-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Tales between Genova, Turin, Tianjin, and ‘Invisible Cities’

Jun 9, 2025

by

Amalie Elfallah, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Amalie Elfallah is an architectural-urban designer from the Maryland–Washington D.C. area, which she acknowledges as the ancestral and unceded lands of the Piscataway-Conoy peoples. As an independent scholar, her research examines the socio-spatial imaginaries, constructions, and realities of Italian colonial Libya (1911–1943). She explores how narratives of contemporary [post]colonial Italy and Libya are concealed/embodied, forgotten/remembered, and erased/concretized.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Amalie plans to travel along the eastern coast of the United States before departing for Italy, China, Albania, Libya, and the Dodecanese Islands in Greece. Her itinerary focuses on tracing the built environment—buildings, monuments, public spaces, and street names—linked to a selection of Italy’s former colonies, protectorates, and concessions from the early 20th century. All photographs are by the author, except where noted.

_____________________________________________________

Turin, Italy [Torino, Italia]

Empirical imagination endures not only in monuments and architecture but even in the fabric of metro maps and street signage. After my transit from Milan to Turin, I was surprised to discover a metro line to Bengasi at Stazione Porta Nuova. The sign caught my eye as the glass envelope around me disappeared while descending down the escalator to the metro platform. Stazione Bengasi was named after the main city in eastern Libya—what some may refer to as the Cyrenaican port of Benghazi. It opened four years ago, in April 2021, although I must have missed it during my first visit that same year as a student. Italy’s existential connection to Libya is subtly inscribed as in many other cities and towns which superficially mark its former colonial possessions. Today, many of these spaces serve as significant nodes—prominent points of transit. Although tracing streets and names might seem irrelevant to observing the built environment, I hoped that visiting these places and the transformations they underwent would foster ideas and further points of departure for this fellowship.

On the platform at the Benghazi Station, I found two particular buildings featured on a wall decal, suggesting their historical significance: one being the Scuola Elementare Re Umberto I, inaugurated in 1931, and the customs outpost built in 1912 (Fig. 1). Walking up to the street level from the underground, the former outpost emerged as a prominent form dividing the sea of cars from the metro entrance. There was no particular monumental detail or aesthetic value to the building, except its clean symmetry from a purely utilitarian plan (Fig. 2). Pizzeria Marhaba and Café Bengasi were visible from the landmark, along with the normal patterns of pedestrian traffic. "Piazza Bengasi" was chiseled in stone, demarcating the public space (Fig. 3). The area, inhabited by a diverse community, felt very similar to what I saw around Piazza Derna (Fig. 4), another public space named after another Libyan port city, located north and opposite the city center. The ongoing development of Piazza Bengasi was evident, as a prominent façade facing the square displayed a poster on the scaffolding that read “Piazza Bengasi / Guarda al futuro,” meaning “Bengasi Plaza / Look to the future” (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1 – Wall decal in Bengasi Metro Station, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 2 – Former Outpost building outside Piazza Bengasi Metro Station, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 3 – Piazza Bengasi street sign (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 4 – Transit platform next to ENI Gas Station, Piazza Derna, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 5 – Advertisement seen at Piazza Bengasi, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

As I continued walking around the city, it became clear that various public squares and street names had been inaugurated or later renamed to honor newly occupied territories in the early twentieth century—such was the case with Via Eritrea (Fig. 6), Piazza Massaua (Massawa), and its corresponding metro station (Fig. 7). I remembered walking through a cluster of streets named after Italy’s former occupied territories in the southwest side of Turin—what might be considered the periphery. After a fair amount of walking along a towering concrete wall labeled “military zone,” I began wondering whether the area I was heading to had become a model neighborhood or a place meant to house people with some “connection” to the territories inscribed in the streets. Via Somalia (Fig. 8) was the midrib to its branching streets: Via Rodi, Via Bengasi, and Via Tripoli. Another Via Rodi is located in Turin’s city center which I saw within 1928 tourist guide, thanks to the generous hospitality of the Historic Archive of the City of Turin (Archivio Storico, Città di Torino). Rodi—a reference to Rhodes, one of the Dodecanese Islands occupied by Italy in 1912 and held until the German occupation in 1943—remains inscribed downtown (Fig. 9).

Fig. 6 – Via Eritrea, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 7 – Massaua Cityplex Cinema in Piazza Massaua, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 8 – Street signage of Via Somalia at the boundary of a military compound (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 9– Via Rodi, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

