-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Incomplete Remains: Interpreting Mining Company Towns in Chile

Sarah Rovang is the 2017 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

The original railroad that ran through the Atacama Desert, connecting the string of northern Chile’s historic nitrate mines to its port cities, today very nearly matches Route 5, the Panamerican Highway. Plunging through the heart of the Pampa, Route 5 is punctuated only by roadside memorials and signs marking the sites of the long-abandoned nitrate towns, called salitreras. Many of these are not only visible from the roadside, but can be reached via a bit of off-roading. On the drive from Antofagasta to Calama, we did exactly that, pulling the car off the highway and trekking a few hundred meters out into the desert. At this particular salitrera, whose name I never learned, the best preserved buildings were long rows of packed-earth worker housing. The roofs were absent, but the bleached and desiccated palm fronds blanketing the floor of a few houses were clearly fallen roofing material. Faded house numbers and the remnants of colorful interior paint were the only hints of individuality in the dwellings along this anonymous street. I climbed up to the roofline to get a better sense of the space. From this vantage point, I could almost make out the ruins of the next salitrera up the road.

This stretch of Route 5 is remarkable, but within the context of Chile’s history, it’s hardly exceptional. It’s hard to miss the impact of mining on Chile’s built environment. Dotted throughout this narrow country are countless historic and active mines—silver, copper, nitrate, coal, and lithium most prominently. Alongside the historic port architectures I discussed in my previous post, mining sites constitute another lynchpin in Chile’s growing heritage tourism sector. Of these sites, the company towns of Sewell (copper) and Humberstone (nitrate) are perhaps the best known. Both possess decidedly utopian intentions, are UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and have been extensively restored and redeveloped to support tourism. However, that’s where the similarities end.

Sewell

Sewell is perched high in the Andes, about three hours away from central Santiago, on an expansive parcel of land owned by CODELCO, the nationalized copper mining company of Chile. Visiting Sewell means booking a tour with an authorized guide, a long drive on a hulking tour bus, and passing through an official checkpoint to access CODELCO land. After the checkpoint, the last hour of the drive covers land so stripped bare it is simultaneously Martian and post-apocalyptic. As the road winds its way to Sewell, vistas open of decimated land stained green by oxidized copper remnants and current mining operations painted in phosphorescent hues; a postmodernist industrial distopia. The visitor’s first view of Sewell is the town’s old cemetery crumbling into the hillside over a parking lot filled with CODELCO buses. The second view is a dizzying composition of wood-frame buildings impossibly situated on a precipitous mountainside.

Sewell’s lifeblood and the source of its copper was El Teniente, an active mine that is today one of the world’s largest underground copper mines. Founded in 1905, Sewell was Chile’s first copper mine company town. The town was occupied until the 1970s, by which point CODELCO had decided that it was more economical for the miners and their families to live in Rancaqua, a town off company land more than an hour away. Preservation efforts to conserve the remaining buildings began in the 1990s, and in 2006 Sewell was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.1 Today, though miners drive behemoth modern rigs nearby, only tourists climb the grand escalera (or great staircase) that runs through urban Sewell’s core. Situated on a steep slant, Sewell’s designers devised wood-frame worker housing and service buildings and steel industrial structures uniquely suited to this hostile and topologically challenging environment. As at most other company towns, the majority of technological and structural innovation was applied to the industrial sector (the copper concentrator built in 1915 is still in use today).2 Yet, even with the requirements of building on a vertiginous Andean mountainside, the architects of Sewell adapted traditional timber-framing to a unique urban layout reflecting of the values of the company founders.3 Some buildings are stuccoed or plastered, but all are painted in brilliant hues, striking even amidst the low-slung clouds obscuring the mountainside.

The capital at Sewell, as at so many other Chilean copper and nitrate mines, came not from within the country, but from North American and Great Britain. Anglo-American financiers brought with them not only the technological savoir-faire to build mining operations but also cultural ideas about how a company should be run, and how those ideas should be expressed in architecture. The balloon-frame mansions that I described last month in downtown Iquique thus found their analogs in mining towns. The Norteamericanos who founded and ran Sewell only constituted 5% of the town’s population, but nevertheless made a dramatic impact on its culture and society. Workers at the mine were divided into A, B, and C roles. The Norteamericano minority held all of the A-role positions and lived in single-family dwellings segregated from the rest of the worker housing, further up the mountainside.4 Although all of the A-role housing was demolished before Sewell became a UNESCO site, the remaining structures give a vivid glimpse into its hierarchical society. A guided visit to Sewell begins in the Teniente Club, a building reserved for A-rolers and their guests, complete with a ballroom, dining rooms, and a heated swimming pool. For a moment, one can even enjoy the illusion of being in a turn-of-the-century club in New York or Chicago, until the views from the big bay windows spoil the effect.

