-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

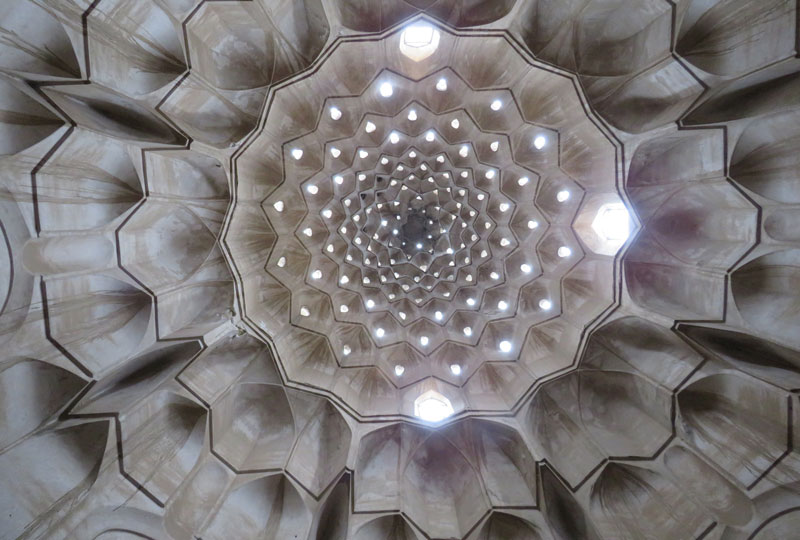

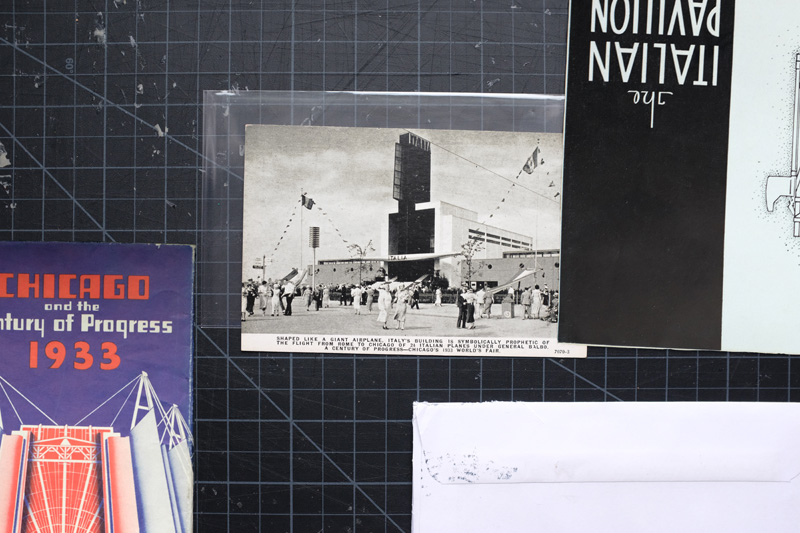

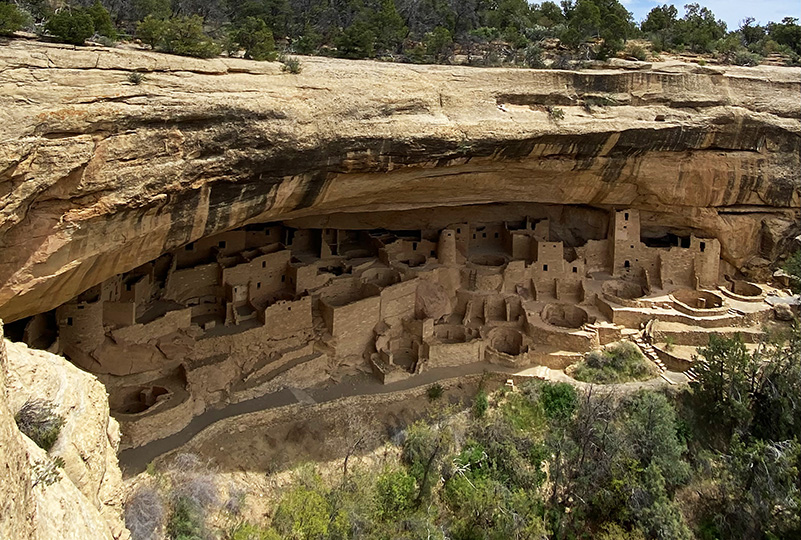

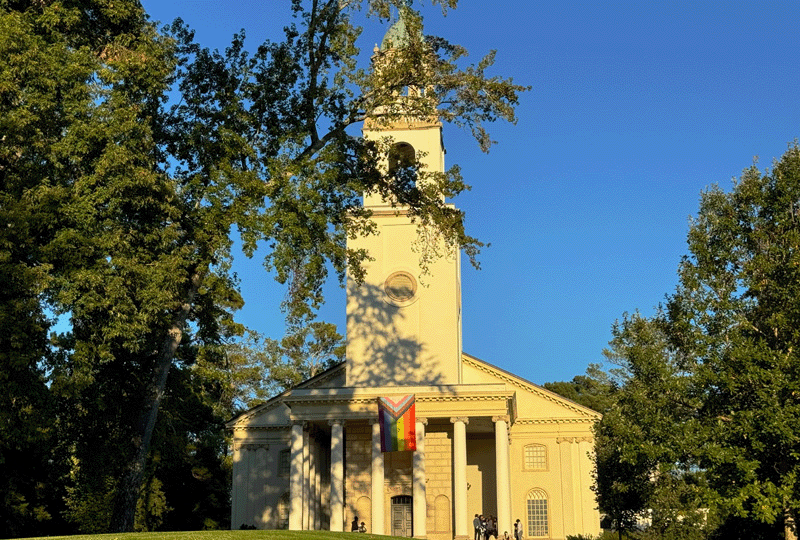

The prestigious H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship allows a recent graduate or emerging scholar to study by travel for one year while observing, reading, writing, or sketching. Fellowship recipients are required to document their travels through monthly posts on the SAH Blog.

2025 Amalie Elfallah

2025 Francesca Sisci

2024 Michele Tenzon

2024 Stathis G. Yeros

2023 Jasper Ludewig

2023 Annie Schentag

2022 Anne Delano Steinert

2022 Adil Mansure

2019 Sundus Al-Bayati

2018 Aymar Mariño-Maza

2018 Zachary J. Violette

2017 Sarah Rovang

2016 Adeyemi Akande

2015 Danielle S. Willkens

2014 Patricia Blessing

2013 Amber N. Wiley

-800x540.jpg?sfvrsn=ec862c9b_2)