-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Malta: The Mother Island

May 3, 2025

by

Francesca Sisci, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Francesca Sisci is an architect and adjunct professor at Polytechnic of Bari, Italy. She has a PhD in Architectural Representation and her approach of research is distinctive in its integration of multiple disciplines, including art history, architectural theory, and photography. She focuses on exploring aspects of visual perception and how these can be translated into images.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Sisci is exploring the feminine imaginary as it applies to architecture from ancient to contemporary structures. She will explore this important question by trying to identify the types of architectural spaces that in different ways are connected with the female gender. In the course of a 6-month itinerary she will visit sites in Sardinia, Malta and Gozo, Türkiye, Crete, UK and Ireland, Norway, Greenland, the northeastern United States, and Mexico. All photographs are by the author.

_______________________________________________

Fig. 1. Cliff on the western side of the island of Malta.

In the heart of the Mediterranean Sea, 52 miles off the southern coast of Sicily, lies the archipelago of Malta. A small cluster of islands, where my journey in search of the original meaning of the word architecture continues.

The Maltese archipelago is made up of four main islands—Malta, Gozo, Comino, and Cominotto—and two small rocks, St. Paul’s and Filfla. These islands have a long and fascinating history, shaped by many different cultures. Over the centuries, they were home to the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, and Byzantines. Later, they were ruled by the Arabs and then by the Kingdom of Sicily, until 1530, when they were given to the Order of Saint John.

The Knights of Malta are probably the most famous part of the island’s history. They defended Malta from the Ottoman invasion in 1565, and during their 250 years of rule, they built the strong military architecture that still defines the capital city, Valletta.

But Malta’s story didn’t stop there. In 1798, the French took control of the islands, and in 1800 the British arrived. Malta remained under British rule as a protectorate until 1964, when it finally became an independent country.

Such a complex history is clearly reflected in the appearance of Malta’s main cities. In fact, expecting to arrive and find a typical Mediterranean island—small, filled with traditional buildings, and mostly inhabited by locals—would be a big mistake. Alongside a striking mix of architectural styles that blend both Northern and Southern European influences, you’ll also find large, modern neighborhoods with skyscrapers and trendy spots, often filled with people from all over the world. The population is incredibly diverse, and the island today feels more like an international hub than a remote Mediterranean outpost.

But Malta’s history goes back even further—and in many ways, it is truly one of a kind. The most recent study published in Nature dates the first human presence on the island to around 9,000 years ago (Scerri & Vella, 2025). It appears that some of the last groups of hunter-gatherers who survived the interglacial period settled here. So, the idea that Malta is a good place to spend the winter seems to be an ancient truth—one that quite literally goes back to the dawn of time.

Jokes aside, this discovery builds on research that began between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when archaeologists first started seriously exploring Malta’s prehistoric past. Over time, this work has led to the recognition of seven megalithic temples as UNESCO World Heritage Sites between 1980 and 1992: Ħaġar Qim, Mnajdra, Tarxien, Ta’ Ħaġrat, and Skorba on the island of Malta, and the twin temples of Ġgantija on the island of Gozo.

All of these were built between the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE, and they stand as evidence of a thriving civilization that lived on the archipelago during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods. Their advanced construction techniques and the widely accepted theory that many more temples once existed make this prehistoric complex unique in the world—both in scale and in architectural sophistication. Just to put things in perspective: the megalithic structures at Stonehenge were built about 1,400 years later.

Given the small size of the island (24 km long and 14.5 km wide), I decided to stay on the move for this trip—without setting a fixed itinerary, letting the spirit of discovery guide me. After spending some time in Valletta and getting a sense of its complexity and beauty, I headed toward the first archaeological site that felt right to visit: the temples of Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra. To get there, I crossed the island from the eastern coast to the western one. The short distance gave me the chance to explore the island’s inland landscape—gentle, quiet, and filled with typical Mediterranean vegetation.