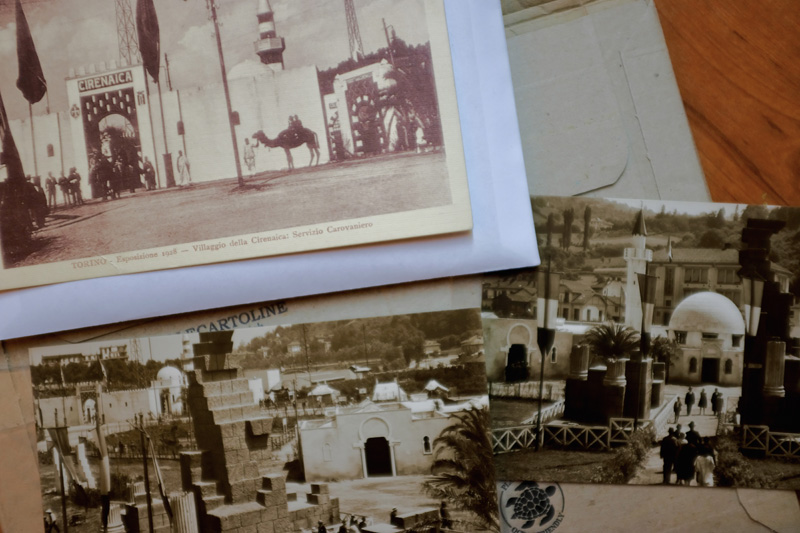

While certain streets still bore the marks of colonial presence, other traces had quietly faded—including the memory of the 1928 Exposition of Turin (Esposizione di Torino). This event, once grand in its imperial staging, now lingered only in fragments. I remembered missing my bus stop and accidentally crossing the bridge over the Po River from the city center a day earlier than planned, arriving at the former grounds of the “colonial villages.” Though I had hoped to share the maps and images I encountered in the Historic Archive of the City of Turin, doing so would have required formal permission and with that, the cost of time. “Model” villages of various occupied territories, including the Somalian Village, Tripolitanian Village (Western Libya), Cyrenaican Village (Eastern Libya), Eritrean Village, and ruins of Rhodes were built on those grounds in an area referred to as Mostra Colonie or Mercato Colonie. While I found only general views in the city archive—along with a few close-up images in my second-hand collection (Fig. 10)—I wondered who had been brought to populate these displays. Who was exported to be staged, observed, perhaps even subjugated, for the sake of spectacle? Who built the mock-up mosques, houses, and markets in these “villages?” And the walls of those “ruins?” In finding the most appropriate and ethical way to share these places, I found myself once again returning to the ethics of research despite the necessary incisions that reveal the presence of materials often hidden, uncomfortable, or altogether dismissed. The archive, after all, was not simply a record of empire; it was also a site of erasure, omission, and selective memory, what some may refer to as “the hidden case of barbarism.”

Fig. 10 – Postcards depicting the “Cyrenaican Village” area during the 1928 Turin Exposition (Source: personal archive of Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 11 – Via Dogali remaining from the infrastructural traces of the Colonial Exhibition from the 1928 Turin Exposition, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 12 – Walking around the leisure program partially on the former grounds of the Colonial Exhibition from the 1928 Turin Exposition, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Though temporary, these constructed spaces left a partial imprint. Today, Via Dogali (Fig. 11)—named after a battle near Massawa in what is now Eritrea—traces the edges of the former colonial exhibition area. It was perplexing to consider that the name of a battle with apparent anti-colonial resistance would be memorialized in Turin on the very grounds that commodified and staged colonized cultures for public consumption. And yet, this was just one of many such contradictions worth questioning when walking past spaces now repurposed for leisure layered over histories like the 1928 Turin Exposition (Fig. 12).

This layering of history resurfaced again at another site on my itinerary built in 1933: the Monumento al Carabiniere (Fig. 13). Years ago, I first heard about the monument in the work of artist-based researcher Alessandra Ferrini. In her film Sight Unseen (2019), Ferrini used the monument as a node through which to question the “unseen” narratives of Italy’s colonial past in Libya. The film has since materialized in her recently published monograph, Like Swarming Maggots: Confronting the Archive of Coloniality (2024). She speaks with Italian historian Alessandro Volterra, and discusses a series of photographs documenting the capture and execution of Omar al-Mukhtar, the anti-colonial resistance leader in eastern Libya. Volterra, along with Maurizio Zinni, later published that research in Il leone, il giudice e il capestro: Storia e immagini della repressione italiana in Cirenaica, 1928–1932 (2021). To leaf through that book—containing, for the first time, the “legally” released images of al-Mukhtar’s capture and execution in the concentration camp of Soluch in 1931—makes it incredibly difficult to revisit monuments like the Monumento al Carabiniere. Ferrini describes the “status” of the monument as a “memorial [that] celebrates the ‘heroic gestures’ of the Carabinieri armed forces between the 1860s and 1930s. It features the only effigy alluding to al-Mukhtar's capture on display on Italian soil, according to Dr. Volterra. Since Carabinieri were not responsible for his capture, as suggested therein, the monument can be considered a historical fabrication.” In many ways, these images—so deeply tied to an era of suppressed trauma for Libyans—endure in Italian public memory, often met with a blind eye. Just as bronze oxidizes with time, so too do the narratives cast into the monument’s form.

I finally saw the monument in person as my previous knowledge remained from primary materials and my second-hand archived collection (Fig. 14). As described in a contribution to ‘The Funambulist 54: Colonial Continuums’ (2024) which briefly mentioned the monument, the “section of the northwestern plinth portrays Italian soldiers and Ascari among a mysterious figure in a traditional Libyan jard (also known as holi)—a cloth iconographically associated with the resistance leader.” Standing before it, though, the scale of the sculpted figures—the Ascari, military officials, and anonymous Libyans—conveyed a presence far more imposing than expected (Fig. 15). Nearly 1:1 in size, they felt eerily lifelike, especially when people basked in the grass of the park just meters away from the monument.

