-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Modern Pueblo, or the Presence of the Past

Aug 19, 2025

by

Francesca Sisci, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Francesca Sisci is an architect and adjunct professor at Polytechnic of Bari, Italy. She has a PhD in Architectural Representation and her approach of research is distinctive in its integration of multiple disciplines, including art history, architectural theory, and photography. She focuses on exploring aspects of visual perception and how these can be translated into images.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Sisci is exploring the feminine imaginary as it applies to architecture from ancient to contemporary structures. She will explore this important question by trying to identify the types of architectural spaces that in different ways are connected with the female gender. In the course of a 6-month itinerary she will visit sites in Sardinia, Malta and Gozo, Türkiye, Crete, UK and Ireland, Norway, Greenland, United States, and Mexico.

In the Southwest, the Spanish first arrived in 1540. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado reached the town of Zuni while searching for the legendary “Seven Cities of Gold.” From that moment on, the history of the Native peoples—those living partly along the tributaries of the Colorado River and, more densely, along the Rio Grande—changed forever.

It is precisely at this point in history that my own journey through the Southwest continues.

When European explorers set foot in what is now the American Southwest, the ancestral people who had once inhabited the Four Corners region—Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah—and who had built great urban, cultural, and trading centers like Chaco Canyon, had already moved on. Since around 1200 AD, for reasons still difficult to pin down, what we now call the Ancient Pueblo settlements had been abandoned.

But history is the weaving of change, transformation, and continuity. New villages rose far from the old ones, and as people moved, so did an entire culture—shaped and reshaped by time, integrating differences yet remaining unmistakably itself.

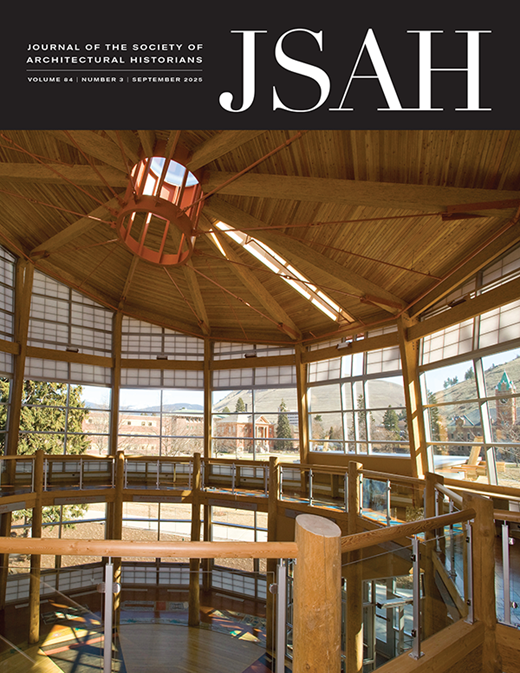

Fig.1 Map of the Pueblo Nation. Source: Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, Albuquerque

Today, the Pueblo Nations consist of twenty-one communities, each one with its own identity and dialect, grouped into four language families: Keresan, Tanoan, Zuni, and Uto-Aztecan. The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque is where these small city-nations converge, each bringing its unique voice and heritage to help build a shared, multifaceted narrative (fig. 1).

When I arrive, the first rooms hold a small exhibition dedicated to Pueblo architecture, from its origins to the present day. I’m surprised—yet it feels perfectly timed. Could I have hoped for more?

Panels approach the idea of architecture from different angles: the technical, with its tools; the cultural, as a form capable of embodying identity; and the symbolic, since for Native American cultures, architectural and urban space are far more than mere functional constructs.

I notice that the section devoted to symbolism takes up far more space than the one on technical aspects. It strikes me deeply, pulling me into reflection on my own reasons for loving architecture—on the rift between the inner motivations that drew me to become an architect and the kind of training I actually received. In Western architectural education today, symbolic thinking is virtually absent, or is substituted by technical ideologies.