A view from the second-floor ballroom at Sewell’s Teniente Club.

Teniente Club drawing room.

Swimming pool reserved for Norteamericanos in the basement of the Teniente Club.

Built as an urban agglomeration over several decades, the wooden buildings (and one-off concrete structure dating to 1958) reflect changing stylistic trends—the Teniente Club’s tall ceilings and crown molding are a stark contrast to the c.1930s/1940s mining school down the hill. Though the onsite signage goes to great lengths to emphasize the pragmatism and economy of the architecture (with “no place for unnecessary ornamentation”), the mining school nonetheless picks up the horizontal lines of International Style architecture and the sweeping curves of streamline moderne.5 This building hints to me that despite the town’s remote location, the administration remained plugged in to contemporary architectural trends, and that the desire to look as well as function like a modern mine town exerted some influence in the design decisions made for this building.

The single concrete structure in Sewell, constructed 1958. At that time, there was a plan to replace all of the older wooden buildings with concrete ones, but after trying it once here, that plan was abandoned.

The former mining school, which is today the mining museum. Beneath the plaster, this is purportedly still a wood frame building, but it’s hard to tell that from the outside.

The tour of Sewell begins at the top of the hill with the Teniente Club and winds its way down, through worker housing blocks for those on the B- and C-role, and the numerous recreational, religious, and educational facilities provided to give worker life structure and meaning outside of the copper mine. Outside of questions of style, the architecture of Sewell invariably reflects the beliefs and mores of its founders, including social mobility, freedom of religion, temperance, and the right to education. Numerous services and amenities were designed to serve the town’s robust administrative middle class, and the church’s Catholic iconography is notably restrained in order to keep the space interdenominational.

Though I’d booked a tour in English, it turned out that our guide spoke only Spanish. As a result, I spent much of the visit watching the other people on our tour, considering their reactions and wondering why they had left a lovely summer Saturday in Santiago to trek around in 40 F temperatures at Sewell. What did the experience of this place mean to them? I was seeing a company town with utopian aspirations, but what were they seeing? Of the thirty or so people on our tour, there were only two other Norteamericanos (also academics). The rest, judging by a glance I got at the tour roster, were Chileans. That ratio seemed about the same for the rest of the other tour groups visiting on the same day. The lack of English language reviews of Sewell online led me to (wrongly) believe that this was not a terribly popular attraction. But on the day we visited, there were at least 5 or 6 other tour groups of similar size running simultaneously. Adding to the crowd were those there to see a youth exposition of traditional Chilean dance taking place on the town’s central plaza. It quickly became clear that despite its remote location, Sewell is a site of living memory for many Chileans. After posting some photos of my visit to Instagram, the Chilean mother of a friend messaged me to say how meaningful the images were, as her great-grandfather had mined at Sewell.

The working class culture around mining is a pervasive aspect of Chilean nationhood. Unlike in South Africa, where mine owners intentionally used language barriers and ethnicity to discourage the formation of trans-cultural African worker movements, and where white unions often worked to the detriment of their black counterparts, Chile possesses a largely solidified working class culture. The narrative of the Chilean worker as a national “type” dates back to Nicolas Palacio’s polemical (and deeply problematic) 1904 book La Raza Chilena (The Chilean Race). In this work, Palacio valorizes the much-maligned Chilean worker, dubbed the Roto (or “broken”) Chileno. In reclaiming this term, Palacio denies any significant Latin contribution to the Roto Chileno’s character, instead attributing the unique culture and features of the Chilean worker to the miscegenation of Teutonic people and the indigenous Mapuche. This work, which fueled both early worker movements and anti-immigration campaigns, was similar to other contemporary works in that it argued that the Chilean character was based in mestizaje, or racial and cultural hybridity.6 But Palacio’s work is emblematic of a broader shift in Chilean culture towards recognizing and celebrating workers, and particularly miners, alongside heroes of the Independence and the War of the Pacific.7 Not coincidentally, this transformation paralleled the rise of worker movements and increasing class consciousness.