Fig. 13 – Monumento al Carabiniere (c. 1933) as seen today in the Royal Gardens, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 14 – Postcard of the Monumento al Carabiniere , Giardini Reali di Torino, Turin, Italy (Source: personal archive of Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 15– Northwestern plinth of Monumento al Carabiniere leaves the era that celebrated Italy’s occupation of Libya, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 16 – Details of a Libyan woman in a farrashiya at the Monumento al Carabiniere (c. 1933) as seen today in the Royal Gardens, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Stepping back from the monument, I noticed how the elderly figure cloaked in a jard seemed to compete in the hierarchy of the scene—rendering the celebration of the “carabinieri” as something spectral. What captured my attention, though, was a nearly hidden detail: the partial face of a Libyan woman sculpted behind the military figure who dominates the composition. The woman, though, is largely obscured from street view. One eye—just visible behind what appears to be a farrashiya (الفراشية), the traditional cloth that was often worn outside the home in Libya—emerges from behind the military official’s hat (Fig. 16). Though nearly hidden, this subtle inclusion raised questions about the sculptor’s intentions, the nature of the commission, and how such commemorative works can serve to mask or obscure certain narratives. Could this sculpted scene really be interpreting one of those photographs of Carabinieri posing with the Libyan resistance leader in the days before his public execution? Why, of all colonized geographies, is Libya the only commissioned scene on this monument? Like the name of public squares and the monuments that honor those who serve, the built is always cast with intention.

As I moved away from the monument toward the city center, the questions the monument stirred continued to follow me. Just minutes later, walking through the underpass to Palazzo Reale, I saw the words “Free Gaza” graffitied on a column—something I had seen countless times across the city (Fig. 17). This time, however, the message echoed with renewed and immediate resonance. What happened in Cyrenaica—the forced displacement and mechanization of concentration camps from 1928 to 1934—felt as veiled and concealed as the violence we witness today against the people confined in the Gaza Strip. When one considers brutal repression enforced by Italy’s fascist regime within the concentration camps across Cyrenaica of the 1920s and 1930s, followed by the anti-Semitic racial laws and internment camps later imposed on Arab, Italian, and other practicing Jewish communities living in 1940s Tripolitania (western Libya), it becomes clear that these mechanisms of immobilization were not isolated incidents. Rather, the camps were utilized as a broader, systemic ideology of racialized violence—a continuum etched into monuments, archives, and urban landscapes far beyond Europe.

And thinking back to the monument, just a few steps away, I wondered: how could these figures stand, sculpted in a public space, without the slightest acknowledgment of the narrative it was extracted from?

Fig. 17 – “Free Gaza” is written on a column at the underpass between Palazzo Reali and Monumento Al Carabiniere, Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 18 – One of many instances where ‘fasci’ — the fascist symbol depicting a body of reeds and an axe — remain materialized across Turin, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 19 – “Resistenza” displayed in front of an encampment at Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

If racial violence was once encoded in the language of Italy’s impero moderno, it also persists in the built environment—quietly embedded in bronze, buildings, and silence. Supposedly, the fasces on the Monumento al Carabiniere had been removed. While many symbols have been stripped from public view, other symbols endure with time. On my way to the city’s historical archive, I unexpectedly noticed the silhouette of fasces and swords—barely visible from the street—near the Società Reale Mutua di Assicurazioni (Fig. 18). This happened just after I passed the Museo Diffuso della Resistenza (Diffused Museum of Resistance). Beneath the museum’s title, a slogan promised to “diffuse” the meaning of “Resistance / Deportation / War / Rights / Freedom” from the era of Fascism-Nazism. I had hoped to find within its accounts examples of anti-fascist resistance in the colonies, especially alongside its permanent exhibition Turin 1938–1948: From Racial Laws to the Constitution. I could not help but think how powerful the mission of the museum, along with the history of the ‘partigiani,’ might be if it expanded its local inventory to Italy’s colonial past—its geographies of racialization, subjugation, and resistance to its former overseas territories.

As I tour and travel, I continue to look for that museum or exhibition in Italy that properly contextualizes the early twentieth century. What kind of building might hold or honor those histories? If such a museum or curriculum did exist, I imagine that the idea of Resistenza—as invoked in the anti-fascist anthem Bella Ciao—might resonate beyond Italy, extending unequivocally to other geographies outside the “global north.”

In the meantime, though in the temporal, resistance has been adopted on university campuses. In front of Piazza Leonardo at Politecnico di Milano, student encampments remain present throughout the school year and were seen in the month of April. Resistenza could be seen hanging on the fences that gated a cluster of tents on campus (Fig. 19). Another cluster of tents hung signage “against the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestine.” In this moment, the past and present converged, not only in language but in student declaration by refusing to forget what was and what is, even if their histories have not been met side by side.