The 21 Pueblo Nations are only a drop into a vast ocean of whole of humanity. Today more than ever, the architect seems compelled to respond to the needs of the masses rather than the singular, the exception. Perhaps this is why we have lost touch with the origins of architecture itself?

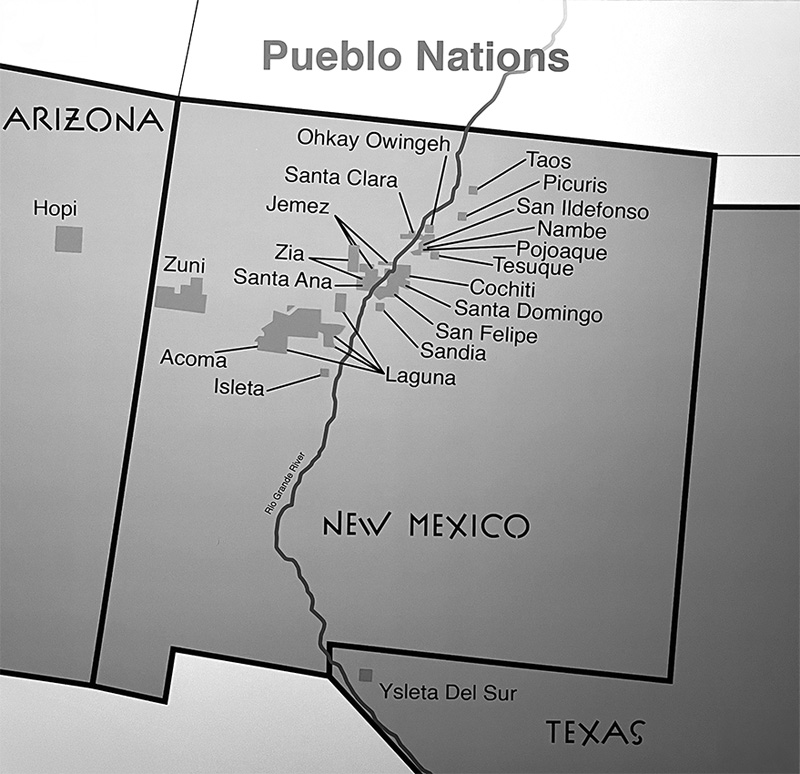

Fig.2 A Tewa Model of the earth. Sky-basket (top) and earth-bowl (bottom). (Drawing: Jeremiah Iowa. Source: Swentzell, 1990)

The Pueblo worldview is presented like this:

The Pueblo world, first of all, is an altogether hallowed place where the breath, or life energy flows through both the animate and inanimate realms in such a manner that even the house, kiva, and community forms breathe of that breath and are essentially alive.

The metaphysical assumptions underlying the Pueblo myths, stories, songs, and prayers define a cosmos that can be described as a contained spherical unit. The sky is referred to as a basket in a Tewa song. The references to the earth as a bowl are common and complete the other half of the world-sphere (fig. 2).

Opposites (sky and earth, light and heavy, male and female, warm and cold) are, then, also part of the contained spherical Pueblo world unit. The idea of the containment of opposites within the inclusive whole is in alignment with the universal Pueblo concept of simultaneity within which many levels of existence are recognized.

The Pueblo myths, stories, songs and prayers describe a world in which a house or structure is not an object—or a machine to live in —but is part of a cosmological worldview that recognizes multiplicity, simultaneity, inclusiveness, and interconnectedness. It is an ordered, but flowing, whole that reflects a cosmos strongly biased toward the gentle and inclusive qualities of the universe.

It is where cyclic rather than linear time is chosen; where movements are inward and spiral rather than outward and dispersed; where the ethereal and nonmaterial qualities of the cosmos are emphasized; where permanence of structure is not primary; where there is capacity to flow as well as sensuous concern with colors and shapes.

