-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

On Teaching, Traveling, and Learning: Brooks Fellowship Summary

Jul 13, 2015

by

Amber N. Wiley, 2013 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow

When I began my teaching career at the Tulane School of Architecture I had a specific challenge ahead of me: re-fashioning a course entitled “History of Architecture: Ancient to Medieval” that previously centered on the Western tradition to one that had a global focus. This meant including more sites outside Europe: those found in Central and South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia. Suddenly the textbooks I was most familiar with, from surveys in undergrad and pursuing my masters, would not suffice. My first hurdle was to find the literature that would work for such a major undertaking. I searched for online course syllabi that dealt with the same topics and time span, reviewed their readings, and created my own patchwork of readings from various publications. Even after giving myself the proper framework (in the form of course readings) to begin to talk about a global history of architecture I still had to think about organization—would it regional or thematic? Chronological or based on common climates? In the end I divided the course into two sections: Western and non-Western. I was not satisfied with the decision, but it was useful for practical purposes.

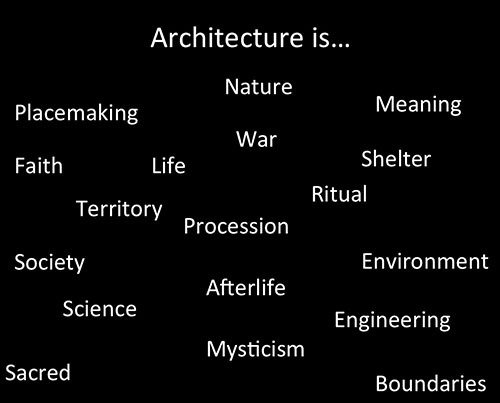

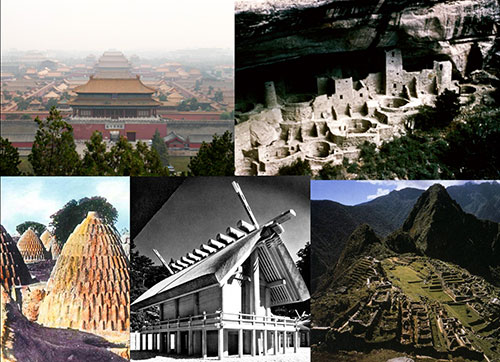

The course transformed again the second time I taught it, to become “History and Theory of Architecture and Urbanism I: World Architecture to the Enlightenment (Global Settlements).” Yes, I realize the length of the title was unconscionable. I shortened the subtitle the third year I taught the course, dropping “to the Enlightenment,” the only hint at a time frame. Certain aspects of the course were growing clearer, even as the course title became more vague. I adopted three texts that would inform my new way of thinking about the course. These texts would also inform the itinerary I created when submitting an application for the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. The texts were Richard Ingersoll and Spiro Kostof, World Architecture: A Cross-Cultural History, Dora P. Crouch and June G. Johnson, Traditions in Architecture: Africa, America, Asia, and Oceania, and Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. I wanted several themes to come to the fore in my teaching. First, that we (as a class) were examining the built environment on a variety of scales, from individual buildings to patterns of settlement, and then looking at the relationship of the settlements to the surrounding landscape. Central to our architectural analysis was how different cultures and communities made meaning in their everyday lives through design, discussion on what architecture reveals about societal concerns and hierarchies, and the ways in which natural settings are exploited for sustenance and protection.

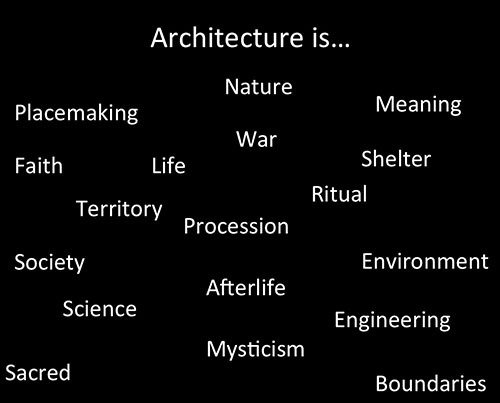

Figure 1. Slide from introduction lecture in “History and Theory of Architecture and Urbanism I.”