Tianjin, China [天津 , 中国]

Italy’s imperial presence lingers not just across the Mediterranean, overseas, but past the Silk Road. In Tianjin, known in Italian as Tientsin, traces of Italian architecture, military installations, and commemorative monuments remain. Now branded as the “Italian Style Area” (天津意大利风情区), Italy’s former concession lies in Tianjin’s Binhai district. Signage with a “brief introduction of the Italian Style Area,” said the concession lasted from 1901-1946. Tianjin was carved by several foreign powers—including Japan, Russia, Austria-Hungary, France, and Belgium—after the Qing Dynasty ceded land following the Boxer Rebellion. These were no temporary outposts. The concessions were built into the city’s very fabric along the Haihe river. In a 1935 archival film produced by Istituto Luce, viewers are greeted with the words: “Welcome to Tientsin, the Italian corner of China—where our fellow countryman have built a model town." The once-celebrated “model town” is now a commodified cultural zone, immediately recognizable upon entering the bustling Dante Square (但丁广场), where “East meets West.”

Fig. 20 – Dante Square, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 21 – Tianjin’s concession map featured in the Memory Exhibition, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 22 – Popular spot known for the elderly whom have been spectacularized for diving into the Haihe river, bridge and riverwalk leading into Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

The only plaza in this district that allows the passage of vehicles is built around a statue of the Italian writer and philosopher, Dante Alighieri. The hustle-and-bustle of this roundabout makes it, itself, a tourist attraction. Mainly three-wheeled rickshaws (三轮车) with red canvas tasseled roofs, some decorated with flowers others with lanterns, ambulate around Dante along with people dressed as monkeys and clowns (Fig. 20). The monkey, in fact, represents Sun Wukong (孫悟空), the Monkey King—a well-known figure from the 16th century classic Chinese novel, Journey to the West. The Monkey King is a prevalent figure appearing across the country, I found the vast amount of monkey costumes around a prominent figure of the west with deep irony. I wonder if this urban condition manifested itself naturally…

Incredibly different from the standard yet ornate villas, on the corner of this plaza is a noteworthy building which hosted a public and free permanent Memory Exhibition (天津记忆百年天津工业展览馆). At the beginning of the tour, there is a map of the concession and how it was divided between its foreign dignitaries (Fig. 21). Surprisingly, the exhibition focused on the types of industries and famous individuals that lived in the area followed by an overview of Tianjin’s traditional crafts and delicacies. The experience of the exhibition culminated with a lengthy gift shop that formed a one-direction egress, twisting and turning through the former Italian era building in a way that made it feel entirely encased with program.

The experience through the Italian Style Area was vastly different from the activities that happened across and even on the river. Tianjin is famed on Chinese social media for hosting the “diving grandpas.” On the weekends especially, the bridge on the western corner of the Italian Style Area becomes a place of spectacle. Tourists and residents line the bridge and river walk to witness the elderly practice their mundane pastime of jumping into the river with an audience. Elderly gather, riverside, playing cards, exercising, and mingling with each other as onlookers pass by the stage (Fig. 22) just at the outskirts of the Italian Style Area.

Fig. 23 – Wayfinding map in Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 24 – “Quartiere ItalianO” awning in Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 25 – Typical street with commercial program fronting “Italian Style” buildings, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 26

While the riverbank buzzes with spontaneous energy, stepping into the Italian Style Area reveals a contrasting atmosphere—one that feels curated, stylized, and carefully branded. To navigate the former Italian concession, one might come across the ornate wrought-iron signposts that evoke a Florentine revival framing the cartoon-like maps of the Italian Style Area (Fig. 23). Is this place an amusement park? The area is branded as a “century Italian style fashion and commercial community / A New Way of Life.” And indeed, it is, in some ways, new—especially in the context of China—as it is the most densely concentrated area of “European-built projects” within mainland China in the early twentieth century. The “Century Clock” that I had walked past from the main train station makes one feel oriented toward an “old city.”

Many former villas throughout the Italian Style Area bear canvas awnings flapping in the wind saying, “Quartiere ItalianO” meaning “Italian Area.” (Fig. 24). Other moments, like the echo of Italian opera through former fences to a villa labeled “Italian Wonderland” allowed me to see what local tourists gravitated towards. But among what is “new” or European for tourists is also “old” and well protected. Often, some of the villas become the backdrop of tourist shops and restaurants (Fig. 25). Brass tiles inset into the pavers highlight facts about the area, in both Mandarin and English, along what seemed to be the most entertaining streets for local tourists based on the amount of people passing through. If there is not a singer on the mic in front of the restaurant Il Flamenco (Fig. 26), surely music by artist Bad Bunny may be blasting to lure tourists to the wide range of options to eat, including the Italian Venezia Club.

Fig. 27 – Zhongshuge Bookstore, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 28 – Building worker passing by advertising for a new Patina Hotel & Resort in the Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 29 – Tree through scaffolding of the renovating blocks in the Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Besides food-oriented tourist attractions, there was a striking contemporary intervention by a Shanghainese architecture and interior design office just last year. The Zhongshuge Bookstore (鍾書閣) by X+Living is a visually striking insertion into the historical area that quite literally ‘slices the classical’ (Fig. 27). The founder, Li Xiang, says the project “proclaims a definition; it also leaves room for gaps, inviting conflict and challenge to occur.” The building on the site of the new bookstore was supposedly “too modern” and “considered out of sync with the surrounding classical architecture” of the area. Most visitors seemed drawn not necessarily for the books, but for the building’s photogenic interior. After my time in China, it became evident that there is a strong appeal for distinctive spatial experiences tied closely to consumer culture.