— Pueblo Space, Form, and Mythology, Rina Swentzill (Santa Clara), 1990

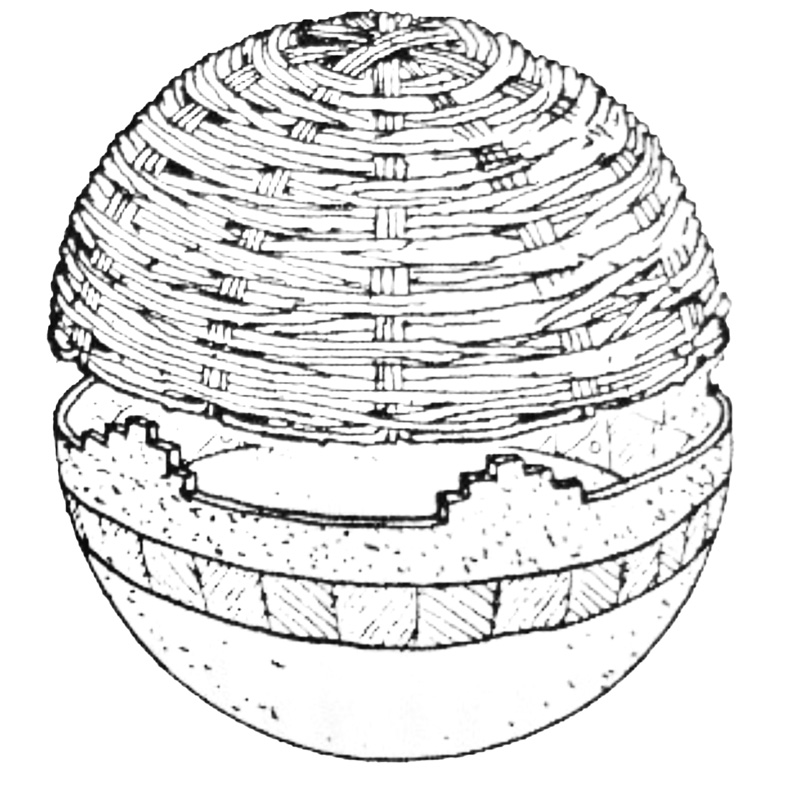

The names given by the Spanish—Pueblo, plaza, and kiva—are only modern descriptions. Despite many attempts to erase their culture, the native people continue to use their own Indigenous names for their villages: Heart Place, and Sacred Architecture (fig.3).

Fig. 3 Sacred configuration of Plaza- The town: houses, plaza and kiva. (Drawing: Jeremiah Iowa. Source: Swentzell, 1990).

The so-called Heart Place is the vital center—the spiritual and social nucleus—of Pueblo communities. It holds intangible value, yet it is also the organizing principle behind village architecture. It is a physical location, not necessarily geometric, but symbolic: a place of identity, memory, and ancestral connection. Its physical manifestations are the kiva and the plaza, representing the two sides of the Heart Place—the inner, underground realm, and the outer, public space—thus connecting opposite poles.

The kiva is the point of connection between the underworld and the world above: a “gateway” to the womb of Mother Earth. Sacred rites, conducted only by initiated members of religious societies, take place here. The plaza, by contrast, is the stage of public life—where dances and communal ceremonies reaffirm unity and belonging.

I think of the duality of this place-that-isn’t-a-place. The kiva, heavy with cosmic symbolism; the plaza, an empty expanse where architecture lives in the people themselves—where their presence transforms space into meaning. And I think of the absence of the concept of a periphery. The heart of the village is not simply a geometric center—erasing the very idea of “suburban” or “marginal.”

Five hundred years have passed since the course of things shifted, yet the echo of memory still lingers.

I set out to explore the still-inhabited Pueblos, fully aware of the limits set by their people. I will not cross them; for that reason, my words will sometimes have no corresponding image. Access to certain Pueblos is strictly controlled, sometimes requiring special permission. Even where entry is free, photography, audio or video recordings, and even sketching are almost always forbidden. The kiva and plaza remain entirely off-limits to outsiders.