Mining is today still a mainstay of the Chilean economy, copper mining alone accounting for 50% of its exports, and the miner retains a vaunted places within the national imaginary.8 Remember the 33 Chilean miners who were trapped underground for 69 days back in 2010? Though the rest of the world was equally rapt by that story of survival and endurance, the way Chileans understood that event was undoubtedly shaded by the country’s longer narrative about miners and mining. I wonder then, if Sewell, located close to Santiago, and with a significant portion of its original architecture intact, might be considered the Chilean equivalent to Colonial Williamsburg, a metonymic place that conveys broader and more persistent narratives of national identity. Indeed, the presence of active mining within sight of the historic company town makes it easy to perceive an unbroken linkage to the past. The interpretive choices at Sewell strengthen than connection, by placing focus on the restored spaces where working- and middle-class Sewellians lived, worshipped, saw movies, and went bowling. Most visitors, I suspect, don’t make the trip for the formal qualities of Sewell’s architecture, but rather for the human stories contained within its walls.

Humberstone

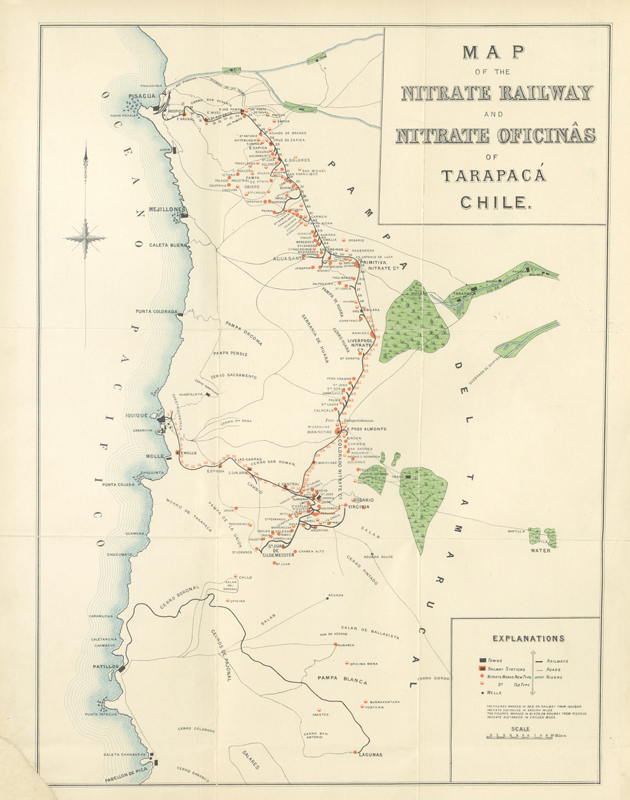

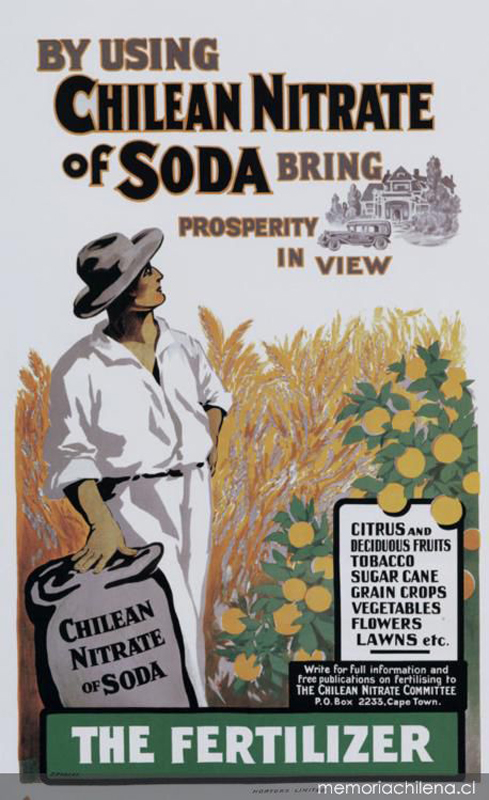

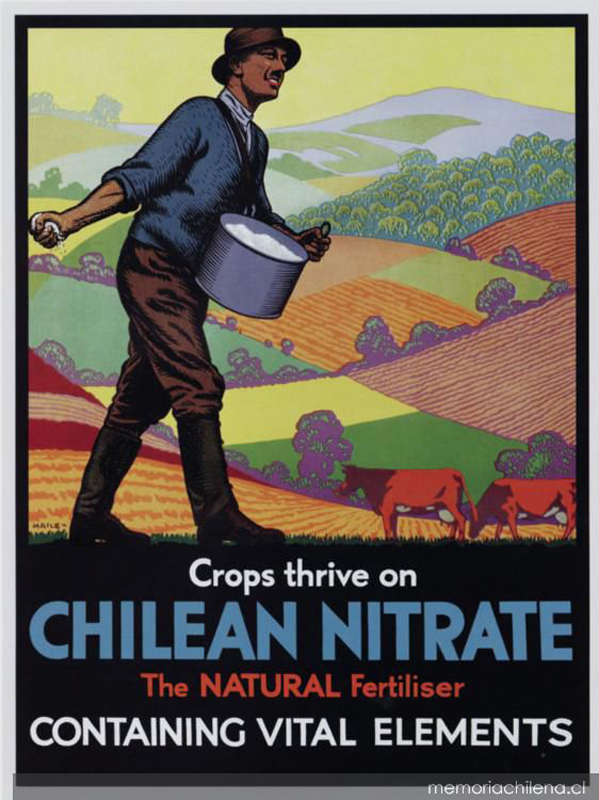

More than one thousand miles north of Sewell is the nitrate mine and company town of Humberstone. Located 45 minutes east of Iquique, the drive to Humberstone loops up the coastal range and onto the Pampa, the elevated plain of the Atacama Desert. Today astrobiologists study the Atacama to learn about how life might survive on Mars—only the hardiest of microorganisms can eke out an existence on the Pampa, where the last rain may have come decades if not centuries ago.9 It is also here that the world’s largest mineralogical deposit of nitrates (also known as saltpeter) was discovered in the 1820s. When runoff from the Andes seeped up through the flat plain