Walking around the area near the new bookstore, I noticed prominent reconstruction and renovation efforts across various blocks. Yellow hard-hat construction workers moved along the streets alongside tourists. Among the fence-line advertisements outlining the district’s development direction, there was one promoting a luxury hotel called Patina (Fig. 28). While significant changes are underway, some things remain—like the tree-lined streets. The scaffolding on the facades under renovation allows trees to pierce through the metal shell, partially concealing the buildings under reconstruction (Fig. 29). I am eager to see how the area will evolve over the next few years as tourism increases with the attractions in the area.

Fig. 30 – Typical plaque designating “historic preservation and protection” of buildings in the Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 31 – Site of the former Chiesa del Sacro Cuore and Ospedale Civile Italiano at the edge of Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 32 –View from the arched corridors at the former Italian Barracks, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 33 –View from square between the Italian Barracks, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

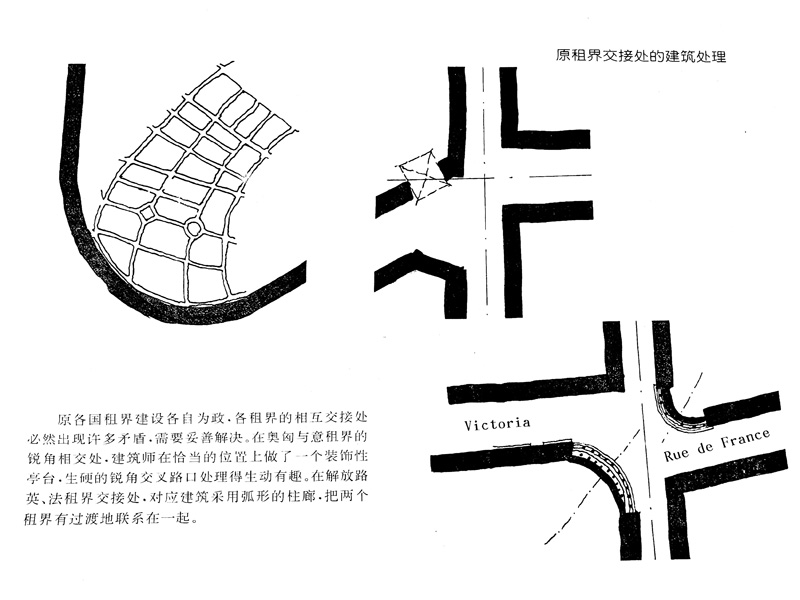

Various plaques sharing information on the area’s preservation efforts acknowledge the “Historical and Stylistic Architecture of Tianjin” (天津市历史风貌建筑) where a selection of buildings are given a grade of protection. The former ‘Chiesa del Sacro Cuore’ and ‘Ospedale Civile Italiano’ in front of what was previously called ‘Corso Vittorio Emanuele III’ are among those preserved buildings (Fig. 30). The building remains standing on a predominant street originally delineated by Genio Adolfo Cecchetti’s 1905 master plan. It is interesting to see the adaptation versus the preservation interventions including a ground floor entryopened for a below-ground transit hub (Fig. 31). After encountering façades preserved more for their unique historical character and craftsmanship, I moved on to a site where adaptive reuse was actively engaged—both materially and programmatically—in dialogue with the past.

I walked into the former Italian Barracks, originally named Caserma Ermanno Carlotto, where soldiers were stationed during the Italian occupation (Fig. 32). In 1932, “men of the San Marco Regiment” could be seen “performing gymnastic exercises” in the public square shaped by the building. Today, the building is filled with creative programs—artist studios, an Italian-style café, a yoga studio, and more. A small business opening onto the plaza across from a traditional tea shop is an “Italian-style store” called Bittersweetie (比她甜). And while anime posters now cover the towering scaffolding of this former barracks, there is clearly an intention to repurpose the public space without interfering with the original building (Fig. 33). Moving from this localized reuse of military space, the spatial narrative of the former Italian concession continues to unfold more prominently at its symbolic core—Marco Polo Square.

Fig. 34 –Marco Polo Square, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 35 – ‘Goddess’ Ice-cream sold around Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 36 – Schematic drawing of Italian Style Area, in ‘Tianjin Concessions Architecture (天津的建筑文化),’ Tianjin University Press, 1998 (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 37 – Image viewing Marco Polo Square in a corridor leading to the public space, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 38 – Image viewing Marco Polo Square and the former Forum building, Memory Exhibition, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 39 – 1998 Elevation drawing of the former Forum building, in ‘Tianjin Concessions Architecture (天津的建筑文化),’ Tianjin University Press (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 40 – Leaves re-ornament, in place of the axes, of the fasce on the former Forum building built under the Italian Fascist Regime, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