The message behind these choices seems clear: a desire for peace, to avoid becoming a curiosity, and, above all, to finally be respected in their own will. And will—that is a key point of my journey. History has seen moments where the very right to will and self-determination was denied to entire peoples. The scar of that loss is visible everywhere—in every small Pueblo museum, where great emphasis is placed on the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, which restored tribal sovereignty, and the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, allowing tribes to run their own education and health programs.

Coexistence here is fragile, uneasy. The only way to resist erasure is to have roots that run deep—deep into the heart of the earth.

The first Pueblo I come across is Santo Domingo—not my original destination, but I’m so close that I decide to take a quick drive through. What I find is a simple, rural village of adobe homes clustered near the Rio Grande. The urban layout is regular and dense: long parallel blocks of houses facing each other, and in Santo Domingo Street, two kivas are built right into the fabric of the town. At the eastern entrance stands the large Spanish church, or mission. Easter has just passed, and almost every doorway is decorated for the occasion. My loop through the village ends at Brenda’s Hamburgers, where, for just a few dollars, I get the perfect American-Mexican burger.

Following the river upstream, I arrive at Taos Pueblo—a place where, in 1992, UNESCO decided that the village was so significant it should be a World Heritage Site (it had already been declared a National Historic Landmark in 1990). Access here is ticketed; no tribal chief decides who enters anymore.

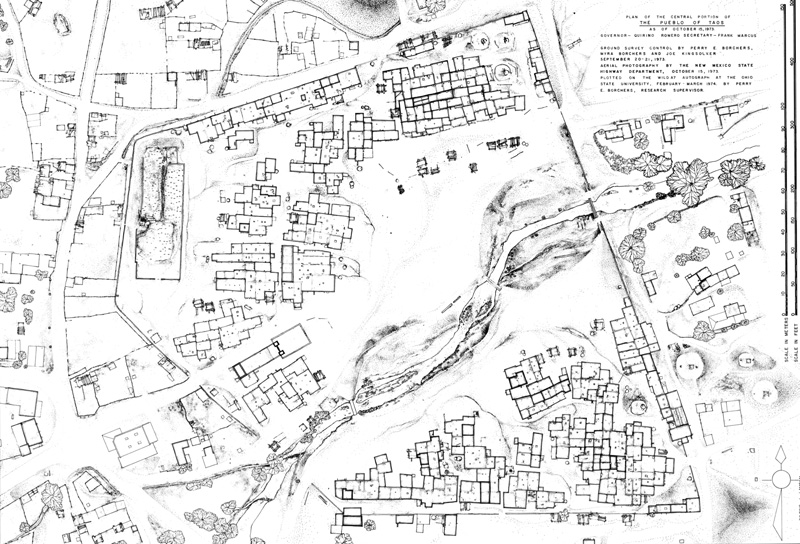

Fig. 4 Plan - Pueblo of Taos Central Portion, Taos Pueblo, Taos County, NM Drawings from Survey HABS NM-102 (Source: Library of Congress).

Fig. 5 View of the northern part of Taos, with the Rio Pueblo de Taos in the foreground.

The geography of the place is striking. The Rio Pueblo de Taos cuts through the settlement, dividing it into two halves. On either side, blocks of adobe dwellings face each other, oriented differently from one another, leaving an open space near the river (figs. 4, 5). The walls are adobe bricks coated with straw-and-mud plaster. Wooden beams support the roofs, and doors, windows, and ladders are also made of wood. Ladders connect floors from the outside; no building rises more than four stories, but since the height of each block varies independently, no single structure represents the whole (fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Taos Pueblo. View of the north block with pole platform in the foreground.