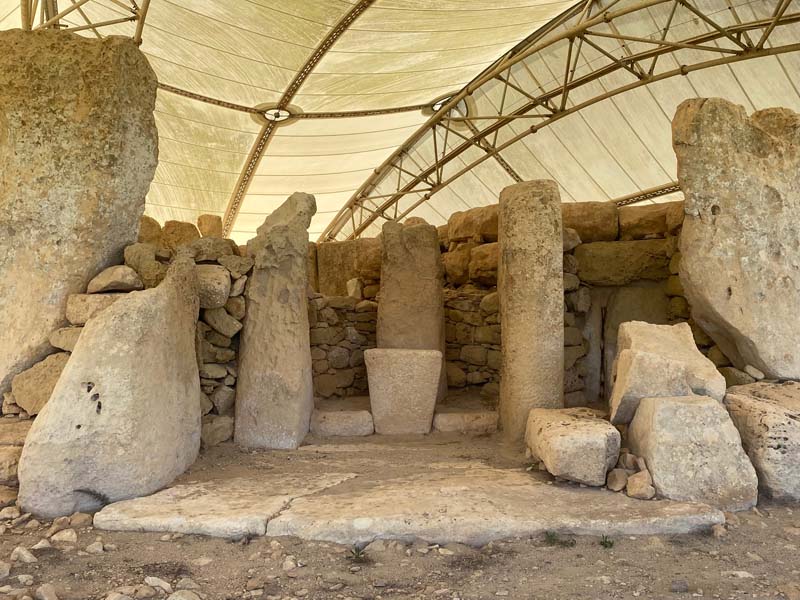

Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra stand just 500 meters apart from one another, perched on a rocky stretch of coastline about 200 meters above sea level. From there, you can see the islet of Filfla in the distance (fig. 1, 2, 3).

Fig. 2. View of the Mnajdra Temple with its protective shell. The temple stands just a few steps from the sea, facing the islet of Filfla.

Fig. 3. View of the Filfla islet from the stretch of coastline where the temples of Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra are located.

They are dated to a period between 5600 and 4500 B.P., and both were built using a local yellowish limestone that gives them their distinctive appearance.

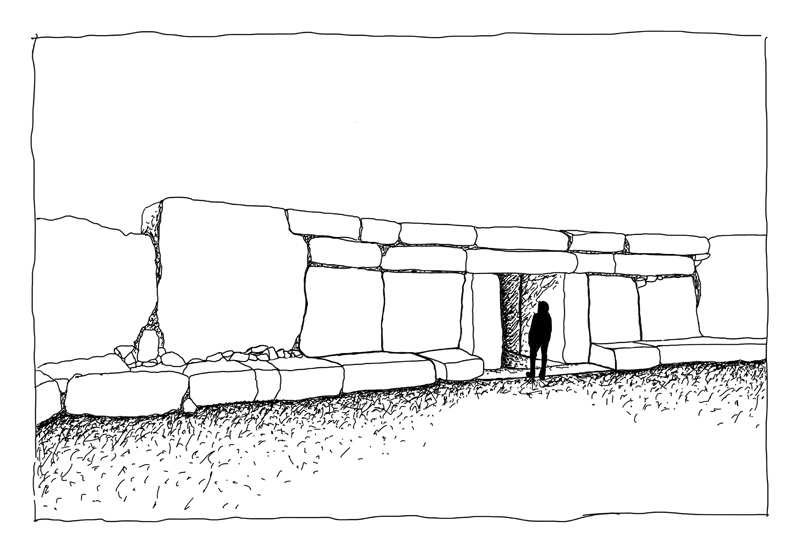

One feature shared by all the megalithic temples of Malta is the use of large, squared stone blocks, known as orthostats, placed above a raised platform (figs. 4, 5). The resulting sense of monumentality creates an experience that is deeply powerful—not just on an emotional level, but intellectually as well. This impression becomes even stronger when we consider that, at the time these temples were built, metal tools had not yet reached the archipelago, nor had the wheel been introduced.

Fig. 4. Entrance to the Ħaġar Qim Temple. Drawing by the author.

Fig. 4. Entrance to the Ħaġar Qim Temple. Drawing by the author.

Fig. 5. Rear view of the Ggantija Temples, Gozo.

And yet, the civilization that inhabited Malta for centuries left behind clear signs of remarkable technical skill. In his book Malta: Origins of Mediterranean Civilization, the Italian archaeologist Luigi M. Ugolini explores this idea in depth. He goes so far as to say that the temples—and prehistoric Maltese craftsmanship in general—should be considered a “classic.” The maturity Ugolini refers to is something that can be felt even beyond scholarly analysis. Unlike what one sees, for example, at Çatalhöyük, here there is no doubt that the builders of these temples possessed a strong ability to plan, design, and represent their ideas in more than one form.

A surprising prehistoric model, now housed in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta, perfectly complements an engraving carved into one of the large stone walls at the Mnajdra temple (figs. 6, 7).

Fig. 6. Engraved drawing depicting the entrance to a temple. Mnajdra Temple.

Fig. 7. Model of a single-cell temple. National Museum of Archaeology, Valletta.

What fascinates me most about these discoveries is how clearly they reveal the ancient bond between imagination and representation—how this connection has guided human beings since the very beginning. Imagination came before technique, not the other way around.