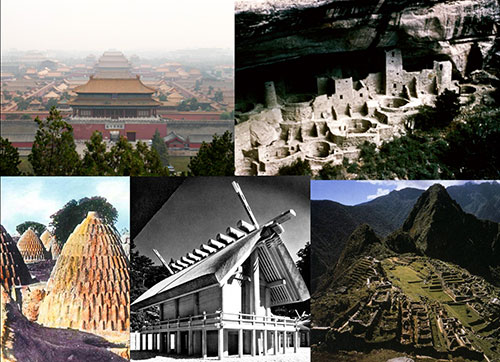

Figure 2. Another slide from the course introduction lecture.

These ideas underlined the creation of my itinerary and the various aspects of design that I would investigate over the course of a year with the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. I selected sites that were not a part of the Western canon. The sites I visited are in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, specifically Mexico, Guatemala, Ghana, Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam. I wanted to see not only the ways that communities create, inhabit, and think about space, but what these interactions reveal about the society in which the space is produced. As a result, while I gained a greater understanding of individual structures, cities, and landscapes themselves, I also thought deeply about the intersections of culture, geography, design, preservation, and public history. The places I visited have complicated histories, and are located in countries that face a variety of challenges. Public history and preservation practices have to acknowledge strong indigenous cultural traditions and reconcile a colonial past with a post-colonial present. Additionally, these sites and cities struggle with political corruption and/or instability, and, in some cases, burgeoning populations and a high premium for real estate in historically significant areas.

These themes came up time and again in my blog entries, as well as many of the readings I chose to highlight in the blog. Every country I visited was considered “Third World” in the traditional sense of the word. The desire to classify these countries persists, and most of them now fall under the banner of the “Global South.”1 The terms Third World and Global South, while both contested and fluid, do evoke very specific negative connotations: those of poverty, heavy industrialization, pollution, public health crises, and overpopulation. The term Global South, however, seems to be a rebranding and repositioning tool that allows for more positive connotations as well. I have found many scholars of the Global South describing urban conglomerations such as Mumbai as cities of the future, with emergent economies. As political alignments have shifted, and as economies have diversified from agricultural and industrial-based, some of these countries no longer fit in that outdated mode of Third World categorization: Mexico and India are prime examples. All of these issues put pressure on the tourism industry. They also inform how historic preservation works and how culture—as a quantifiable and tangible product—is constructed. These are some of the issues that added richness and complexity to my investigation of specific sites throughout the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

In addition to learning about the world and seeing sites firsthand, my time abroad also forced me to learn new technologies (or at least technologies that were new to me) and think about how I would deliver my thoughts and experiences to a wider audience. The fellowship required that I upload images to SAHARA, so automatically I was adding to the SAH commitment to the digital humanities.2 I also worked with Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, Galileo Offline Maps, Google Maps, Instagram, Wordpress, and Prezi. Lightroom allowed me to edit and organize photos en masse, Galileo was great for navigating each city and town, Google Maps for recording the various sites and cities I visited, Instagram for keeping me engaged in daily photographic documentation via my iPhone, and Wordpress for my personal blog.

Although I had learned about Prezi several years ago while serving as a teaching fellow at the Center for Engaged Learning and Teaching at Tulane, I only began working with the platform after my trip was finished. Prezi offers free account services for educators and students, so I signed up to teach myself how to use the presentation platform. I visited my 11-year-old niece in South Korea at the end of my trip and I wanted her to understand the trajectory and geography of my travels. I thought a regular PowerPoint would not do, and found a World Geography template through Prezi that was perfect for my purposes. The first Prezi I created was entitled “2014–2015: Auntie Amber’s Travels.” While I do not intend to rely solely on this tool for teaching (I do prefer PowerPoint), after my initial experience with it I can easily imagine using both Prezi and PowerPoint throughout the school year, as needed.