The kivas are set along the eastern edge of the settlement, still protected. The village no longer feels truly lived in—more like a tourist attraction now. Many residents have turned their homes into small craft shops. It’s not what it once was, but I don’t judge them; this is the mark of the contemporary world everywhere, and each time I see it, it feels bittersweet.

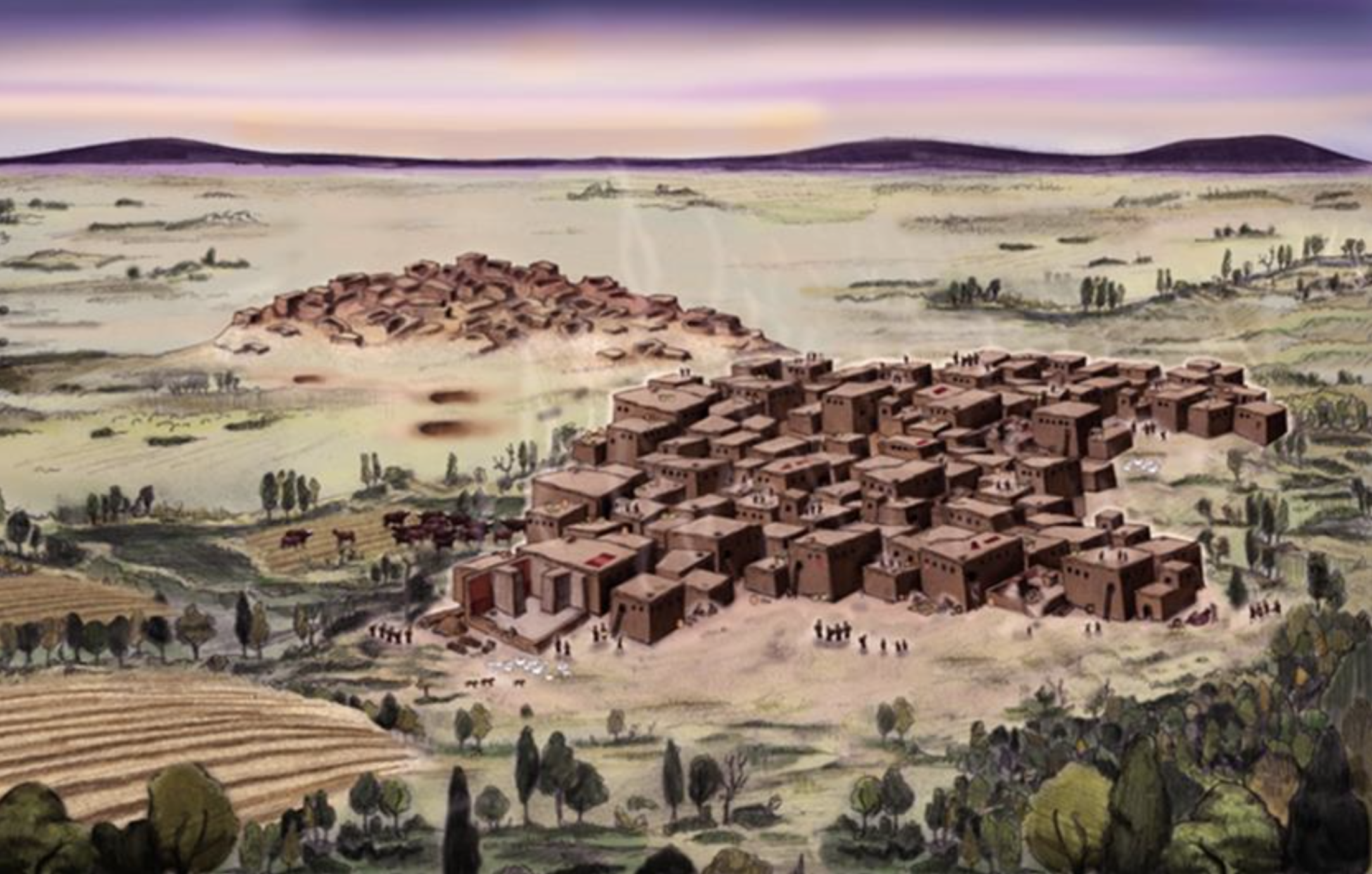

In its own way, the architecture of Taos Pueblo reminds me of Çatalhöyük (figs. 7, 8). Eight thousand years separate the ancient Anatolian settlement from Taos, and yet the resemblance is uncanny. Both are clusters of individual dwellings built side by side—here with shared walls, but originally without doors or windows, accessed only from the roof via ladders (figs. 9, 10). Perhaps it’s inevitable that starting from the same basic elements, humanity sometimes arrives at the same solutions. Still, I find myself wondering why, out of countless possibilities, these two distant peoples ended up creating such similar forms.

Maybe that’s part of why I wanted to come here—to this place remote in geography and time. Walking through Taos Pueblo allows me not just to imagine but to experience a reality long gone, one that has, in different moments, been part of many peoples’ histories. It’s a tangible reminder that there is no single History—only multiple histories, streams of time that converge and diverge endlessly, shaping many possible worlds.