I can’t help but think that if that tiny model weren’t behind glass in a museum, labeled with a note reminding us of the thousands of years that separate us from its maker, we might easily mistake it for something made yesterday—or even imagine it as a vision of tomorrow.

It’s so small that I could hold it in the palm of my hand, like an amulet. And in that moment, by simply feeling it against my skin, I might grasp a meaning deeper than thought—a meaning passed from the hands that shaped it directly to mine, silently and powerfully.

All the Maltese temples appear today mostly as ruins, and none of them has preserved a roof—not even partially. Yet, both the carved drawing and the small model suggest that some form of roofing once existed, even though the floor plans of the various temples are far more complex than that of a simple single-chamber structure.

Several hypotheses have been put forward regarding the construction technique used, but one of the most widely accepted remains the idea that the roofs were built using a corbelled system. This technique involves gradually projecting stone blocks inward until the space is closed at the top, creating a sort of false vault.

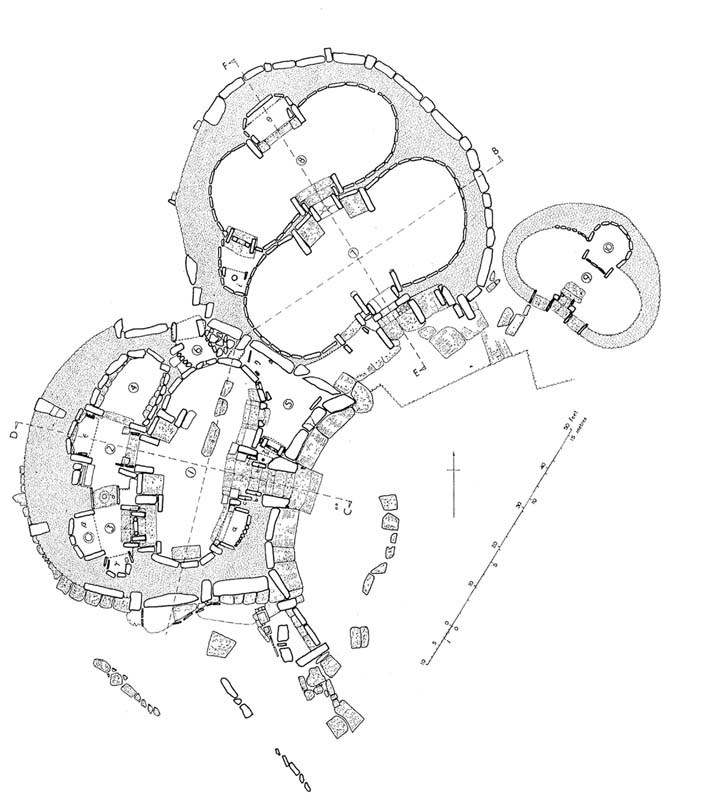

Another feature that makes these temples truly unique within the prehistoric landscape is their extraordinary architectural form. What we see today is the result of a long process, composed of multiple phases, which is why many sites include more than one temple built side by side.

For example, the shape of the entire complex at Ħaġar Qim, as it appears to us now, is the outcome of five centuries of continuous modification, additions, and redesigns that followed the construction of its four distinct temples—built between 5600 and 4500 B.P.—and enclosed within a single outer wall.

Fig. 8. Plan of the Mnajdra temple complex, with the small trefoil temple on the right, the north temple at the top, and the south temple at the bottom left. Evans, 1971.

Fig. 9. One of the many stone statues found in the Maltese temples, all based on the same stylistic scheme. Ugolini, 1934.

When looking at the floor plans of the Mnajdra temples (figs. 8, 9) and Ġgantija, a particular spatial pattern emerges: each is composed of a series of apses arranged symmetrically along a central axis. These apses gradually narrow as one progresses deeper into the temple. This organic layout has led scholars to believe that the structures served a specific and deliberate purpose—an idea reinforced by the absence of domestic objects or everyday tools within the temples.

This highly elaborate spatial configuration appears unrelated to practical or technical needs and instead seems to respond to symbolic or ritual functions. For this reason, the word “temples” is used to describe them in its broadest, most inclusive sense.

Alongside the various architectural and archaeological theories, some researchers—most notably Marija Gimbutas in her book The Language of the Goddess—have pointed out a curious resemblance between the shape of the temples and that of certain figurines found inside them. What is commonly referred to as the “Venus of Malta” actually describes a type of statuette frequently uncovered in these sacred sites.

These figurines are remarkable not only for their number and size but also for their consistent design: a corpulent figure, seated with legs crossed or folded to one side, hands resting either on the knees or over the belly. This is a highly stylized representation, and it further suggests the level of cultural sophistication reached by this Neolithic society.