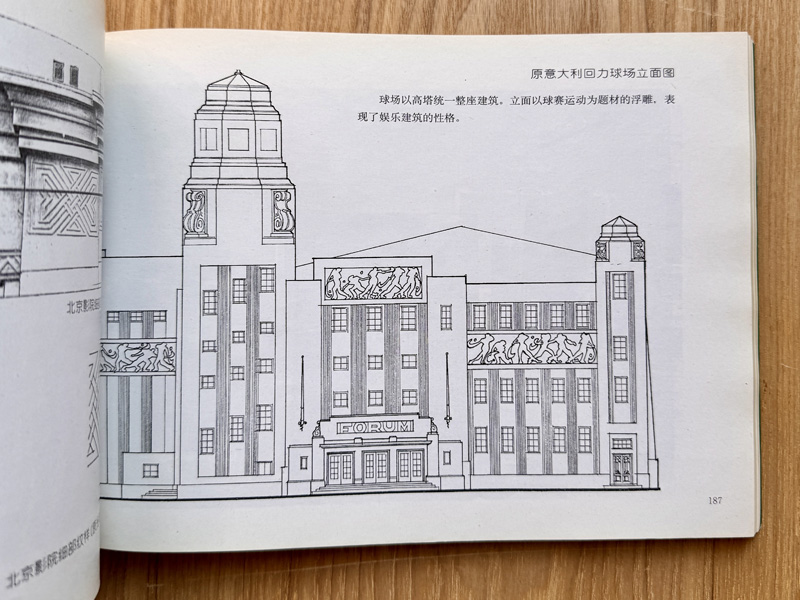

The central point in the district seems to gravitate towards Marco Polo Square (马可波罗广场) what was formerly called Piazza Regina Elena. As seen in an photographs from 1932, Piazza Regina Elena was a prominent ‘vehicular’ roundabout in the Italian concession. Now, it is strictly for pedestrians. According to archival film from 1935, this column can be seen and described as the “Monument of Victory” dedicated to Marco Polo, as it remains today (Fig. 34). At the center of the public square is a towering column that people refer to as the “Goddess of Peace.” This can be reinforced in tourist products like pins and even ice cream (Fig. 35). Together, Marco Polo Square and its counterpart, Dante Square, have remained intact since the concession period and retain their original planning intention (Fig. 36).

The "image of the [model] city" is evident in the corridor branching from Marco Polo Square beneath the artificial wisteria pergola marked “Anghiari,” which leads to the “boutique street” (Fig. 37). These visuals offered a useful contrast to the historic images shown earlier in the Memory exhibition, helping me perceive a commemorative relationship between the monument at the center of Marco Polo Square and the former Forum building (Fig. 38). A close-up of the tower anchoring the building to the public square clearly reveals the fasces symbols constructed during the fascist regime. As described by Istituto Luce in 1935, the Forum was considered “one of the most modern constructions of the Regime” in Tianjin. It is interesting to observe how the architectural details of the Forum have been recorded and modified over time. The textbook Tianjin Concessions Architecture (天津的建筑文化), published by Tianjin University Press in 1998, documents the sport-related reliefs I recognized from historical images. However, the fasces were illustrated as ornate scrolls (Fig. 39) in the textbook. Today, the fasces remain—at least the bundles of reeds—now re-ornamented with leaves rather than axes (Fig. 40).

This gesture of adaptation—preserving without fully erasing—can be seen throughout the district. One stair renovation, for example, reveals a striking contrast between restored stone balustrades on the left and an unfinished, patched brickwork section on the right, highlighting the blend of preservation and improvised repair (Fig. 41). Buildings across the area have become a backdrop for visible change, particularly around the former concession (Fig. 42). A Starbucks now faces Dante Square (Fig. 43/44), a move that might feel like adding insult to injury when considering Italy’s deeply rooted coffee culture. Meanwhile, the ever-expanding skyline along the riverfront tells a parallel story of growth and reinvention (Fig. 45) of Tianjin around its concessions.

Fig. 41 – Moments of preservation and adaptation, balustrade in Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 42 – Mass of city bikes scattered at the edges of the Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 43 – Advertising for the Starbucks at Dante Square, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 44 – Sea of rickshaws around Dante Square, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 45 – View across the Haihe River from the former riverbank of the Italian concession, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 46 – View walking away from the former Italian Barracks, Italian Style Area, Tianjin, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Although scholars have critiqued the touristification of the Italian concession, the term “Disneyfication” seems overcasted to describe how the area has been transformed into a space for entertainment—one increasingly detached from its imperial past, yet visibly there. Similar transformations are evident in the British and French concessions, which now serve primarily as sites of leisure and consumption. I found this version of history—not erased but theatrically softened—both humorous and thought-provoking. It reminded me of the “Little Italy” or “Chinatowns” across the U.S., where heritage is repackaged into a consumable form. Yet what’s happening in Tianjin is notable: rather than demolish the past, the municipality has chosen to preserve and rebrand it, cleverly repurposing the area for domestic tourism. In doing so, Tianjin positions itself as a “model” Europeanized city—one that makes Europe “local” to China.

Looking beyond the twentieth-century past and into the current skyline (Fig. 47), it’s clear that China’s building sector is advancing at an overwhelming pace—something I also sensed during my time in Shanghai. I was continually impressed by the built environment, the efficiency of mass transit, and the vast cuisine. Each day offered reminders of the country’s dynamic qualities that I saw in the metropoles. I left China deeply inspired by the design work and filled with a renewed sense of anticipation for the future of architecture including from various adaptive reuse projects. I am genuinely looking forward to seeing how the cities I visited will continue to evolve—a momentum that left many of my daily questions about architectural history and memory trailing behind like dust.

Around Liguria and Genoa, Italy [Genova, Italia]

Fig. 47 – Via Angelo Olivieri, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

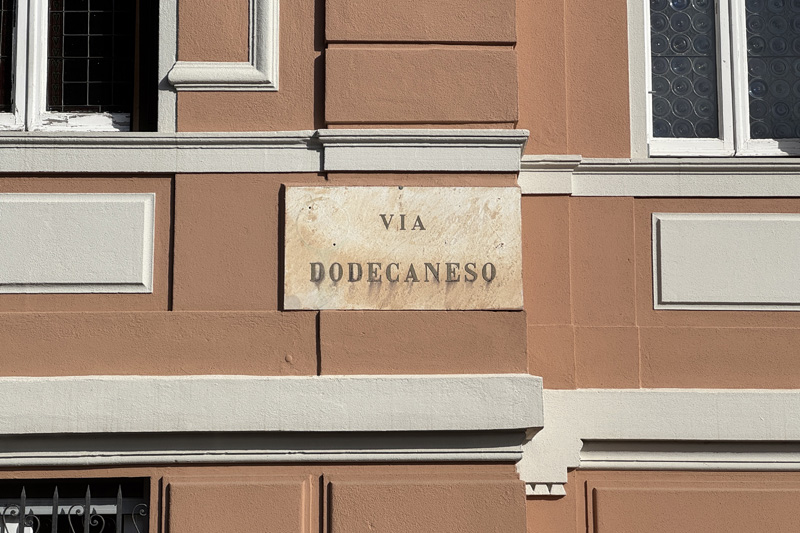

Fig. 48 – Via Dodecaneso, Genova, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 49 – Typical belvedere from the early twentieth century, seen along Via Dodecaneso, Genova, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 50 – Gated homes lined with Cyprus seen along Via Cirenaica, Genova, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 51 –Via Cirenaica street sign, Genova, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

I returned to Italy to visit the seaport of Genova. There, I once again found myself tracing various street names. Having just come back from China, I looked with attention to anything related to China—and unexpectedly, to Libya. After a short hike from a local bus stop, I arrived at Via Angelo Olivieri, a street named in honor of a “Medaglia d’Oro Ligure 1918.” In a book titled The Military Operations Overseas: The Gold Medal of Honor from 1871 to 1914, Angelo Olivieri is described as a “brave Italian naval officer born in Genoa in 1878.” He joined the Naval Academy in 1893 and served in China during the Boxer Rebellion, where he “defended the Italian legation in Beijing.” Later in his career, he served in the Italo-Turkish War in Libya and in World War I, during which he received the medal commemorated in this honorary street name. Seeing how far this name reaches outside the city of Genova, I reflected on how Italy’s overseas “wars” are often forgotten, miscontextualized, or make the “other” invisible.

This is also the case with Via Dodecaneso, located on the eastern side of Genova near the Università di Genova and the Fort of San Martino (Fig. 48). The street name refers to the Dodecanese Islands, which, like Libya, were occupied by Italy as part of its imperial ambitions during and after the Italo-Turkish War. As I walked around, I noticed residential homes—spacious villas, landscaped and fenced. I saw a familiar form, one that reminded me of the buildings that visually define Marco Polo Square in Tianjin (Fig. 49). The villa in Genova and the buildings around Marco Polo Square share architectural forms built in the early twentieth century. This neoclassical details—particularly the belvedere towers and stucco façades—reflects how Italian architectural aesthetics were expressed both domestically and abroad. As I walked further into the neighborhood, I came across more villas, palaces, and generously landscaped residential blocks around familiar names (Fig. 50). I passed Via Cirenaica (Fig. 51), before arriving at Via Eritrea and Via Somalia. As in Turin, these clusters of names referencing formerly occupied territories now sit devoid of context. The places that once bore the weight and trauma of occupation are now embedded in lush neighborhoods, stripped of their meaning—beyond, perhaps, their original intent: pride in possession.

Not far from Genova, in the small picturesque towns along the Ligurian coast, similar traces appear—including Via Tripoli, Via Dogali, and Via Somalia in the seaside town of Santa Margherita (Fig. 52). Although these places never reached the population scale of the metropols of their time, monumental gestures enacted under the fascist regime remain inscribed, with flagpoles still standing (Fig. 53). Imperialism lingers (Fig. 54), even unintentionally, as remnants remain embedded in infrastructure. Among the three Christopher Columbus monuments in Genova, Rapallo, and Santa Margherita (Fig. 55), the pride once invested in these symbols has shifted, as Italy’s national history—and its colonial legacy—has come under renewed critique.

Fig. 52 –Via Tripoli street sign, Santa Margharita, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 53 –Flagpole pedestal along lungomare, Santa Margherita, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 54 –Imperiale Palace Hotel signage between Rapallo and Santa Margherita, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 55 –Christopher Columbus monument, Santa Margherita, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 56 –Piazza della Vittoria, Genova, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 57 –A monumental view of Piazza della Vittoria, Genova, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

This evolving perception became even more tangible as I returned to Genova’s urban core, where the city’s architectural memory revealed further echoes of past ideologies. As I continued my walks through Genova, I began to notice parallels to my previous travels. While walking around Piazza della Vittoria, I encountered yet another flagpole pedestal—a monument to an unraised flag (Fig. 56). The covered colonnades, rational in their form, reminded me of similar fascist-era interventions I had seen earlier that month in Parma (Fig. 57). These buildings—urban markers of a bygone era—were constructed to instill patriotic sentiment where they stood.

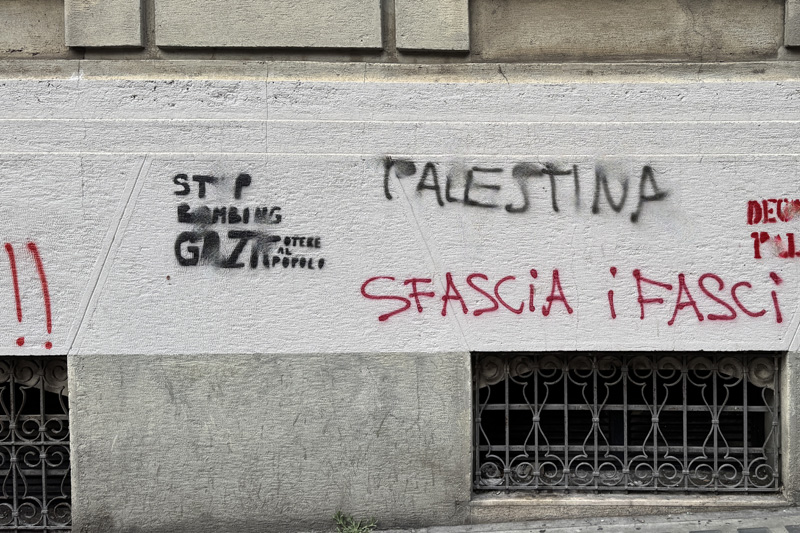

Over time, however, I was reminded that the remnants of Italy’s fascist era continue to be actively resisted and rejected. In passing Piazza Giacomo Matteotti, I saw written on palazzo walls the words “Sfascia i fasci” meaning “break the reeds,” or symbolically, “break down fascism” (Fig. 58). Throughout Genova’s, at least in some neighborhoods, anti-fascist memory is proudly visible, especially in April, when nearly every storefront displays signs with the tricolore, “W il 25 Aprile” (Fig. 59). April 25th, a national holiday, commemorates Italy’s “Liberation” and honors the uprising of the Partigiani, or partisans. It is also a day to remember the Italian Resistance against Nazi Germany and the Italian Social Republic otherwise known as the Fascist Regime. What remains largely dismissed, however, is Italy’s colonial legacy and anti-colonial resistance—overshadowed by narratives of partisan resistance and postwar reconstruction, and left unexamined in many of the very spaces it once sought to define.

Fig. 58 –“Sfascia I fasci” seen on the walls of downtown Genova, Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Fig. 59 –“W il 25 Aprile” in celebration of the upcoming “Liberation Day,” Liguria, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)

Invisible Cities, La Città Invisibili, [看不见的城市]

In reflection of Genova, Turin, and Tianjin, I am reminded of a passage from Italo Calvino’s Le città invisibili (1972), which I came across from a translated copy, 看不见的城市, in Shanghai (Fig. 60). During my travels, I wandered into a Japanese chain bookstore—Tsutaya Books—located in the renovated “American Columbia Country Club” (c. 1928), originally designed by László Hudec. Supposedly, during the Japanese occupation of Shanghai at the height of WWII, this now-commercial complex at Columbia Circle was the site of an internment camp for “allied civilians” from 1943 to 1945. Columbia Circle area was one of several internment camps in the city that existed at the same time as the mass internment of Japanese-Americans across the United States. The camps as a spatial device—historical and remembered—have lingered somehow throughout my travel reflections, as it did in Turin. The links between histories of internment, camps, and patterns of settlement are deeply intertwined with the very act of understanding the built environment—an idea that Calvino captures through his impressions of buildings through language.

Every time I return to Calvino’s ‘Invisible Cities,’ I reread the final chapter. He makes it clear that the cities Marco Polo describes to Kublai Khan are not real—they are imagined constructs. “I should not tell you of Berenice, the unjust city,” Polo begins, and, “from my words you will have reached the conclusion that the real Berenice is a temporal succession of different cities, alternately just and unjust. But what I wanted to warn you about is something else: all the future Berenices are already present in this instant, wrapped one within the other, confined, crammed, inextricable.” In reading this fiction, my knowledge of Italy’s occupation of Cyrenaica resurfaces—particularly how the name "Berenice" was re-materialized even in the name of the grand theatre in “Italian-colonial” Benghazi. For me, Calvino’s "Berenice" echoes the life cycle of modern-day Benghazi itself. Both the “just” and “unjust” city persist, enduring an entanglement with forces—both historical and ongoing—that remain unresolved and to be reckoned with.

As I continue my travel—having been through Italy, through China—I hope to reflect not only on the buildings I admire and question, nor merely on the language and materials that shape them, but to seek out the deeper, layered meanings of other “invisible cities” along the way.

Fig. 60 –Translated copy of Italo Calvino’s ‘Invisible Cities’, Shanghai, China (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, April 2025)