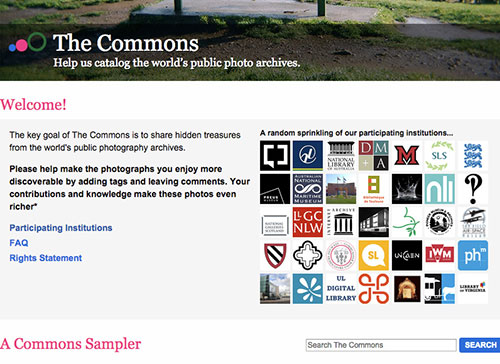

Another venture into digital humanities during my travels was my reliance on databases such as the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs online collection, Flickr: The Commons, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture for historical photographs and maps of the sites I visited. This allowed me to acquire digital images in the public domain from a wealth of archives such as the LOC, CCA, the British Library, Internet Archive Book Images, the Cornell University Library, the National Archives UK, the New York Public Library, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Nationaal Archief to supplement my understanding of the history of the sites and cities. Many historical images I used in the blog, from cities as distant as Antigua, Delhi, and Hanoi, were from these online sources.

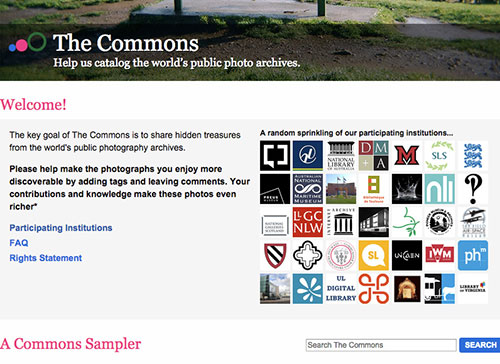

Figure 3. Screen capture of Flickr: The Commons and a few of the archives included in the online image collection.

Moving forward, my immediate plans after the fellowship include readjustment back to the States, taking care of various writing projects and deadlines, board duties for two organizations, as well as seeing friends and family after a year absence. I will begin a new position as assistant professor of American studies at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York. I teach two courses in the fall, “Introduction to American Studies: The American City,” and “Themes in American Culture: African-American Experience.” While my early background is strictly architecture—undergraduate degree in architecture, master’s in architectural history—my doctorate is in American studies. My specializations within the field are architectural history, urban history, and African-American cultural studies. My research interests focus on the built environment, but expand beyond that to take into consideration social issues that relate to design. I often joke that I am a “Professor of Place.” The travel that I completed over the course of this year has significantly impacted not only my understanding of architectural sites across the world, but also my understanding of the particularities of place. New understandings of place and ways to talk about our lived experiences within spaces will inform how I teach my fall courses. Teaching is a creative endeavor, and my experiences have sharpened my ability to make cross-disciplinary connections in the examination of place. Therefore my “American City” course provides snapshots of the nation’s history through an investigation of communal and urban sites. Topics include pre-colonial beginnings, European colonies, the new nation, westward expansion, the industrial city, changing technologies, changes in urban social and spatial structure, urban politics, migration and immigration, and suburbanization. Meanwhile, my “African-American Experience” course pays particular attention to migratory patterns of African-Americans within and outside of the United States. This consideration illustrates how industry, war, social segregation, international diplomacy, and family ties helped shape the relationship between the rural and urban African-American experiences.

Figure 4. Illustrations on my fall course syllabi. Top illustration is for the “American City” course with Daniel Burnham’s plan for Chicago. Bottom illustration is for the “African-American Experience” course with Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series.

Figure 5. Seeing the U.S. with new eyes: exploring the Film Exchange District in downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Just recently a friend of mine commented on an Instagram picture I posted while visiting family in Oklahoma City. I was exploring the major changes happening downtown. I walked around the Film Exchange District, a historic section that focuses on art production and celebrates various western architecture and art deco motifs in the area through ongoing preservation efforts. The picture I posted was a reflection of a store window that captured items for sale as well as Devon Tower, a symbol of the emergent skyline that is a result of a booming energy economy in the state. The friend exclaimed, “I love that you're continuing to wander and take pictures and think like your trip hasn't ended. Maybe that's the key!” I am seeing everything with fresh eyes—including places I know well, like my hometown of Oklahoma City. These fresh eyes will help me be a better researcher, writer, and a professor. In fact, that is the key.

The course transformed again the second time I taught it, to become “History and Theory of Architecture and Urbanism I: World Architecture to the Enlightenment (Global Settlements).” Yes, I realize the length of the title was unconscionable. I shortened the subtitle the third year I taught the course, dropping “to the Enlightenment,” the only hint at a time frame. Certain aspects of the course were growing clearer, even as the course title became more vague. I adopted three texts that would inform my new way of thinking about the course. These texts would also inform the itinerary I created when submitting an application for the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. The texts were Richard Ingersoll and Spiro Kostof, World Architecture: A Cross-Cultural History, Dora P. Crouch and June G. Johnson, Traditions in Architecture: Africa, America, Asia, and Oceania, and Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. I wanted several themes to come to the fore in my teaching. First, that we (as a class) were examining the built environment on a variety of scales, from individual buildings to patterns of settlement, and then looking at the relationship of the settlements to the surrounding landscape. Central to our architectural analysis was how different cultures and communities made meaning in their everyday lives through design, discussion on what architecture reveals about societal concerns and hierarchies, and the ways in which natural settings are exploited for sustenance and protection.

Figure 1. Slide from introduction lecture in “History and Theory of Architecture and Urbanism I.”

Figure 2. Another slide from the course introduction lecture.

These ideas underlined the creation of my itinerary and the various aspects of design that I would investigate over the course of a year with the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. I selected sites that were not a part of the Western canon. The sites I visited are in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, specifically Mexico, Guatemala, Ghana, Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam. I wanted to see not only the ways that communities create, inhabit, and think about space, but what these interactions reveal about the society in which the space is produced. As a result, while I gained a greater understanding of individual structures, cities, and landscapes themselves, I also thought deeply about the intersections of culture, geography, design, preservation, and public history. The places I visited have complicated histories, and are located in countries that face a variety of challenges. Public history and preservation practices have to acknowledge strong indigenous cultural traditions and reconcile a colonial past with a post-colonial present. Additionally, these sites and cities struggle with political corruption and/or instability, and, in some cases, burgeoning populations and a high premium for real estate in historically significant areas.

These themes came up time and again in my blog entries, as well as many of the readings I chose to highlight in the blog. Every country I visited was considered “Third World” in the traditional sense of the word. The desire to classify these countries persists, and most of them now fall under the banner of the “Global South.”1 The terms Third World and Global South, while both contested and fluid, do evoke very specific negative connotations: those of poverty, heavy industrialization, pollution, public health crises, and overpopulation. The term Global South, however, seems to be a rebranding and repositioning tool that allows for more positive connotations as well. I have found many scholars of the Global South describing urban conglomerations such as Mumbai as cities of the future, with emergent economies. As political alignments have shifted, and as economies have diversified from agricultural and industrial-based, some of these countries no longer fit in that outdated mode of Third World categorization: Mexico and India are prime examples. All of these issues put pressure on the tourism industry. They also inform how historic preservation works and how culture—as a quantifiable and tangible product—is constructed. These are some of the issues that added richness and complexity to my investigation of specific sites throughout the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

In addition to learning about the world and seeing sites firsthand, my time abroad also forced me to learn new technologies (or at least technologies that were new to me) and think about how I would deliver my thoughts and experiences to a wider audience. The fellowship required that I upload images to SAHARA, so automatically I was adding to the SAH commitment to the digital humanities.2 I also worked with Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, Galileo Offline Maps, Google Maps, Instagram, Wordpress, and Prezi. Lightroom allowed me to edit and organize photos en masse, Galileo was great for navigating each city and town, Google Maps for recording the various sites and cities I visited, Instagram for keeping me engaged in daily photographic documentation via my iPhone, and Wordpress for my personal blog.

Although I had learned about Prezi several years ago while serving as a teaching fellow at the Center for Engaged Learning and Teaching at Tulane, I only began working with the platform after my trip was finished. Prezi offers free account services for educators and students, so I signed up to teach myself how to use the presentation platform. I visited my 11-year-old niece in South Korea at the end of my trip and I wanted her to understand the trajectory and geography of my travels. I thought a regular PowerPoint would not do, and found a World Geography template through Prezi that was perfect for my purposes. The first Prezi I created was entitled “2014–2015: Auntie Amber’s Travels.” While I do not intend to rely solely on this tool for teaching (I do prefer PowerPoint), after my initial experience with it I can easily imagine using both Prezi and PowerPoint throughout the school year, as needed.

Another venture into digital humanities during my travels was my reliance on databases such as the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs online collection, Flickr: The Commons, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture for historical photographs and maps of the sites I visited. This allowed me to acquire digital images in the public domain from a wealth of archives such as the LOC, CCA, the British Library, Internet Archive Book Images, the Cornell University Library, the National Archives UK, the New York Public Library, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Nationaal Archief to supplement my understanding of the history of the sites and cities. Many historical images I used in the blog, from cities as distant as Antigua, Delhi, and Hanoi, were from these online sources.

Figure 3. Screen capture of Flickr: The Commons and a few of the archives included in the online image collection.

Moving forward, my immediate plans after the fellowship include readjustment back to the States, taking care of various writing projects and deadlines, board duties for two organizations, as well as seeing friends and family after a year absence. I will begin a new position as assistant professor of American studies at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York. I teach two courses in the fall, “Introduction to American Studies: The American City,” and “Themes in American Culture: African-American Experience.” While my early background is strictly architecture—undergraduate degree in architecture, master’s in architectural history—my doctorate is in American studies. My specializations within the field are architectural history, urban history, and African-American cultural studies. My research interests focus on the built environment, but expand beyond that to take into consideration social issues that relate to design. I often joke that I am a “Professor of Place.” The travel that I completed over the course of this year has significantly impacted not only my understanding of architectural sites across the world, but also my understanding of the particularities of place. New understandings of place and ways to talk about our lived experiences within spaces will inform how I teach my fall courses. Teaching is a creative endeavor, and my experiences have sharpened my ability to make cross-disciplinary connections in the examination of place. Therefore my “American City” course provides snapshots of the nation’s history through an investigation of communal and urban sites. Topics include pre-colonial beginnings, European colonies, the new nation, westward expansion, the industrial city, changing technologies, changes in urban social and spatial structure, urban politics, migration and immigration, and suburbanization. Meanwhile, my “African-American Experience” course pays particular attention to migratory patterns of African-Americans within and outside of the United States. This consideration illustrates how industry, war, social segregation, international diplomacy, and family ties helped shape the relationship between the rural and urban African-American experiences.

Figure 4. Illustrations on my fall course syllabi. Top illustration is for the “American City” course with Daniel Burnham’s plan for Chicago. Bottom illustration is for the “African-American Experience” course with Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series.

Figure 5. Seeing the U.S. with new eyes: exploring the Film Exchange District in downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Just recently a friend of mine commented on an Instagram picture I posted while visiting family in Oklahoma City. I was exploring the major changes happening downtown. I walked around the Film Exchange District, a historic section that focuses on art production and celebrates various western architecture and art deco motifs in the area through ongoing preservation efforts. The picture I posted was a reflection of a store window that captured items for sale as well as Devon Tower, a symbol of the emergent skyline that is a result of a booming energy economy in the state. The friend exclaimed, “I love that you're continuing to wander and take pictures and think like your trip hasn't ended. Maybe that's the key!” I am seeing everything with fresh eyes—including places I know well, like my hometown of Oklahoma City. These fresh eyes will help me be a better researcher, writer, and a professor. In fact, that is the key.

- See Martin W. Lewis, “There Is No Third World; There Is No Global South,” GeoCurrents November 15, 2010 Dayo Olopade, “The End of the ‘Developing World,’” New York Times February 28, 2014; Marc Silver, “If You Shouldn't Call It The Third World, What Should You Call It?” NPR January 4, 2015

- See Dianne Harris, “Learned Society 2.0,” SAH Blog September 1, 2011