The gender of these figures is not clearly defined, but due to their abundance, it’s often assumed they symbolized fertility and prosperity. This theory is supported by archaeological findings—at Tarxien, for example, some of these statues were discovered placed inside apses, directly in front of low altars likely used for votive offerings (figs. 12, 13). In certain cases, the figurines appear as a pair: two identical figures side by side, echoing the layout of two anthropomorphic temples placed next to each other (figs. 8, 10).

Fig. 10. Twin Statues. Xagħra Stone Circle, Gozo.

Fig. 11. One of the apses of the Mnajdra temple, Malta.

Fig. 12. Apse with altar. Hagar Qim temple, Malta.

Fig. 13. Apse with altar. Ggantija temple, Gozo.

Now, although the gender of these figurines is not explicitly defined, the themes of abundance and fertility are traditionally associated with the feminine realm in archaic cultures.

Yet, the very absence of clear gender markers is particularly intriguing. Perhaps it suggests a deity that does not belong to any one gender, but rather encompasses them all—a divine figure that transcends binary distinctions, embracing a more universal, all-encompassing form of existence.

More than anything else, these temples embody an immense collective effort, carried out over centuries by an entire civilization. Maybe that’s why walking through them today still feels like such a powerful experience.

Their scale is unusual—completely out of proportion with the surrounding landscape. This lack of alignment with the context doesn’t feel accidental; rather, it seems like a deliberate attempt to engage in a dialogue with something invisible, something other. The apses, though made from massive stone blocks, somehow feel soft and welcoming. They seem to respond to movement—opening up and narrowing down, gently guiding the body through space (figs. 8, 11).

Dozens of temples like these, which likely once dotted the island in such a distant time, suggest that this small patch of land was a crucial place—an outpost and stronghold at the heart of the Mediterranean. A place that, for centuries, has seen a constant flow of people coming and going, welcomed again and again: a Mother-Island where temples stand as Body-Architecture.

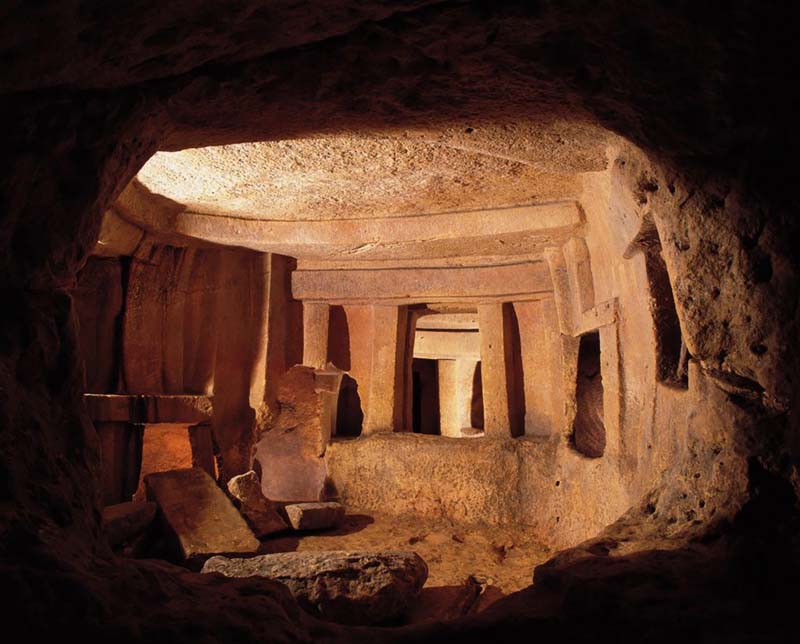

The last archaeological site I chose to visit was the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum, an extraordinary underground architectural work used for burial rituals, carved between 6100 and 4500 B.C. and spread across three distinct levels with about fifty chambers. Entering it feels like stepping into the belly of the island—like going below deck on an enormous ship that has sailed through time, guarding the secrets of its countless crews deep within.

Photography is not allowed inside, mostly for technical reasons—but even if it were, the place has such a suspended aura that you’d hesitate anyway. The Hypogeum’s main chamber is its most iconic feature; it looks almost like the carved-in-rock counterpart of the above-ground temple façades (fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Main chamber of the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum. © viewingmalta.com

Among the many votive figurines found in the burial pits, one stands out as one of the most striking in the global archaeological record: The Sleeping Lady (fig. 15). Her name comes from her pose—a small, full-bodied woman lying curled up on a mat in what appears to be eternal rest.

That image—her stillness, her form—stayed with me. She herself seems like an island, a body to land upon and finally rest.

Fig. 15. The Sleeping Lady. Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum.