-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Back to the Balkans (and then the States): Final Report

I write this in Prizren, Kosovo, during the one of the last legs of my travels. Now that my tenure as H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow comes to an end, it is time to reflect on a year that has been, in many ways, extraordinary. The chance offered by the fellowship to explore, travel without haste, and without the limitations of specific sites indicated in a research proposal is profoundly enriching and transformative. Over the course of the year, I travelled to (in alphabetical order): Armenia, Bosnia, Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Israel, Kosovo, Lebanon, Macedonia, Morocco, Spain, Turkey, and the UK. While this itinerary includes some conference travel that I would have undertaken in any case, much of it was thanks to the freedom afforded by the Brooks Fellowship, and the opportunity to spend several weeks or months in some of these places certainly was exceedingly valuable. Moreover, writing the monthly blog posts was a welcome break from my usual, academic writing that continued over the course of the fellowship year. The liberty of the format, as well as the possibility to write about sites that are not at the center of my research agenda, was refreshing in that it allowed me to develop an non-academic author’s voice, connected to but in large parts separate from my scholarly work. I am not sure how to continue with this type of writing, but would certainly like to do so as I continue my career as a scholar and teacher.

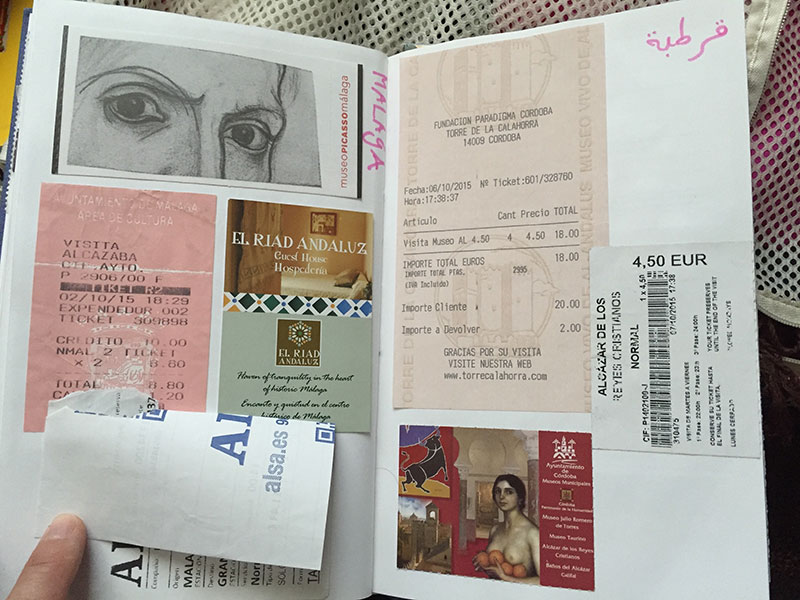

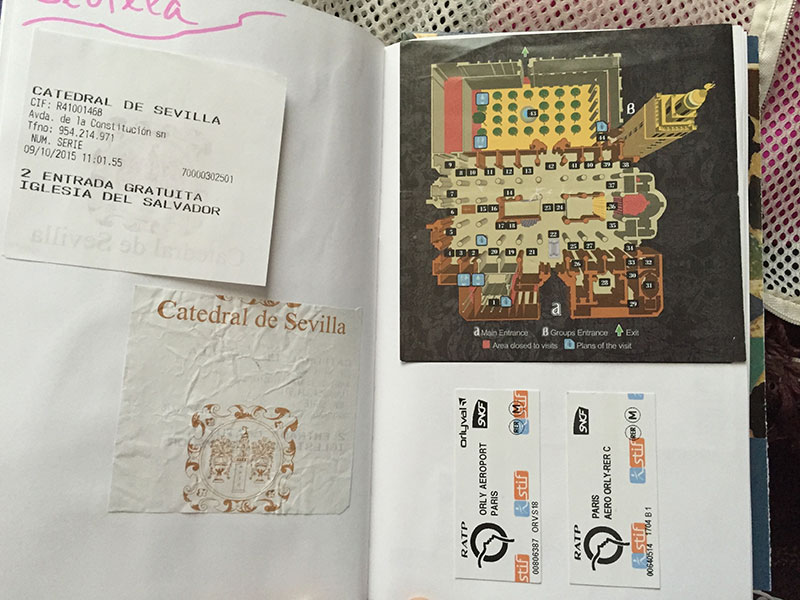

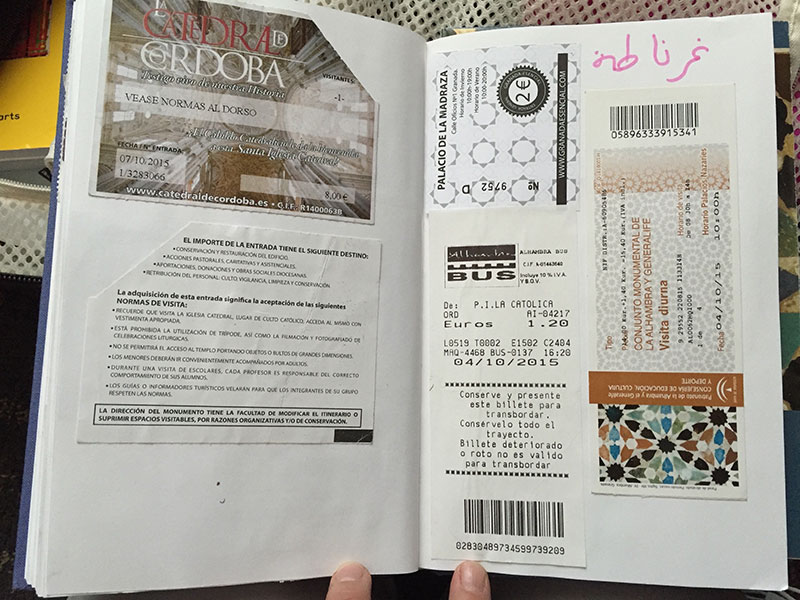

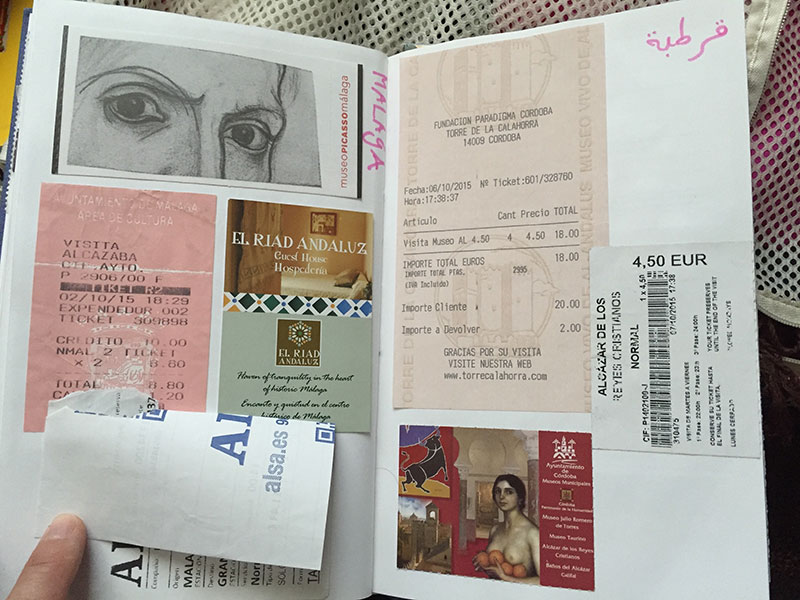

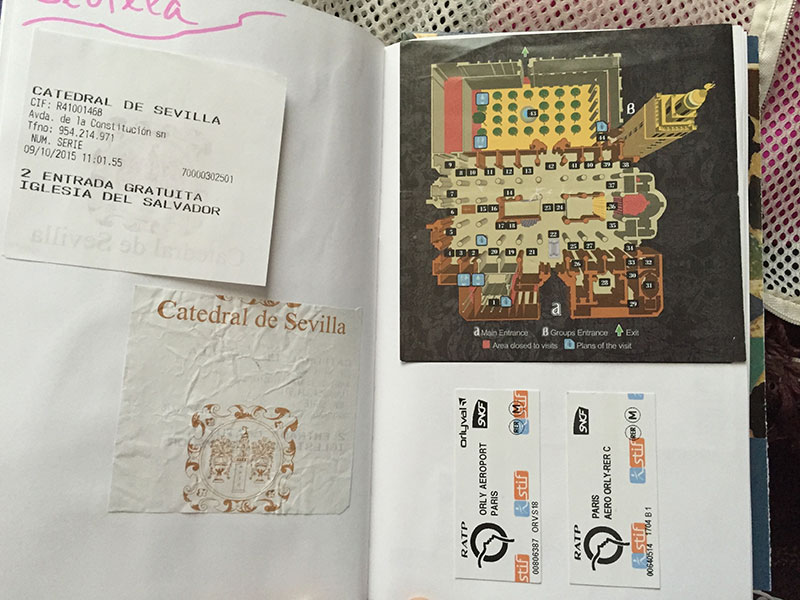

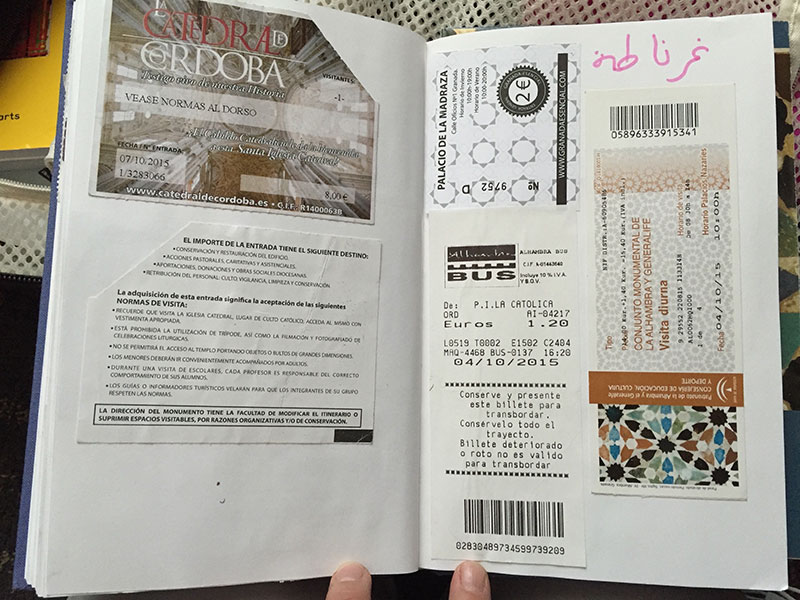

From the latter point of view, the Brooks Fellowship came at a crucial time in my career. It allowed me to develop new ideas for my research projects, to gather materials for teaching, but also to see monuments and cities that I had not been previously able to visit. As I wrote in my blog post in June, Jerusalem is one such example—a city that has played a central role in my studies since my first art history class as an undergraduate, but that was never before on my travel schedule. Similarly, Split, Sarajevo, Dubrovnik (blame Game of Thrones for that last one) are cities that I would have loved to see, without having a chance to do so because they are not part of my research portfolio, and hence not destinations that I could find funding for, or justify the expense of personal funds. In terms of advancing my research, I was able to add sites to my project on fifteenth-century Ottoman architecture while in Turkey, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedonia. Museum research for my ongoing book project on the materiality of architecture in medieval Spain was also part of this year, especially as being based in Europe allowed me to visit collections without the major logistics involved in cross-Atlantic travel. In addition to these more targeted visits, materials gathered in my scrap-books and notebooks will be previous resources as I return to the United States and will continue to process much of what I experienced (Figures 1–4).

Figures 1–4: random pages from one of my scrap-books.

