pacific, collapsing neat geopolitical distinctions between Australia and its offshore resource frontiers, and between public and private power.

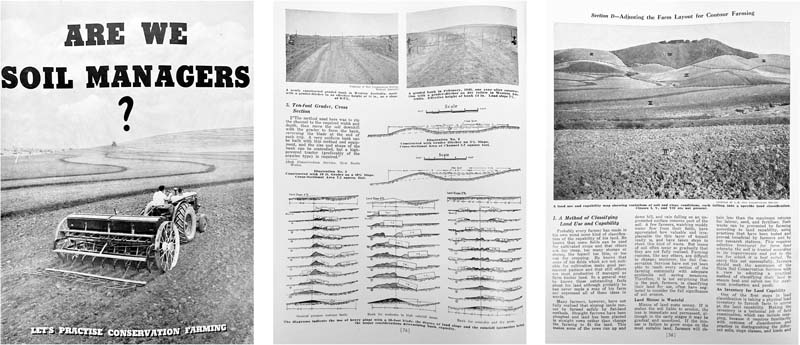

Fig. 11 – Excerpts from Are We Soil Managers?, a trade magazine published by the International Harvester Company, c.1955.

One implication is that the spaces of Australian agriculture—those through which I traveled, and which recur throughout the distributed archive of the Indo-Pacific phosphate industry—must also be understood as sites of Australian imperialism. The two cannot, in fact, be separated. By the mid-twentieth century, at the peak of Australia’s rock phosphate consumption, improvement was characterized as much by dramatic increases in land clearing, mechanization, genetic modification and the total chemicalization of farming, as the almost total decimation of remote phosphate islands. As it had been since British invasion of the continent in the late eighteenth century, soil remained the medium for envisaging, organizing and sustaining the settler colony. According to one trade magazine (figure 11):

We should manage every last particle of our soil as we manage our bank account. ...We should treat personally and individually this responsibility as a moral obligation. [...] Soil erosion wastes fertility and soil. Wasted soil means less nutritious food. When the land suffers and is wasted, both landowners and city people suffer, eventuating in wasted lives. 9

Waste, as improvement’s inverse, was not only antithetical to modernity and national progress, but was also a moral problem deeply rooted in colonial understandings of land, property and social reproduction. As the historical geographies of superphosphate ultimately clarify, white supremacy in Australia was contingent on Australian imperialism in its region and vice versa; Australian exploits in the Indo-Pacific were supposedly legitimized by its sovereign independence and historical trajectory as a white ethnostate. These imperial hierarchies continue to structure Australian relations with its regional neighbors today, albeit couched in sanitized notions of a shared past and the so-called “Pacific family,” rather than the white man’s burden and murmurings of manifest destiny. 10 This fellowship has enabled me to attend more closely to the spatial and territorial forms of this history as embodied in the carefully designed buildings and infrastructures of the superphosphate industry (figure 12). As I have attempted to argue, these forms cast the placatory tropes of Australia’s contemporary geopolitics in a different and more glaring light, whereby questions concerning reparations for Australia’s historical overdraft on ecological abundance overseas sit alongside calls to “pay the rent” for the dispossession of traditional owners at home.

Fig. 12 – Remnant phosphate bin on Nauru, built during the period of the British Phosphate Commission.

Whereas it was the process of writing that first brought these various entanglements and displacements into view for me, my travels revealed the extent to which they were already written into the physical landscapes themselves. Travel animates the imagination in ways that conventional forms of scholarship cannot, challenging the convenience of neat historical narratives and complicating the historian’s straightforward appraisals of motive and causality. Navigating this complexity has clarified the critical work historiography performs in making the past available to present concerns. Attempting to do so with nuance, rigor and balance has been extremely challenging, catalyzing much self-doubt along the way. Working through these difficulties requires the time and space to sit with new impressions and to understand their implications for what is supposedly settled knowledge. Being afforded both at once is an immense privilege and I am deeply grateful to the Society of Architectural Historians and the late Professor H. Allen Brooks for their generous support.

[1] Libby Porter, “Dispossession and Terra Nullius: Planning’s Formative Terrain,” in Sue Jackson, Libby Porter and Louise C. Johnson (eds.), Planning in Indigenous Australia: From Imperial Foundations to Postcolonial Futures (London: Routledge, 2018), 61–62.

[2] Derek Byerlee, “The Super State: The Political Economy of Phosphate Fertilizer Use in South Australia, 1880–1940,” Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 62, no. 1 (2021): 99–128.

[3] Brett Clark and John Bellamy Foster, “Ecological Imperialism and the Global Metabolic Rift: Unequal Exchange and the Guano/Nitrates Trade,” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 50, nos. 3-4 (2009): 311-34.

[4] Marion W. Dixon, “Phosphate Rock Frontiers: Nature, Labor, and Imperial States, from 1870 to World War Two,” Critical Historical Studies 8, no. 2 (2021): 271–307.

[5] Roger C. Thompson, Australian Imperialism in the Pacific: The Expansionist Era, 1820–1920 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1980), 220–24.

[6] Quoted in Marilyn Lake, “Colonial Australia and the Asia-Pacific Region,” in Alison Bashford and Stuart Macintyre (eds.), The Cambridge History of Australia, vol. 3, Indigenous and Colonial Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 555.

[7] Quoted in Thompson, Australian Imperialism in the Pacific, 158.

[8] Priya Chako, “Racial Capitalism and Spheres of Influence: Australia Assertions of White Possession in the Pacific,” Political Geography 105 (2023), doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102923.

[9] Unknown, Are We Soil Managers? (Geelong: International Harvester Company of Australia, c.1955), 8.

[10] On the “Pacific family” discourse, see Joanne Wallis, “The Enclosure and Exclusion of Australia’s ‘Pacific Family’,” Political Geography 106 (2023), /doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102935.