of the mineral-rich Pampa, long, stratified bands of different mineral contents were distributed through the process of evaporation. The fact that all of Chile’s former nitrate mines follow a straight path parallel to the coast is not for economic reasons, as I had assumed, but in fact geological ones. From the 1880s until the early 1930s, somewhere around two hundred salitreras were established along this strip of nitrate-rich earth stretching north along the Pampa from Antofagasta to Pisaqua. Each of these salitreras was connected to nearby port towns via a railway, allowing the so-called “white gold” to reach the rest of the world. The nitrate boom coincided with—and also precipitated—the rise of industrialized agriculture across the globe, yielding a fertilizer capable of restoring depleted fields to fecundity.

Map of Nitrate mine distribution in 1890 from Iquique to Pisagua, image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

A South African poster advertising Chilean Nitrates, courtesy of “Afiches Epoca del Salitre,” Mineria y Cultura, accessed January 30, 2019, http://www.mineriaycultura.iimch.cl/afiche_salitre.html.

A poster advertising Chilean Nitrates to Britain and Ireland, courtesy of “Afiches Epoca del Salitre,” Mineria y Cultura, accessed January 30, 2019, http://www.mineriaycultura.iimch.cl/afiche_salitre.html.

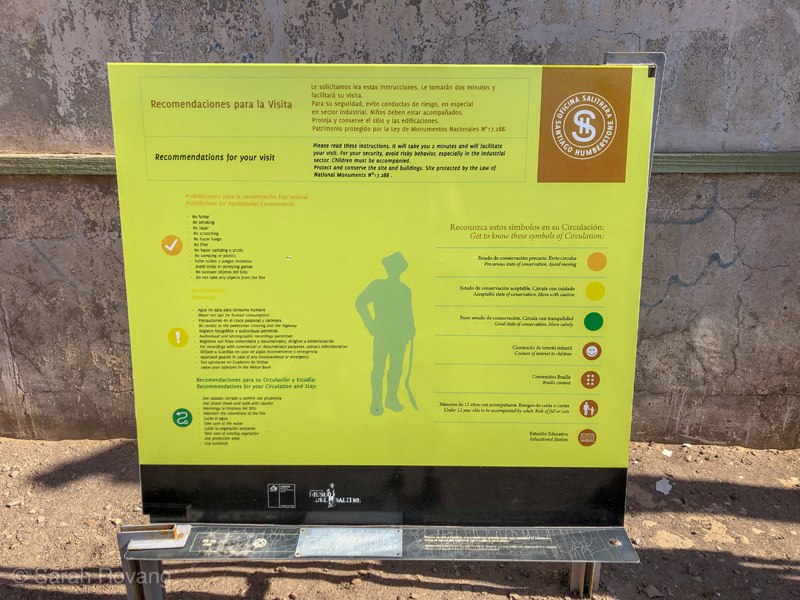

Despite the lack of ground moisture, Atacama mornings are often characterized by an impenetrable fog. Once that fog burns off though, there’s just barren land, blue sky, and fierce sun. We arrived wearing jackets and by noon were down to our shirt sleeves, and on our third application of sunscreen. The visitor experience at Humberstone is decidedly more self-directed than that at Sewell: rent a car, roll up, buy several large bottles of water, and hope your tetanus booster is up to date. Near the site’s entrance, there is a sign introducing the color-coding system by which buildings are marked as being in good, fair, and dangerous condition.