Fig. 7 Çatalhöyük , East and West Mounds. Although this is only a reconstruction of what the village of Çatalhöyük might have looked like, when placed alongside images of Taos Pueblo it creates an intriguing visual short circuit, suggesting that the two villages could be contemporaneous and not too distant geographically.(Source: Çatalhöyük Research Project).

Fig. 8 Taos Pueblo. Construction detail clearly showing how the two housing units share a wall and its supporting beam.

Fig. 9 Detail of the adobe dwellings in Taos, where the arrangement of individual housing units with external wooden ladders is still visible.

Fig. 10 Elevation and Partial Plan of North Apartment - Pueblo of Taos Central Portion, Taos Pueblo, Taos County, NM Drawings from Survey HABS NM-102 (Source: Library of Congress).

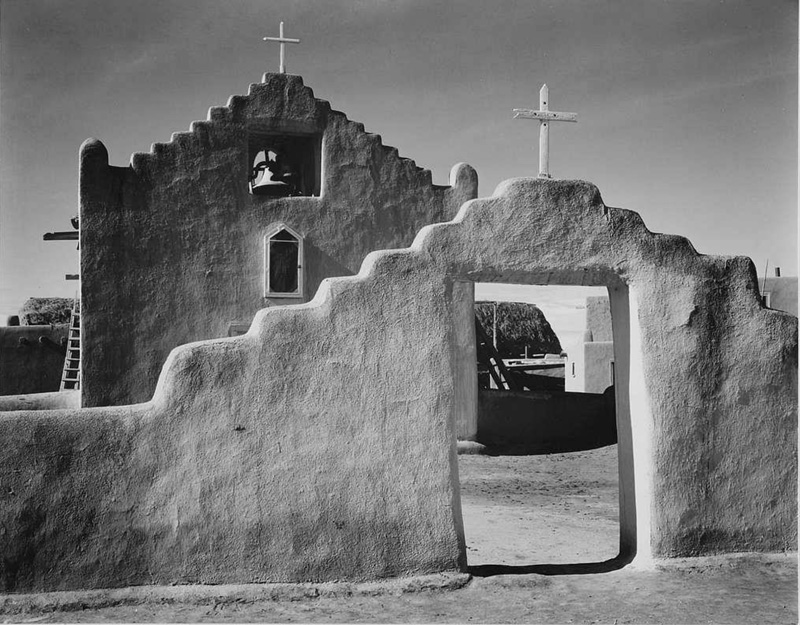

On the western side of the village stands the Mission of San Geronimo, built in the 17th century (fig. 11). It marks the starting point of the guided tour, which then moves on to the cemetery, also to the west. I find the same sequence at Acoma Pueblo. There, after being welcomed in a museum-like setting—entrance ticket in hand, bus ride up to the mesa—the visit begins with the Mission of San Esteban del Rey, also built in the 17th century.