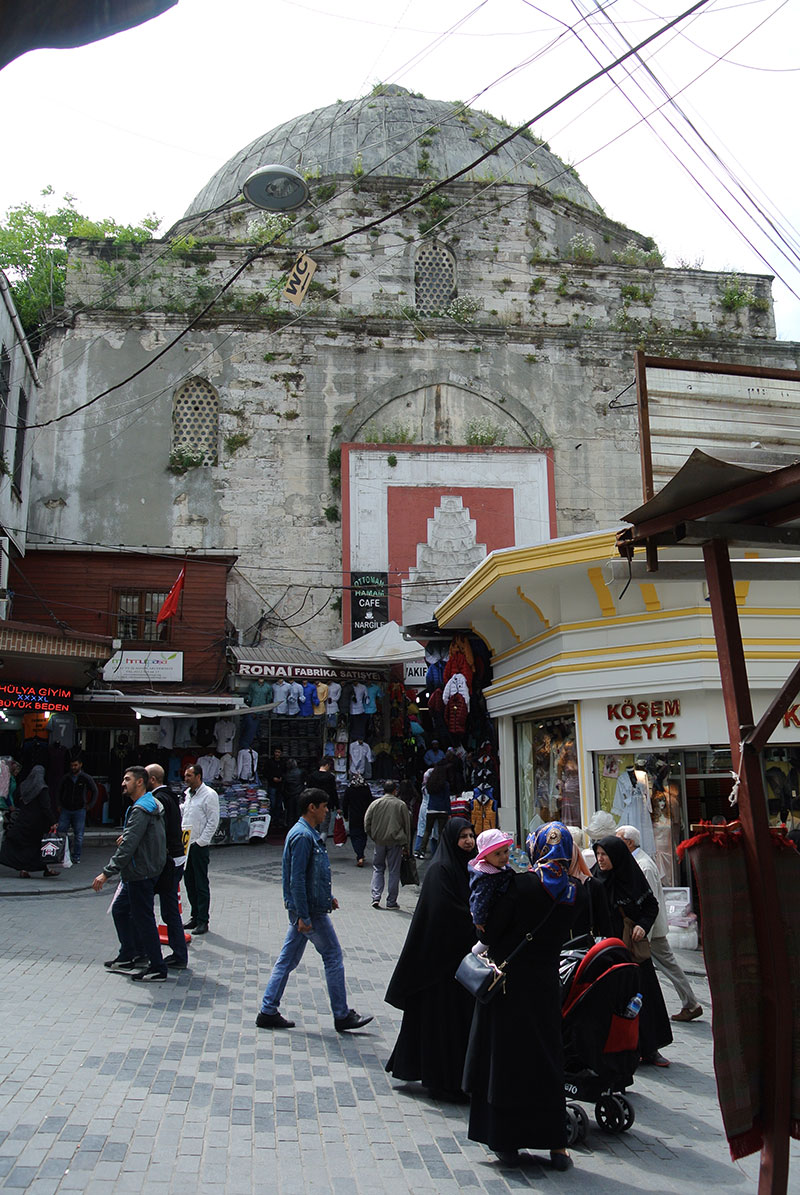

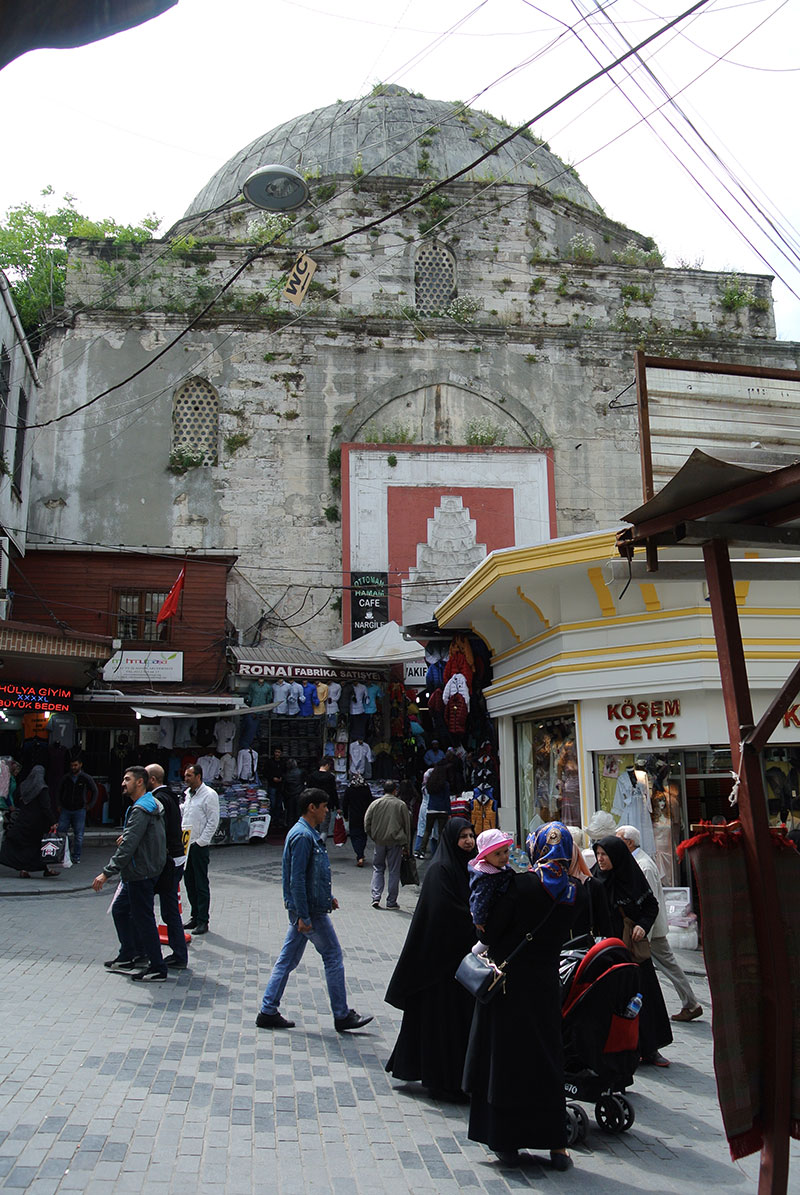

As I prepare the course that I will teach as visiting assistant professor of medieval Mediterranean art history at Pomona College next academic year, the pedagogical uses of my travels become clear. I will be able to include photographs from nearly all the sites I visited in course that cover medieval art and architecture in southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Again Jerusalem will be important, but also Istanbul, Bursa, Marrakesh, Fes, Ravenna, Rome, Malaga, Granada and Cordoba—along with Cairo, Damascus, Samarqand and other major cities in the Mediterranean and the Islamic world. Spending more time in Istanbul—the longest period of time I have been able to remain in the city since my dissertation research—allowed me to revisit many sites and to discover new ones. On the one hand, I was able to photograph buildings such as the Mahmud Pasha Hamam (Figures 5 and 6), built soon after the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul by one of Mehmed the Conqueror’s grand-viziers, or the seventeenth-century Valide Han (Figure 7). Both buildings are part of the maze of streets, full of historical entrepots and other monuments that developed around the Grand Bazar.

Figures 5 and 6: Mahmud Pasha Hamam, Istanbul (P. Blessing)

Figure 7: Courtyard of Büyük Valide Han, Istanbul (P. Blessing)

Similarly, museums that I was able to visit will play a central role in my research and teaching. Some collections, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the David Collection in Copenhagen, and the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid (Figures 8 and 9) have objects that are crucial for my second book, Monuments of Malleability: Illusion, Allusion, and Artifice in Islamic Architecture. At the same time, I was also able to see the collections of Islamic art in several museums, some of which are described in my December post, including several new installations that were opened in the last few years. This was a useful exercise in reflecting about Islamic art as a field of study, its public presentation in a museum setting, but also ways of introducing students to this