It is not immediately clear how massive the site is (for the record, it’s 573.48 hectares, or 1417 acres).10 The row of medium-size houses for middle-managers and engineers that flanks the entrance initially blocks everything behind it: a fully-fledged company town complete with dozens of intact buildings, and the ruins of the industrial mining and processing plant. While I spent much of my time at Sewell people-watching, Humberstone is so extensive that it was hard to find any other people to watch, though quite a few other visitors arrived by bus and car over the course of the day. A five minute drive down the road from Humberstone, the smaller and less visited salitrera of Santa Laura offers a complementary heritage experience: here, the industrial portion of the plant has been well preserved, while the housing has been completely destroyed, leaving only foundations.

A view overlooking the housing section and central plaza of Humberstone.

The intact industrial core of Santa Laura, which retains enough structural integrity to demonstrate the process through which nitrate-bearing ore is refined and turned into consumer-grade saltpeter for export. Gravity was used extensively during this process, which is why many of the industrial structures are quite tall.

Humberstone is notable not only for the sheer amount of worker housing preserved, but the massive plaza at its core, which, like Sewell, articulates a particular vision of worker life. There’s a theater, a hotel, a general store, a public fountain, and an outdoor bandshell. Nearby are a swimming pool and a school. Having seen some truly bleak and desperate worker environments during my fellowship explorations so far, I was not expecting to find a resplendent Pueblo Deco theater in the middle of the Atacama Desert.

Humberstone’s theater; a uniquely Atacama Desert variation on the Pueblo Deco style popular in the North American Southwest.

Humberstone’s theater; a uniquely Atacama Desert variation on the Pueblo Deco style popular in the North American Southwest.

The Art Deco facade of the hotel, which also contained entertaining spaces for visitors and guests.

The pulperia, or general store.

A sculptural, Art Deco inspired public fountain at the center of a courtyard reminiscent of that of a hacienda.

The back of the bandshell in the central plaza, looking out onto the stage.

A swimming pool with bleachers directly adjacent to the central plaza.

An Art Deco-inflected school with almost a dozen classrooms.

The same railways that transported processed nitrate to nearby ports also were responsible for bringing in building materials in. Rather than turning to the construction strategies traditionally employed on the Pampa, which include both an adobe-like earth-block building method and a wattle-and-daub tradition using bamboo grown in oasis towns like Pica, the Anglo-American managers at Humberstone (and many other Atacama salitreras) opted to import methods they were familiar with—at the start, mostly timber framing. Humberstone, which was active from 1872 to approximately 1960, encompasses a range of styles and architectural approaches to the extreme aridity of the Pampa. In the middle of the Atacama, direct sunlight feels scorching, but full shade verges on chilly. As a result, creating shelter is largely a matter of moderating sunshine, as in the hotel’s ballroom and bar, where light filters gently through a ceiling made of bamboo draped over wooden crossbeams. Arcades and shaded porches are frequent features throughout the site. The architects of Humberstone drew from a pan-American and pan-historical vocabulary of forms, picking up a hacienda courtyard here, an Art Deco flourish there. Though the first sequence of buildings was made out of wood, frequently roofed with corrugated tin, later additions increasingly employed concrete, particularly in public buildings. Many of the most prominent public structures are products of the 1930s, during which time a program of reform sought to bring new services and amenities to the workers and families.

Without the fear of rain, roofing only needs to provide protection from the sun, as in the hotel ballroom with its bamboo roof.

Porches and shade structures are also common in Humberstone’s worker housing.

The interior of a working housing block, showing the combination of wood framing and adobe fill held in by wire.

The heart of Humberstone’s urban plan is not its church or its theater, but the pulperia, or general store. The infrastructure to provide for all of the alimentary and material needs of the town’s workers was extensive, including cold storage areas for meat and produce, and industrial-sized ovens for baking bread. With the sprawling intricacy of a Roman bath, the pulperia now functions as Humberstone’s engaging interpretive center. The interpretive signage here and across the site effectively points out the ways in which Humberstone, like Sewell, followed a rigidly hierarchical model, given architectural form in housing type and site arrangement. The director’s vaguely Arts & Crafts bungalow might have been that of an upper-middle class family in the American Midwest, but the bulk of workers, particularly those who were without families, shared rooms in what were little more than barracks. And at Humberstone, as at many salitreras, payment was often given in the form of tokens, which could only be spent at the general store. Contemporary observers of the nitrate trade speculated that mine owners might have sometimes made more from their general stores than they did from the nitrate industry, a suggestion that intimates a kind of economic slavery endemic in the whole salitrera system 11. That the general store was the sturdiest and most complex building on the site was surely no mistake; directly inside the pulperia’s main entrance sits Humberstone’s de facto bank counter, from which paychecks or tokens would be distributed.