Fig. 11 Mission of San Geronimo, Taos Pueblo. Ansel Adams 1941. (Source: National Archives)

This choice—beginning the story of a people with the story of a conquest—is something I see and yet don’t fully understand. On one hand, it makes sense: the arrival of the Spanish is both a traumatic wound and the moment this culture entered the current of Western history. On the other hand, I wonder why they don’t start the story with themselves at the center?

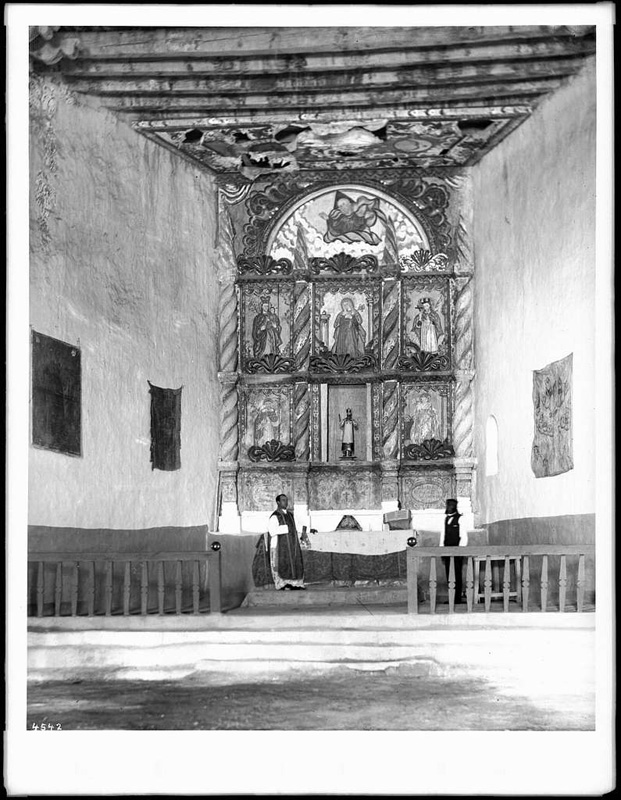

Slowly, I realize the answer is layered. In Acoma’s case, the church of San Esteban was built directly over their ancient kiva. The deepest conflict was waged on the terrain of religious—and therefore social—culture. The guide explains that their acceptance was never passive; it was an act of survival. The proof lies everywhere, even in the church architecture—like the twisted columns of the Baroque altar, where Acoma artisans carved naked men and women floating along the spirals (fig. 12). This was their way of resisting the Catholic—and Western—tendency to diminish women’s role. Among the Acoma, women are as vital as men, their social role central and enduring. Of all the possible differences to emphasize, it is this one they chose to preserve in stone.

Fig. 12 Priest at the altar in San Esteban church at the Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico. James George Wharton 1886. (Source: University of Southern California. Libraries)

Fig. 13 Stairway carved into the crevices of the rock of the mesa on which Acoma Pueblo stands.

Acoma—Sky City—sits in western New Mexico, not far from Gallup. Its position made it a kind of fortress, protected and isolated. Until recently, the only way to reach it was to climb a steep staircase carved into the mesa’s rock (fig. 13).

Even now, Acoma has no running water, no sewage system, no connection to the electrical grid—a fact that has contributed to its depopulation. The architecture resembles that of Taos, but without strict preservation laws, many houses have been restored, modified, or modernized alongside the traditional adobe structures with their removable wooden ladders (figs. 14 -19).

The first time I see Acoma from afar, it reminds me of small mountain villages in Italy. That mental leap erases the distance—geographical or cultural—between us. I recognize the strange instinct to build in places that seem hostile to life but are profoundly beautiful to live in (figs 20, 21).

Figs. 14-19 Alleys of Acoma Pueblo. The dwellings are generally built in adobe, but there are also houses made with roughly hewn stone blocks. Some houses have been perfectly restored in an effort to preserve their original appearance.

Fig. 20, 21 The boundaries of Acoma Pueblo coincide with the edges of the mesa. Reaching the rim and looking out from the village offers an extraordinary view of the canyon.

Reaching Acoma requires a long approach, each curve in the road making it appear first distant and compact, then suddenly close—and then vanishing again.

I decide to look deeper into why this community chose such a singular location. The answer surprises me, once again bringing me back to the symbolic depth at the heart of Pueblo architecture. In Acoma’s founding myth, the central figure is a woman called Tsichtinako—the Thinking Woman—a creative force whose tool is thought. She lives beneath the surface of the earth, from which all things emerge. From her come two other women, Iatiku and Nautsiti, who, once brought to the surface, are taught how to plant corn, build homes, and perform ceremonies. They are also given the task of founding Acoma—on that very mesa, which had always been waiting for its people. Even today, the Acoma honor Iatiku and Nautsiti as their ancestors, believing that mesa to be their destined place (Keresan name of Acoma is haaku meaning "a place prepared").

At this point in my journey, my wish to encounter what remains of the original Pueblo architectural vision is only partially fulfilled. Much of it, I realize, may be beyond my understanding simply because I belong to another culture. Yet despite that, I feel clearly that these vast expanses of desert, canyon, and mesa are full of stories and humanity. They are not empty, nor abandoned. They are lands bound by a deep alliance.

The final stop on my Southwest itinerary gives me the chance to understand, with both mind and heart, the true meaning of Heart Place.

At Zuni Pueblo, I enter without great expectations, perhaps worn out by my long days in the desert. As usual, my first stop is the Pueblo Cultural Center to gather information and ask my standard questions. This time, however, I receive an unexpected answer: at 4:00 p.m., in the Plaza, there will be a sacred dance—and I am welcome to watch, so long as I do not step into the Plaza, take photos, make recordings of any kind, and remain on the roof of the house they indicate (fig. 22). This is not a performance for tourists—it is for the people of the Pueblo.

Fig. 22 Zuni Pueblo. One of the many signs I encountered in the pueblos that explicitly prohibit taking photographs. This one in particular emphasizes the ban on photographing the community while they are performing their religious practices.

It feels like a gift—a reward for all the patience, wandering, and long days on empty roads; for the dozens of motels and breakfasts of tortillas and chile sauce. So I wait, sitting quietly in my car, until I hear music: singing, and the deep, steady beat of a drum. The empty streets begin to fill, everyone moving in the same direction toward that low, resonant rhythm.

I join the flow and climb to the spot they’ve shown me. On the rooftops surrounding the Plaza, hundreds of people gather for the ceremony (fig. 23).

The voices grow stronger, and at last, I see the Plaza below—filled with masked dancers moving in perfect unison. The masks hide their identities and the source of the singing, creating a powerful sense of abstraction. They wear traditional clothing, stunning turquoise necklaces, colorful feathers, and moccasins.

The ceremony unfolds with a precise rhythm—dancers, ceremonial leaders, and spectators who toss coins into the Plaza between dances. The women all sit in the Plaza, the elders in front, the younger ones behind. Their role is to distribute offerings. When the dance pauses, baskets of food and goods are brought to the center and handed out, starting with the eldest women.

Fig. 23 Kia’nakwe Gods Dancing in Plaza. Bureau of American Ethnology

It does not matter that the ceremonial leaders wear baseball jerseys and clay masks, that some of the dancers are overweight, or that the offerings include cans of cola, packaged snacks, and slices of pizza. None of this diminishes the integrity or the force with which something ancient still flows through these gestures—binding the people together after centuries. The past is not past as much as the future is present, past and future can wait now for a moment.

The Heart Place is the architecture of people.

Fig. 24 My hand next to one of the many petroglyphs at Petroglyph National Monument in Albuquerque.