subject in the classroom. The final result will only become apparent as I redesign my undergraduate survey lecture course on Islamic art in spring 2017, but I can anticipate how the narratives introduced in several museums will have an impact on my teaching. Out of other exhibitions that I saw, Fabric of India at the Victoria and Albert Museum was my favorite with its exhibits ranging from artifacts and videos related to textile production, to historical textiles and the work of contemporary Indian designers. I also enjoyed visiting collections that are not directly related to my research, such as the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen (Figure 10).

Figures 8 and 9: Instituto Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid (P. Blessing)

Figure 10: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark (P. Blessing)

Traveling in this day and age depends of course—sadly to some extent—largely on airplanes, I tried to use overland travel as much as possible. This worked well for my Italy and Balkans trip that involved trains (thanks to the excellent website The Man In Seat Sixty-One), ferries and buses. I was also able to use trains in Morocco, France, Germany, Spain, the UK, and Israel. This was not always the fastest way, but allowed me to see landscapes that I would have missed from the plane, apart from removing the stress of airport security. Still, many of the movements between countries happen in the air, showing both the ugliness of urban development on the coastal section of Beirut, and the beauty of the Alps on a flight between Zurich and Munich on the way to Washington, D.C., for the College Art Association Conference. Landscapes that fascinated me on the way ranged widely. Up front was certainly the Caucasian terrain vague on a mountain pass on the way to Lake Sevan in Armenia, where the fourteenth-century Selim Caravanserai gives reason to pause as to how one would possibly get up here with a medieval trade caravan (Figures 11 and 12). The drive from Sarajevo to Mostar was another memorable landscape (Figure 13) as the Ottoman conquest of the area loomed large in my mind, even from the comfortable seat of an air-conditioned overland bus (Figure 13).