The dry goods counter at the pulperia, which has been restored to appear as it might have in the mid-twentieth century.

The pulperia also sold other material goods that miner families would have needed in Humberstone, such as fabric for making clothes.

Immediately within the entrance was the counter from which worker paychecks (either in tokens or cash) would have been distributed.

Incomplete Remains

Since it was built over a number of years, Humberstone’s plan doesn’t have the same legible, symmetric geometry of other utopian company towns. However, just a few hours south is Maria Elena, the last of the original salitreras still occupied, and a compelling example of utopian town planning. Focused on a square park, the central plaza is surrounded by most of the town’s main public buildings—the church, the theater, the general store (now a market), the bank, and a long civic building that was recently converted into a municipal museum. From the square central plaza, the town radiates out as a series of concentric octagons. The outer rings are mostly occupied by housing— long, one-story structures wrapped by shaded porches. Time and continuous occupation have transformed them from standardized worker housing into individualized dwellings, painted in diverse shades. Just east of town are the remains of the former nitrate processing plant. The town still relies on nitrate mining and processing, but this happens in a newer, modern facility a few miles from the town.

Satellite image of Maria Elena and the historic nitrate processing plant, courtesy of GoogleEarth.

The church at Maria Elena.

The famous Art Deco theater of Maria Elena.

Maria Elena’s new museum, the Museo del Salitre, is housed here.

By this point in my fellowship year, I’ve visited many de-industrializing cities, bled dry of their economic lifeblood and without a younger generation to support the aging population that remains. That’s what I expected to find at Maria Elena, but with mining activity still providing jobs for the residents, there was none of that sense of desperation. If not excessively prosperous, there was a sense of activity and purpose. The market bustled, there was a line at the bank, and we were far from the only people eating lunch in the park. The town was in the full Christmas spirit, with decorations in the park and a nativity scene set up next to the bank. There was even a star hung from the old processing plant.

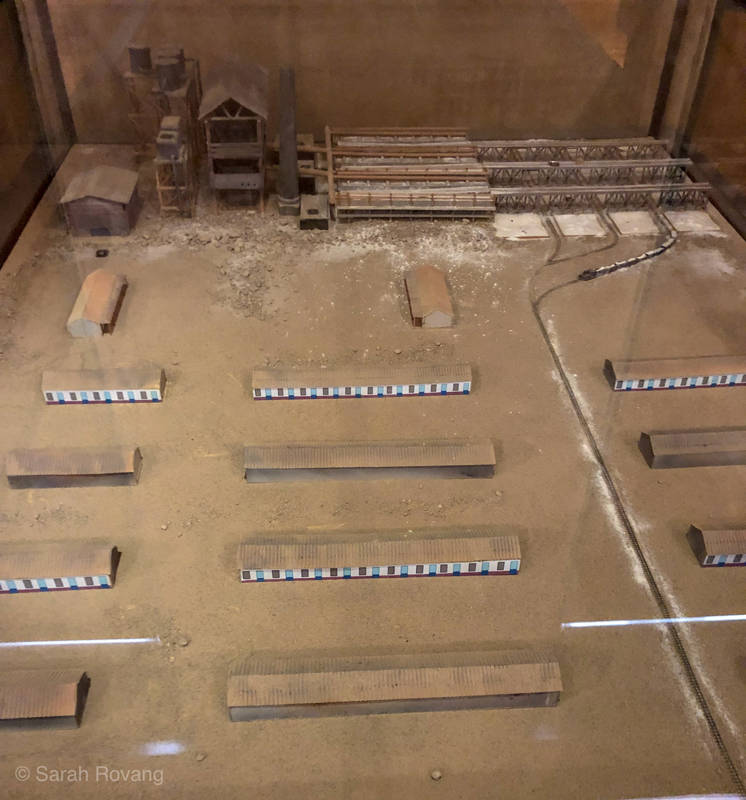

We wandered over to the museum, only to learn (following the logic of so many small town museum hours) that it was closed, but would reopen at 4 pm. John trotted out his high school Spanish and haltingly explained our reason for being there, and the kind docent on duty relented and gave us a tour. I’ve now seen a lot of museums about Chilean mining, ranging from rather dated regional museums to the slick, modern Museum of the Atacama Desert. But the museum in Maria Elena was the first and only interpretation to really dig into the spatial dynamics and architecture of nitrate mining. A series of dioramas showed the development of salitrera layout in three stages—the preindustrial, the early industrial, and the present-day. It was the middle diorama that looked the most familiar—a planned company town directly adjacent to the nitrate fields and the processing plant. But it was also missing so many of the urban features I’d become familiar with. The diorama showed only the processing facility and a few bleak rows of barracks-style worker housing. Where was the school, the theater, the expansive pulperia? In each of the preserved mine town examples I’d seen so far, there had been an implicit or explicit dedication to labor condition reform and worker development, made clear by the inclusion of certain building typologies and their privileged placement within the town. Perhaps these museum-ified company towns were not the whole story of what early industrial mining life was really like in Chile.