Figures 11 and 12: Selim Caravanserai, Armenia (P. Blessing)

Figure 13: Neretva river valley approaching Mostar, Bosnia (P. Blessing)

The study of Islamic art, however, also comes with the limits of Middle East politics, and this was a reality both as I wrote my application for the fellowship and when I finally mapped out my itinerary before starting my journal. While writing my application, the on-going war in Syria had long removed this country as a destination, and I regretted not being able to re-visit sites that I had seen in 2005 and 2006, before beginning my PhD studies at Princeton. Sites in southeastern Turkey, on the other hand, were part of my plan. At the time of application, in summer and early fall 2014, the peace process between the Turkish government and Kurdish movements was in full progress, and visiting Mardin, Doğubayezit, and booming Diyarbakır was high up on my agenda. Less than two years later, large parts of the historical Sur district of Diyarbakır lie in ruins after a months-long curfew and military violence. Nothing remains of the hopeful tone of a New Yorker article on restored Armenian churches in Diyarbakir, published in January 2015. Repeated suicide bombings in Ankara, Bursa, and Istanbul have put Turkey on the map of global terror, and travel warnings have mounted for a country with a large, and now struggling, tourism industry. Similar observations are true for Egypt and Tunisia; the latter country was on my initial itinerary, but I decided against going following attacks specifically targeting tourists in fall 2015. The time freed up by this change was put to good use with trips to Armenia and Israel, yet it is still sad that geo-politics are at the base of such decisions. And strangely, all of a sudden Jerusalem felt safer than Istanbul; not that it is, statistically, but something about the energy of the place was profoundly touching. And so I end with one of my favorite photographs of the Dome of the Rock (Figure 14) and deeply grateful for the time I was able to spend exploring the world during my fellowship year.

Figure 14: Dome of the Rock (P. Blessing)

From the latter point of view, the Brooks Fellowship came at a crucial time in my career. It allowed me to develop new ideas for my research projects, to gather materials for teaching, but also to see monuments and cities that I had not been previously able to visit. As I wrote in my blog post in June, Jerusalem is one such example—a city that has played a central role in my studies since my first art history class as an undergraduate, but that was never before on my travel schedule. Similarly, Split, Sarajevo, Dubrovnik (blame Game of Thrones for that last one) are cities that I would have loved to see, without having a chance to do so because they are not part of my research portfolio, and hence not destinations that I could find funding for, or justify the expense of personal funds. In terms of advancing my research, I was able to add sites to my project on fifteenth-century Ottoman architecture while in Turkey, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedonia. Museum research for my ongoing book project on the materiality of architecture in medieval Spain was also part of this year, especially as being based in Europe allowed me to visit collections without the major logistics involved in cross-Atlantic travel. In addition to these more targeted visits, materials gathered in my scrap-books and notebooks will be previous resources as I return to the United States and will continue to process much of what I experienced (Figures 1–4).

Figures 1–4: random pages from one of my scrap-books.

As I prepare the course that I will teach as visiting assistant professor of medieval Mediterranean art history at Pomona College next academic year, the pedagogical uses of my travels become clear. I will be able to include photographs from nearly all the sites I visited in course that cover medieval art and architecture in southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Again Jerusalem will be important, but also Istanbul, Bursa, Marrakesh, Fes, Ravenna, Rome, Malaga, Granada and Cordoba—along with Cairo, Damascus, Samarqand and other major cities in the Mediterranean and the Islamic world. Spending more time in Istanbul—the longest period of time I have been able to remain in the city since my dissertation research—allowed me to revisit many sites and to discover new ones. On the one hand, I was able to photograph buildings such as the Mahmud Pasha Hamam (Figures 5 and 6), built soon after the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul by one of Mehmed the Conqueror’s grand-viziers, or the seventeenth-century Valide Han (Figure 7). Both buildings are part of the maze of streets, full of historical entrepots and other monuments that developed around the Grand Bazar.