A diorama at the Museo del Salitre in Maria Elena showing the middle stage of salitrera development: rows of worker housing adjacent to the processing plant.

At our final stop in Northern Chile, an ecolodge near the oasis town of Pica, I asked our host Marco, a Peruvian geologist, about what we’d seen, describing the disparity between the preserved and interpreted salitreras and the version we had seen in the diorama at the Maria Elena museum. Marco explained that Humberstone and Maria Elena are not the “real” salitreras of the early twentieth century—instead, these are relics from a later period in which the government partially took over the Chilean nitrate trade. In 1929, the nitrate market had collapsed after German chemists invented an artificial process for synthesizing the compound. At that point, most of the salitreras in Chile shut down and those that remained were put under partial government control. Humberstone, Maria Elena, and the few other salitreras that continued production into the 1930s and later were significantly altered, often with the intent of improving working conditions. Looking at both the style and typologies of the Humberstone structures dating to this post-1929 period, it is impossible to avoid being reminded of contemporaneous New Deal architecture in the United States. I even wonder whether the architects of the reformed vision for Humberstone were directly inspired by their Norteamericano counterparts in the PWA. Was the construction of that glorious Pueblo Deco theater perhaps also a public works project, a make-work construction job to help out the ailing nitrate industry?

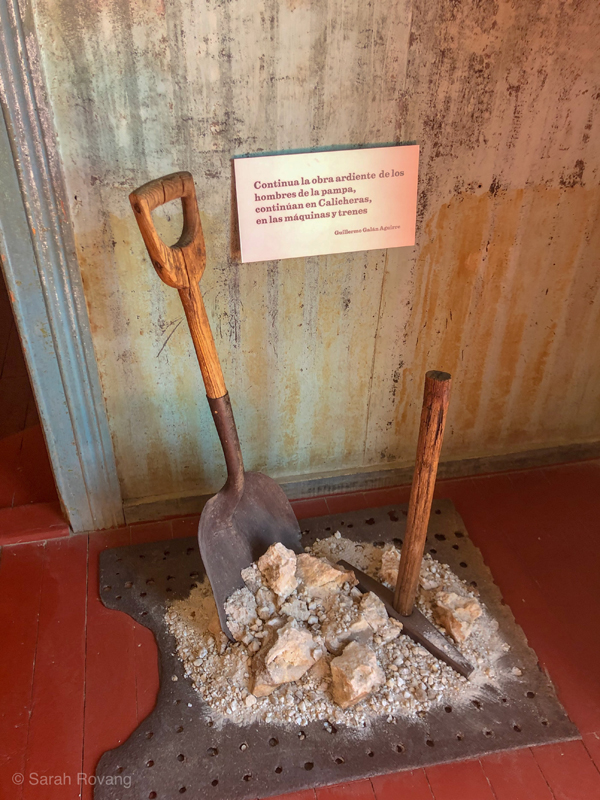

I told Marco about our escapade off Route 5—the ruins with the packed-earth worker housing. There, the industrial structures seemed to have vanished entirely, or were perhaps so distant that we never found them. There were no signs of the amenities preserved at Humberstone—the school, the theater, the hotel. The whole idea of public space, so critical to the other salitreras we’d visited, was missing. Before that period of reforms in the 1930s, Marco told us, nitrate mining had been an unequivocally “nasty business.” Surviving documentary evidence from that earlier era of mining backs him up on this. Worker accounts, such as that of Elías Lafertte, describe a peripatetic lifestyle on the Pampa, frequently searching for new opportunities, enduring toxic, dangerous work, and never quite able to get ahead due to the exploitative “token system” of payment. Lafertte also witnessed the 1907 Iquique Massacre in which the army killed some two thousand striking workers and family members. This event is a reminder that the Chilean government, which would later tout its worker reforms, long abetted the exploitation of those same workers in service of enriching the national coffers.12

Because the built remains of this earlier period of mining have either been lost, lack interpretation, or are not easily accessible, how can these places be made real to the public? How do we avoid losing these stories or forgetting that exceptional examples like Humberstone and Maria Elena tell an incomplete story? In some sense, it’s the same challenge to that architectural historians face working with plantation houses in the United States. Those plantation houses that have survived, particularly those that have been preserved and opened to the public, are often exceptional in the quality of their architecture and/or in the kinds of historical narratives they tell. The extraordinary nature of the architecture can belie or obscure the fact that these “beautiful houses” were supported by the institution of slavery. Likewise, it’s easy to look at Sewell or Humberstone and think that being a miner in 1920s was probably not so bad, even if we know that isn’t the whole story. The spaces at both of these sites that intentionally remind us that this isn’t the whole story are also the most powerful: at Sewell, a room containing a mural showing an infamous 1945 mine disaster that killed 355 people, and at Humberstone, a memorial and museum dedicated to the 1907 Iquique Massacre. These homages to human events remind us that historical sites aren’t just snapshots of a synchronic moment, but rather diachronic spaces that inscribe a multitude of lived experiences. With that in mind, public historians can begin to peel back the utopian, reformist layers—Sewell was at its start a collection of simple covachas, or wooden shacks, and early Humberstone likely looked very much like the simple packed-earth salitrera we found off Route 5.

The Sewell tour includes a stop at a mural responding to the deadliest mine disaster in Chilean history, a 1945 incident where many workers due to smoke inhalation.

Humberstone houses a moving and effective memorial museum dedicated to the 1907 Iquique Massacre. The interpretation provides necessary context, describing the economic conditions that had prompted the strike, and the army’s fateful decision to respond with force.

A worker memorial at Humberstone’s Iquique Massacre Museum.

The day we visited Maria Elena, we also drove 20 km south to the salitrera of Pedro de Valdivia. Abandoned as recently as the 1990s, Pedro de Valdivia has been declared a national monument but lacks any official interpretation other than a plaque at its front gate. Throughout the town, families have marked their names in spray paint, commemorating who lived where and in what room. Someone—maybe former residents, maybe their children, living today in Maria Elena—still maintains the landscaping on the town’s main street, which is kept alive by a rudimentary drip irrigation system. A makeshift memorial at the town’s center pays homage to former residents, its spray-painted epitaph reading, “Para que nadie pierda la memoria porque soy parte de esta historia // y en medio de esta tierra mi voz geguira viviendo,” roughly: “So that nobody loses the memory, because I am part of this story // and in the middle of this earth my voice will live.”

I thought back to the nameless salitrera, which had no names inscribed, no written record on site to memorialize who lived there and when. What will happen to places like Pedro de Valdivia, which are so remote from Chile’s tourism hotspots? The sad, pragmatic truth of industrial heritage is that not everything can be saved, nor is curation and interpretation financially feasible at every site. Mass-produced sites, designed with the premise that both architecture and worker’s lives were fundamentally disposable, lose out to the reformed counter-examples, the utopian one-offs. But that grates against a basic and instinctual human desire to not be forgotten, and to mark our landscapes so that we will be remembered. As one resident of Pedro de Valdivia wrote, “Yo no estoy muerto, lo estare cuando no me recuerde” — “I'm not dead, I'll be dead when you do not remember me.”

- “Sewell Mining Town,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, accessed January 20, 2019, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1214. ↩︎

- “The Sewell Concentrator and its Astonishing Longeivity,” Sewell interpretive sign, photographed November 17, 2018. ↩︎

- “Functional Architecture for an Unusual Mountain Location,” Sewell interpretive sign, photographed November 17, 2018. ↩︎

- “The Sewell Elite: The North Americans,” Sewell interpretive sign, photographed November 17, 2018. ↩︎

- “Functional Architecture for an Unusual Mountain Location,” Sewell interpretive sign, photographed November 17, 2018. ↩︎

- Nicolás Palacios, “Race, Nation, and the ‘Roto Chileno’”, translated by Enrique Gauguin, in The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015): 213-216. ↩︎

- Ibid., 199. ↩︎

- For an effective visual explanation of Chile’s copper economy see Jeff Desjardins, “How Copper Riches Helped Shape Chile’s Economic Story,” Visual Capitalist, June 21, 2017, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/copper-shape-chile-economic-story/. ↩︎

- Rebecca Boyle, “The Search for Alien Life Begins in the Earth’s Oldest Desert,” The Atlantic, November 28, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/11/searching-life-martian-landscape/576628/. ↩︎

- “Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, accessed January 30, 2019, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1178. ↩︎

- Elías Lafertte, “Nitrate Workers and State Violence: The Massacre at Escuela Santa María de Iquique’”, translated by John White, in The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015): 240. ↩︎

- Ibid., 238-244. ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top