Figures 5 and 6: Mahmud Pasha Hamam, Istanbul (P. Blessing)

Figure 7: Courtyard of Büyük Valide Han, Istanbul (P. Blessing)

Similarly, museums that I was able to visit will play a central role in my research and teaching. Some collections, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the David Collection in Copenhagen, and the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid (Figures 8 and 9) have objects that are crucial for my second book, Monuments of Malleability: Illusion, Allusion, and Artifice in Islamic Architecture. At the same time, I was also able to see the collections of Islamic art in several museums, some of which are described in my December post, including several new installations that were opened in the last few years. This was a useful exercise in reflecting about Islamic art as a field of study, its public presentation in a museum setting, but also ways of introducing students to this subject in the classroom. The final result will only become apparent as I redesign my undergraduate survey lecture course on Islamic art in spring 2017, but I can anticipate how the narratives introduced in several museums will have an impact on my teaching. Out of other exhibitions that I saw, Fabric of India at the Victoria and Albert Museum was my favorite with its exhibits ranging from artifacts and videos related to textile production, to historical textiles and the work of contemporary Indian designers. I also enjoyed visiting collections that are not directly related to my research, such as the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen (Figure 10).

Figures 8 and 9: Instituto Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid (P. Blessing)

Figure 10: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark (P. Blessing)

Traveling in this day and age depends of course—sadly to some extent—largely on airplanes, I tried to use overland travel as much as possible. This worked well for my Italy and Balkans trip that involved trains (thanks to the excellent website The Man In Seat Sixty-One), ferries and buses. I was also able to use trains in Morocco, France, Germany, Spain, the UK, and Israel. This was not always the fastest way, but allowed me to see landscapes that I would have missed from the plane, apart from removing the stress of airport security. Still, many of the movements between countries happen in the air, showing both the ugliness of urban development on the coastal section of Beirut, and the beauty of the Alps on a flight between Zurich and Munich on the way to Washington, D.C., for the College Art Association Conference. Landscapes that fascinated me on the way ranged widely. Up front was certainly the Caucasian terrain vague on a mountain pass on the way to Lake Sevan in Armenia, where the fourteenth-century Selim Caravanserai gives reason to pause as to how one would possibly get up here with a medieval trade caravan (Figures 11 and 12). The drive from Sarajevo to Mostar was another memorable landscape (Figure 13) as the Ottoman conquest of the area loomed large in my mind, even from the comfortable seat of an air-conditioned overland bus (Figure 13).

Figures 11 and 12: Selim Caravanserai, Armenia (P. Blessing)

Figure 13: Neretva river valley approaching Mostar, Bosnia (P. Blessing)

The study of Islamic art, however, also comes with the limits of Middle East politics, and this was a reality both as I wrote my application for the fellowship and when I finally mapped out my itinerary before starting my journal. While writing my application, the on-going war in Syria had long removed this country as a destination, and I regretted not being able to re-visit sites that I had seen in 2005 and 2006, before beginning my PhD studies at Princeton. Sites in southeastern Turkey, on the other hand, were part of my plan. At the time of application, in summer and early fall 2014, the peace process between the Turkish government and Kurdish movements was in full progress, and visiting Mardin, Doğubayezit, and booming Diyarbakır was high up on my agenda. Less than two years later, large parts of the historical Sur district of Diyarbakır lie in ruins after a months-long curfew and military violence. Nothing remains of the hopeful tone of a New Yorker article on restored Armenian churches in Diyarbakir, published in January 2015. Repeated suicide bombings in Ankara, Bursa, and Istanbul have put Turkey on the map of global terror, and travel warnings have mounted for a country with a large, and now struggling, tourism industry. Similar observations are true for Egypt and Tunisia; the latter country was on my initial itinerary, but I decided against going following attacks specifically targeting tourists in fall 2015. The time freed up by this change was put to good use with trips to Armenia and Israel, yet it is still sad that geo-politics are at the base of such decisions. And strangely, all of a sudden Jerusalem felt safer than Istanbul; not that it is, statistically, but something about the energy of the place was profoundly touching. And so I end with one of my favorite photographs of the Dome of the Rock (Figure 14) and deeply grateful for the time I was able to spend exploring the world during my fellowship year.

Figure 14: Dome of the Rock (P. Blessing)

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top